Translate this page into:

Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A 14-month-old male child presented with recurrent generalized seizures, spastic hemiplegia, microcephaly and had developmental delay in motor and speech domains. CT of the brain revealed characteristic features diagnostic of infantile type of cerebral hemiatrophy or Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome.

Keywords

Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome

hemiatrophy

Introduction

Dyke-Davidoff-Masson syndrome (DDMS) refers to atrophy or hypoplasia of one cerebral hemisphere (hemiatrophy), which is usually due to an insult to the developing brain in fetal or early childhood period.[1] The clinical features are variable and depend on the extent of brain injury. More commonly they present with recurrent seizures, facial asymmetry, contralateral hemiplegia, mental retardation or learning disability, and speech and language disorders. Sensory loss and psychiatric manifestations like schizophrenia had been reported rarely.[23] The typical radiological features are cerebral hemiatrophy with ipsilateral compensatory hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses. The syndrome had been documented mainly in adolescents and adults.[4–6] However, it can also be seen in children.[7] We present here a 14-month-old child with typical clinical and imaging features of DDMS.

Case Report

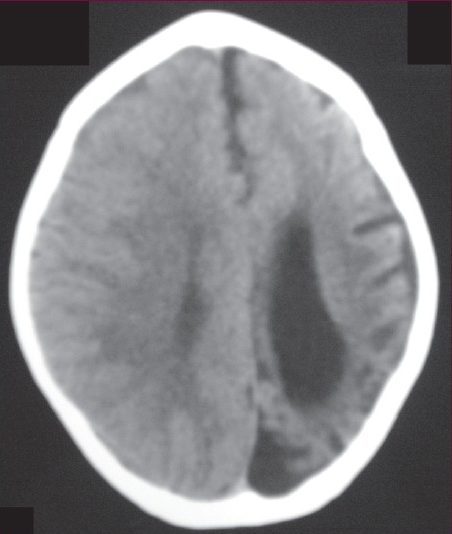

A 14-month-old male child, born full term, to non-consanguineous parents, presented with recurrent generalized seizures for last 4 months. There was no history of significant antenatal or perinatal complications. He had delayed milestones of development in the form of not able to stand or walk and not spoken a word. He had microcephaly (< 3rd centile) without any neurocutaneous marker or facial asymmetry. The bilateral carotid pulsations were normal with no bruit. Vision and hearing were normal, and cranial nerves were intact. Neurological examination revealed right-sided spastic hemiparesis with brisk tendon reflexes and extensor planter response, other systemic examinations being normal. A plain and contrast CT of the brain was done which revealed atrophy of left cerebral hemisphere with dilatation of the ipsilateral ventricle, widening of sulci and sylvian fissure on the same side. There was also shift of midline to left and thickening of calvarium on the left side [Figure 1]. From the above CT findings, a diagnosis of DDMS was made. The child was started on oral Carbamazepine; 10 mg/kg in two divided doses, gradually increased every week till the dose of 30 mg/kg is achieved. He responded well to the drug followed by sessions of physiotherapy. He was seizure free for next 3 months but then unfortunately lost for follow-up.

- Plain CT head showing atrophy of left cerebral hemisphere with dilated ipsilateral lateral ventricle, widening of sulci and atrophy of gyri on the left side. There is also thickening of the calvarium on the left side.

Discussion

In 1933, Dyke, Davidoff and Masson first described the syndrome in plain radiographic and pneumoencephalographic changes in a series of nine patients.[8] It is characterized by asymmetry of cerebral hemispheric growth with atrophy or hypoplasia of one side and midline shift, ipsilateral osseous hypertrophy with hyperpneumatisation of sinuses mainly frontal and mastoid air cells with contralateral paresis.[9] Other features are enlargement of ipsilateral sulci, dilatation of ipsilateral ventricle and cisternal space, decrease in size of ipsilateral cranial fossa, and unilateral thickening of skull. Clinical presentations include variable degree of facial asymmetry, seizures, contralateral hemiparesis, mental retardation, learning disabilities, impaired speech, etc. Seizures can be focal or generalized. Complex partial seizure with secondary generalization also had been reported.[10] Both sexes and any of the hemisphere may be affected, but male gender and left side involvement are more common.[11]

The human brain reaches half of its adult size during the first year of life and three fourth of the adult size is attained by the end of 3 years. The surface of the hemisphere remains smooth and uninterrupted until early in the fourth month of gestation. By the end of the eighth month, all the important sulci can be recognized.[12] The developing brain presses outward on the bony skull table resulting in gradual increase in head size and shape. When the brain fails to grow properly, the other structures grow inward resulting in increased width of diploic spaces, enlarged sinuses, and elevated orbital roof.[13] These changes can occur only when brain damage is sustained before 3 years of age; however, it may become evident as early as 9 months after the injury.[14]

Cerebral hemiatrophy can be of two types, infantile (congenital) and acquired.[15] The infantile variety results from various etiologies such as infections, neonatal or gestational vascular occlusion involving the middle cerebral artery, unilateral cerebral arterial circulation anomalies, and coarctation of the midaortic arch.[1516] The patient becomes symptomatic in the perinatal period or infancy. The main causes of acquired type are trauma, tumor, infection, ischemia, hemorrhage, and prolonged febrile seizure. Age of presentation depends on time of insult and characteristic changes may be seen only in adolescence or adult.

