Translate this page into:

Synchronous Pediatric Supratentorial Glioblastoma Multiforme with Noncontiguous Infratentorial Pilocytic Astrocytoma: A Rare Event

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Multicentric gliomas of the central nervous system are rare lesions with an estimated incidence being 2.4%–4.9% of all gliomas.[1] Even more uncommon are the ones which arise in the supra- and infra-tentorial compartments, especially of different histopathological subtypes. We present the first pediatric case of a multicentric bi-compartmental glioma of different histopathological subtypes.

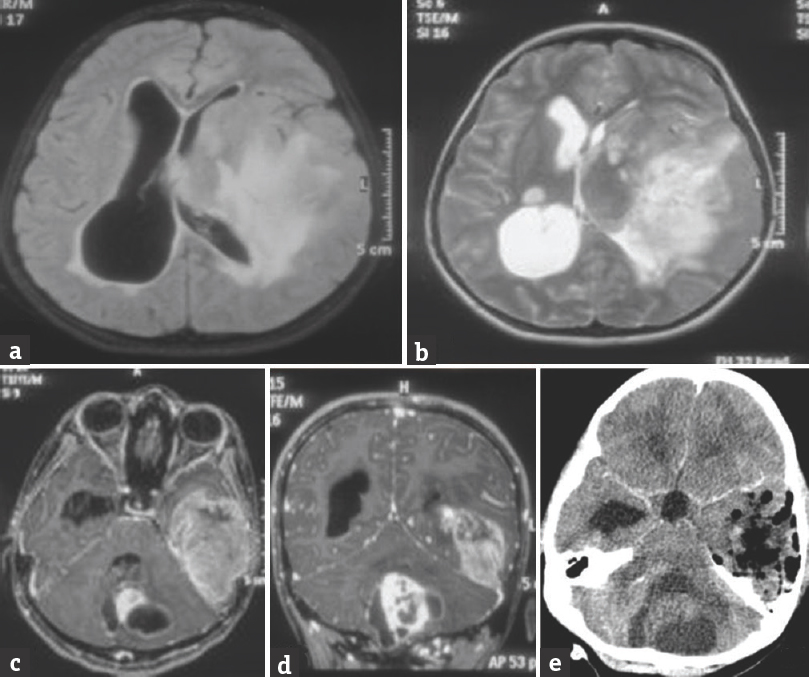

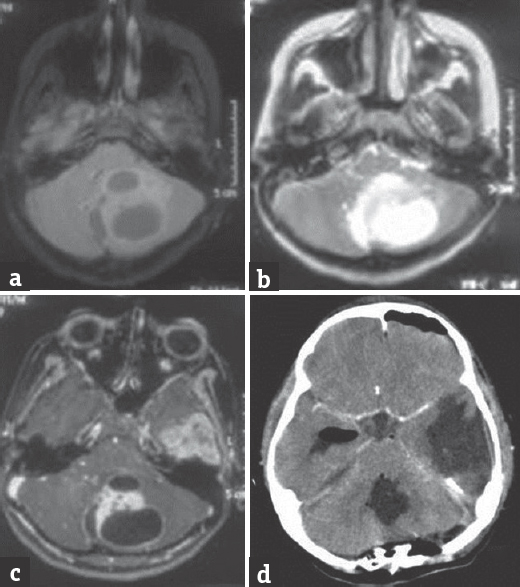

A 12-year-old girl presented with chief complaints of generalized headache with vomiting and blurring of vision at peak of headache; features suggestive of raised intracranial pressure for a total duration of 3 months. Historically, she also reported to have difficulty in maintaining balance while walking for 1-month duration. She had previously been asymptomatic and had no positive history for other medical or surgical illnesses. On neurological examination, the patient was conscious oriented, and the higher mental functions were normal. The motor and cerebellar examination revealed weakness of the right upper and lower limb with grade 4/5, gross truncal ataxia with bilateral horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus. Fundus examination showed bilateral papilledema. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the brain showed a diffuse lesion in the left temporal lobe with significant mass effect on ipsilateral white matter and lateral ventricle with midline shift of 1.3 cm and evidence of uncal herniation. The lesion was hypointense on T1, hyperintense on T2, enhancing brightly, and heterogeneously on contrast administration with central nonenhancing part suggesting necrosis. The size of this lesion was approximately 6.8 cm × 4.5 cm × 3.9 cm [Figure 1a-e]. The other lesion was in the posterior fossa involving the cerebellar vermis with extension into the left cerebellar hemisphere having imaging characteristics similar to the lesion in the left temporal lobe. The lesion showed peripheral dense enhancement with central necrotic area. The size of this lesion was approximately 4.40 cm × 4.00 cm × 3.17 cm [Figure 2a-d].

