Translate this page into:

Goniometric Assessment of Muscle Tone of Preterm Infants and Impact of Gestational Age on Its Maturation in Indian Setting

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rajni Farmania, Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 029, India. E-mail: rajni.farmania@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

The normative data on muscle tone of preterm infants by goniometric assessment in Indian setting are scarce.

Aim:

The aim of this study it to provide a normative objective data of muscle tone of preterm infants by gestation using goniometer.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, observational study including preterm infants admitted in a tertiary care hospital from North India.

Subjects and Methods:

The objective dimension of muscle tone assessment of 204 healthy preterm infants was done; 61 infants completed follow-up till 40 weeks’ postconceptional age (PCA) and were compared to term infants.

Statistical Analysis Used:

SPSS (version 16.0) was used. The intergroup comparison was done through ANOVA, and the localization of differences between the groups was determined through multiple comparisons by post hoc test.

Results:

Mean gestational age was 34.3 ± 1.7 weeks. Angles were as follows: adductor = 100.1 ± 8.7, popliteal = 118.9 ± 8.6, dorsiflexion = 39.0 ± 9.0, heel to ear = 121.90 ± 7.90, wrist flexion = 46.0 ± 10.2, and arm recoil = 122.2° ± 16.6°. The evolution of muscle tone as indicated by heel-to-ear angle shows progressive maturation from 32 weeks’ gestation while adductor angle, popliteal angle, and arm recoil mature predominantly after 36 weeks’ gestation. Comparison of preterm infants to term at 40 weeks’ PCA demonstrated significantly less tone in all except posture and heel to ear.

Conclusions:

Goniometric assessment provides a objective normative data of muscle tone for preterm infants. Maturation of heel to ear and posture evolves from 32 weeks onwards and are the earliest neurologic marker to mature in preterm infants independent of the gestational age at birth.

Keywords

Goniometric assessment

muscle tone

neurologic maturation

neurologic maturation

normative data

INTRODUCTION

Preterm infants are always at the risk of various health problems requiring prolonged hospitalization, intensive care admission subjecting to high morbidity and mortality. They are also at risk of developing neurological problems either because of adverse environmental factors, lack of developmental supportive care, poor nutrition, or various health factors.[12] The risk of development of cerebral palsy in those born ≥34 weeks is 1% at 5 years’ age, increasing to 5%–15% in those born <32 weeks.[34] Hence, preterm infants born <35 weeks should be followed up regularly to identify any disability and improve outcome.[5] Birth weight and gestational age play an important role in the prognostication of growth and development of preterm infants as both represent systemic organ structural and functional maturation.[6]

Amiel-Tison has developed a clinical tool for assessment of the neurological status of preterm infants at 40 weeks’ postconceptional age (PCA).[78] This tool takes into account of the clinical signs, which depend on the neuronal integrity of the central nervous system (e.g., active and passive tones in the axis and limbs, behavior and alertness, and spontaneous movements). The interobserver reliability of this tool has been found to be very good. When it is performed by some trained clinical personnel, the results correlate well with the developmental performance at later age (e.g., at 2 years’ corrected age).[91011]

Muscle tone can be assessed by two components, namely, active and passive tone.[67] Factors influencing the muscle tone such as perinatal adverse event, maternal medications during delivery, and acute sickness in newborn affect active tone rather than passive tone to a great extent. Hence, passive tone provides the true assessment of tone of infant which can be measured accurately using goniometer.

Previous reports on neonatal assessment provide numerical values for the full term[1213] and some values for preterm infants;[14] however, the normative data on muscle tone of infants in Indian setting are scarce. This study was planned to provide baseline goniometric angles for the preterm infants from Indian subcontinent and to study impact of gestational age on its maturation.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The study was a prospective longitudinal study of birth cohort of preterm (<37 weeks) and full-term infants (≥37 weeks) conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital of North India. The muscle tone of 204 healthy preterm infants with normal perinatal course was measured within 72 h of life with the help of a goniometer. Assessment of gestational age was done by New Ballard Score.[15] The birth weight in relation to gestational age was classified as per the intrauterine growth chart of Lubchenco.[6] PCA was calculated as gestational age plus days/weeks of extrauterine life. Small for gestational age, presence of congenital anomalies, abnormal neurological examination at term, those delivered by breech, use of mechanical ventilation, and abandonment of study before 40 weeks were excluded from the study. Totally 61 preterm infants completed follow-up till 40 weeks’ PCA. Full-term infants were taken as control group and subjected to single examination within 72 h of life.[16]

