Translate this page into:

Supratentorial Pure Cortical Ependymoma: An Unusual Lesion Causing Focal Motor Aware Seizure

Address for correspondence: Dr. K. V. L. Narasinga Rao, Department of Neurosurgery, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore - 560 029, Karnataka, India. E-mail: neuronarsi@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Ependymomas usually arise from the ependymal lining cells of the ventricular system and central canal of the spinal cord. Supratentorial ependymoma is a rare entity with the variable clinical course. In a small number of cases, ependymoma arises from supratentorial parenchyma. Only a few cases are reported in the literature. We report a case of 3-year-old girl with left frontal mass. Total removal of the mass lesion was performed without any neurological deficit. Pathological examination of the excised tumor was consistent with anaplastic ependymoma. We have discussed management strategy of this rare entity.

Keywords

Cortical

ependymoma

extraventricular

pediatric

seizure

INTRODUCTION

Ependymomas are common in the fourth ventricle in children. It constitutes 2%–9% of all intracranial tumors and up to 12% of pediatric brain tumors.[1234]

Less than one-third are found in the supratentorial region.[5] Although it is a kind of lesion derived from the ventricular system, they may occasionally appear outside the ventricular structures, without any relationship of the ventricular system, representing a rare group of ectopic ependymomas (EEs). World Health Organization (WHO) has classified ependymomas into four types: myxopapillary ependymoma, subependymomas, ependymomas, and anaplastic ependymoma (AE).[6] AE has been recognized as WHO Grade III and defined based on their pathological features.[7] Less than thirty cases of EEs were reported, and almost fifteen were purely cortical, and only six cases were anaplastic lesions.[8] We report a rare case of pure cortical ectopic AE.

