Translate this page into:

The Self-Stigma of Depression Scale: Translation and Validation of the Arabic Version

Address for correspondence: Dr. Hussain Ahmed Darraj, Jazan Health Affairs, Ministry of Health, P. O. Box: 1075, Abu Arish 45911, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: dr.h.d@hotmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Self-stigma may feature strongly and be detrimental for people with depression, but the understanding of its nature and prevalence is limited by the lack of psychometrically validated measures. This study is aimed to validate the Arabic version self-stigma of depression scale (SSDS) among adolescents.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study involved 100 adolescents randomly selected. The analyses include face validation, factor analysis, and reliability testing. A test–retest was conducted within a 2-week interval.

Results:

The mean score for self-stigma of depression among study participants was 68.9 (Standard deviation = 8.76) median equal to 71 and range was 47. Descriptive analysis showed that the percentage of those who scored below the mean score (41.7%) is shown less than those who scored above the mean score (58.3%). Preliminary construct validation analysis confirmed that factor analysis was appropriate for the Arabic-translated version of the SSDS. Furthermore, the factor analysis showed similar factor loadings to the original English version. The total internal consistency of the translated version, which was measured by Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.77 for the four subscales and 0.84 for the total scale. Test–retest reliability was assessed in 65 respondents after 2 weeks. Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.77 for the four subscales and 0.84 for the total scale.

Conclusions:

Face validity, construct validity, and reliability analysis were found satisfactory for the Arabic-translated version of the SSDS. The Arabic-translated version of the SSDS was found valid and reliable to be used in future studies, with comparable properties to the original version and to previous studies.

Keywords

Cronbach's alpha

depression

Jazan

mental health

self-stigma

INTRODUCTION

Stigma and burden related to depression are common all over the world.[12] Recent research has highlighted stigmatizing beliefs as an important barrier for seeking help of mental health services.[345] Corrigan has proposed a framework in which stigma is categorized as either public stigma or self-stigma. Within each of these two areas, stigma is further divided into three elements: stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.[6]

Self-stigma is defined as the reduction in a person's self-esteem or sense of self-worth due to the perception held by the individual that he or she is socially unacceptable.[7] Self-stigma is thought to occur when people experiencing a mental illness or seeking help self-label as someone who is socially unacceptable and in doing so internalize stereotypes, apply negative public attitudes to themselves, and suffer diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy.[8] Common demonstrations of self-stigma include feeling shame and limiting integration with others.[9] Researchers have also noted that individuals who self-stigmatize may avoid seeking psychological services to avoid being labeled as having a mental illness.[10]

Self-stigma involves the internalization of public negative beliefs and attitudes by an individual with depression. Self-stigma can cause people with depression to lose hope for recovery, avoid seeking help, and delay or terminate early treatment.[1112]

The aim of this paper is to translate the English-language version of the self-stigma of depression scale (SSDS) into Arabic and to validate the Arabic-language version among adolescents so that it could be used in Arabic-speaking populations. Face validity, internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and construct validity were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Self-stigma of depression scale

Barney et al. developed the SSDS with input from focus group discussions including persons with and without a history of depression, and a literature review conducted by the researchers. However, the SSDS is designed to assess the extent to which a person holds stigmatizing attitudes toward themselves in relation to having depression. It is a 16-item scale with four subscales: shame, self-blame, social inadequacy, and help-seeking inhibition. Responses to the self-stigma items are measured on a five-point scale (ranging from one “strongly agree” to five “strongly disagree”). Items are coded so that a higher score indicates greater self-stigma. Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.78 to 0.83 for the four subscales and 0.87 for the total scale. Test–retest reliability was assessed in 151 respondents after 2 months. Intraclass correlation coefficients are (ICCs) 0.63. In Chinese version of SSDS, internal consistency is α = 0.874 and test–retest reliability is r = 0.824.[13] Stigma scores were stratified for gender and depression experiences, but no minimally important change was defined.[14]

