Translate this page into:

Symptom Recognition to Diagnosis: Pathway to Care for Autism in a Tertiary Care Medical Centre

Suravi Patra, MD Department of Psychiatry, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 751019 India patrasuravi@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Objective There is no systematic report on pathway to care in autism from tertiary care medical centers of India. The present study was aimed to evaluate the pathways to care among parents of children with autism-seeking treatment at a tertiary care medical center.

Methods Cross-sectional, observational study involving parents of 38 children with autism spectrum disorder diagnosed with INCLEN diagnostic tool. Pathway to care was assessed using World Health Organization Encounter Form.

Statistical Analysis IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 20.0 was used for analysis; categorical variables were assessed using Chi-square test keeping statistical significance at 0.05%.

Results A total of 74% parents reported going to a general practitioner and 13% reported going to a child psychiatrist as point of first contact. Among them, 71% parents reported seeking care with a child psychiatrist in a tertiary medical center at the fourth point of contact. Also, 84% parents believed in biomedical explanation of autism. Majority of parents sought for speech therapy and medicines for their child with autism which is in tune with their biomedical explanation. Parents were the first to identify developmental concerns, average age of symptom recognition being 2.2 years. Average age of intervention initiation was 40 months, 8 months prior to diagnosis of autism.

Conclusions Early symptom recognition and initiation of interventions is encouraging. Despite having a biomedical explanation of autism and ability to recognize developmental concerns, there is a lag of 4 years in diagnosis and reaching a specialized child psychiatry setup. This lag is a cause of concern owing to the impact on access to evidence-based interventions.

Keywords

autism

pathway to care

India

Introduction

Autism is a group of heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by atypical development of sociocommunicative behaviors and restricted range of interests and activities. Understanding of autism has evolved from Kanner’s syndrome to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM5) spectrum concept encompassing dyad of sociocommunication deficits and restricted repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities.1 Autism remains a behaviorally defined disorder with diagnosis based on standardized structured interview of parents and the affected child with specific focus on socioemotional behavior, language communications, and cognitive development.2

Despite its biological basis and presence of standardized and well-accepted diagnostic criteria, differences in cultural perceptions of normality of development and behavior can influence the diagnosis of autism. Knowledge and beliefs about normal development and any deviance in development and/behavior influence parental recognition of symptoms and help-seeking behavior. Also, professional’s perception of developmental delays influences their ability to identify and diagnose developmental disorders. These cultural and social factors even have an impact on professional’s adherence to international diagnostic criteria for developmental disorders.3

Indian researches from community and hospital settings have documented delay in parental identification of developmental concerns and subsequent delays in help seeking. These delays cause further delays in intervention which adversely affects treatment outcomes. Existing studies have used qualitative methodology and categorically addressed the delays in care seeking3 4; however, pathways to care adopted by parents in the Indian context have never been documented. The sequence of care-giving agencies or organizations, which an affected person contacts, are known to influence diagnosis, management, and outcome.5 Hence, a knowledge of pathway to care in autism would be helpful in formulating solutions at policy level for delivery of mental health services for this population.6

We performed this study to evaluate pathways taken by parents seeking care for autism in a tertiary care medical center in eastern India. We used the World Health Organization Encounter Form to systematically assess the pathways to care.7

Materials and Methods

Study design, setting, and participants: cross sectional observational study performed in child guidance clinic of a tertiary care medical center in east India. Parents of children (age ≤18 years) meeting INCLEN diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, who were willing to participate in the study, were included after taking informed written consent.8 There was no exclusion criteria.

Study Instruments

Semistructured proforma: sociodemographic details of the family were collected using a semistructured proforma prepared for the same.

INCLEN diagnostic criteria for autism: this tool based on DSM IV diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder was indigenously developed and is available free of cost for clinical and research use.8 It has been recommended by the Government of India as a diagnostic instrument and has documented psychometric properties. The tool has two sections, A and B. Section A includes questions and behavioral observation about socialization interaction, communication, and restricted interest and activities. Section B generates a diagnosis of category of autism spectrum disorder.