Muscle tone was objectively assessed by Amiel-Tison angles using goniometer. The following angles were measured: adductor angle, popliteal angle, dorsiflexion angle, difference in rapid and slow angle, heel-to-ear angle, arm recoil, wrist flexion, scarf sign, and posture (score 0–4). Interpersonal error was avoided as a single person did the measurement of angles in both first and the follow-up assessment.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software (version 16.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc. USA). The intergroup comparison was done through one-way ANOVA; P < 0.05 was considered significant. The localization of differences between the groups was determined through multiple comparisons by post hoc Student–Newman–Keuls.

RESULTS

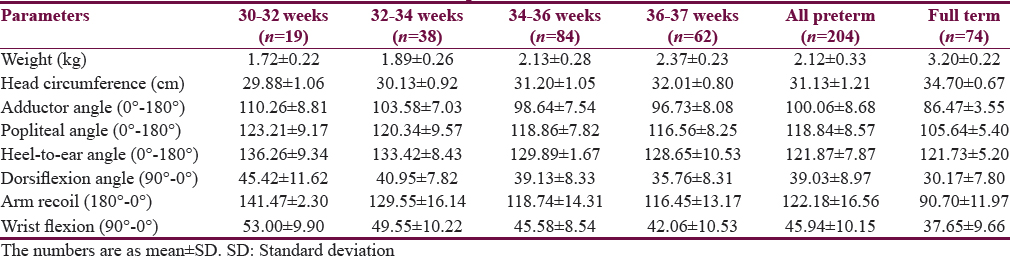

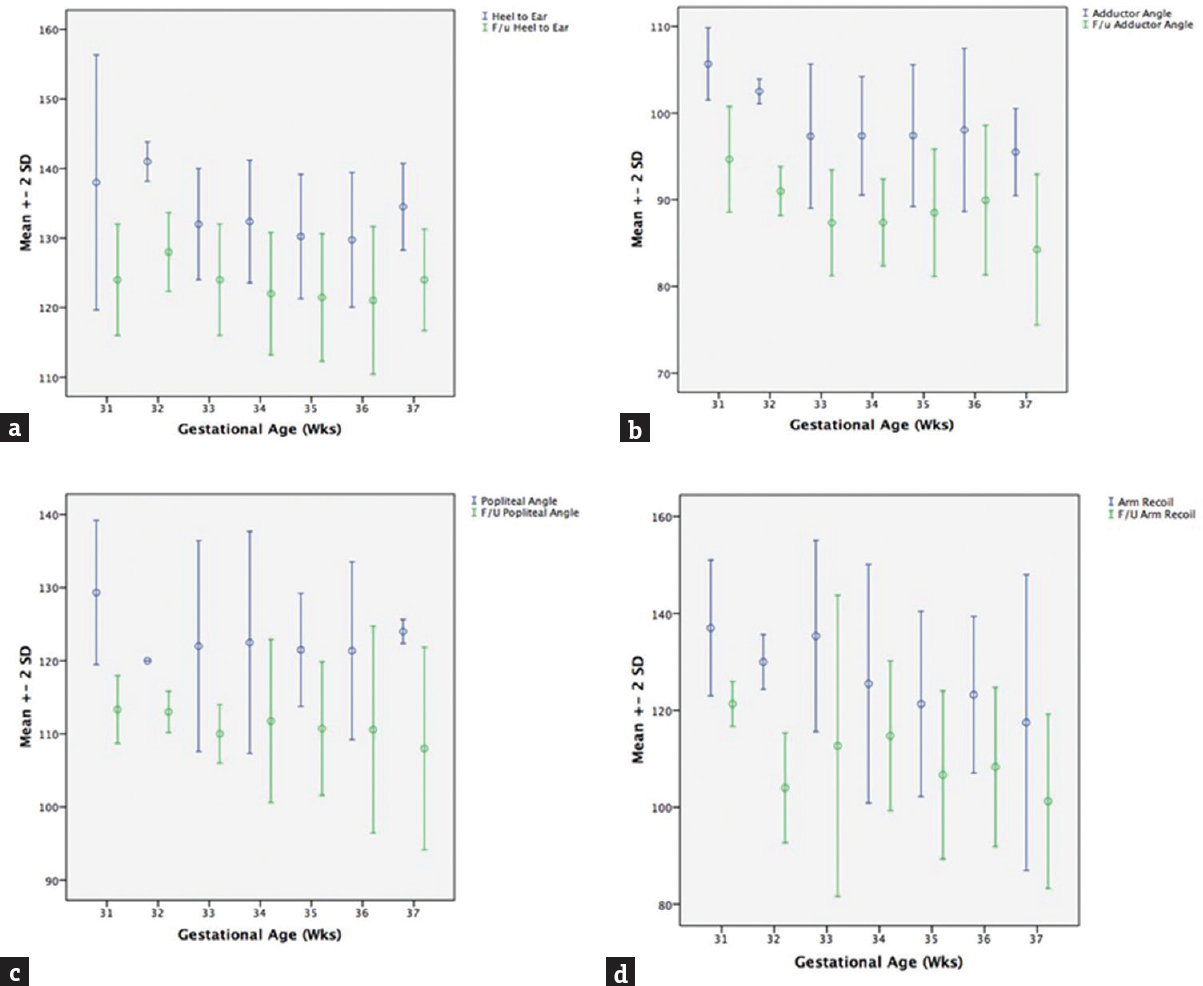

Totally 204 preterm infants between gestational age of 28 and 37 weeks were examined. The mean gestational age of preterm infants was 34.3 ± 1.7 at a mean age of 24 ± 13.9 h. No preterm <30 weeks could be enrolled because of the acute illness. The baseline tones of the preterms are tabulated in four different groups according to gestation along with the full-term infants (n = 74) in Table 1. The number of infants with gestational age from 30 to 32 weeks was 19, from 32 to 34 weeks was 38, and from 34 to 36 weeks was 84 and 36–37 weeks was 62. All infants showed <10° difference between rapid and slow angle. The preterm infants were reassessed at 40 weeks’ PCA and compared with full term. The groupwise multiple comparison by post hoc analysis shown in Table 2 indicates no significant difference in heel to ear and posture between the groups, indicating that these are the earliest parameter to mature and are independent of gestational age at birth. The graph plotted between gestational age at X-axis and angles in Y-axis shows that heel-to-ear angle matures consistently after 32 weeks while the other parameters adductor, popliteal angle and arm recoil mature after 36 weeks [Figure 1] indicating early development of caudal tone in preterm infant.

- Relationship of muscle tone of preterm infants at first assessment (blue lines) and at 40 weeks’ postconceptional age (green lines). Gestational age in weeks in X-axis and angles in degree in Y-axis (a: Heel-to-ear angle; b: Adductor angle; c: Popliteal angle; d: Arm recoil)

