Translate this page into:

An observational study of foot lifts asymmetry during obstacle avoidance

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ujjawal Singh Tomar, Department of Physiotherapy, College of Applied Education and Health Sciences, Gangotri, Roorkee Road, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: ujjawalsinghtomar@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Specific information regarding obstacle-clearance strategies used by community-dwelling young and elderly is scant in the literature, and physical barriers encountered in real-life situations have not been used in most of the studies.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to determine foot lift asymmetry during obstacle avoidance in young and elderly subjects.

Settings and Design:

This was an observational study.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty elderly and 30 young individuals were taken for the study. All the subjects were evaluated using different scales and foot lift asymmetry was measured on a walkway using three obstacles of different heights.

Results:

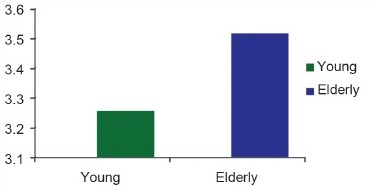

The mean and standard deviation (SD) value of the asymmetric index of the young was 3.25±0.28 and the mean and SD value of the asymmetric index of the elderly was 3.53±0.47. The asymmetric index of the elderly population was found to be higher than that of the younger population.

Conclusion:

The asymmetric index of the elderly population was found to be higher than that of the younger population, though it is not clinically significant.

Keywords

Elderly population

foot lift

obstacle avoidance

younger population

Introduction

Every individual experiences fallsthroughout life irrespective of his/her age. Falls in the elderly, by contrast, are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. It leads to consequences that vary from a minor injury to a significant loss of functional independence and even death.[1] A fall in persons over 65 is a result of the complex and poorly understood interaction of biomedical, physiologic, psychosocial, and environmental factors.[1]

It is estimated that 30% of the elderly in the community over 65 years, 40% of those over 80 years, and 66% of the institutionalized elders fall each year. There is a greater than linear increase in the rate of falls between 60–65 and 80–85.[1] Irrespective of the severity of the injury, consequences from even a benign fall can be devastating which can lead to a loss in confidence of one's ability to perform routine tasks, restriction of abilities, social isolation, and increased dependence on others. The ensuing deconditioning, joint stiffness, and muscle weakness that result from immobility can lead to more falls and further restrictions in mobility.[23]

The risk factors associated with falls can be classified into intrinsic (host) and extrinsic (environmental). Intrinsic factors include symptoms such as dizziness, weakness, difficulty in walking, or confusion, whereas environmental factors include slippery surfaces, loose rugs, poor surfaces, and obstacles.

Tinneti et al. found that intrinsic factors such as the use of sedatives, cognitive impairment, disability of lower extremities, palmomental reflex, and foot problems increase in community-dwelling elders over the age of 75.[4] Intrinsic factors constitute 45% of the falls, whereas extrinsic factors accountfor 39% of the falls.[5] It is likely that most of the falls are a result of complex interactions of intrinsic as well as extrinsic factors.[6] Cognitive impairment can include a loss of judgment in risk-taking behavior and has been strongly associated with a risk of falls.[3]

Yen et al. found in their study that there was an increased leading toe clearance but unaltered patterns of interjoint coordination in the elderly. Aging increased the variability of the way the joints of the lower limbswere controlled while crossing obstacles. There was no change in the pattern and variability of the interjoint co-ordination during the trailing-limb crossing in the elderly, possibly because they were able to meet the mechanical demands.[7]

Specific information regarding obstacle-clearance strategies used by community-dwelling young and elderly is scant in the literature. Physical barriers encountered in real life situations have not been used in most of the studies. Thus, this study attempts to determine foot lift asymmetry during obstacle avoidance in the young and elderly population.

Materials and Methods

This was an observational study. Healthy youngparticipants were taken from College of Applied Education and Health Sciences and healthy older people were taken from the LalaLajpatRai Medical College who were either visiting the hospital as a care taker or were accompanying the patients.

Thirty young male individuals (18–30 years) and 30 elderly male individuals (above 65 years) were taken in the study by means of convenient sampling. Individuals who could read, write, understand, follow commands, with normal hearing, who were able to distinguish between three different types of sounds, and who hada normal range of motion (ROM)of jointsand hip-knee strength were included in the study.

The subjects excluded in the study were the high-risk elderly, uncooperative subjects, subjects witha neurological disorder like stroke, spinal cord injury, parkinsonism,and so on,those withan orthopedic condition like total hip replacement (THR), total knee replacement(TKR), an injury of the lower limbsor fractures, patientswith loss of hearing, patients who were unable to distinguish between different types of sounds,orthose having restricted ROM or decreased hip-knee strength.

