Translate this page into:

Scrub typhus with opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia-seizure as primary presentations

*Corresponding author: Sumirini Puppala, Department of Neurology, IMS and SUM Hospital, SOA University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. sumirini@ymail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Puppala S, Acharya A, Choudhury SS. Scrub typhus with opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia-seizure as primary presentations. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:143-7. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_314_2023

Abstract

Scrub typhus is a simple acute febrile illness with rash or an eschar, with up to one-fifth of the patients complicated with the nervous system. Hence, certain cases present to physicians with rather a different systemic manifestation and incidentally have been diagnosed with scrub typhus. We present two such cases of scrub typhus with neurological manifestations. The first case was of a 14-year-old boy with no previous history of any comorbidities who presented with bilateral opsoclonus with multifocal spontaneous myoclonus with cerebellar ataxia with a preceding history of fever and acute gastroenteritis. The second case of a 30-year-old gentleman with no previous history of any comorbidities presented to us with generalized tonic-clonic seizures and spontaneous multifocal myoclonus with a preceding history of fever. Both cases had no motor, sensory, cerebellar, or autonomic involvement. The pathophysiology of central nervous system (CNS) infections in scrub typhus is attributed to three major mechanisms of vasculitis, direct invasion, and immune-mediated. CNS involvement in scrub typhus is a significant marker for risk of mortality or morbidity. The most common CNS manifestations in scrub include meningitis, encephalitis, and seizures. Opsoclonus, myoclonus, and parkinsonism are comparatively rare manifestations.Scrub typhus infection must be considered in the differential diagnosis of clinical neurological features with even a remote history of acute febrile illnesses in endemic regions like ours, despite the absence of any eschar, rashes, and unremarkable neuroimaging.

Keywords

Opsoclonus

Myoclonus

Ataxia

Orientia tsutsugamushi

Scrub typhus

Case series

INTRODUCTION

Derived from the word “typhos,” “typhus” indicates a stupor that occurs due to central nervous system (CNS) involvement secondary to inflammation. Predominantly endemic to the Southeast Asian region, scrub typhus is one of the leading causes of infection in India[1] and is on a rising trend. It usually presents as a simple acute febrile illness, often with a rash or an eschar, with few cases complicating to multi-system involvement, one-fifth of which involve the nervous system (Central or peripheral).[2] Approximately, an incidence of 1 million diagnosed new cases and a 100 times more people are prone to develop scrub typhus annually.[3] The most practiced method of laboratory confirmation is serologically, using the indirect fluorescent assay.[4] Being clinically significant but completely treatable, early diagnosis is key to successful treatment.

However, certain times, atypical cases present to us with a rather different systemic manifestation and by an ignored retrospective history or incidental laboratory findings have been diagnosed with scrub typhus and managed, respectively, thereafter, showing complete resolution of symptoms.

Our present article discusses two serial cases that presented to us primarily with spontaneous abnormal movement disorders and were retrospectively diagnosed to be a neurological complication to scrub typhus.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

A 14-year-old boy presented with a history of one episode of high-grade fever associated with chills and rigors, vomiting, and loose stools 3 days back, for which he was treated and completely relieved. Three days later, he developed acute onset abnormal brief shock-like jerky movements of the whole body including the head, associated with tremulousness, present throughout the day, aggravated on sitting or standing, relieved while sleeping. Family members then simultaneously noticed abnormal eye movements, seen intermittently, non-specific in direction, and prominent when trying to focus on some objects in front of him. He, thereafter, in a day developed unsteadiness while walking, in the form tendency to fall on either side with clumsiness in using hands while feeding or navigating foot through chappals.

| Diagnosis | Examination | Investigations | Treatment | Follow-up (after 3 months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Post-infectious opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome [Etiology-scrub typhus] | • Bilateral opsoclonus [Video 1] • Multifocal spontaneous myoclonus [Video 2] • Bilateral cerebellar signs-present (ICARS score-34/100) • Gait: Independent with slow initiation of gait, wide-based, short stance, bouncing-like steps interrupted with jerky movements, and difficulty in turning [Video 3] • Rest general, sensory, and motor system examination – normal |