In our case, the findings of left cerebral hemiatrophy with enlarged cortical sulci, microcephaly, and presentation at the age of 14 months reflect an onset of brain insult after the completion of sulci formation, probably of vascular origin involving left middle cerebral artery.

A proper history, thorough clinical examination, and radiologic findings provide the correct diagnosis. This condition is to be differentiated from Basal ganglia germinoma, Sturge Weber syndrome, Silver- Russel syndrome, Linear nevus syndrome, Fishman syndrome, and Rasmussen encephalitis.[1718] Sturge-Weber syndrome (encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis) represents cerebral atrophy associated with leptomengeal angioma. The patients have seizure disorder, mental retardation, and hemiparesis. The distinguishing features are the presence of port-wine facial nevus, intracranial tramtrack calcification, and the absence of midline shift.[19] Basal ganglia germinoma is a rare tumor of the brain, which may present with progressive hemiparesis and cerebral hemiatrophy.[20] Silver-Russel Syndrome is characterized by poor growth, delayed bone age, clinodactyly, normal head circumference, normal intelligence, classical facial phenotype (triangular face, broad forehead, small pointed chin, and thin wide mouth), and hemihypertrophy.[21] Fishman syndrome or encephalocraniocutaneus lipomatosis is a rare neurocutaneus syndrome comprising unilateral cranial lipoma, lipodermoid of eye. The patient may present with seizure and cerebral imaging may show calcified cortex and hemiatrophy.[22] Linear nevus syndrome is characterized by typical facial nevus, mental retardation, recurrent seizures, and unilateral ventricular dilatation resembling cerebral hemiatrophy.[19] Rasmussen encephalitis is a chronic progressive immune mediated disorder thought to be secondary to viral infections. It usually presents with intractable focal epilepsy and cognitive defects in children. The imaging features include unilateral hemispheric atrophy without any calvarial changes.[23]

Patients with DDMS usually present with refractory seizures and the treatment should focus on control of the seizures with suitable anticonvulsants. Sometimes multiple anticonvulsants are in use. Along with drugs, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy play a significant role in long-term management of the child. Prognosis is better if the onset of hemiparesis is after 2 years of age and in absence of prolonged or recurrent seizure.[9] Hemispherectomy is the treatment of choice for children with intractable disabling seizures and hemiplegia with a success rate of 85% in selected cases.[7]

As hemispherectomy is not available even in many urban tertiary care centers, it is very important for a rural neurologist or pediatrician to diagnose the condition early by means of suitable imaging (CT) and the treatment should focus on optimum control of seizures, revision of drug doses from time to time, and domiciliary physiotherapy.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Dyke-Davidoff-Masson Syndrome manifested by seizure in late childhood: A case report. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:367-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment- refractory Schizoaffective disorder in a patient with Dyke-Davidoff Masson Syndrome. CNS Spectr. 2009;14:36-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dyke-Davidoff-Masson Syndrome: Classical imaging findings. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2010;5:124-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral hemiatrophy and homolateral hypertrophy of the skull and sinuses. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1933;57:588-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temporo-spatial analysis define epileptogenic and functional zone in a case of DDMS. Seizure. 2011;20:713-716.

- [Google Scholar]

- Left hemisphere and male sex dominance of cerebral hemiatrophy(DDMS) Clin Imaging. 2004;28:163-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the Nervous system. In: Standring S, ed. Gray's Anatomy (40th ed). London, Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier; 2008. p. :385.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dyke-Davidoff-Masson Syndrome: Five case studies and deductions from dermatoglyphics. Clin Pediatr. 1972;11:288-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coarctation of midaortic arch presenting with monoparesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:210-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Degenerative diseases and hydrocephalus. In: Lee SH, Rao KC, Zimmerman RA, eds. Cranial MRI and CT. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999. p. :212-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal ganglia germinoma with cerebral hemiatrophy. Pediatric Neurology. 1999;20:312-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Encephalocraniocutaneouslipomatosis(Fishman Syndrome): A rare neurocutaneous syndrome. J PediatrChildHealth. 2000;36:603-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen encephalitis: An update. Schweizer Archiv fur Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 2011;162:225-31.

- [Google Scholar]