Translate this page into:

Watering flowers in the rain: The elusive nature of executive dysfunction in HIV

Address for correspondence: Dr. Kathy Lawler, Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce Street, 3 West Gates Building, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA. E-mail: Kathy.lawler@uphs.upenn.edu

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) frequently experience both neurocognitive and psychiatric dysfunction. Apathy is a prominent neuropsychiatric symptom associated with HIV and is related to neurologic dysfunction. In contrast, depression is independent of neurocognitive impairment in HIV. This case report illustrates the importance of behavioral observations from family members of HIV-positive (HIV+) individuals as a valuable source of information. These behavioral observations can be particularly important in rural resource-limited settings, where cognitive testing is often limited to standardized mental status examinations.

Keywords

Apathy

behavior

depression

HIV

impairment

neurocognitive

Introduction

It is well documented that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enters the central nervous system early after infection and may result in decrements of cognitive, behavioral, and motor performance. Neurocognitive impairment occurs in approximately 30 to 50% of asymptomatic individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).[1] Even mild cognitive impairment is associated with difficulty taking medications and reduced vocational functioning.[2] The specific pattern of neuropsychological deficits associated with HIV involves multiple cognitive domains, including processing speed, learning/memory, psychomotor skills, attention/working memory, and executive function. These cognitive deficits are attributed to damage to the frontostriatal circuitry.[34] HIV-positive (HIV+) individuals with executive dysfunction often display a flat affect and apathy caused by damage to this region of the brain. It is important to differentiate behavior and affective changes associated with HIV because apathy, but not depression, is associated with cognitive dysfunction.[56] Thus, apathy among HIV-infected individuals may reflect HIV-associated neurologic dysfunction, which is not amenable to treatment with antidepressant medications. This may seem a minor problem, since antidepressants are usually not harmful from a medical perspective; however, from a resource perspective, this can be wasteful, with some HIV+ individuals being prescribed expensive medications without benefit.

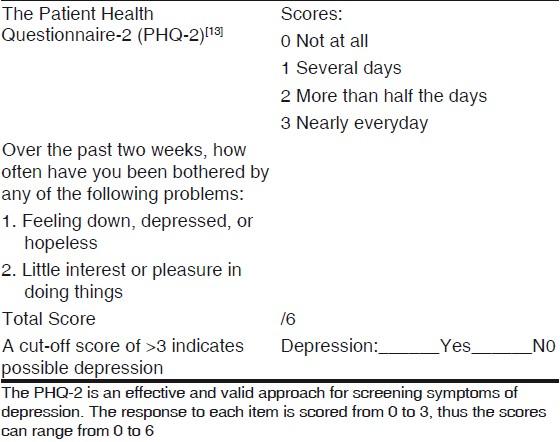

Cognitive impairment and depression often coexist in HIV.[7] Depression does not affect neuropsychological function in HIV-infected individuals,[8] but it can impact quality of life and adversely impact medication adherence.[910] Previous research has shown that a single question about depressed mood has a sensitivity of 85 to 90% for major depression,[11] and adding a second question about anhedonia increases the sensitivity to 95%.[12] Two screening questions from a focused interviewing guide, the Mood Module of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, can help to elicit symptoms of depression.[13] This shortened screening instrument, The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), was designed for use by healthcare workers without formal training in psychiatry, takes only a few minutes (<5 minutes) to administer and score, can be easily interpreted, and has been translated into multiple languages. It is particularly appealing for use in busy, understaffed clinics in rural settings.

Executive functions can be difficult to measure, even with sophisticated neuropsychological tests. Poor insight is often a component of executive dysfunction, so directly asking patients if they are experiencing cognitive problems may be misleading. It is important to obtain information from family/friends who are familiar with the patient's behavior. A cross-cultural investigation demonstrated that executive dysfunction is relatively robust to cultural differences. And the willingness of the family members to report such symptoms did not differ between cultures, which suggest that the construct of the dysexecutive syndrome has validity across cultures.[14]

Case Report

A 42-year-old HIV+ man presented for neuropsychological testing because of unusual behavior observed by his family over the past 3 to 4 years, which included decreased social awareness, occasional inappropriate comments, and “odd” behaviors. According to the family, these behaviors had gradually worsened, and most recently, he was observed “watering flowers in the rain.” The patient himself appeared apathetic and did not understand his family's concern or why they thought his behavior was strange. He was employed full-time as a church pastor, but had recently been asked to take a medical leave due to concerns about his unusual behavior. Consistent with his apathetic demeanor, he had little reaction to this major change in his vocational status. There was no significant medical or psychiatric history prior to the HIV diagnosis. Since his diagnosis with HIV 7 years previously, he had been successfully treated with HAART, with no history of opportunistic infections.