CASE REPORT

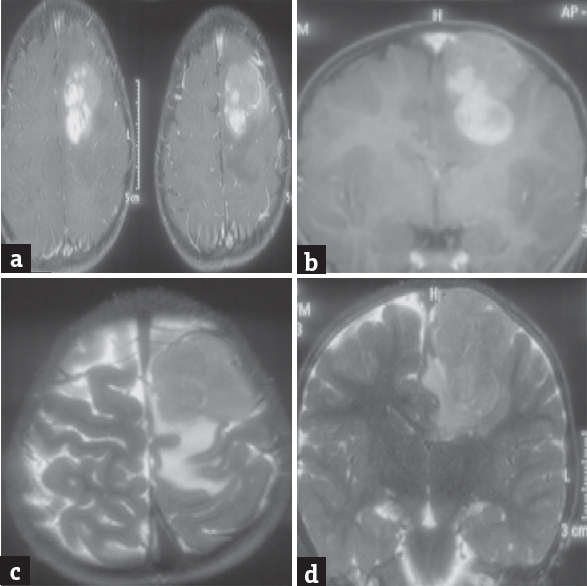

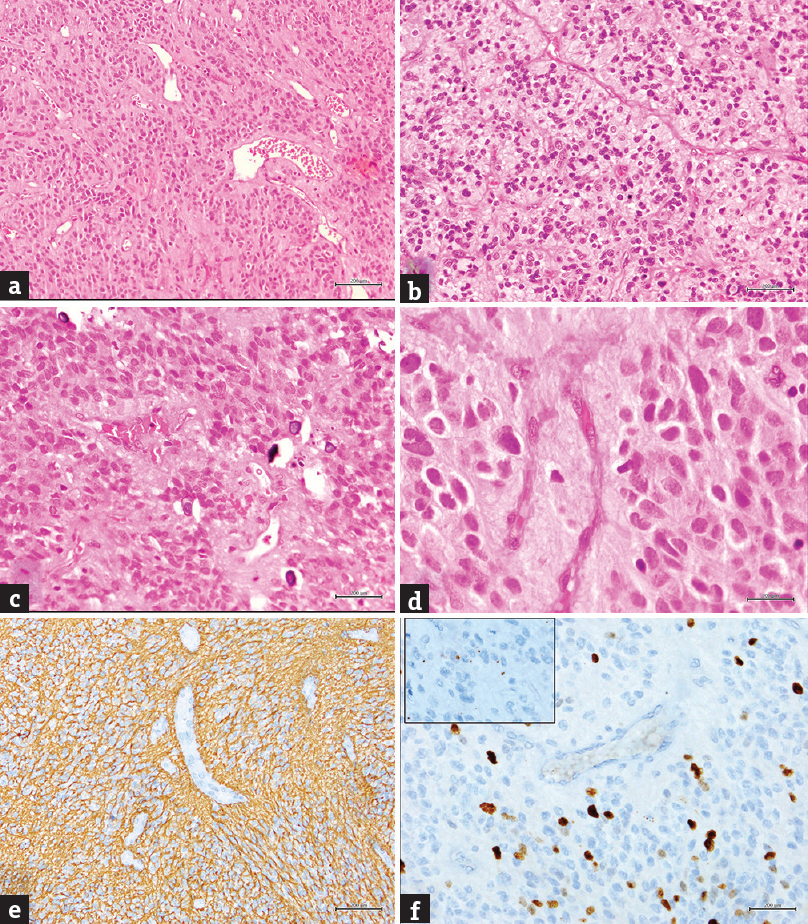

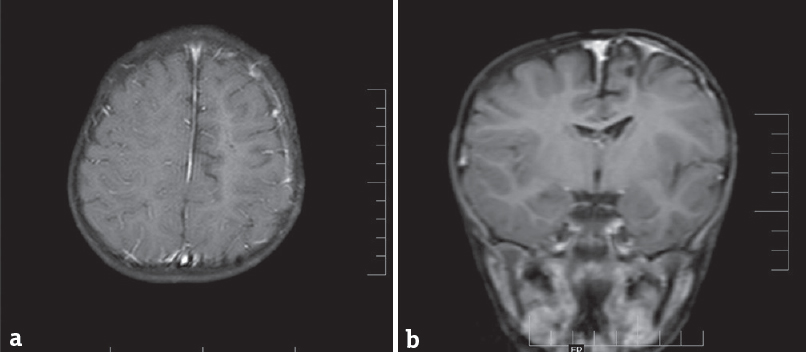

A girl presented to us with a history of episodes of focal right lower limb jerky movements followed by a transient weakness for 3 months. On examination, the child was conscious, obeying without any neurological deficit. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain demonstrated cortical lesion in the left medial frontal region with perilesional edema which is hypointense to isointense on MRI T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images and enhancing on contrast. The lesion was causing mass effect on the ipsilateral lateral ventricle, without any relationship of lateral or third ventricle [Figure 1]. She underwent left frontoparietal craniotomy and gross total decompression of the lesion. The tumor had no connection to the ventricular ependymal lining or the dura. The tumor was heterogeneous with areas which are predominantly firm, with some areas soft in the center, moderately vascular, grayish white, and suckable. Margins were well defined. Near total excision was done using cavitron ultrasonic aspirator. Tissue sent for histopathology of the excised tumor showed glial neoplasm composed of plump spindled cells arranged in lobules with prominent perivascular pseudorosettes; there was increased cellularity with cells exhibiting moderate nuclear pleomorphism and brisk mitosis. The stroma and blood vessels showed calcification. Immunohistochemical findings illustrated that the neoplastic cells were positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein with perivascular accentuation and paranuclear dot positivity for epithelial membrane antigen. The MIB-1 labeling index was high (12%–15%) [Figure 2]. The pathological examination of the excised tumor was consistent with AE (WHO Grade III). The postoperative period was uneventful. Postoperative imaging showed complete excision of the lesion. The child recovered well, and there was no fresh neurological deficit. The child had a favorable outcome after surgery. There is neither any adjuvant chemotherapy nor radiotherapy given considering a gross total resection and her age. At 1-year follow-up, the patient did not have any symptoms and MRI shows no recurrence of the lesion [Figure 3].

- (a and b) Magnetic resonance imaging postcontrast axial and coronal sections showing left medial frontal cortical lesion enhancing on contrast, (c and d) magnetic resonance imaging T2-weighted axial and coronal sections showing isointense to hyperintense cortical lesion in the frontal lobe without any association with ventricles

- (a-d) A cellular glial neoplasm with perivascular rosettes (H and E; a: ×100, b and c: ×200; d: ×400; Note c-in addition shows small specks of calcification, (e) glial fibrillary acidic protein stain showing positive stained neoplastic glial cells with perivascular accentuation (GFAP: ×200), (f) MIB-1 IHC showing significantly increased labeling index (×200); Inset: shows epithelial membrane antigen stain with paranuclear dot positive staining (×400)

- (a and b) Magnetic resonance imaging postcontrast imaging shows no residual lesion at operative site at 1-year follow-up

DISCUSSION

Ependymomas are neuroectodermal tumors arising from the ependymal lining of the cerebral ventricles or the central canal of the spinal cord.[89] The majority of ependymomas in children emerge in the infratentorial region. Supratentorial ependymomas lie mainly in the third or lateral ventricle.[10] Cortical AE (CAE), as in our patient, is extremely infrequent.

Pathogenesis of supratentorial cortical ependymomas is still not fully elucidated.[91112] Sometimes, association with a preexisting lesion like cavernous malformation has given rise to ependymoma due to secretion of angiogenic growth factors.[13] Hegyi et al. reported that glial cells with progenitor properties could be the cell of origin for cortical ependymoma.[14] It is speculated that EEs may arise from fetal rests of ependymal tissue trapped in the developing cerebral hemispheres.[101516] Vernet et al. hypothesized that these ependymomas could result from the disorder of migration which gives rise to an ependymal cyst that can give rise to ependymoma, or these could be primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs) that have differentiated to ependymomas.[17]

Supratentorial ependymomas predominantly involve the brain parenchyma and at presentation usually tend to be larger in size.[18] These tumors present with symptoms of raised intracranial pressure such as a headache and vomiting whereas focal signs as limb weakness and seizures are also common. Van Gompel et al. reported 9 cases of cortical ependymoma, out of which 7 cases had intractable epilepsy.[19] Our case presented with focal motor seizures involving right lower limb.

