Translate this page into:

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome with PLEDs-plus due to mesalamine

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ajith Cherian, Department of Neurology, Government Medical College, Trivandrum, Kerala, India. E-mail: drajithcherian@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A 32-year-old lady developed status epilepticus and acute visual loss while on mesalamine for Crohn's disease. Her clinical course and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were suggestive of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). She had periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges plus (PLEDs-plus) on electroencephalogram (EEG), which responded to sodium valproate. Her vision improved from counting fingers at one-meter distance to 6/12. Though different cytotoxic drugs have been implicated as causative agents, this is the first case report of mesalamine-induced PRES. This case highlights the need for aggressive treatment of PLEDs-plus with EEG monitoring using a broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug like valproate, which has contributed to the rapid reversibility of vision in PRES subjects, and the need for a thorough drug history for etiological clues.

Keywords

Acute blindness

Crohn's disease

RPLE

status epilepticus

valproate

Introduction

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinicoradiologic syndrome with seizures, visual loss, headache, and altered sensorium. As the name suggests, the clinical and radiological features are usually reversible. A diverse array of trigger factors, including accelerated hypertension, eclampsia, medications such as cyclosporineand antineoplastic agents, severe hypercalcemia, thrombocytopenic syndromes, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, amyloid angiopathy, and systemic lupus erythematosus, can lead to a pathophysiological process that ends in leakage of the blood-brain barrier causing vasogenicedema and PRES.[1] To date, mesalamine has never been reported as an etiological cause for PRES.

Case Report

A 32-year-old lady presented with convulsive status epilepticus, altered sensorium, andacute-onset visual loss of counting fingers at one-meter distance. Optic fundi were normal, pupillary reactions brisk, and plantar responses were bilaterally extensor. She had a history of Crohn's disease diagnosed 11 years prior to presentation and was on mesalamine (5-amino salicylic acid) 400 mg twice daily. She had sputum-positive pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) detected four years prior, which was multidrug resistant, andshe was on ethionamide, high-dose ethambutol, cycloserine, and levofloxacin daily. Two months prior to current admission, she had an exacerbation of diarrhea, and colonoscopy showed extensive linear ulceration with cobble stoning in the rectumand transverse and ascending colon. Biopsy showed mixed inflammatory infiltrate and noncaseatinggranulomaof colonic mucosa, consistent with Crohn's disease exacerbation. Her mesalamine dose was doubled to 800 mg twice daily since then.