Procedure

We evaluated all the subjects using the following tests or scales: Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Trail-Making Test (TMT) A and B, Timed Up and Go (TUG), and Choice Stepping Reaction Time (CSRT).

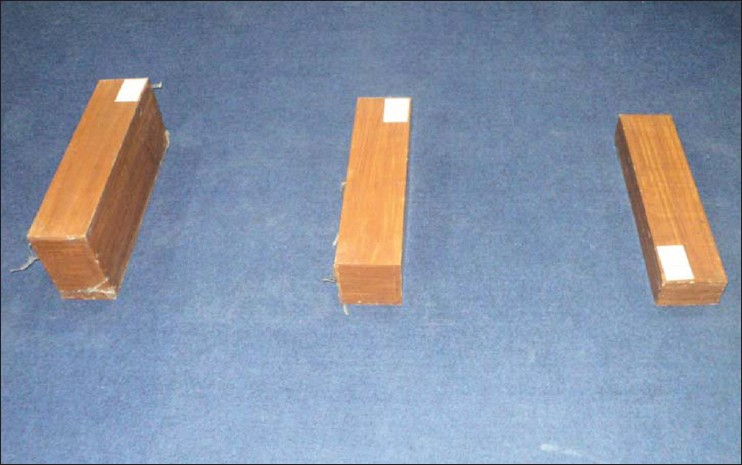

Footlift asymmetry was measured on a walkway of 70 inches. Three obstacles of different heightsof 7.6cm, 12.7cm, and 20.3cm were placed on a walkway at equal distances(20 inches), as seen in Figure 1. The width and length of each obstacle was 5 and 20 inches, respectively. The individual was made to step barefoot over the various-sized obstacles placed on a cemented surface. It was natural walking with one foot after the other. The subjects were allowed to choose between leading and trailing foot. Data was recorded using a video camera, and foot lift was measured by calculating the vertical distance between toe and the surface of the obstacle using SportsCad analysis software.

- Obstacles of different heights

The mean of the readings obtained for lead as well as for lag foot during clearance of small-, medium-, and large-sized obstacle was calculated and recorded for both the groups. Later, asymmetry index was calculated (asymmetry index = lead foot - lag foot), which is a measure of foot lift above the obstacle.

Data was analyzed by using descriptive statistics.

Results

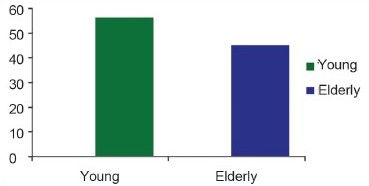

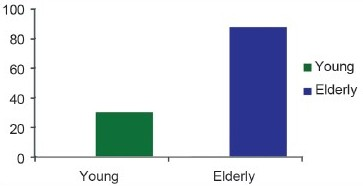

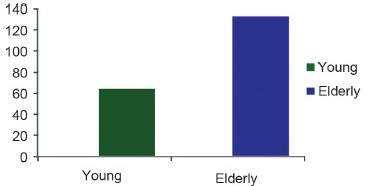

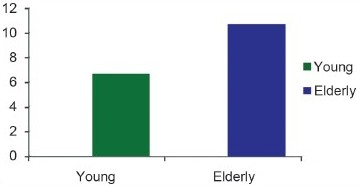

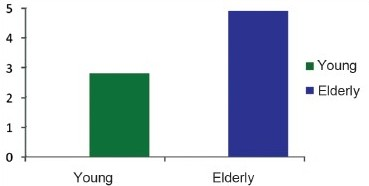

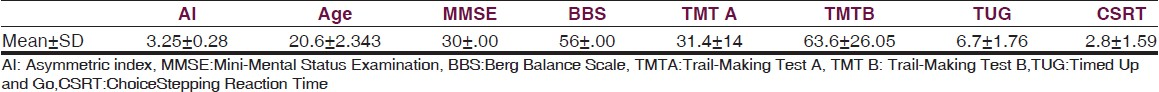

For the young subjects, the mean and SD value of the asymmetric index was 3.25±0.28 [Graph 1], of MMSE was 30±.00 [Graph 2],of BBS was 56±.00 [Graph 3], of TMT A was 31.4±14 [Graph 4], of TMT B was 63.6±26.05 [Graph 5], of TUG was 6.7±1.76 [Graph 6],and of CSRTwas 2.8±1.59 [Graph 7]. This is also depicted in Table 1.

