Translate this page into:

Potential for Increased Epilepsy Awareness: Impact of Health Education Program in Schools for Teachers and Children

Meena Kolar Sridara Murthy, PhD Department of Mental Health Education, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Dr. M.V. Govindaswamy Centre Ground Floor, Hosur Road, Bengaluru-560029, Karnataka India meenaksiyer@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Epilepsy, although a common disorder, yet is highly stigmatized. Under this condition, children with epilepsy are more vulnerable to stigmatization, social isolation, lack of support, and psychological and emotional problems. Thus, there is an immediate need of literature focusing on intervention studies to change the attitudes of school teachers and children.

Methods The study was conducted with the objectives to evaluate knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) about epilepsy among school teachers and children; provide educational training program to teachers; and check the efficacy of training program imparted by teacher and trainer.

Results Repeated measure of analysis of variance shows that knowledge (F = 1,134.875, p < 0.001), attitude (F = 2,429.909, p < 0.001), and practice (F = 2,205.122, p < 0.001) are significantly different between pre- and posttests indicated by Pillai’s trace test. Similarly, from the Pillai’s test, knowledge (F = 49.317, p < 0.001), attitude (F = 125.304, p < 0.001), and practice (F = 178.697, p < 0.001) are significantly different among teachers, trainer imparting training to children, and teachers imparting training to children. It is seen that KAP scores significantly differ between two time points and across the three groups. Among all the groups, teachers imparting training to children had high level of practice.

Conclusion Inclusion of health education programs in the textbooks and health education schemes for teachers and school children are crucial ways to bring a change in their attitude, behavior, and practices toward epilepsy.

Keywords

epilepsy awareness

health education

awareness among teachers

awareness among children

school

intervention

Introduction

Epilepsy is a widely recognized neurological problem that happens because of the disarrangement in the course of action of the nervous system. This happens because of the overabundance and cluttered release from the neurons in the brain resulting in the unsettling influence on sensation leading to loss of responsiveness.1 2 Epilepsy affects around 70 million individuals all over the globe.3 Speaking from the Indian context, epilepsy is the second leading problem to affect the rural and urban population which has made the disorder a public health issue despite being clinically benign in most cases.4

Diagnosis of epilepsy leads to a considerable amount of negative psychological effect especially on school going children as they have to face a lot of discrimination in school environment from their teachers and peers. Although there are studies from the developing countries regarding awareness about epilepsy, a lot of effort is required to clear the misconceptions about the disorder.5 A survey of school teachers done in a developing country like Northwest Nigeria showed that there existed a considerable low level of knowledge and misconceptions related to epilepsy.6 Studies have revealed that a considerable proportion of students and teachers have misconceptions and stigma related to epilepsy that makes a child with epilepsy difficult to get in with the society.7 A study in South India showed that although 88% of people had heard about epilepsy, lack of proper knowledge has created negative attitude toward the disorder, 23% thought that it is hereditary and 23% thought it to be a type of lunacy.8 Due to the lack of awareness, it has been noted that few people do not really know what to do when a person is having an episode of seizure. This further strengthens the belief that epilepsy cannot be treated.9 10

Health educational programs in developed and developing countries have resulted in increased epilepsy knowledge, adherence to treatment methods and drugs, and increased self-esteem among persons with epilepsy.11 12 One of the major problems in the developing countries when it comes to communicable diseases such as epilepsy is the treatment gap which do not reduce just by providing pharmacological medicines. This shows that the existing framework of the health systems is not adequate. An evaluative study on the impact of comprehensive education program on epilepsy was conducted in Chandigarh, India for school teachers. When a comparison was made on the knowledge, skills, and attitude about the first-aid management of epilepsy before and after the program, it showed improvements significantly in different categories.13

In recent times, there exists a dearth in the literature about interventions that could bring a change among school going children about the concept of epilepsy.7 The same hold true for the school teachers too. This is proved by a study done in Riyad that shows that there is a need of increased awareness on epilepsy among teachers in primary school.14 The first step toward planning of an intervention is knowing the attitude of the community and stakeholders toward any disease prior to education. Health education is crucial component of disease control and can be used as an effective tool for mass communication to eradicate myths and misconceptions. With this objective, the present study aims to educate the school teachers and students about epilepsy after evaluating their knowledge, attitude, beliefs, and practices so that a safer environment can be built for children with epilepsy, free from social stigma and misconceptions.