Study design and participants

This study employed a cross-sectional study design. The source population was adolescent students in Jazan City. Two intermediate and two secondary schools for boys and girls were randomly selected. The number of study participants for each phase was determined according to the type of validation method. Thirty students were recruited in Phase 1 to assess face validity, whereas in Phase 2 for construct validity, the sample size was calculated depending on based on method presented by Gorsuch.[15] For reliability testing, the required sample size was calculated based on the Cronbach's alpha formula. Taking into consideration 10% dropout. The final required sample size was 120 participants. In test–retest phase (Phase 3), the sample size was based on ICC (Walter et al., 1998). The minimally acceptable ICC value (r 1 = 0.7) versus an alternative ICC value reflecting the expectations (r 1 = 0.8) was chosen, with the power of 80% and a significance level of 5%; the required sample size was forty participants.[16]

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

The planned procedures for translating the SSDS were based on the guidelines of translation and cross-cultural adaptation by Beaton et al.[17] Translation and back translation were conducted to confirm accuracy and appropriateness of SSDS wording. The instrument was translated by two independent persons from English into Arabic at the same time. One of them was aware of the study's purpose and goals, and the other one was not. Both translators had discussed the differences between their translations to resolve any differences until they develop a consensus about the Arabic wording of each item. Two back translations into English were done by two independent persons. The back translation was conducted with no prior exposure to the English-language version of the questionnaire. Then, Expert Committee Review was conducted. Principal investigator, translators, Arabic language expert, social expert, and psychiatrist discussed any discrepancies found between the original D-Lit and items and the back-translated versions of the questionnaire. The committee also assessed the suitability of the instrument to be used at the level of adolescents, and it was appropriate. To avoid any limitation on the applicability of this version of the scale, the final translation was in classic Arabic, which can be used in other Arab countries with different dialects. Which was similar to the English version in content and structure. Then, face validity was conducted as shown in this study.

Data collection

The data collection was conducted at each respective school in Jazan City. There was no missing data. In Phase 1, face validation was conducted. The selected participants (n = 30) were asked to go through the Arabic version of the SSDS. After reading through the instrument, they were asked if they fully understood the instrument and its meaning. There are no difficulties met the participants with the translated instrument. In the second phase, construct validation and reliability testing were conducted. The Arabic version of the SSDS was distributed to the participants (n = 120). The researcher briefly explained the content and how to answer the instrument before asking the participants to complete the instrument. The participants were encouraged to ask if they had any problem with the instrument. The average time was taken to complete the instrument was 15 min. These completed instruments were returned to the researcher. At the end of Phase 2, no participants had indicated problems with the Arabic version of the SSDS. The Phase 3, which was the test–retest reliability, was conducted after a 2-week interval. In this phase, we have been able to reach 65 participants who had involved in Phase 2 and the same Arabic version of the SSDS was given to them. It was to test if the participants would provide the same answer as in the previous phase. The same procedures were repeated similarly to the Phase 2.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) (version 19 Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic information and to obtain the descriptive details of depression literacy among the participants. To assess the factor structure of the translated version of the SSDS before factor analysis, the preliminary analysis which indicates the adequacy of the instrument for factor analysis was evaluated. The preliminary analysis is represented by the value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy (MSA), individual MSA, and Bartlett's test of sphericity. The KMO value is expected to exceed the acceptable limit of 0.50,[18] Finally, Bartlett's test of sphericity indicates the appropriateness of factor analysis for the translated instrument,[19] thus it is expected to be significant. The analysis then proceeded with an assessment of the factor structure. Since confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using SPSS application. Assessment of the factor structure includes factor loading where items that are highly loaded into each factor was examined and then compared to previous studies. To assess the reliability of the Arabic version of the SSDS, the internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the translated instrument were measured. The internal consistency reliability of the instruments is represented by Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α). Subsequently, Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) was calculated to evaluate the test–retest reliability. The correlation coefficient was calculated for the total score of the translated instrument.

