Translate this page into:

Hypothalamic glioma masquerading as craniopharyngioma

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sameer Vyas, Department of Radiodiagnosis and Imaging, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India. E-mail: sameer574@yahoo.co.in

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Hypothalamic glioma account for 10-15% of supratentorial tumors in children. They usually present earlier (first 5 years of age) than craniopharyngioma. Hypothalamic glioma poses a diagnostic dilemma with craniopharyngioma and other hypothalamic region tumors, when they present with atypical clinical or imaging patterns. Neuroimaging modalities especially MRI plays a very important role in scrutinizing the lesions in the hypothalamic region. We report a case of a hypothalamic glioma masquerading as a craniopharyngioma on imaging along with brief review of both the tumors.

Keywords

Craniopharyngioma

glioma

hypothalamus

Introduction

The hypothalamic region may be involved by a large variety of disease processes including tumors, inflammatory, and developmental disorders. The clinical manifestations include vision loss, behavioral changes, and endocrine abnormalities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) play a pivotal role in evaluation of such patients by narrowing the list of differential diagnosis based on the imaging features. However, an accurate diagnosis may not be possible in all cases.

Case Report

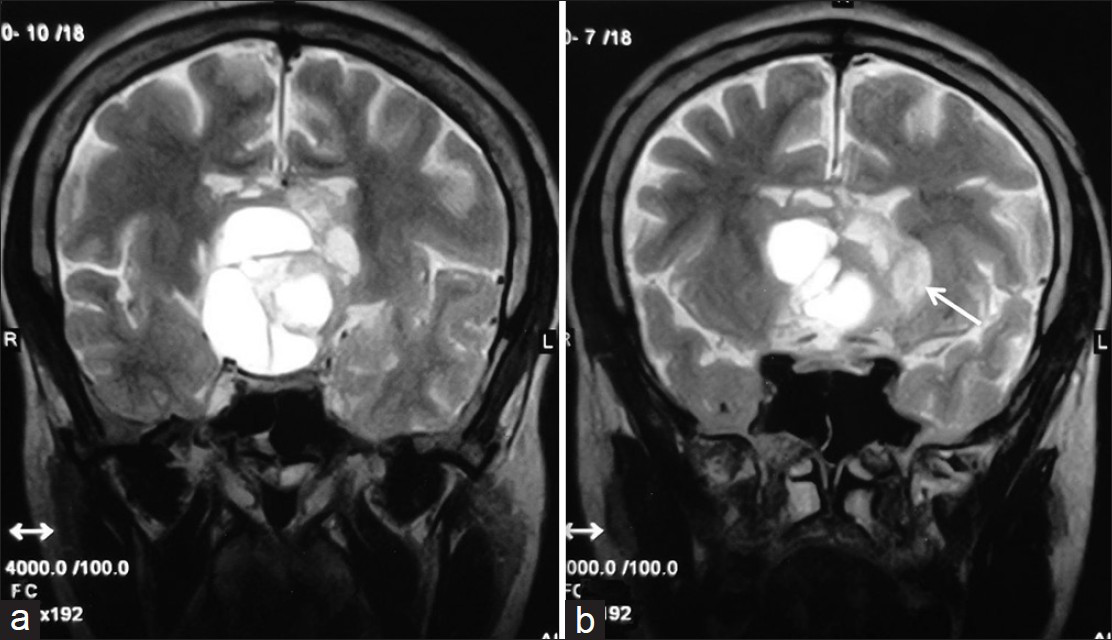

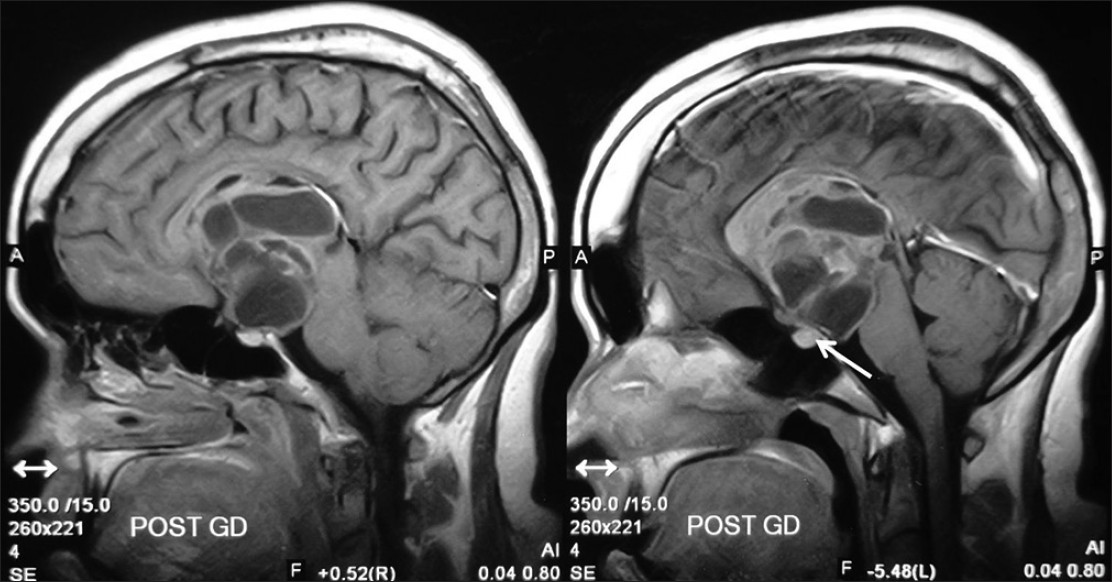

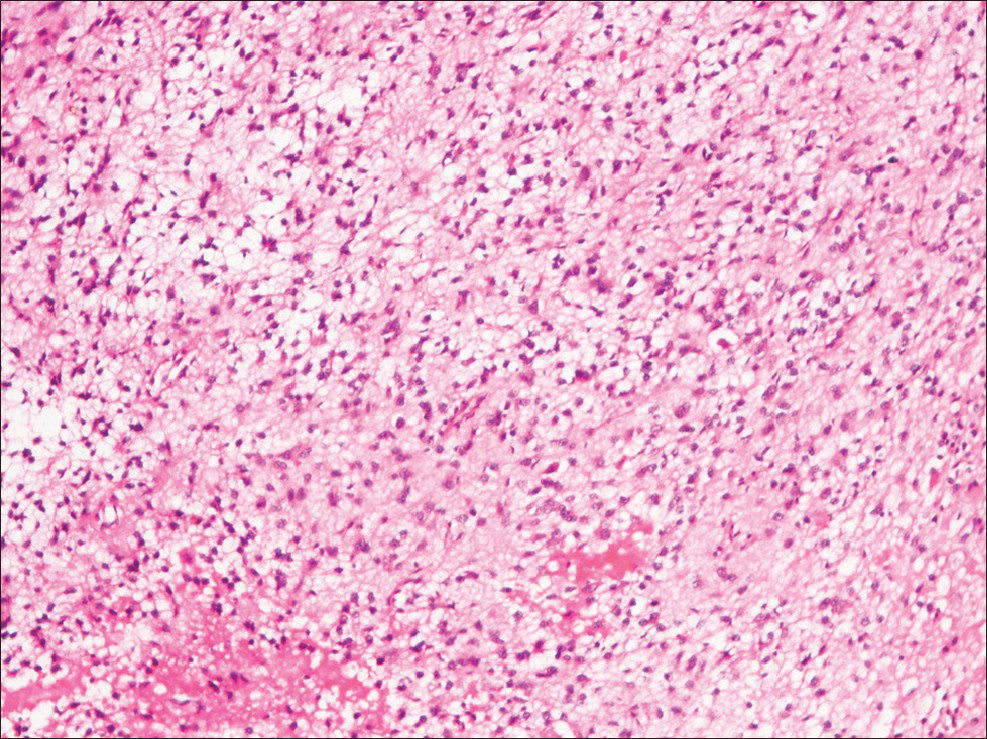

A 25-year-old female patient presented with a history of headache, vomiting, and blurring of vision of 2-month duration. On examination the patient was conscious and cooperative. Visual acuity was 6/18 bilaterally. Fundus was normal. Reduction of the left temporal visual field was seen. Pupils were bilaterally symmetrical and reactive to light. CT and contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain [Figures 1–3] was performed which revealed a solid cystic mass lesion involving the hypothalamus and the thalamus displacing and compressing the third ventricle. Inferiorly the lesion was extending into the interpeduncular cistern. The pituitary stalk and optic chiasm were not visualized separately from the lesion. The pituitary gland was normal in location and signal intensity. The solid component of the lesion showed enhancement on contrast administration. A provisional diagnosis of a suprasellar craniopharyngioma was given. The patient was subsequently operated upon and a right frontoparietal craniotomy with subtotal excision was performed. On histopathology the lesion was diagnosed as a hypothalamic glioma [Figure 4]. Post-surgery the patient developed central diabetes insipidus and is currently E4V4M4 status with left hemiplegia.