DISCUSSION

The present study showed significantly reduced flexor tone (popliteal angle, arm recoil, wrist flexion, and dorsiflexion) and adductor angle in preterm infants at 40 weeks’ PCA when compared to full term while posture, heel-to-ear angle, and scarf sign were not found to be significantly different. The literature review showed few studies evaluating this for preterm infants. One study described that preterm infant at 40 weeks’ PCA exhibits lower muscle tone, greater range of motion, so that their motility is more varied and of greater amplitude than the full-term infant.[12] Another study found that preterm infants have lower responses, especially on items involving muscle tone, despite higher levels of arousal.[17] Compared to these studies, the present study had preterm infants who were more mature at the first assessment (only 8% were <32 weeks).

Although we examined the infants at <72 h of life, no significant difference for posture was found between preterm and term infants. This suggests that stress of delivery may not play the influential role on maturation of posture. This was in accordance with previously published studies though the timing of examination differed in these studies from the present study.[1819202122] One study observed muscle tone assessment of preterm infants not to be influenced by birth weight, and the evolution is clearly related to PCA.

We measured heel-to-ear angle objectively by goniometer, whereas most of the previous studies have assessed them subjectively as scores. It is well known that passive tone maturation occurs in the caudocephalic pattern. A previous study has reported the sequential evolution of tone and reflexes from 25 weeks’ postmenstrual age (PMA) to 40 weeks’ PCA.[23] It found the lower extremity flexor tone to be first detectable at 29 weeks’ PMA as demonstrated by the popliteal angle and heel-to-ear maneuvers. Around 2–3 weeks after this, the upper limb tone could be detected by the maneuvers. The author postulated that two patterns of normal development are seen in the preterm infants: tone and reflexes appear in a caudocephalad (lower to upper extremities) and in centripetal (distal to proximal) manner.