Childhood autism rating scale (CARS): CARS is a screening, as well as diagnostic, instrument for autism; it also generates a severity score. It includes 14 items addressing different domains of autism and a separate domain on general impression of autism. Scoring is done from 1 to 4; higher score indicating more severe symptoms. Total scores range from 15 to 60 with 30 being the cut-off score for diagnosis of autism. Scores from 30 to 36.5 indicate mild-to-moderate autism, whereas higher scores indicate severe autism.9 The psychometric property of CARS has been well documented in Indian population.10

Encounter Form: details of pathway to care were collected on Encounter Form used in WHO pathway study. This instrument was used by WHO in collecting details about care services used by patients before seeking care in mental health settings. It includes items on profession of each care agency, reason for seeking care, time taken to seek care after symptom recognition, and kinds of interventions offered.

Statistical analysis: data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0, normality was checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov, and categorical data analyzed using Chi-square test. Statistical significance was kept at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval was taken from institute’s ethics committee.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile

Sociodemographic characteristics of our participants are shown in Table 1. Approximately 58% children received diagnosis before 4 years of age. Nine out of 10 children were male and two-thirds were above 6 years of age. More than half of the families belonged to upper socioeconomic status and belonged to urban locality. About two-thirds of the children had a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis and had mild-to-moderate autism scores on CARS.

|

Variable |

n (38) |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CARS, childhood autism rating scale. |

||

|

Age of diagnosis (y) |

||

|

≤4 |

22 |

57.89 |

|

≥5 |

16 |

42.11 |

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

34 |

89.47 |

|

Female |

04 |

10.53 |

|

Religion |

||

|

Hindu |

35 |

92.10 |

|

Muslim |

02 |

5.3 |

|

Christian |

01 |

2.63 |

|

Locality |

||

|

Urban |

20 |

52.63 |

|

Semiurban |

04 |

10.6 |

|

Rural |

14 |

36.84 |

|

Socioeconomic status |

||

|

Upper |

22 |

57.89 |

|

Upper-middle |

15 |

39.47 |

|

Upper-lower |

01 |

02.63 |

|

Diagnosis |

||

|

ASD |

11 |

28.95 |

|

ASD + ADHD |

13 |

34.21 |

|

ASD + ID |

02 |

05.30 |

|

ASD + ID + ADHD |

09 |

23.68 |

|

ASD + seizure disorder + ID |

03 |

07.89 |

|

CARS score |

||

|

Mild–moderate (30–36.5) |

24 |

63.16 |

|

Severe (>36.5) |

14 |

36.84 |

Symptom Recognition

In our sample, parents were the first in noticing symptoms of autism in their children, only two sets of parents reporting that their children’s symptoms were picked up by grandmother and a neighbor. About 40% of the parents noticed language delay as the first symptom of concern, whereas 23% noticed poor eye contact in their child.

Diagnosis was made by psychiatrists in 63% and pediatrician in 8% cases. Neurologists, clinical psychologists, and paraprofessionals like speech language therapists had also made diagnosis in small number of cases. A multitude of interventions were initiated which ranged from pharmacological to nonpharmacological therapies. Parents reported of availing different interventions like speech therapy, occupational therapy, dietary restriction, music therapy, and yoga for their children. Speech therapy was being used by 68% children and medications were used by 60% (Table 2).

|

Category |

n |

% |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Symptom of first concern |

Language delay |

15 |

39.47 |

|

Poor eye contact |

09 |

23.68 |

|

|

Not responding to being called |

03 |

7.89 |

|

|

Abnormal movements/behavior |

03 |

7.89 |

|

|

Stopped speaking |

02 |

5.26 |

|

|

Lack of age appropriate play |

02 |

5.26 |

|

|

Others |

04 |

10.52 |

|

|

Diagnosis made by |

Psychiatrist |

24 |

63.16 |

|

Pediatrician |

08 |

21.05 |

|

|

Neurologist |

02 |

5.26 |

|

|

Clinical psychologist |

02 |

5.26 |

|

|

Paraprofessional (speech/occupational therapist) |

02 |

5.26 |

|

|

Types of interventions |

Speech therapy |

26 |

68.42 |

|

Medicines |

23 |

60.53 |

|

|

Sensory integration |

17 |

44.74 |

|

|

Occupational therapy |

17 |

44.74 |

|

|

Diet restriction |

11 |

28.95 |

|

|

Physiotherapy |

09 |

23.68 |

|

|

Behavior therapy |

05 |

13.16 |

|

|

Music therapy |

05 |

13.16 |

|

|

Yoga |

02 |

05.26 |

Time Delay in Symptom Recognition to Diagnosis

The mean age of symptom recognition in our sample was 2.2 years, intervention was started 8 months before definitive diagnosis of autism was made (Table 3).