Biomarkers were consistently within normal limits, including CD4 cell counts and an undetectable viral load (<50). At the time of testing, he was fully oriented and denied cognitive or emotional problems. Speech was fluent, and the patient demonstrated an excellent vocabulary consistent with his postgraduate education. Affect was noticeably flat, he appeared unconcerned and apathetic, and initiation was poor. Based on these changes in affect , he had been diagnosed 3 years previously with depression and prescribed antidepressant medication. There was no improvement in his thinking or affect with the antidepressant medication, so it was discontinued 6 months prior to neuropsychological assessment.

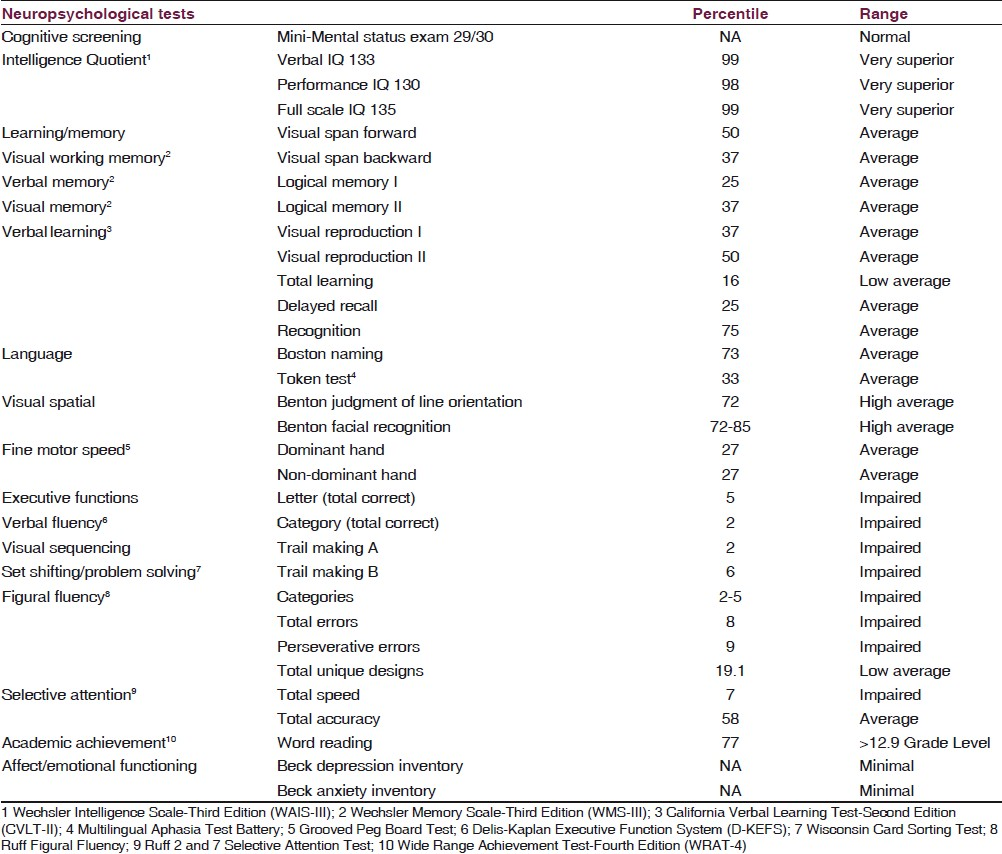

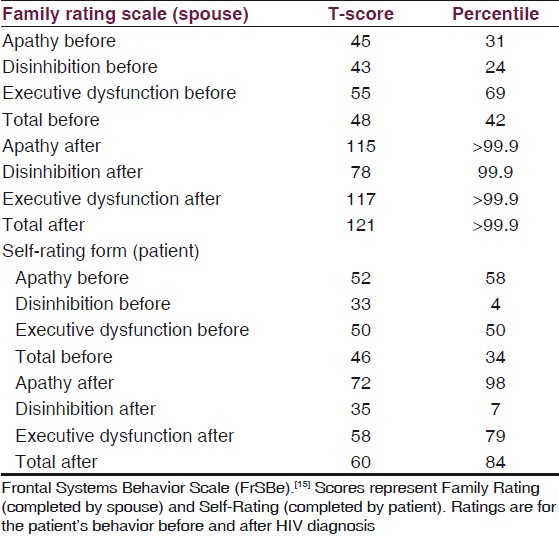

The patient was cooperative throughout several hours of standardized neuropsychological testing. Testing revealed exceptionally high Intelligence Quotient (IQ) scores (Very Superior range) and intact performance on tests of language, attention/working memory, visuospatial perception, and constructional skills. Learning and memory scores were in the average range for the patient's age and education level, which were considered relative impairments in comparison with his high IQ scores. He was slow on a measure of sustained attention and executive dysfunction was evident on tests of visual sequencing, verbal and figural fluency, and problem solving/set shifting [Table 1]. In addition, a structured behavior rating scale revealed an increase in executive dysfunction since diagnosis with HIV [Table 2]. A self-report measure of depression did not confirm the diagnosis of depression. The patient's flat affect, apathy, and poor initiation were attributed to executive dysfunction rather than depression.

Discussion

Since formal neuropsychological testing is often not feasible for individuals infected with HIV in rural settings, this case demonstrates the value of interviewing family members about changes in behavior. Apathy has been associated with cognitive impairment in HIV, specifically executive dysfunction. Thus, family observations may be important in making predictions about performance on executive tasks and by extension, in everyday situations. Recent guidelines[16] support the use of standardized mental status examinations, such as the International HIV Dementia Scale[17] to diagnose HAND in regions where neuropsychological testing is not available. Although not a replacement for cognitive testing, information from family can provide important supplemental information. It takes only a few minutes to ask family members questions targeted at a range of problems commonly associated with executive dysfunction, such as planning problems, lack of insight, apathy and lack of drive, shallowing of affective responses, motivational changes, and lack of concern. This information, combined with two screening questions about depressed mood and anhedonia, may help to distinguish depression from apathy among individuals with HIV. As a first step to screen for depression, the PHQ-2 has demonstrated validity[13] [Table 3]. In a study that screened for depression in 580 patients in a primary care setting, a cut-off score of >3 on the PHQ-2 had a sensitivity of 82.9 and specificity of 90.0.[13] Differentiation of apathy due to executive dysfunction from depression is of great importance, not only clinically, but also to ensure judicious allocation of scarce medical resources. Since cognitive and psychiatric symptoms associated with HIV may vary over time, serial monitoring is recommended.[18]