Materials and Methods

The aim of the study was to assess the efficacy of the intervention of a health education program for school teachers and children and test the efficacy of Training of trainers (TOT) program aimed to create awareness among children in school by different groups. The objectives included assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAP) with regard to epilepsy among teachers and children; impart the training to teachers; and check the efficacy of training program imparted by teacher and trainer.

Ethics

The research study was approved by the ethics committee of the institute. Informed consent in writing from teachers and assent from school children were taken.

Study Design

Selection and Description of Participants

The study was conducted among government school teachers and students in Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. The researchers approached Education Department, Government of Karnataka to obtain the permission to conduct the study. After the permission, headmasters were requested to depute the interested teachers for the training program. After the permission, teachers were requested to be a part of a 2-day training program on epilepsy and total 39 teachers from eight schools participated. Once the training was provided to teachers, the teachers were requested to conduct the program in their school. Out of 39 teachers trained by clinician, only 5 teachers conducted the training among 50 children and returned the filled questionnaires. Other teachers could not able to conduct the intervention. The reasons were academic pressure, transferred to other places, were not comfortable to talk about a medical issue, etc.

Again, to match the number of children, the researchers conducted a study among 50 children. A government school was chosen and permit to carry out the intervention research was acquired by the school principal and Education Department, Government of Karnataka.

The researchers imparted health education program to children. Students from ninth grade were eligible for participation from the school. The researchers visited each class and explained about the study and an open invitation had been extended to participate in the study. A notice also had been put on the notice board inviting students to participate in the study. A total of 50 students enrolled for the study. The study took place in four batches, each consisting of 15 to 18 school children. The training program was conducted for 3 days. Notes on the training sessions were made based on the observation. Each session was immediately assessed by taking feedback from the students about their perception of the quality, subject matter and its importance, time period of education sessions, and recommendation for improvements. Post assessments were administered after a month. For ethical reasons, the investigator along with the coinvestigators went back to the schools to carry out a half day workshops for teachers and students of the selected schools. The interventional video was shown. A manual for teachers so created were handed over to the teachers for future reference.

Tool for Data Collection

Evaluation tool for KAP was created by conducting individual interviews with the children on knowledge, attitude, beliefs, and practices based on epilepsy using an interview guide. It was also based on statements from experienced clinician’s on epilepsy awareness and review of literature. The framed instrument was then forwarded to subject experts for face validity. On their recommendations, the tool was modified for the study. The researchers finalized the tool with a case demonstration of child having an episode of seizure to aid understating of seizures better with the developed KAP tool. The students filled the questionnaire and returned to investigator.

Intervention Package

An evaluation of the usually prescribed school course books was made to find out subject matter related to epilepsy. There were chapters describing other disorders such as vitamin deficiencies, rickets, polio, and malaria to name a few. However, none of the reading material had any substance to up-skill the educators and school children about epilepsy. An intervention module was framed by the researchers on the basis of the precedent assessment, targets, and recommendations of health experts. The intervention module had matter covering topics on epilepsy, its awareness based on the attitude and knowledge of the students, false beliefs related to the disorder, first aid that can be provided, as well as the practices related to epilepsy and what students can do in school when one of their classmates have an episode of seizure. The intervention module also included Information Education Communication (IEC) material which was framed by the researchers to provide a comprehensive health education program. A video of 12 minutes was prepared on first aid that can be provided to a person with epilepsy by the researchers after suitable approval of script. This particular video was shot in the premises of a school, not selected for providing intervention. Informed consent was taken from the school head, interested students and teachers who volunteered to act were chosen for the video. A brief workshop of half a day was conducted to train them as to how they can help in developing the video. A script was developed and validated among subject experts. The script narrated a story of a 13-year-old boy, who is playing cricket with his friends. He has an episode of seizure and how the teacher demonstrates the first aid that could be given to the student. The video had captions and at the end, the key points of how to provide the basic first aid was stressed on. It also cleared the myths and misconceptions that the society or public follow when they see a person having seizure; for example: giving a bunch of keys thinking it will stop the seizure. Additionally, posters aiming to create an awareness about the disorder thereby clearing the false beliefs were made by the researchers to be used for training. In addition to this, group activities and role plays were prepared as a part of the module. The developed intervention program was given to the experts from the field of health education and neurology for face and content validation. The research study additionally made efforts in including education on epilepsy in the regular syllabus for school children by educators. A manual for teachers that was prepared by the researchers was a comprehensive guide which covered the topics given in Table 1.