|

Event |

Mean age (y) |

Age range |

|---|---|---|

|

Symptom recognition |

2.2 |

3 months–9 years |

|

Intervention |

3.4 |

1–9 years |

|

Diagnosis |

4 |

1.5–9 years |

Pathways to Care

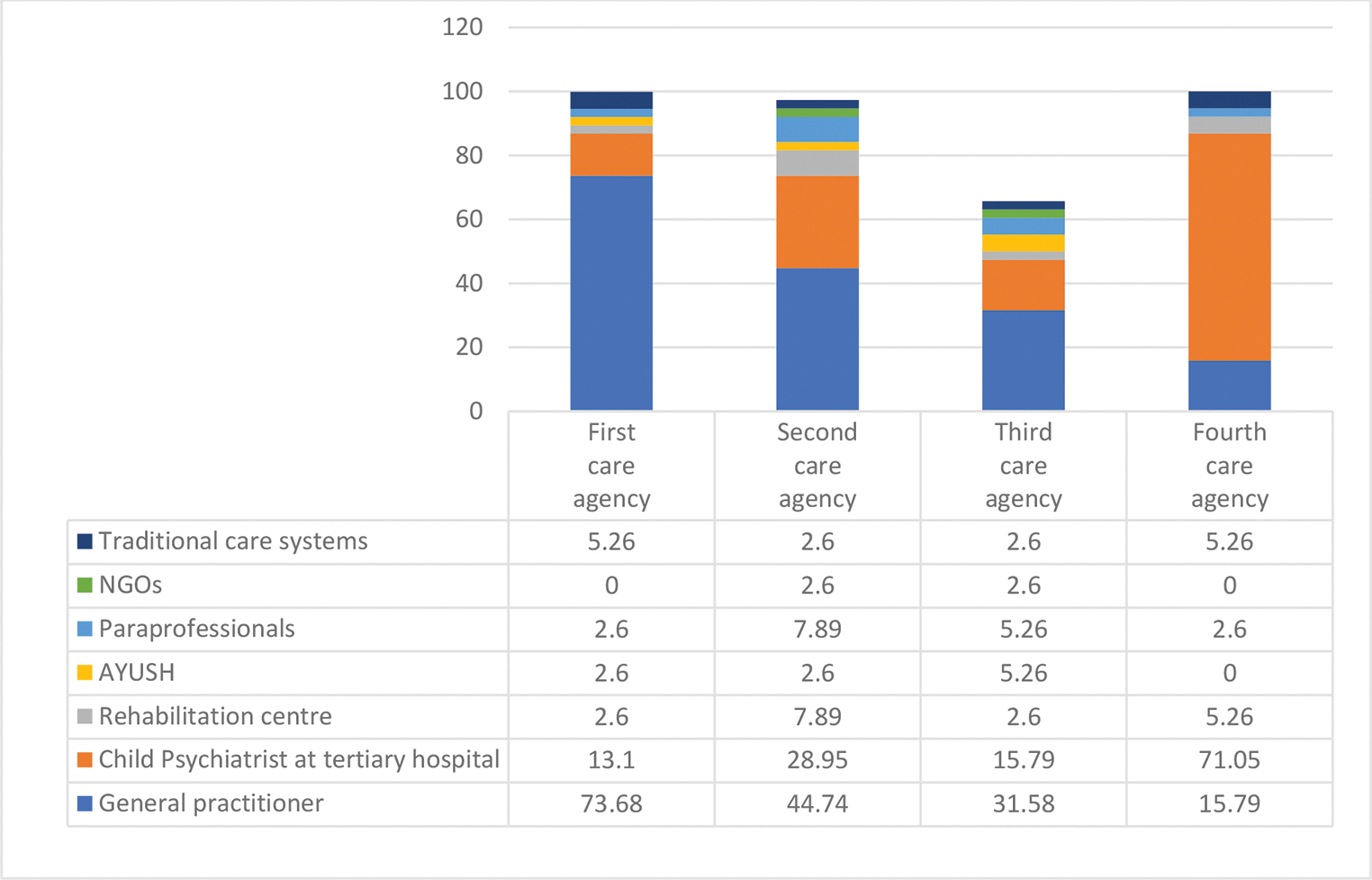

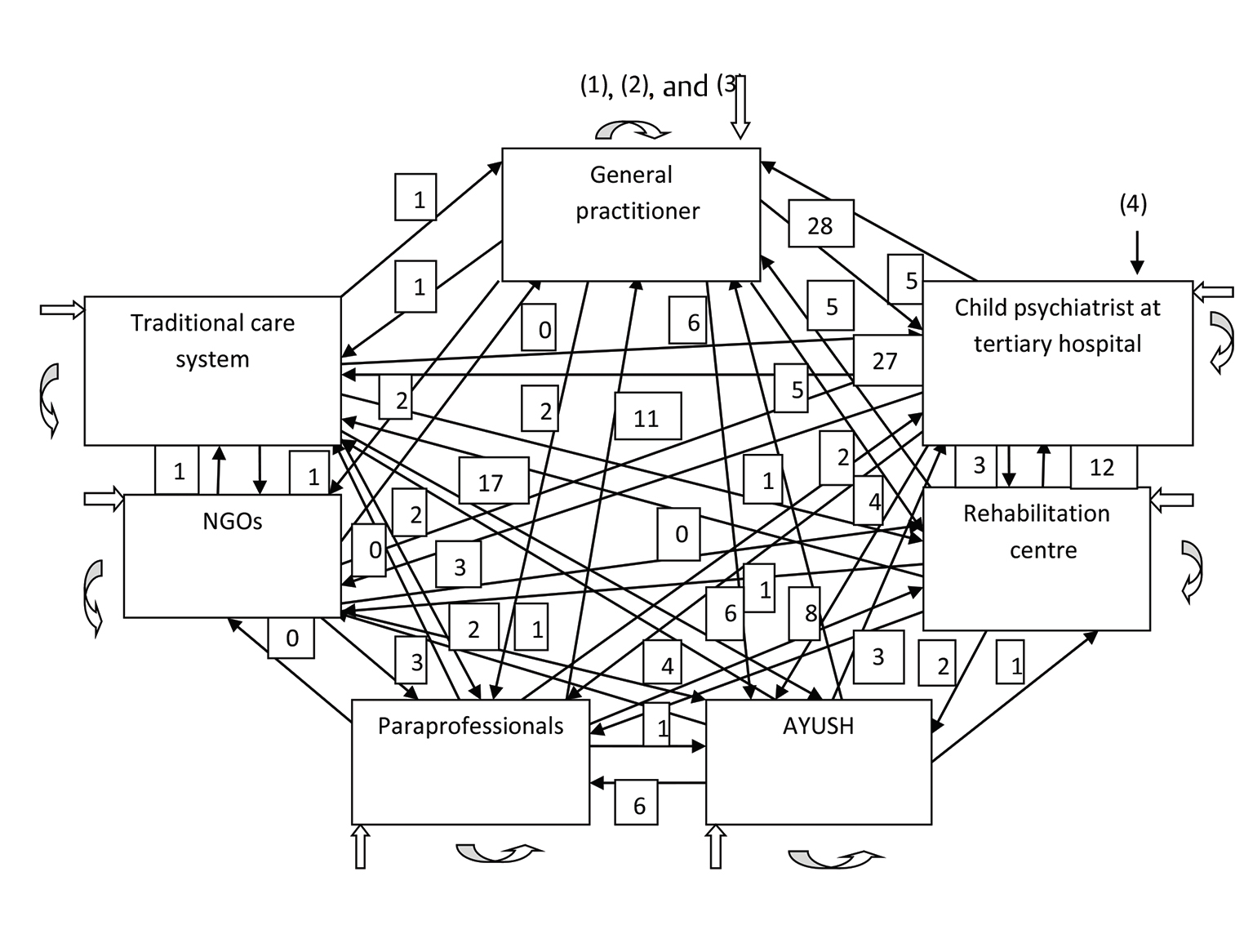

Parents had consulted many care-giving agencies in the process of seeking care for their child with developmental concerns. These ranged from hospitals, clinics, rehabilitation centers, and alternative treatment service providers. General physicians, child psychiatrists, pediatricians, neurologists, paraprofessionals, like speech therapists, physiotherapists, homeopathic practitioners, and faith healers, were all consulted. More than three-fourths of participants’ first point of contact was general practitioners. Seventy-one percent parents approached child psychiatrists in tertiary level institutes at fourth point of contact. Pathways to care adopted by the study participants is depicted in Figs. 1 2.

-

Fig. 1 Pathway to care: points of contact (values shown are in percentages).

