Translate this page into:

Venous Air Embolism During Removal of Bony Spur in a Child of Split Cord Malformation

Address for correspondence: Dr. Narender Kaloria, Department of Anaesthesia, 4th Floor, Nehru Hospital, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India. E-mail: naren.keli@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

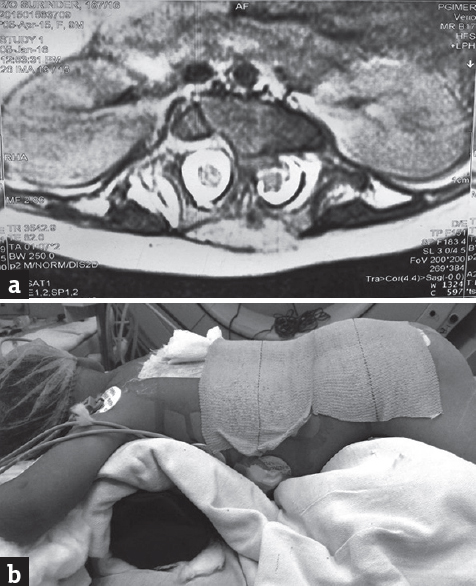

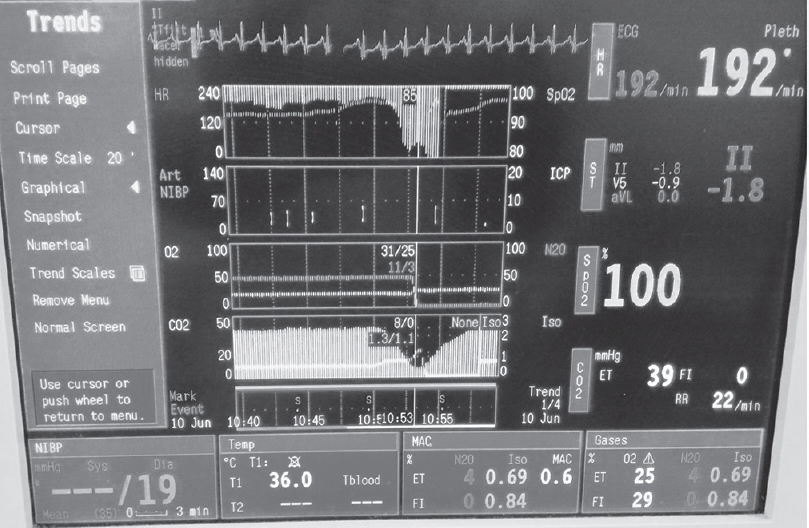

A 1-year-old female child with split cord malformation type 1 with tethered cord was operated for tethered cord release and removal of bony spur [Figure 1a]. The intraoperative monitoring with 5 lead electrocardiogram, SpO2, noninvasive blood pressure, and EtCO2 was used. Standard anesthesia technique was used for induction of anesthesia. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane in nitrous oxide:oxygen mixture (50:50), atracurium, and fentanyl. Ventilation was achieved with pressure control mode to maintain end-tidal CO2 between 35 and 40 mm Hg. The patient was positioned prone on horizontal bolsters [Figure 1b]. As the bony spur was being drilled at its junction with the posterior surface of vertebral body, there was sudden drop in EtCO2 from 40 to 18 mm Hg and then 8 mm Hg. There was bradycardia and loss of pulse oximeter waveform suggestive of electromechanical dissociation. Surgeon was informed about venous air embolism (VAE) and he started flooding the surgical field with a lot of irrigation fluid. N2O was discontinued and 100% O2 was given to the patient. Atropine 0.5 mg was given along with 10 ml normal saline flush, but there was no response in heart rate suggesting loss of circulation. Hence, cardiopulmonary resuscitation in form of chest compression was started in prone position by the surgeon and intravenous fluid was rushed through intravenous line. Soon after initiating cardiac massage, there was an increase in heart rate, SpO2, and EtCO2 [Figure 2]. Rest of surgery and anesthesia were uneventful. In postoperative period, the patient was hemodynamically stable and discharged after 6 days.

- (a) Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging section through the bony spur showing thick bony spur splitting the cord into two halves. (b) Patient is in prone position (bolster below chest and abdomen is free)

- Trends of hemodynamics showing sudden fall in ETCO2 and restore after resuscitation

The VAE is one of the potential serious complications in neurosurgical patients. The incidence of VAE ranges from 16% to 86%, but its incidence was reported lower in pediatric neurosurgical patients than adults.[12] VAE can occur in any neurosurgical procedure, but the incidence of VAE is higher in surgeries that to be done in sitting position and it may also occur in lateral decubitus, prone, and supine position surgeries.[3] In our case, prone position leads to surgical site above the level of heart that created a negative pressure gradient to right atrium and air got sucked in as soon as the bony venous channel got opened during drilling of bony spur at the vertebral body end. The thick bony spur in this case may have led to opening of more osseous venous channel; thus, more air could enter in the circulation. To the best of our knowledge, no such case has been reported in patient with split cord malformation type 1 undergoing tethered cord release where intraosseous air entrapment through bony spur leading to massive VAE and circulatory arrest. Prone position cardiac massage probably led to the breaking of air lock in the heart and return of spontaneous circulation. To conclude, special attention must be paid to detect and manage VAE in patients undergoing surgery for split cord malformation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- The sitting position in neurosurgery: Indications, complications and results. A single institution experience of 600 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013;155:1887-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Venous air embolism during endoscopic strip craniectomy for repair of craniosynostosis in infants. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:340-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- An abrupt reduction in end-tidal carbon-dioxide during neurosurgery is not always due to venous air embolism: A capnograph artefact. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;31:5-7.

- [Google Scholar]