|

Sl. no. |

Topics |

|---|---|

|

1 |

Introduction to epilepsy |

|

2 |

How to tell the difference between one type of seizure and another? |

|

3 |

What can trigger a seizure? |

|

4 |

Do I need to call an ambulance? |

|

5 |

How to respond to a seizure? |

|

6 |

Are there side effects with antiepileptic drugs? |

|

7 |

Effects on learning |

|

8 |

How teachers can help—video show? |

|

9 |

Epilepsy checklist at a glance |

The same manual was used to train the teachers in TOT and the trainer also used while training children.

Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20.

Results

Table 2 shows the total sample size of the research study. Out of the 39 government teachers who were trained, around 25% had passed school, while the rest 75% were graduates. When it comes to the children, there were two categories, one in which the trained teachers imparted training to some children and the other in which the researchers imparted training to children. Both the categories had 50 children, all from ninth grade. Numbers of boys were more which are 30 and 35, respectively, for both the groups when compared with girls which are 20 and 15, respectively. A total of 65 boys and 35 girls participated in the study (Table 3).

|

Category |

Group |

Number of participants |

Educational qualification |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviation: PUC, pre-university course. |

|||||

|

Teachers |

Trainer training to teachers |

10 |

PUC passed (12th grade) |

39 |

|

|

29 |

Graduates |

||||

|

Children |

Teachers imparted training to children |

Boys |

Girls |

9th grade |

50 |

|

30 |

20 |

||||

|

Researchers imparted training to children |

35 |

15 |

9th grade |

50 |

|

|

Total (N) |

139 |

||||

|

Group |

N |

Pretest |

Posttest |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

|||||

|

Researchers imparted training to children |

50 |

36.58 |

3.44 |

46.66 |

5.32 |

|

Trainer training to teachers |

39 |

37.51 |

3.42 |

50.74 |

3.74 |

|

Teachers imparted training to children |

50 |

34.22 |

2.25 |

54.06 |

3.35 |

|

Total |

139 |

35.99 |

3.34 |

50.47 |

5.28 |

After performing the repeated measure of analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pillai’s trace test was used to arrive at the inference based on Mauchly’s test. It is inferred that knowledge is significantly different between pre- and posttests (F = 1,134.875, p < 0.001) as indicated by Pillai’s trace test. Similarly, from the Pillai’s test, knowledge is also significantly different (F = 49.317, p < 0.001) among the three groups. Therefore, we conclude that knowledge scores significantly differ between two time points and across the three groups. Further, we can observe the changes in the line graph shown (Fig. 1). It shows that in the preassessment, all the three groups had similar level of knowledge (line 1), but after the intervention, it had increased significantly (line 2). Among all the groups, teachers imparting training to children had high level of knowledge (Table 4).

|

Group |

N |

Pretest |

Posttest |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

|||||

|

Researchers imparted training to children |

50 |

42.28 |

5.05 |

57.12 |

5.26 |

|

Trainer training to teachers |

39 |

38.92 |

6.60 |

67.35 |

3.21 |

|

Teachers imparted training to children |

50 |

38.90 |

3.09 |

72.48 |

2.59 |

|

Total |

139 |

40.12 |

5.20 |

65.52 |

7.69 |

-

Fig. 1 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of knowledge of different categories.

Fig. 1 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of knowledge of different categories.