Fig. 1 Pathway to care: points of contact (values shown are in percentages).

-

Fig. 2 Pathway to care: autism.

Fig. 2 Pathway to care: autism.

Severity of autism, comorbidity with intellectual disability did not influence care-seeking pathway. However, gender, socioeconomic status, and number of siblings did affect the care-seeking pathway (Table 5). Chi-square test showed significant statistical association of socioeconomic status with choice of first care-giving agency (Fisher’s exact = 60.53, p = 0.017) and choice of second care-giving agency (Fisher’s exact = 97.003, p = 0.046), gender with first care-giving agency (Chi-square = 92.56, p = 0.000) and fourth care-giving agency (Chi-square = 84.5, p = 0.000), number of siblings with first care-giving agency (Chi-square = 103.29, p = 0.000), and fourth care-giving agency (Chi-square = 111.25; p = 0.000; Table 5).

Perceived Cause of Autism by Parents

Most common perceived causes for autism among the parents in our sample were maternal illness, maternal mental state and delivery problems. Faulty parenting, maternal medications intake, and also environmental factors were also perceived to be causative of autism. Karma and bad deeds in past life were considered causal by minority of participants (Table 4).

|

Perceived cause of autism |

n |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Mothers’ mental state during pregnancy |

9 |

23.68 |

|

Maternal illness during pregnancy |

8 |

21.05 |

|

Delivery problems |

8 |

21.05 |

|

Faulty parenting |

7 |

18.42 |

|

Mother’s medicine intake |

5 |

13.16 |

|

Environment |

4 |

10.53 |

|

Bad deeds in past life |

3 |

7.89 |

|

Bad luck |

2 |

5.26 |

|

Genetic |

2 |

5.26 |

|

Karma |

1 |

2.63 |

|

Any other cause |

6 |

15.79 |

Discussion

Autism has a biological basis and behavioral symptoms are consistent across cultures; however, cultural salience to the symptoms varies.11 For a behaviorally defined disorder like autism, knowledge about pathway to care is important for designing policy and establishing systems of care. Recognition of symptoms is often determined by cultural and social factors. Identification of any developmental delay or deviance may be culturally shaped.3 The time duration between symptom recognition and diagnosis has a crucial role in autism, given the impact early intervention has on child outcome.12

This is the first systematically conducted pathway to care study using validated instrument in parents of children with autism from India. The mean age of symptom recognition (2.2 years) in our sample is similar to earlier studies performed in community and hospital settings.3 4 13 The mean age of diagnosis in low- and middle-income (LMIC) countries is 45 to 57 months which is higher than high-income countries.13 Our finding of 48 months as mean age of diagnosis is similar to other Indian research reported elsewhere.3 4 13 In majority of the children, diagnosis was done by psychiatrist which is similar to report from a specialist psychiatry center.4 Diagnosis is often needed for accessing educational and training services in the West; however, this may not be the case in India where services are often provided by a multitude of agencies belonging to the private sector. As there is absence of inclusive education facility in government settings and lack of trained special educators, parents are forced to seek care from private centers where there is no provision for standardization of interventions.14 This could be the reason of initiation of interventions before formal diagnosis of autism.

As in reports from other LMIC countries, language concerns are the first and most common symptom reported from India.3 15 Language delay in our sample was the commonest symptom of first concern. In Indian settings, language delay is often concerned normal, hence might be associated with delayed help seeking. Ability of parents in our sample to recognize language delay might be attributed to improving parental awareness. Parent-led organizations have spearheaded autism movement in India and have contributed in provisioning service delivery also.14 Social problems are the next most commonly reported symptoms of concern.3 Poor eye contact, not responding to being called are deficits in social behavior; since Indian culture is more oriented toward social behavior, parents easily identify these symptoms. In majority of our sample symptoms were identified by parents. Not a single case reported being detected by teachers, as this could be explained by the early onset of symptoms during preschool years.

Commonest explanation of autism in our parent population was maternal mental state, maternal illness during pregnancy, and delivery-related problems. These findings are similar to explanatory models of autism from Bhubaneswar and Kerala. Parents from Kerala had a biomedical explanation to autism which authors attribute to high–health care access.16 17 These findings are contradictory to the supernatural explanation harbored by parents of children with intellectual disability or learning disability.18 These explanations are more biomedical in nature and hence translates into better acceptability of medical interventions.