Ethical considerations

The study proposal and instrument were approved by the faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee. Authorization was granted from the headmasters of the selected schools. During the distribution of the questionnaire, students were informed that the information collected would be kept anonymous and that participation was completely voluntary. Informed consent was sought from the eligible participants following full disclosure regarding the study before data collection is done. Proxy consent for children was obtained from parents or the responsible. The purpose of the study was explained. The participants were assured that they may withdraw from the study at any time during the study.

RESULTS

Descriptive results

The participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 19 years (Mean = 15.3 years, standard deviation [SD] = 1.68 years). The summary of participant's demographic information is shown in Table 1. In the current study, the mean score for depression self-stigma among the participants is 68.9 (SD = 8) median is 71 and range is 33–80. The descriptive summary of the Arabic-translated version of the SSDS among the participants is tabulated in Table 1. Based on the mean score, the participants were divided into two groups; participants who scored below the mean score and participants who scored above the mean score. The percentage of those who scored below the mean score was (41.7%) less than those who scored above the mean score (58.3%).

Reliability testing

The internal consistency of the Arabic-translated version of the SSDS was found Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.77 for the four subscales and 0.84 for the total scale. This reliability estimate exceeded the recommended criterion for internal consistency of at least 0.70.[20] The item-to-total score correlations were between r = 0.30 and r = 0.60, with 16 items exceeded the 0.30 criterion.[21] Test–retest reliability was assessed in 65 respondents after 2 weeks. Pearson correlation ranged from 0.72 to 0.78 for the four subscales and 0.77 for the total scale.

Readability testing

Gunning Fog index is 5.88 for the Arabic version of SSDS which indicates the number of years of formal education that a person requires to easily understand the questions in the SSDS on the first reading.

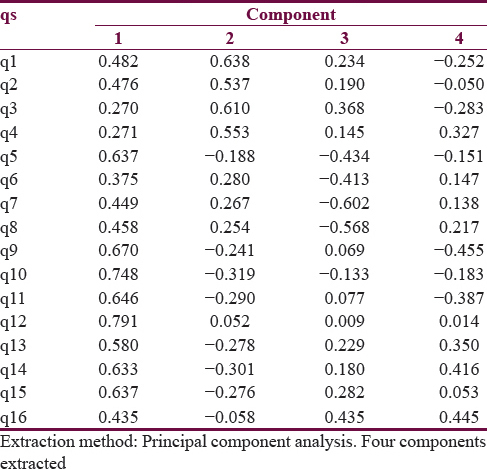

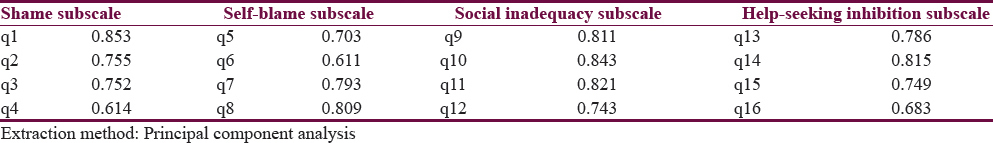

Factor analysis

The preliminary analysis for factor analysis of the Arabic-translated version of the SSDS showed a satisfactory result. The determinant is >0.00001. The value of the KMO MSA was 0.79. Nevertheless, since the value of KMO exceeded the recommended value of 0.60,[22] the analysis proceeded with all items regardless of the individual MSA. In addition, Bartlett's test of sphericity was found highly significant (P < 0.001). The factor loading of the translated instrument is shown in Table 2. The table confirms that all items of the scale have been explained by a single factor (component 1). For the subscales: shame (Q1-Q4), self-blame (Q5-Q8), social inadequacy (Q9-Q12), and help-seeking inhibition (Q13-Q16), the factor analysis was conducted for each subscale alone to confirm the items correlation to subscale as one factor component because we have found the determinants >0.00001, value of KMO exceeded the recommended value, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was found highly significant (P < 0.001), and the correlation between items and subscale has been adequate as shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the 16-item SSDS. The results provide solid support for the scale's reliability and validity among adolescent school students. Reliability was demonstrated through adequate estimates of internal consistency; Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.77 for the four subscales and 0.84 for the total scale, which exceeds the minimum criterion of 0.70.[20] This internal consistency estimate is consistent with the findings from other studies of SSDS measures, which reported Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.78 to 0.83 for the four subscales and 0.87 for the total scale, and for the Chinese version of SSDS internal consistency is α = 0.87.[13] Test–retest reliability in our study for SSDS was assessed in 65 respondents after 2 weeks. Pearson correlation ranged from 0.72 to 0.78 for the four subscales and 0.77 for the total scale. In contrast with the original version of SSDS which found test–retest reliability in 151 respondents after 2 months ranged from 0.49 to 0.63 and 0.63 for total.[14] On another hand, the test–retest reliability of Chinese version of SSDS is r = 0.82.[13]