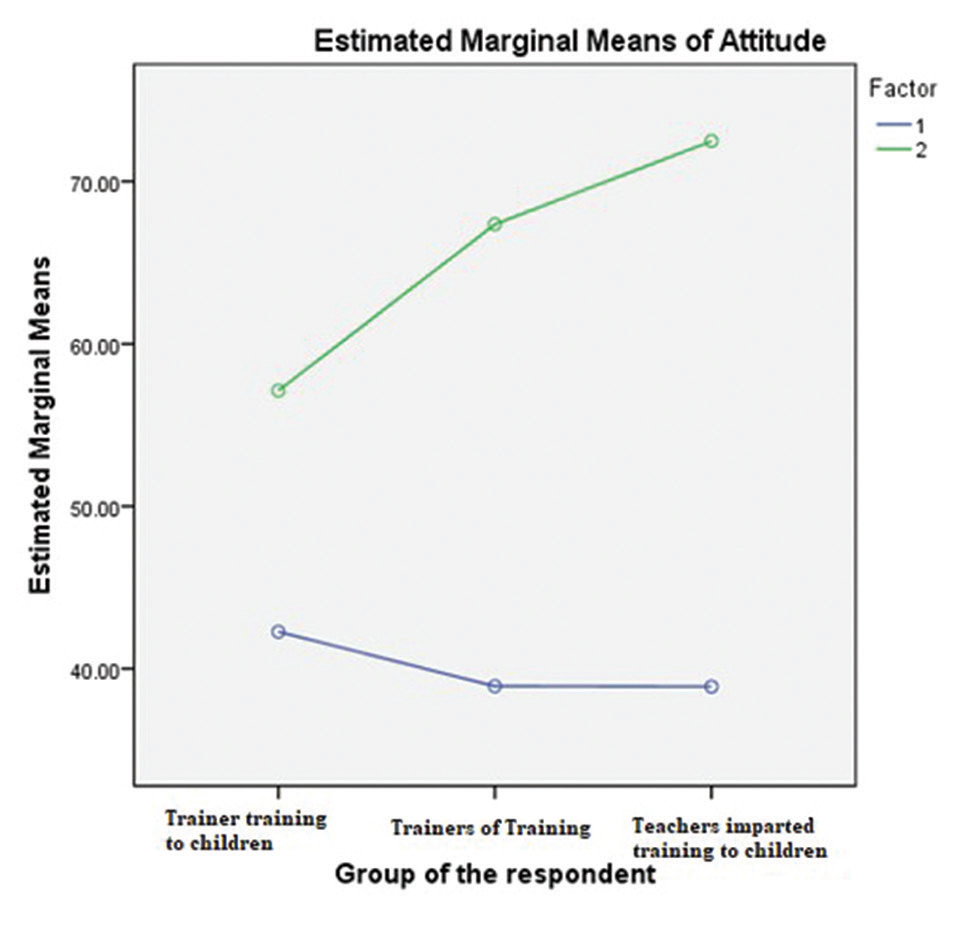

After performing the repeated measure of ANOVA, Pillai’s trace test was used to arrive at the inference based on Mauchly’s test. It is inferred that attitude is significantly different between pre- and posttests (F = 2,429.909, p < 0.001) as indicated by Pallai’s trace test. Similarly, from the Pillai’s test, attitude is also significantly different (F = 125.304, p < 0.001) among the three groups. Therefore, we conclude that attitude scores significantly differ between two time points and across the three groups. Further, we can observe the changes in the line graph shown (Fig. 2). It shows that in the preassessment, all the three groups had similar level of attitude (line 1), but after the intervention, it had increased significantly (line 2). Among all the groups, teachers imparting training to children had high level of attitude (Table 5).

|

Group |

N |

Pretest |

Posttest |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

||

|

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

|||||

|

Researchers imparted training to children |

50 |

41.16 |

4.35 |

65.14 |

5.95 |

|

Trainer training to teachers |

39 |

50.18 |

6.57 |

66.69 |

12.47 |

|

Teachers imparted training to children |

50 |

38.10 |

3.56 |

81.18 |

2.22 |

|

Total |

139 |

42.59 |

6.89 |

71.34 |

10.59 |

-

Fig. 2 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of attitude of different categories.

Fig. 2 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of attitude of different categories.