- (a) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial magnetic resonance image showing left temporoparietal lesion with diffuse cerebral edema and mass effect. (b) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance image showing hyperintense left temporoparietal lesion. (c) T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance image with gadolinium injection showing diffuse enhancement in left temporal lesion with partial but brilliant enhancement in the vermian lesion. (d) T1-weighted coronal magnetic resonance image after gadolinium injection showing contrast-enhancing lesions in the left temporal lobe and vermis. (e) Postoperative computed tomography scan (with contrast) image after the first surgery showing good decompression of the left temporal lesion with no contrast-enhancing residue or hematoma

- (a) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial magnetic resonance image showing vermain lesion with left cerebellar hemispheric extension. Cystic areas can be appreciated in this lesion. (b) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance image showing hyperintense vermain lesion with compression over the brain stem. (c) T1-weighted axial magnetic resonance image after gadolinium injection showing enhancing part of vermain lesion with cystic changes in left cerebellar hemispheric lesion. (d) Postoperative computed tomography scan (with contrast) image after the second surgery showing near total resection of the vermian lesion with no contrast-enhancing residue or hematoma

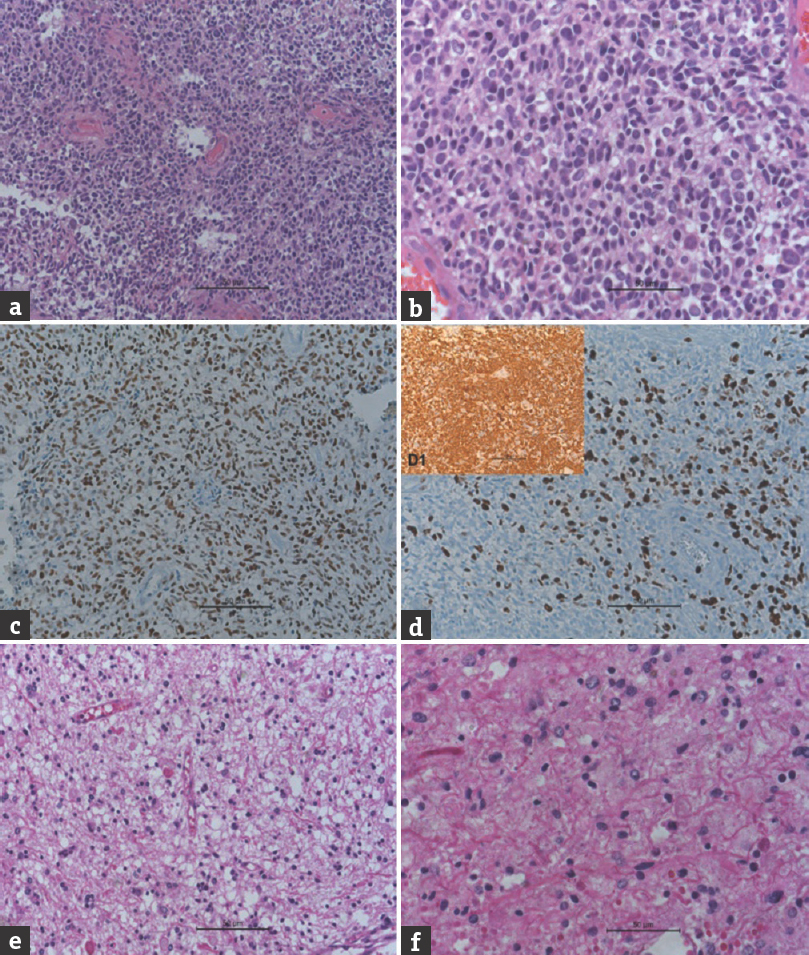

The patient underwent left temporoparietal craniotomy and near total decompression of the tumor. The lesion was grayish, soft, and friable with moderate vascularity. Histopathology of the temporal lesion showed a densely cellular neoplasm with cells being round-to-ovoid, hyperchromatic, and exhibiting high N:C ratio, scanty, clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm with the areas of necrosis, and microvascular proliferation [Figure 3a and b]. The tumor cells showed a high p53 labeling [Figure 3c]. The MIB-1 labeling was high [40%, Figure 3d]. The tumor cells were positive (strongly) for glial fibrillary acidic protein [Figure 3d1 inset]. These characters were diagnostic of glioblastoma (GBM) (small cell), the WHO grade-IV. Histopathology of the cerebellar lesion showed a relatively hypocellular neoplasm with bland round vesicular nuclei, abundant piloid fibers, numerous eosinophilic granular bodies and Rosenthal fibers, and vascular proliferation [Figure 3e and f]. These features were characteristic of pilocytic astrocytoma (WHO grade-I). Subsequently, she underwent midline suboccipital craniectomy and subtotal resection of the posterior fossa lesion. She underwent chemoradiation for the left temporal lesion and has improvement in weakness of limbs compared to preoperative status, without any fresh deficit.

- (a) Microphotograph showing undifferentiated glial cells of glioblastoma (H and E, ×200). (b) Microphotograph showing undifferentiated glial cells of glioblastoma (H and E, ×400). (c) Microphotograph showing p53 staining of the tumor cells (immunohistochemistry, p53, ×200). (d) Microphotograph showing MIB-1 staining of the tumor cells (immunohistochemistry, MIB-1, ×200]. (d1 inset) Microphotograph showing glial fibrillary acidic protein staining of the tumor cells (immunohistochemistry, GFAP, ×200). (e) Microphotograph showing pilocytic astrocytoma with Rosenthal fibers and eosinophilic granular bodies (H and E, ×200). (f) Microphotograph showing pilocytic astrocytoma with Rosenthal fibers and eosinophilic granular bodies (H and E, ×400)