- CT (a) and MR (b) axial image showing suprasellar multicystic lesion

- Coronal T2-weighted MR images showing multicystic suprasellar mass lesion, with peripheral small solid component (arrow), which is showing hyperintense signal. The lesion is superiorly compressing the third ventricle extending upto the lateral ventricles. Optic chiasma is not seen separately from the lesion

- Sagittal post-gadolinium T1-weighted MR images showing solid cystic suprasellar mass lesion which is showing peripheral enhancements of the cysts and homogenous enhancement of the solid component. Pituitary gland is seen separately from the lesion (arrow)

- Pilocytic astrocytoma composed of glial cells with small cytoplasmic processes forming loose fibrillary matrix (H and E, ×100)

Discussion

Craniopharyngiomas arise from the remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct.[1] They are the most common nonglial brain tumors in children and account for half of all suprasellar masses in this age group.[2] More than half of craniopharyngiomas occur in children and young adults. Intrasellar craniopharyngiomas are seen in 4% of the cases, 21% are both sellar and suprasellar, and 75% of the cases are limited to the suprasellar region alone, often with extension up into the third ventricle.[3] Histologically craniopharyngioma can be divided into papillary and adamantinomatous subtypes. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma have a bimodal distribution, with the first peak between 5 and 15 years old and a second peak between 45 and 60 years old. The papillary subtype occurs in adults at a mean age of 40-55.[4] Males are more commonly affected.[5] Symptoms include headaches, visual field defects, and hypothalamic dysfunction. Adamantinous craniopharyngioma are usually suprasellar and are predominantly cystic. T1 hyperintense cysts are typical; however, T1 hypointense cysts are also possible. The tumor is mostly lobulated and may encase subarachnoid arterial vessel. Squamous-Papillary variant is spherical in shape, generally intrasellar/suprasellar or suprasellar. It is predominantly solid with hypointense cysts on T1. On CT large cysts with CSF density and soft tissue density enhancing solid component are seen. Calcification is seen in 90% and is stippled and often peripheral in location.

Hypothalamic chiasmatic gliomas, on the other hand, form 10-15% of supratentorial tumors in children. The most common age of presentation is 2-4 years. The patients usually present with loss of visual acuity. Growth hormone dysfunction is seen in 20% of the cases.[1] Hypothalamic gliomas are associated with a family history of neurofibromatosis type 1 in 20-50% of the cases.[1] In such cases the glioma may have a more indolent course and may even regress spontaneously.[67] These gliomas are hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences. Larger tumors tend to be heterogeneous with both cystic and solid components. The solid component shows significant contrast enhancement.[6] A study by Kornreich et al. showed that in non-NF patients, the chiasm and hypothalamus were the most common sites of involvement, the tumor was mass-like, and cystic components were frequently seen, as was extension beyond the optic pathways.[8]

In our case the lesion had both solid and cystic component with enhancement and did not show any calcification; however, the age of the patient was not in favor of a diagnosis of hypothalamic glioma. Bisson et al., have reported two similar cases of OCHGs appearing like craniopharyngiomas on neuroimaging.[9] In another study by Bommakanti et al. nine out of 18 cases with a pre-op diagnosis of optico-chiasmatic-hypothalamic gliomas had mixed solid and cystic component. Of these histological examination revealed craniopharyngioma in two patients.[10]

To conclude, the main differentiating features between craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic glioma are the presence of mixed intensity cysts on T1 and calcification in craniopharyngioma and the relative young age of presentation in hypothalamic gliomas. Yet, it is not always possible to differentiate craniopharyngiomas from hypothalamic glioma. Thus, obtaining a tissue diagnosis via biopsy may be the right course of action in planning further management, whenever diagnosis is in doubt.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Lesions of the Hypo-thalamus: MR imaging diagnostic features. Radio Graphics. 2007;27:1087-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in children. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroimaging of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(Suppl 1):2-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR differentiation of adamantinous and squamous-papillary craniopharyngiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:77-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic resonance analysis of suprasellar tumors of childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1991-1992;17:284-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Initial management of children with hypothalamic and thalamic tumors and the modifying role of neurofibromatosis-1. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;32:154-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optic pathway glioma: Correlation of imaging findings with the presence of neurofibromatosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1963-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypothalamic-opticochiasmatic gliomas mimicking craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39:159-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optic chiasmatic-hypothalamic gliomas tissue diagnosis essential. Neurology. 2010;58:833-40.

- [Google Scholar]