- Mean of the asymmetric index ofthe young and the elderly

- Mean of the Mini-Mental Status Examination of the young and the elderly

- Mean of the Berg Balance Scale of the young and the elderly

- Mean of the values of the Trail-Making Test A of the young and the elderly

- Mean of the values of the Trail-Making Test B of the young and elderly

- Mean of the values of the Timed Up and Go Test ofthe young and the elderly

- Mean of the values of the Choice Stepping Reaction Time of the young and the elderly

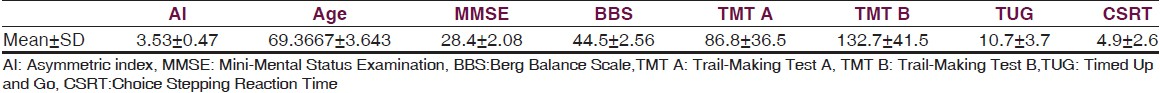

For the elderly subjects, themean and SD value of the asymmetric index was 3.53±0.47 [Graph 1],of MMSE was 28.4±2.08 [Graph 2],of BBS was 44.5±2.56 [Graph 3],of TMTA was 86.8±36.5 [Graph 4], of TMT B was 132.7±41.5 [Graph 5],of TUG was 10.7±3.7 [Graph 6],and of CSRT was 4.9±2.6 [Graph 7]. This is also depicted in Table 2.

Discussion

This was an observational study and we found the asymmetry index of the elderly population more than that of the younger population. The result of our study is consistent with a previous study done by Fabio et al. in 2004 who found that there was a marked asymmetry in foot clearance in the elderly people while stepping over an obstacle. The possible mechanisms proposed as responsible for this was limited hip extension and deficits in executive cognitive functions.[8]

The high asymmetry index for the elderly might be related to the group-specific loss of hip extension. Once the step over the obstacle is initiated, the hip of the lag limb must extend before the liftof the lag foot in the elderly. The study done by Kerrigan and colleagues in 1999 found that the elderly fallers showed a consistent reduction in hip extension during walking.[9]

Additional research is needed to determine whether increases in hip motion with stretching exercises will reduce the incidence of falling in the elderly,[10] as suggested by Kerrigan. It is unlikely that strength, proprioception ofthe lower extremities, or deficits in balance contributed to differences in foot lift symmetry between the elderly cohorts, because group scores of the elderly on these measures were statistically equivalent.

We also found MMSE score in the elderly lower as compared to that of the young participants. This would also have an effect on their foot lift. This is suggested by a study done by Nevittet al. that control of limb movements over an obstacle requires initiation of footlift without visual input. Subjects must use memory to plan and execute footlift, and this plan presumably involves executive cognitive functions. Slow trail-making times have been associated with an increased risk of major fall-related injuries by Nevitt and colleagues in 1991.[11]

We also found that the elderly population took more time to perform the TMT as compared to the younger participants. Poor performance on TMT could be associated with prolonged stepping reaction time, as suggested by Lord et al. and in turn would have affected the foot lift.[12]

Conclusion

The asymmetric index of the elderly population was found to be higher than that of the younger population, though it is not clinically significant.

Limitation of the study

Only male subjects wereincluded in the study. There can be an error in measurement in the video graphic analysis of foot lift. Another limitation of the study is that we did not analyze the movement patterns.

Clinical message

Rehabilitate the elderly is helpful while focusing on physical barriers encountered in real-life situations.In addition to uneven terrain,foot lift asymmetry in the elderly can be a factor contributing to falls.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Fear of falling and postural performance in the elderly. J Gerontol. 1991;46:M123-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Falls in older persons; Risk factors and prevention. In: Berg RL, Cassells JF, eds. The second Fifty years: Promoting Health and Preventing Disability. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine National Academy Press; 1990. p. :63-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in community. N EnglJ Med. 1988;319:1701-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Falls in the elderly: Reliability of a classification system. J Am GeriatrSoc. 1991;39:197-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Causes and correlates of recurrent falls in ambulatory frail elderly. J Gerontol. 1991;46:M114-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age effects on the inter-joint coordination during obstacle-crossing. J Biomech. 2009;42:2501-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gait adjustments in response to an obstacle are faster than voluntary reactions. HumMovSci. 2004;23:351-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced hip extension during walking: Healthy elderly and fallers versus young adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;84:26-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a hip flexor- stretching program on gait in the elderly. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Choice stepping reaction time: A composite measure of falls risk in older people. J Gerontol A BiolSci Med Sci. 2001;56A:M627-32.

- [Google Scholar]