Dorsiflexion angle of preterm infants at 40 weeks’ PCA was 52.7° ± 6.13°. All infants showed <10° difference between the rapid and slow angle. This is in accordance with Amiel-Tison which states that in the newborn period, the angle itself depends on the gestational age at the time of birth and ranges from 50° to 60° in very premature infants to nearly 0° in full-term infants.[24]

The functional anatomic approach by Sarnat explains the caudocephalic maturation.[25] There are two pathways in the control of motor function: corticospinal and subcorticospinal. The timing and direction of development differ in these two systems as myelination differs. The subcorticospinal system myelinates early and in caudocephalic direction (very rapid changes are observed from 24 to 34 weeks’ gestation). By 34 weeks, some of these pathways (medial) are fully myelinated while others (lateral) are partially myelinated. Antigravity activity is dependent on the lower system.

Strengths and limitations

The Present study is one of the first to measure the muscle tone of preterm infants with goniometer. The heel to ear was quantified and not scored which provides more objective assessment. This study postulated that heel to ear and posture can be taken as markers of neuromuscular maturity of preterm infants at 40 weeks’ PCA, irrespective of the gestation at birth. Any deviation in this angle can be taken as a marker for delayed maturation, follow-up, and early intervention is advisable in these cases. Limitations of the present study were small sample size, single-center data, noninclusion of <30 weeks’ gestational age, lack of further follow-up to correlate with development at 1 and 2 years age, and examination by trained pediatrician but not special neurodevelopmental pediatrician or physician. The maturation of Heel to ear angle is based on measurement of infants of different gestational age rather than following same cohort fortnightly. More number of studies or multicenter studies with larger sample and inclusion of preterm infants <30 weeks’ gestational age are required to validate the present study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Goniometric assessment provides a objective normative data of muscle tone for preterm infants. Maturation of heel to ear and posture evolves from 32 weeks onwards and are the earliest neurologic marker to mature in preterm infants independent of the gestational age at birth.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Consistency and change in the development of premature infants weighing less than 1,501 grams at birth. Pediatrics. 1985;76:885-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mortality of very low birth weight preterm infants in Brazil: Reality and challenges. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2005;81(1 Suppl):S111-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): A longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2008;371:813-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:9-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological assessment of preterm infants for predicting neuromotor status at 2 years: Results from the LIFT cohort. BMJ Open. 2013;3:E002431.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of gestational age and development at birth. Clin Obstet Biol Reprod. 1984;13:515-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical assessment of the infant nervous system. In: Levene MI, Lilford RJ, eds. Fetal and Neonatal Neurology and Neurosurgery (2nd ed). London: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. p. :83-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Update of the Amiel-Tison neurologic assessment for the term neonate or at 40 weeks corrected age. Pediatr Neurol. 2002;27:196-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interobserver reliability of the Amiel-Tison neurological assessment at term. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30:190-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interexaminer reliability of Amiel-Tison neurological assessments. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:347-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of developmental performance in preterm infants at two years of corrected age: Contribution of the neurological assessment at term age. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:799-804.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological development in the full-term and premature neonate. Paris: Masson; 1974. p. :6-10.

- Neurodevelopmental assessment in the first year with emphasis on evolution of tone. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:527-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr. 1991;119:417-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological and physical maturation in normal growth singletons from 37 to 41 weeks’ gestation. Early Hum Dev. 1999;54:145-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- A neurologic comparison of pre-term and full-term infants at term conceptional age. J Pediatr. 1976;88:995-1002.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of gestational age and birth weight in the clinical assessment of the muscle tone of healthy term and preterm newborns. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63:956-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Considerations in evaluating changes in outcome for infants weighing less than 1,501 grams. Pediatrics. 1982;69:285-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neurological examination of the full term newborn. Clinics in Developmental Medicine, No. 12. London: William Heinemann Medical Books; 1964.

- The neurological examination of non-complicated preterm newborns using the Saint-Anne Dargassies Scale from birth to term. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68:893-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological and neurobehavioural differences between preterm infants at term and full-term newborn infants. Neuropediatrics. 1982;13:183-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A method for neurologic evaluation within the first year of life. In: Meyer L, ed. Current Problems in Pediatrics. Vol 1. Chicago: Year Book Publishers; 1976. p. :1-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat HB, ed. Anatomic and physiologic correlates of neurologic development in prematurity. In: Topics in Neonatal Neurology. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1984. p. :1-25.