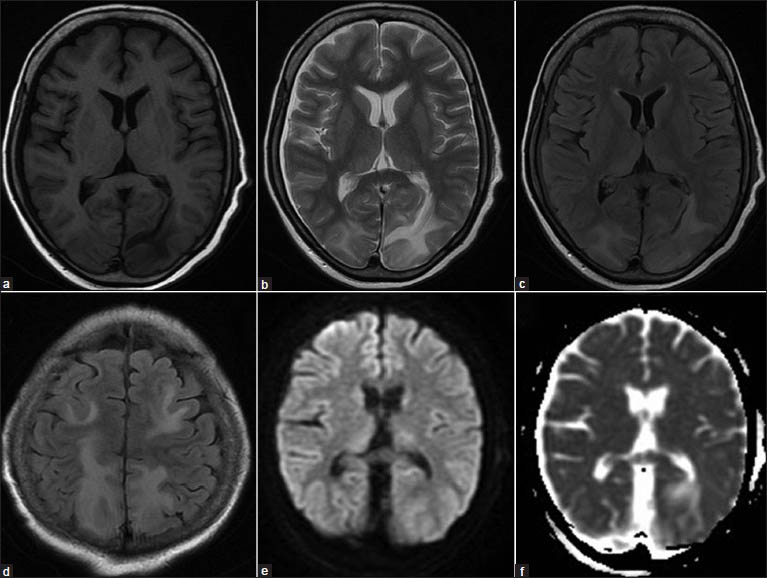

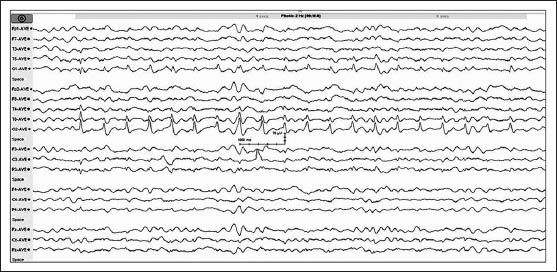

On current admission, her cerebrospinal fluid study and vasculitic profile were normal, and viral markers including hepatitis B antigen, retro, and hepatitis C virus were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the brain showed hypodensity in bilateral parieto-occipital subcorticalregions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain [Figure 1] showed T1 hypointense, T2, and FLAIR (FLAIR: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) hyperintense lesions in bilateral parieto-occipital (left > right) and frontal regions without contrast enhancement. Lesions showed no diffusion restriction and were suggestive of PRES. Electroencephalogram (EEG) [Figure 2] showed medium amplitude 3-4 Hz delta and slow theta activity which was generalizedalong with periodic short-interval (0.75 Hz) sharp waves of 100-150 μV amplitude over the right occipital region. There were small-amplitude sharp wave discharges of ~50 μV amplitude superimposed over the after-coming slow waves, giving a PLEDs-plus morphology. On admission, the patient was loaded with valproate for status epilepticus, and it was continued parenterally with follow-up EEG monitoring till the PLEDS-plus subsided. The second EEG of the patient showed disappearance of the PLEDs-plus morphology. But intermittent photic stimulation at low frequency showed grade III photoparoxysmal response (PPR) from bilateral occipital regions (right > left), although the background activity remained the same [Figure 3]. The third EEG of the patient showed disappearance of the PLEDs-plus morphology and PPR. The patient improved clinically with no further seizures, and visual acuity improved to 6/12. The clinical improvement in vision correlated with the electrical resolution of posterior head region PLEDs-plus, which evolved rapidly over three days with parenteral valproate therapy. Mesalamine, given for Crohn's disease, was thought to be the offending drug causing PRES; this was therefore stopped and replaced by steroids.

- (a) T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing hypointensities in bilateral parieto-occipital regions, left more than right, (b) T2-weighted and, (c) FLAIR images (FLAIR: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) showing hyperintensities in the same region, (d) FLAIR images showing bilateral frontal and parietal hyperintensities, (e) Diffusion weighted and, (f) Apparent diffusion coefficient images showing no restriction suggestive of vasogenic edema

![Initial electroencephalogram (EEG) of the patient on admission showed periodic short-interval (0.75 Hz) sharp waves [periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs)] of 100-150 μV amplitude over the right occipital region with medium-amplitude delta and slow theta activity, which was generalized. There were small-amplitude sharp wave discharges of ~ 50 μV amplitude (arrow) over the after-coming slow waves giving a PLEDs-plus morphology](/content/150/2014/5/1/img/JNRP-5-72-g002.png)

- Initial electroencephalogram (EEG) of the patient on admission showed periodic short-interval (0.75 Hz) sharp waves [periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs)] of 100-150 μV amplitude over the right occipital region with medium-amplitude delta and slow theta activity, which was generalized. There were small-amplitude sharp wave discharges of ~ 50 μV amplitude (arrow) over the after-coming slow waves giving a PLEDs-plus morphology

- Second electroencephalogram (EEG) of the patient after giving valproate showed disappearance of periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs). Intermittent photic stimulation at low frequency showed grade III photoparoxysmal response (PPR) from bilateral occipital regions (right > left), although the background activity, which consisted of generalized medium-amplitude delta and slow theta activity

Discussion

PRES presents acutely with multiple seizures, headache, vomiting, altered sensorium, and visual disturbances with MRI features of symmetric or asymmetric vasogenic edema affecting preferably the parieto-occipital regions of the brain.[2] Predilection of lesions for the posterior parieto-occipital regions is thought to be due to the paucity of sympathetic innervations of the vertebrobasilar system compared with the carotid system.[3] The exact pathophysiology of PRES is still unproven. Both hypoperfusion and hyperperfusion have been implicated. One plausible mechanism isimpaired autoregulationcausingdilatation of cerebral arterioles, with opening up of endothelial tight junctions and leakage of plasma and red cells into the extracellular space, producing edema in the extracellular space. Another mechanism is immune-mediated pathology.[4]