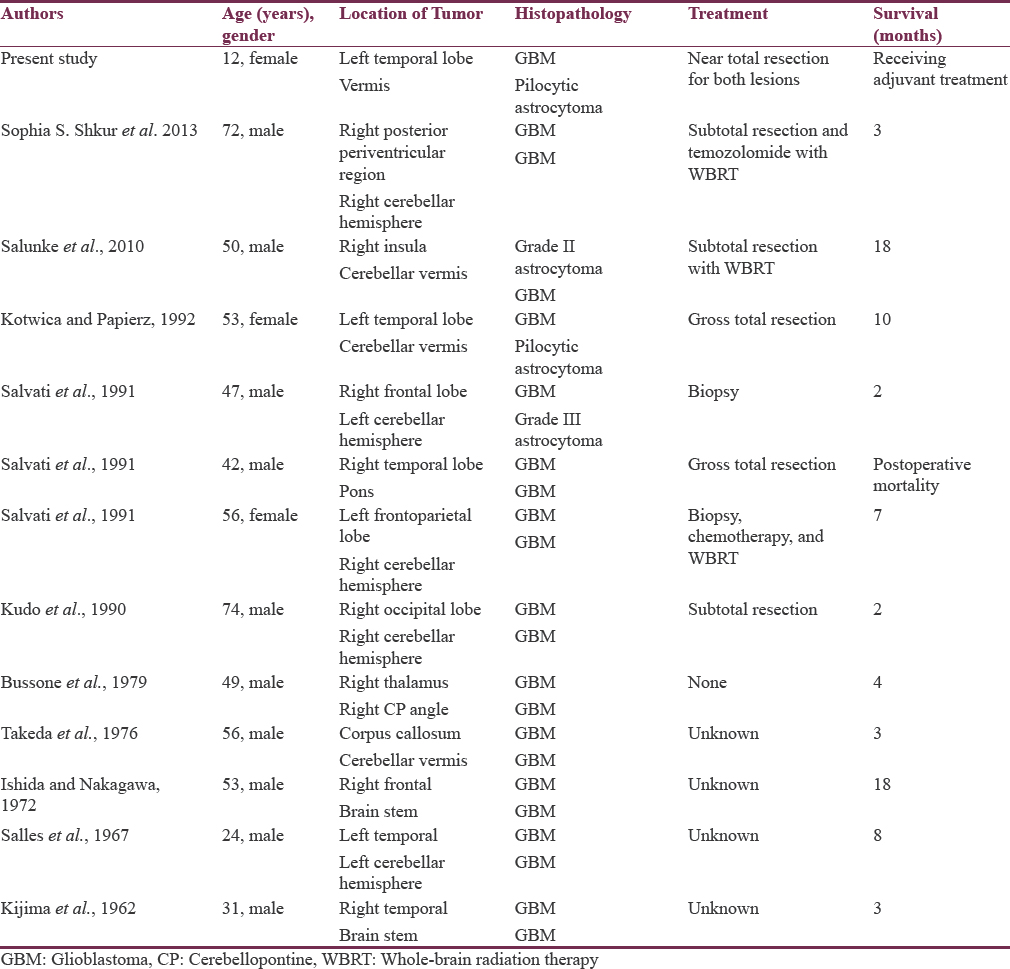

GBMs are the most common intraparenchymal primary brain tumor, representing approximately 30% of all brain tumors [Table 1]. The multiple gliomas can be classified as “multifocal” if there is an apparent route of dissemination (i.e., a white matter tract). In contrast, if there is no obvious pathway for spread, it is termed multicentric. Multifocal glioma consists of tumors separated by white matter tracts within the same hemisphere, whereas multicentric glioma consists of noncontiguous tumors in opposite hemispheres or separated by the tentorium. Multicentric gliomas involving the supratentorial and infratentorial regions are very rare.[23] In an autopsy series, incidence of multifocal glioma was found to be 27.8% of cases, and the ratio of multiple to multicentric gliomas was 10.6:1.37. Review of the pertinent documented literature revealed that only 12 other cases of concomitant supratentorial and infratentorial glial tumors have been documented. Historically, multifocal and multicentric GBMs have been associated with a worse prognosis than solitary GBM, with median patient survival estimates of 6–8 months after different treatment modalities.[4] Tumor dissemination at the time of diagnosis can also serve as a prognostic marker. One study stratified patients into three groups based on solitary or multifocal tumors and whether there was subependymal or subarachnoid dissemination at the time of diagnosis.[5]

According to certain theories, multicentricity arises from two events.[2] The first stage is neoplastic transformation, in which a wide field becomes more susceptible to neoplastic growth. The second stage is tumor proliferation at two or more activated sites that can occur simultaneously in response to various stimuli including biochemical, hormonal, and viral triggers. More contemporary theories have looked at molecular associations. For example, there is a reported association between p53 mutations and multifocal GBM that correlates the pattern of p53 mutation to tumor migration and augmented growth.[6] In a study of the growth factor receptor c-Met in GBM, one group found that 42.9% of tumors that overexpressed c-Met displayed invasive and multifocal features on initial MR imaging, whereas only 17.1% of tumors with little or no c-Met expression had similar characteristics (P = 0.036).[7] Other studies have correlated the tumor pattern at diagnosis and recurrence with the spatial relationship to the subventricular zone (SVZ) and cortex as seen on MR imaging.[8] Neural stem cells within the SVZ may give rise to multiple and multicentric GBMs. Neural stem cells have been found to express matrix metalloproteinases, which are proteolytic enzymes implicated in tumor spread.[9]

To summarize, we present a report of multicentric glioma in a child, which has never been documented in literature earlier. Currently, there are no clear guidelines regarding the optimal management of multifocal and multicentric GBM.[3] Aggressive resection of one tumor focus, biopsy alone followed by chemoradiation, and multiple craniotomies during a single operation have all been described with no clear indication of which modality is superior.[810]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Multicentric glioblastoma multiforme occurring in the supra- and the infratentorial regions – Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1990;30:334-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple craniotomies in the management of multifocal and multicentric glioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:576-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic significance of intracranial dissemination of glioblastoma multiforme in adults. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:622-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic analysis of a multifocal glioblastoma multiforme: A suitable tool to gain new aspects in glioma development. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1377-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic significance of c-Met expression in glioblastomas. Cancer. 2009;115:140-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebellar glioblastoma multiforme with non-contiguous grade 2 astrocytoma of the temporal lobe in the same individual. Neurol India. 2010;58:651-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of glioblastoma multiforme to neural stem cell regions predicts invasive and multifocal tumor phenotype. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:424-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multifocal glioblastoma multiforme: Prognostic factors and patterns of progression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:820-4. mpairment in people living with AIDS. Indian J Psychiatry 2012;54:149-53

- [Google Scholar]