The corrected item-to-total correlations for 16 items exceeded the 0.30 criterion[21] suggesting the homogeneity of the measure and that each item was measuring a unique construct. This finding was not reported in the original English version of the SSDS.

The findings of the factor analysis provide further support for the construct validity of the Arabic SSDS. All items have been explained by the whole scale, and items of subscale also have been correlated which indicate that the Arabic version of the SSDS is valid to measure depression Stigma.

Gunning Fog index was 5.88 for the Arabic version of SSDS which indicates the number of years of formal education that a person requires to easily understand the questions in the SSDS on the first reading. This confirms that SSDS is appropriate for the level of adolescent students.

Limitations

Around half (n = 65) of participants were dropped during the second time test to fill the same questionnaire, compared to participants in the first time test (n = 120), this dropout was due to midterm examinations, but still it was a statistically appropriate sample for test-retest as the minimal sample size was calculated to be above of forty participants.

CONCLUSION

The findings from this analysis of the psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the SSDS in adolescent school students yield promising evidence that the 16-item SSDS has acceptable reliability and validity. The findings also indicate that the SSDS is potentially useful for assessing depression self-stigma that precedes the designing of depression destigmatization programs and monitors the effectiveness of these interventions to produce the desired change among adolescent school students, which is important for compacting depression stigma and improve help-seeking behavior. This study provides evidence that supports the face validity, content, construct validity, and reliability of the SSDS for adolescent school students.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ahmed Abo El Yazid, for his valuable comments and suggestions in the early work. Furthermore, we thank the staff from Jazan University, for their efforts in supervising the data collection phase. We appreciate the efforts of the Education Directorate in Jazan Region, administrative staff and teachers for coordination and help with data collection. Furthermore, we would like to thank Professor Kathy Griffiths, for permission to use the Depression Literacy Questionnaire.

REFERENCES

- Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: The GAMIAN-Europe study. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:56-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Personal and perceived depression stigma in Australian adolescents: Magnitude and predictors. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:104-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1592-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adaptation and translation of mental health interventions in Middle Eastern Arab countries: A systematic review of barriers to and strategies for effective treatment implementation. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59:671-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54:40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:907-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative investigation of self-stigma among adolescents taking psychiatric medication. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:893-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding and influencing the stigma of mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2008;46:42-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring self-stigma of mental illness in China and its implications for recovery. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:408-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Validation of Chinese Version of Self-Stigma of Depression Scale in Psychiatric Outpatients with Depression in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists. Available from: http://www.hkcpsych.org.hk/index.php?option=com_docman&view=docman&Itemid=414&lang=en &limitstart=50

- The Self-Stigma of Depression Scale (SSDS): Development and psychometric evaluation of a new instrument. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19:243-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factor Analysis (2nd ed). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 1983.

- Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3186-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (3rd ed). London: Sage publications Ltd; 2009.

- Statistical foundations. Psychometric Theory (3rd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. p. :31-208.

- How to Use SPSS: A Step-By-Step Guide to Analysis and Interpretation. Los Angeles, CA: Pyrczak Publishing; 2004.

- Cleaning up your act: Screening data prior to analysis. Using Multivariate Statistics (5th edition). Boston: Pearson Education Inc/Allyn and Bacon; 2007. p. :60-116.