PRES often occurs associated with hypertension, pre-eclampsia, collagen vascular disorders, and adrenal failure. Our patient had a normal blood pressure throughout the course, and her vasculitic workup and all chronic viral markers were negative. The drugs implicated in PRES include immunomodulators like cyclosporine, tacrolimus, cytarabine, azathioprine, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and methotrexate. Drugs may cause an acute toxic insult with axonal swellingand reversible ischemia due to raised endothelin concentrations and damage the blood–brain barrier. Immune-mediated reversible encephalopathy results from T-cell, monocyte–macrophage activation and eventual cytokine expression.[5] Mesalamine (5-ASA) also called 5-amino salicylic acid is an immunomodulator used in inflammatory bowel disease. It acts via inhibitionof the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which inturn modulates the matrix metalloproteinaseand downregulates the antiangiogenic factors endostatin and angiostatin, leading to an increase in angiogenic factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).[6] Horbinski et al. havedemonstrated VEGF increase, endothelial activation, and T-cell trafficking in a patient with PRES, following solid organ transplantation.[7] Thus mesalamine, an immunomodulator, which increases VEGF level, may be directly associated with PRES. So, the most plausible etiological agent of PRES in our patient was mesalamine, and this is the first case report of mesalamine-induced PRES to the best of our knowledge. Mesalamine is widely used in inflammatory bowel disease, and this case report highlights a rare side effect of this drug. We presume that the recent doubling of the dose of mesalamine may have contributed to the insult.

The EEG in PRES varies from normal to nonspecific abnormality with diffuse slowing, focal δ waves, and rare focal sharp waves, especially in the parieto-occipital and temporal regions in association with their abnormal imaging findings.[8] Our patient had the typical clinical and imaging features of PRES, and the EEG showed PLEDs-plus pattern, which evolved to grade IIIPPR at low frequency, which subsided later. Though PLEDs have been described earlierin PRES,[9] neither PLEDs-plus pattern nor PPR has been documented to be associated with it.

In PRES, the damage is more to white than gray matter. Acutely injured neurons in PRES remain viable and even become abnormally excitable. A possible consequence of electrical coupling is the rapid and efficient electrotonic spread of paroxysmal burst discharges from cell to cell, thus facilitating synchronous bursting within a pool of neurons.[10] The EEG correlate would be epileptiform discharges, and periodic synchronous bursting will occur if a burst in one cell is capable of inducing bursting in neighboring cells. Relative integrity of the cortex is critical for the appearance of these complexes as in PRES where the damage is more to white than gray matter. This leads to a state of acute deafferentation of the cortex leading to the formation of PLEDs, which are usually transitory and self-limiting.[11]

This case calls for aggressive treatment of PLEDs-plus with EEG monitoring, where indicated, using a broad-spectrum antiepileptic drug like valproate, which contributed to the rapid reversibility of vision in the present case, and the need for a thorough drug history for etiological clues.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: Incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:904-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:222-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy-related posterior reversible leukoencephalopathysyndrome. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5:163-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, part 2: Controversies surrounding pathophysiology of vasogenic edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1043-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy induced reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:459-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesalamine restores angiogenic balance in experimental ulcerative colitis by reducing expression of endostatin and angiostatin: Novel molecular mechanism for therapeutic action of mesalamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:1071-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible encephalopathy after cardiac transplantation: Histologic evidence of endothelial activation, T-cell specific trafficking, and vascular endothelial growth factor expression. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:588-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status epilepticus as initial manifestation of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. Neurology. 2007;69:894-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges: An initial electrographic pattern in reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2008;42:55-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges in fulminant form of SSPE. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36:524-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges in infants and children. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:47-50.

- [Google Scholar]