We are grateful for the valuable suggestions of two anonymous reviewers.

Source of Support: Penn Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI 045008)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Prediction of incident neurocognitive impairment by plasma HIV RNMS and CD4 level early after seroconversion. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1406-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. JINS. 2004;10:317-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationships between cognition and structural neuroimaging findings in adults with human immunodeficiency virus type-1. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;26:353-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caudate Cerebral Blood Flow and Volume are Reduced in HIV Neurocognitively Impaired Patients. Neurology. 2006;66:862-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Apathy correlates with cognitive function but not CD4 status in patients with human immunodeficiency visus. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:114-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between psychiatric status and frontal-subcortical systems in HIV-infected individuals. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:549-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two-year prospective study of major depressive disorder in HIV-infected men. J of Affective Disorders. 2008;108:225-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- HNRC Group.Incident major depression does not affect neuropsychological functioning in HIV-infected men. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV, AIDS and Behav. . 2006;10:253-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indicators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy treatment among HIV/AIDS patients in 5 African countries. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2010;9:98-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case-finding for depression improves patient outcomes: Results from a randomized trial in primary care. Am J Med. 1999;106:36-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case-finding instruments for depression.Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- The application of “dysexecutive syndrome” measures across cultures: Performance and checklist assessment in neurologically health and traumatically brain-injured Hong Kong Chinese volunteers. JINS. 2000;8:771-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe): Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources 2001

- [Google Scholar]

- Updated research nosology for HIVassociated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- The international HIV dementia scale: A new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA), Recognition and Management of HIV-Related Neuropsychiatric Findings and Associated Impairments: Position Statement. 1998. Available from: http://www.psych.org/Resources/OfficeofHIVPsychiatry/Resources/HIVMentalHealthTreatmentIssues_1.aspx

- [Google Scholar]