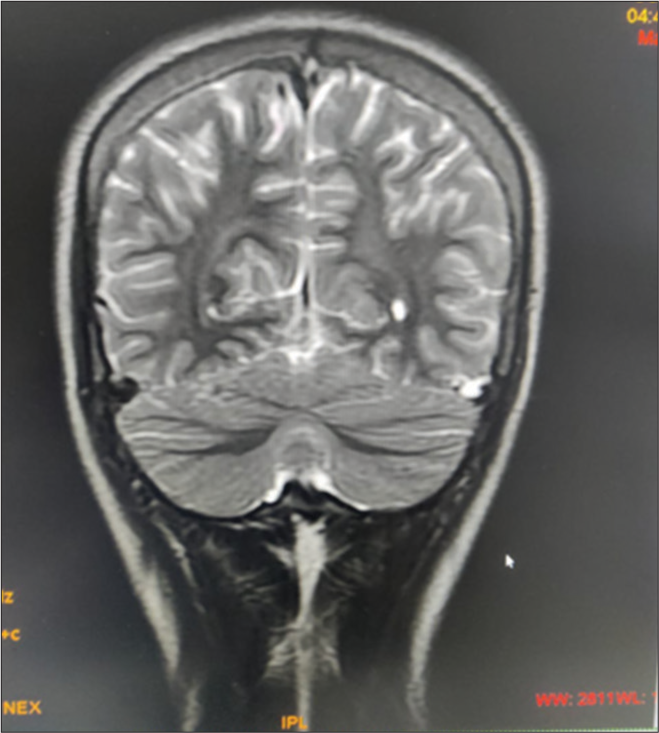

- Scrub typhus IgM Positive with a titer level of 3.4. - CSF pleocytosis with 15 TLCs with 95% lymphocyte - Hemogram, Renal function, Liver function test, - MRI brain-normal [Image 1] |

- Oral Doxycycline for 14 days | - Complete resolution of symptoms - No residual deficit |

| Case 2 | Post-infectious seizure-myoclonus syndrome (Etiology: Scrub typhus) | • Generalized rigidity (MDS-UPDRS Grade II) • Multifocal spontaneous myoclonus [Video 4] • Intentional tremors in his left upper limb • Rest general, sensory, cerebellar system examination-normal |

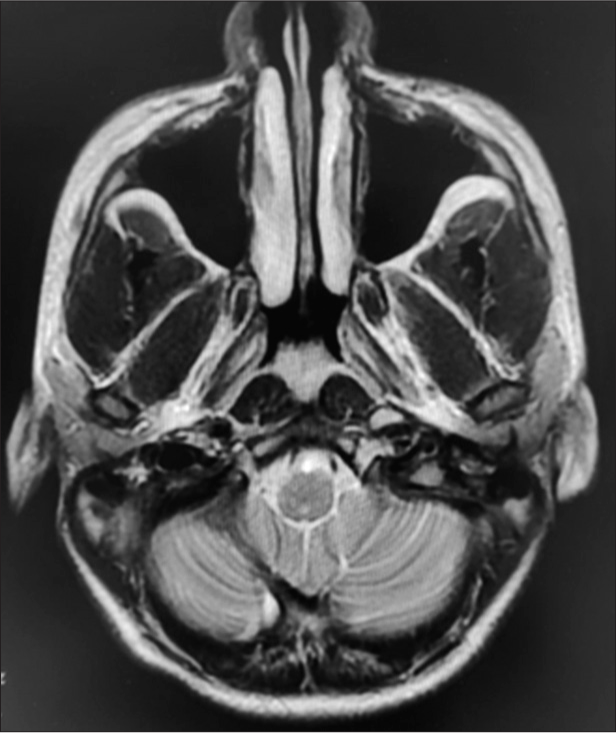

- 2 samples of scrub typhus IgM antibody: positive (sent 1 week apart – Titres 3.1, 3.4 respectively). - Hemogram, renal function, liver function test, CSF examination-Normal - MRI brain normal [Image 2] |