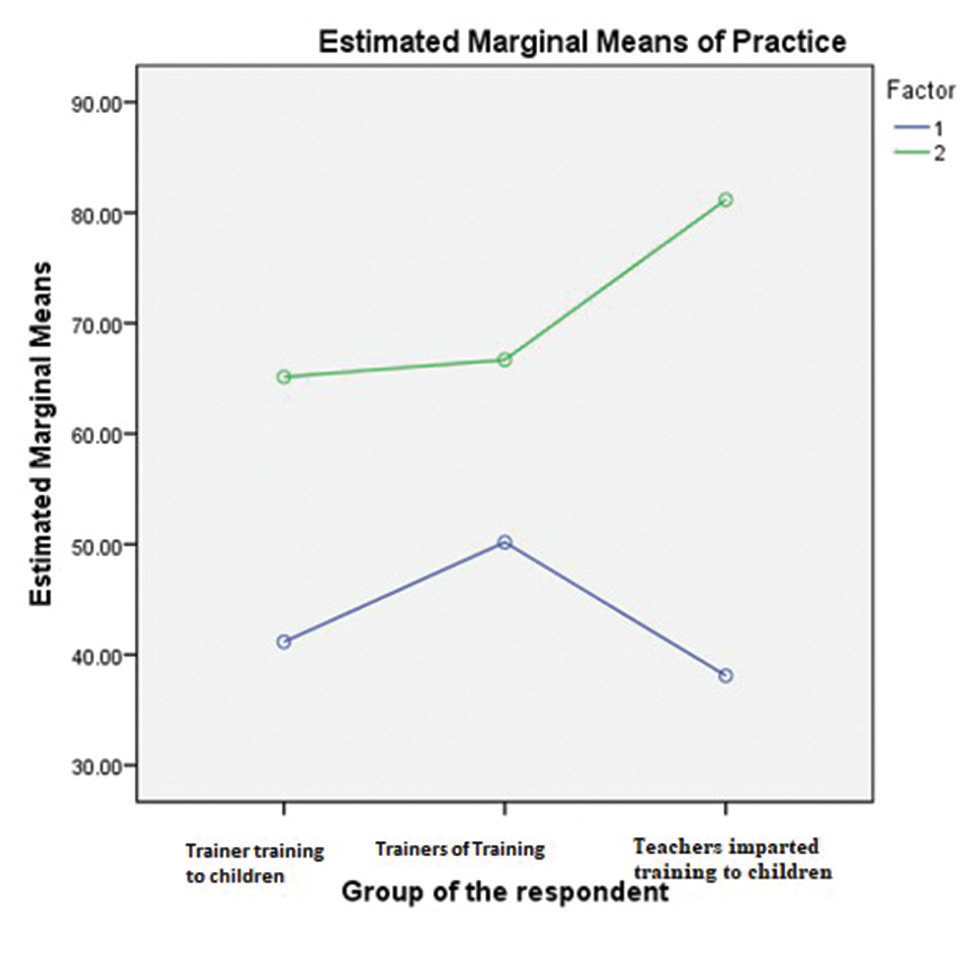

After performing the repeated measure of ANOVA, Pillai’s trace test was used to arrive at the inference based on Mauchly’s test. It is inferred that practice is significantly different between pre- and posttests (F = 2,205.122, p < 0.001) as indicated by Pallai’s trace test. Similarly, from the Pillai’s test, practice is also significantly different (F = 178.697, p < 0.001) among the three groups. Therefore, we conclude that practice scores significantly differ between two time points and across the three groups. Further, we can observe the changes in the line graph shown (Fig. 3). It shows that in the preassessment, all the three groups had similar level of practice (line 1), but after the intervention, it had increased significantly (line 2). Among all the groups, teachers imparted training to children had high level of practice.

-

Fig. 3 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of practice of different categories.

Fig. 3 Graphical representation of estimated marginal means of practice of different categories.

Discussion

The present study compared the efficacy of the intervention of a health education program among three groups in school, that is, researchers imparted training to children, Training of trainers ( TOT), and teachers imparted training to children. Various studies have shown that epilepsy is a common disorder which affects large people around the globe.3 In India, it is a second leading public health problem which is leading to stigmatization, social isolation, psychological effect, and cultural barriers. When it comes to creating an awareness about epilepsy, teachers play a very important role in bringing down the stigma. If provided with proper education about epilepsy, teachers can play a very crucial role in bringing down stigma, discrimination, social isolation that students face when they have an episode of epileptic seizures in school.1 3 Hence, there is a need to study the efficacy of the training programs on epilepsy. Increased knowledge has always brought about a change in attitude and practices among people toward epilepsy and people suffering from the same. The present study assessed the textbooks of the school and found that no textbooks had basic information at all about epilepsy to bring about an awareness among students and teachers. This was further stressed by studies reporting that in developing countries and in India, textbooks are not having the content of the epilepsy.7 13