Differential diagnosis of these tumors includes glioblastoma multiforme, supratentorial PNET, ganglioglioma, and oligodendroglioma.[20] Despite the malignant designation of AE s, they tend to be solid and well demarcated with limited infiltration to the edges of the lesion and conspicuous cleavage from the adjacent normal parenchyma.[21]

On MRI, they do not have any typical findings but usually are isointense to hypointense on unenhanced T1-weighted MRIs and hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI as seen in our case.[20]

Histologically, the tumor cells are characteristically organized in perivascular pseudorosettes. Although ependymomas are moderately cellular tumors with rare mitotic figures (WHO II), our patient had a more aggressive tumor, classified as the WHO Grade III. Less than six ectopic AEs are reported previously in the literature. It is also reported that approximately 15% of AE have a prior diagnosis other than ependymoma, and these tumors were subsequently reclassified as ependymoma, as in our case, which was thought to be PNET initially. The lack of clinical histopathological correlation highlights the need for establishing criteria for classifying these tumors according to their degree of anaplasticity.[22]

A number of prognostic factors for ependymomas have been described in the literature, including patient age, tumor location, histology, and extent of resection.[23] The grade of the tumor and extent of surgical resection have been regarded as important prognostic predictors of survival, so in pediatric population, whenever possible, gross total resection of a tumor should be the goal, as it is the best prognostic factor for good outcome than those with subtotal resection.[81024]

Although total resection is optimal, if vitals structures are involved, then sometimes, it is only possible in approximately 30%–40%.[25] In addition to the extent of resection, proliferative index has been considered as an important prognostic factor,[9] but in some studies, it is not considered as an important prognostic factor.[91626] A highly favorable prognosis is expected after complete tumor resection, which is confirmed by postoperative MRI or computed tomography scan.

The use of postoperative radiotherapy in supratentorial cortical ependymoma cases is still controversial. Some authors have advocated no role of radiotherapy in of low-grade lesions (Grade II) which are completely excised.[1827] However, if the lesion is of high grade (Grade III) or incomplete resection, postoperative radiotherapy is indicated for all lesions.[10] As in our case, the child was 3 year old only and complete excision of the lesion was done; adjuvant radiotherapy was not given.[28] The role of chemotherapy is not well defined for ependymomas,[29] but it may be used in children <3 year old with incomplete excision.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we reported a rare case of 3-year-old girl with CAE. As these are very rare tumors, the diagnosis of these tumors should be kept in mind, and complete excision should be the goal. Adjuvant radiation therapy is not recommended for children in whom complete excision is done.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Posterior fossa ependymomas: Report of 30 cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:659-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival and prognostic factors following radiation therapy and chemotherapy for ependymomas in children: A report of the children's cancer group. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:695-703.

- [Google Scholar]

- The importance of surgery in supratentorial ependymomas.Long-term survival in a series of 23 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16:170-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Revision of the World Health Organization classification of brain tumors for childhood brain tumors. Cancer. 1985;56:1869-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraventricular anaplastic ependymoma with metastasis to scalp and neck. J Neurooncol. 2011;104:599-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial cortical ependymoma in a 21-month-old boy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50:244-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO grade II and III supratentorial hemispheric ependymomas in adults: Case series and review of treatment options. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:323-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of an intracranial ependymoma at the site of a pre-existing cavernous malformation. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:80-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary glial tumor of the retina with features of myxopapillary ependymoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1404-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial lobar anaplastic ependymoma resembling cerebral metastasis: A case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:829-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial extraventricular ependymal neoplasms: A clinicopathologic study of 32 patients. Cancer. 2005;103:2598-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial cortical ependymoma: Report of three cases. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:E192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cortical ependymoma: An unusual epileptogenic lesion. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1187-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cortical anaplastic ependymoma with significant desmoplasia: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:354873.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parasagittal ependymoma resembling falcine meningioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1105-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postoperative radiotherapy for intracranial ependymoma: Analysis of prognostic factors and patterns of failure. J Neurooncol. 2002;56:87-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infratentorial ependymomas in childhood: Prognostic factors and treatment. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:408-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patterns of brain infiltration and secondary structure formation in supratentorial ependymal tumors. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:900-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial ependymomas: Prognostic factors and outcome analysis in a retrospective series of 46 adult patients. Cancer. 2008;113:175-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ectopic cortical anaplastic ependymoma: An unusual case report and literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;124:142-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case report: Primary subcutaneous sacrococcygeal ependymoma: A case report and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:445-7.

- [Google Scholar]