- Oral doxycycline for 14 days - Anti-epileptics for 3 months |

- Complete resolution of symptoms - No residual deficit [Video 5] |

ICARS: International cooperative ataxia rating scale, MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging, CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid, TLC: Total leukocyte count, IgM: Immunoglobulin M, MDS UPDRS: Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale

Video 1:

Video 1:Bilateral opsoclonus (Case 1).Video 2:

Video 2:Spontaneous multifocal myoclonus (Case 1).Video 3:

Video 3:Bouncy gait (Case 1).Video 4:

Video 4:Spontaneous multifocal myoclonus with myokymia (Case 2).Video 5:

Video 5:Follow-up showing complete resolution (Case 2).

- Magnetic resonance imaging brain of the case with opsolconus-myoclonusataxia syndrome.

- Magnetic resonance imaging brain image of the patient with seizure-myoclonus syndrome.

There were no associated speech disturbances, swallowing difficulties, vision or hearing abnormalities, limb weakness, abnormal sensory complaints, altered sensorium, or bowel or bladder complaints. He had no significant past, family, or drug intake history (therapeutic or recreational).

Case 2

A 30-year-old gentleman presented with sudden onset, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, of duration 3–4 min, associated with loss of consciousness lasting 30 min with urinary incontinence, followed by post-ictal confusion for about 10 min. He regained consciousness on his own and he did not receive any particular treatment for the same. Thereafter, the patient and his family noticed abnormal tremulousness for the past 5 days, insidious in onset, non-progressive, present all over his body including his face, associated with trembling of voice, aggravated on movement or speaking, and relief on sleeping. 14 days prior, the patient gave a history of 2–3 episodes of high-grade fever associated with chills and rigors, relieved on medication.

There were no associated swallowing difficulties, vision or hearing abnormalities, limb weakness, abnormal sensory complaints, unsteadiness/imbalance while walking altered sensorium, or bowel or bladder complaints. No history of any previous co-morbidities, similar history in family or any chronic therapeutic or recreational drug intake.

DISCUSSION

CNS involvement in scrub typhus is rare and is considered an important predictor of morbidity and mortality.[5] The most common CNS manifestations in scrub include meningitis, encephalitis, and seizures.[6] Less commonly, stroke, opsoclonus, myoclonus, cerebellar involvement, and parkinsonism can occur.[7] Peripheral nervous system involvement can rarely cause plexopathy, radiculopathy, or neuropathy.[8]