In the first level, TOT workshop was conducted on KAP. In the baseline, teachers had limited knowledge and had negative attitude. They reported to have faulty practices and beliefs, such as “Epilepsy is not curable and due to past sin a person would suffer from this ailment.” After the intervention, 1 month later, assessment shows that teacher’s knowledge has increased significantly and attitude and practices also changed significantly. During the follow-up, one teacher reported that “one student had seizure in my class and I was confident to handle the situation. After he regained the memory, I enquired about his medication compliance and found that he was irregular on medicines. I called his parents and counseled them about the need of regular medicines and follow-up with the treating doctor.”

In the similar way, the same modules were introduced to the children by the trainer and some trained teachers. It shows that there is a difference between pre- and post assessments in all three groups and also among the groups on KAP. After the intervention, KAP has changed significantly. In the training imparted by the researcher and teachers to children shows that teachers imparted training showed more KAP than imparted by trainer. This demonstrates that teachers’ training is more effective than trainer’s. Hence, training the teachers and imparting to children is found to be beneficial. Studies show that during the young age, students listen and follow teachers’ instructions than others’. Hence, training teachers and including a module or manual would empower them with the correct knowledge of first aid in epilepsy, which will further aid the students to help their peers having an episode of seizure. Including a module in the textbooks would bring down the stigmatization, encourages socialization, decrease the cultural barriers, self-esteem.

The results also show that teachers’ knowledge has changed significantly from pretest to posttest. Though studies report teachers had limited knowledge on epilepsy, they were not free from stigma6 and negative attitude; wrong beliefs that epilepsy is a heredity disorder were present.9

Conclusion

The review shows that there are not many studies conducted on impact of a health education program for epilepsy awareness among school teachers and children. This is a first study conducted to assess the impact of teachers imparted training to children. As review shows that current school-based curriculum is not having any information on epilepsy, and its causes and first aid measures in their syllabus, children and teachers are having lack of knowledge on epilepsy. The present study justifies that training imparted by teachers to students was extremely effective. If teachers can be trained and empowered with correct knowledge about epilepsy and useful first aid measures, they can be a key stakeholder to bring down the stigma among students. Not only this, they can also educate the parents and others associated with the students. It would also be of significant help to other stakeholders such as the Education Departments who take this up and actively introduce a module on epilepsy and its basic interventions that can be easily provided along with other disorders which are already covered.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Knowledge, attitude and beliefs about epilepsy among adults in a northern Nigerian urban community. Annals of African Medicine. 2005;4(3):107-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familiarity with, understanding of, and attitudes toward epilepsy among people with epilepsy and healthy controls in South Korea. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;16(2):260-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the differences in prevalence of epilepsy in tropical regions. Epilepsia. 2011;52(8):1376-1381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lahoti N. 11 Troublesome Myths about Epilepsy. Available at: https://www.practo.com/healthfeed/11-troublesome-myths-about-epilepsy-12703/post. Accessed January 31, 2019

- Epilepsy familiarity, knowledge, and perceptions of stigma: report from a survey of adolescents in the general population. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3(4):368-375.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epilepsy and education in developing countries: a survey of school teachers’ knowledge about epilepsy and their attitude towards students with epilepsy in Northwestern Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:255.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of a school-based health education program for epilepsy awareness among schoolchildren. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;57:77-81. Pt A

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude, and practice of people toward epilepsy in a South Indian village. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7(3):374-380.

- [Google Scholar]

- High school students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice with respect to epilepsy in Kerala, southern India. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;9(3):492-497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life of people with epilepsy: a European study. Epilepsia. 1997;38(3):353-362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the impact of comprehensive epilepsy education programme for school teachers in Chandigarh city, India. Seizure. 2014;23(1):41-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary school female teachers’ knowledge, attitude, and practice toward students with epilepsy in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(2):331-336.

- [Google Scholar]