Our sample did not differ in terms of the choice of care-giving agency as per the presence of comorbidity which is different from that observed in parents seeking care for their children with intellectual disability.18 The difference in care-giving agency choice as per sociodemographic status is also different from studies performed in children with intellectual disability. Severity of autism did not affect care-seeking behavior, whereas gender of the child did which could be due to multiple cultural reasons.

Our study demonstrated that, in our setup, it takes an average four contacts to reach a specialized child psychiatry service. By the time the child reaches a specialized child psychiatrist, valuable time for intervention is lost with understandable dismal impact on outcome. However, it is heartening to see that the mean age of intervention initiation was 3.4 years which was 8 months earlier than receiving a definitive diagnosis. Indian literature has documented that mean age of initiation of intervention is 53 months which is much higher than our center.4 Earlier initiation of intervention in our center could be due to more parental awareness.

Limitations

Our sample might be the subsection of population seeking care at the tertiary care medical center, hence, is not representative of the region. Also, parents seeking care at different agencies might be holding different sets of beliefs which may influence their memory of symptom which the child had in the past. Selective bias in retrospective self-report of symptoms is a known phenomenon, and we acknowledge the limitations of the study caused by this memory bias. Socioeconomic data were based on self-report from participants, with limited objective verification. Longitudinal study from multiple centers is needed to have a broader picture of the phenomenon of care-seeking pathway in Indian context.

Conclusion

Pathway to care in autism shows the crucial link between symptom recognition to treatment seeking. There is a long delay in receiving a diagnosis from the time point of symptom recognition. On an average, four points of contact are needed to reach a specialized child psychiatry center. Though early initiation of interventions is a promising finding in our setup, little can be commented on the quality of these interventions.

|

Variable |

Chi-square/Fisher’s exact value |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|

|

a p < 0.05: the association is statistically significant. b p < 0.01: the association is highly statistically significant. |

||

|

Gender |

||

|

First agency |

92.56 |

0.000b |

|

Fourth agency |

84.5 |

0.000b |

|

Number of siblings |

||

|

First agency |

103.29 |

0.000b |

|

Fourth agency |

111.25 |

0.000b |

|

Socioeconomic status |

||

|

First agency |

60.54 |

0.017a |

|

Second care-giving agency |

97.00 |

0.046a |

|

CARS severity |

||

|

First agency |

6.83 |

0.337 |

|

Fourth agency |

7.62 |

0.471 |

|

Comorbidity with intellectual disability |

||

|

First agency |

2.693 |

0.846 |

|

Fourth agency |

11.11 |

0.268 |

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the parents of children with autism who gave their valuable time for this study.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- From Kanner to DSM-5: autism as an evolving diagnostic concept. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:193-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- From symptom recognition to diagnosis: children with autism in urban India. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(7):1323-1335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lost time-Need for more awareness in early intervention of autism spectrum disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 2017;25:13-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The feasibility and effectiveness of PASS Plus, a lay health worker delivered comprehensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders: pilot RCT in a rural low and middle income country setting. Autism Res. 2019;12(2):328-339.

- [Google Scholar]

- The pathways to psychiatric care: a cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1991;21(3):761-774.

- [Google Scholar]

- INCLEN Study Group. INCLEN diagnostic tool for autism spectrum disorder (INDT-ASD): development and validation. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(5):359-365.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toward objective classification of childhood autism: childhood autism rating scale (CARS) J Autism Dev Disord 1980r;. ;10(1):91-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic accuracy, reliability and validity of childhood autism rating scale in India. World J Pediatr. 2010;6(2):141-147.

- [Google Scholar]

- Examining cross-cultural differences in autism spectrum disorder: a multinational comparison from Greece, Italy, Japan, Poland, and the United States. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;42:70-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early concerns of mothers of children later diagnosed with autism: Implications for early identification. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(1):157-163.

- [Google Scholar]

- Legal provisions, educational services and health care across the lifespan for autism spectrum disorders in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84(1):76-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The status of early identification and early intervention in autism spectrum disorders in lower- and middle-income countries. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(1):30-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Maybe at birth there was an injury”: drivers and implications of caretaker explanatory models of autistic characteristics in Kerala, India. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2015;39(1):62-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parental care-seeking pathway and challenges for autistic spectrum disorders children: A mixed method study from Bhubaneswar, Odisha. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(1):37-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of pathways to care for children with specific learning disability and mental retardation. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014;36(1):27-32.

- [Google Scholar]