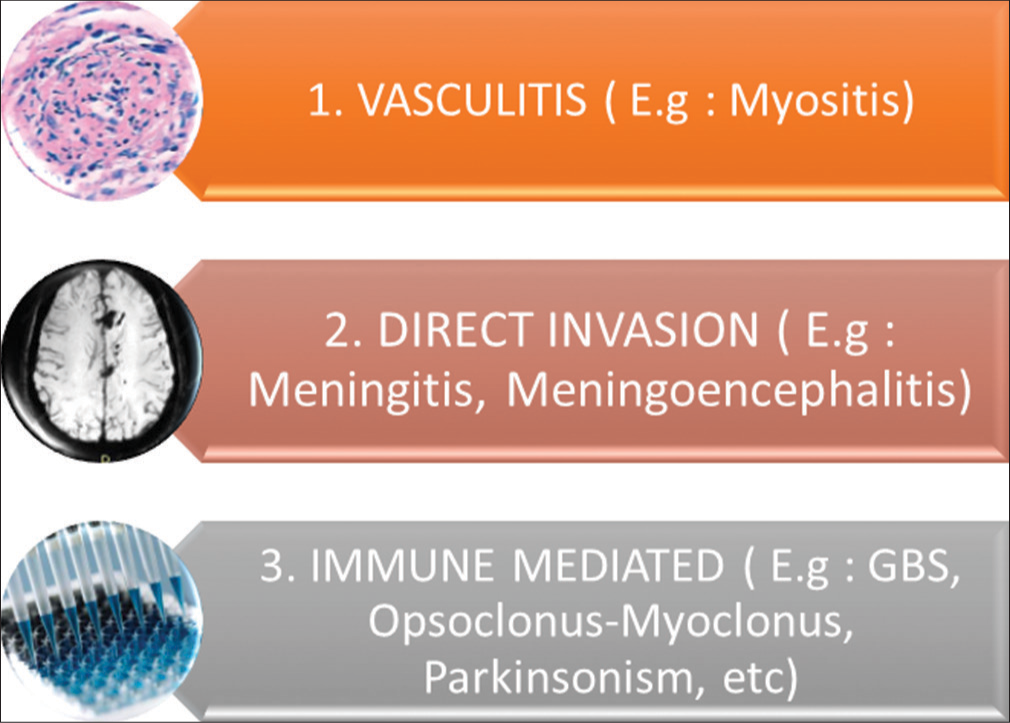

The pathophysiology of CNS infections in scrub typhus is attributed to three major mechanisms: Vasculitis, direct invasion, and immune mediated[9] [Figure 1].

- The three mechanisms hypothesized for neurological manifestations of scrub typhus. GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome.

In both cases, it took an average of 3–5 days from the first episode of fever for neurological features to manifest. Attributing to the involvement of highly vascular bilateral basal ganglia, it was suggestive of the anatomical localization for the movement disorders, pathologically vasculitis, though asymmetrical.

Few unique neurological cases of scrub typhus have been documented. One report suggests scrub typhus causing rapidly progressive cognitive impairment.[10] Another case reports, the development of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome secondary to scrub typhus.[11] A retrospective study was conducted in a 2700-bedded hospital in South India over 5 years. Out of 1650 scrub typhus patients, 18 had opsoclonus (17 presented with opsoclonus, and one developed opsoclonus on the 5th day of admission). It was noted that these CNS symptoms developed at an average of 11 days from fever onset. It was associated with myoclonus in 94% of cases (i.e., 17/18), cerebellar dysfunction in 67% (12/18), and extrapyramidal syndrome in 33% (6/18). The case fatality rate was 5.5% (i.e., 1/18). Complete resolution of all symptoms in surviving patients occurred around 12 weeks post-discharge.[12]

CONCLUSION

Our case series is to appraise practicing neurologists to consider infectious causes for cases presenting with acute movement disorders (hypokinetic/hyperkinetic). Scrub typhus infection must be considered in the differential diagnosis of clinical neurological features with even a remote history of acute febrile illnesses in endemic regions like us (the tropics or subtropics), despite the absence of any eschar, rashes, and unremarkable neuroimaging. Otherwise, this treatable disease may result in multi-organ failure and even death, if diagnosis is delayed.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Videos available on:

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Scrub typhus: A reemerging infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2020;33:365-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurological manifestations of scrub typhus. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2022;22:491-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The burden of scrub typhus in India: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009619.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus serologic testing with the indirect immunofluorescence method as a diagnostic gold standard: A lack of consensus leads to a lot of confusion. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:391-401.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central nervous system involvement in scrub typhus. Trop Doct. 2014;44:36-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickettsial infections of the central nervous system. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007469.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute cerebellar ataxia, acute cerebellitis, and opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:1482-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus associated with central and peripheral nervous system involvement: A rare diagnostic entity. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2022;25:944-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neurological facets of scrub typhus: A comprehensive narrative review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2021;24:849-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case of scrub typhus related encephalopathy presenting as rapidly progressive dementia. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2017;16:83-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): Diagnosis and management. Pract Neurol. 2022;22:183-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrub typhus-associated opsoclonus: Clinical course and longitudinal outcomes in an Indian cohort. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2019;22:153-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]