Translate this page into:

Not only the Sugar, Early infarct sign, hyperDense middle cerebral artery, Age, Neurologic deficit score but also atrial fibrillation is predictive for symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Address for correspondence: Dr. Sombat Muegtaweepongsa, Thammasat University, Rangsit Campus, Paholyothin Road, Pathum Thani 12120, Thailand. E-mail: sombatm@hotmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) is the most unwanted adverse event in patients with acute ischemic stroke who received intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (i.v. rt-PA). Many tool scores are available to predict the probability of sICH. Among those scores, the Sugar, Early infarct sign, hyperDense middle cerebral artery, Age, Neurologic deficit (SEDAN) gives the highest area under the curve-receiver operating characteristic value.

Objective:

We aimed to examine any factors other than the SEDAN score to predict the probability of sICH.

Methods:

Patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with i.v. rt-PA within 4.5 h time window from January 2010 to July 2012 were evaluated. Compiling demographic data, risk factors, and comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation (AF), ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, previous stroke, gout, smoking cigarette, drinking alcoholic beverage, family history of stroke, and family history of ischemic heart disease), computed tomography scan of patients prior to treatment with rt-PA, and assessing the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score for the purpose of calculating SEDAN score were analyzed.

Results:

Of 314 patients treated with i.v. rt-PA, there were 46 ICH cases (14.6%) with 14 sICH (4.4%) and 32 asymptomatic intracranial hemorrhage cases (10.2%). The rate of sICH occurrence was increased in accordance with the increase in the SEDAN score and AF. Age over 75 years, early infarction, hyperdense cerebral artery, baseline blood sugar more than 12 mmol/l, NIHSS as 10 or more, and AF were the risk factors to develop sICH after treated with rt-PA at 1.535, 2.501, 1.093, 1.276, 1.253, and 2.492 times, respectively.

Conclusions:

Rather than the SEDAN score, AF should be a predictor of sICH in patients with acute ischemic stroke after i.v. rt-PA treatment in Thai population.

Keywords

Acute ischemic stroke

atrial fibrillation

intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Sugar

Early infarct sign

hyperDense middle cerebral artery

Age

Neurologic deficit score

symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage

Thai patients

Introduction

Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH) is the most unwanted adverse event in patients with acute ischemic stroke who received intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (i.v. rt-PA) and is usually associated with unfavorable outcomes. Definitions of sICH in major influential studies including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders Stroke (NINDS) Study, European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) II/III and Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke (SITS) Study are different.[2345] However, the definition used in ECASS II/III study gains the highest inter-rater agreement.[6] The definition of sICH in ECASS II/III is “clinical deterioration causing an increase in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) of ≥ 4 points and whether the hemorrhage was likely to be the cause of the clinical deterioration.”[3] The rate of sICH in Thai population according to ECASS II/III criteria is around 2–6%.[78910]

Many tool scores are available to predict the probability of sICH after i.v. rt-PA including the hemorrhage after thrombolysis (HAT) score,[11] the Multicenter Stroke Survey (MSS) score,[12] the Sugar, Early infarct sign, hyperDense middle cerebral artery, Age, Neurologic deficit (SEDAN) score,[13] the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke (SITS)-sICH score,[14] and the Glucose at presentation, Race (Asian), Age, Sex (male), Systolic blood Pressure at presentation, and Severity of stroke at presentation (GRASPS) score.[15] Among those scores, the SEDAN gives the highest area under the curve-receiver operating characteristic value of 0.77.[16]

We aimed to examine any factors other than the SEDAN score to predict the probability of sICH per ECASS II/III criteria in our center.

Methods

Patients

Thammasat University Hospital is a 460-bed hospital with a stroke unit. The acute stroke service with integrated referral network was established in October 2007. There were two major pathways for the acute stroke patients to achieve the acute stroke system: Referred from outside hospitals of acute stroke network or walk-in. A total of 314 patients were treated with i.v. rt-PA within 4.5 h time window from January 2010 to July 2012.

Definition

sICH is defined as clinical deterioration causing an increase in the NIHSS score of ≥4 points and if the hemorrhage was likely to be the cause of the clinical deterioration (per the ECASS, II).

Early infarct signs include hypoattenuation comprising < 1/3 of middle cerebral artery or other areas which was the cause of ischemic stroke or obscuration of the lentiform nucleus or loss of insular ribbon or obscuration of the Sylvian fissure or cortical sulcal effacement.

Statistical analysis

Data were recorded in a computer with Microsoft excel, analyzed with software SPSS version 18.0 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA), and data of the participating patients were kept confidentially in accordance with the rule of Human Research Ethics committee. The variables of this study had the form of continuous variables and discrete variables. Compiling demographic data, risk factors and comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation [AF], ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, previous stroke, gout, smoking cigarette, drinking alcoholic beverage, family history of stroke, and family history of ischemic heart disease), computed tomography (CT) scan of patients prior to treatment with rt-PA, and assessing NIHSS score for the purpose of calculating SEDAN score were collected with descriptive statistics. Patients were divided into three groups including sICH, asymptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (AsICH), and no intracerebral hemorrhage (NoICH). Univariate associations of parameters in SEDAN score and other significant factors among groups were evaluated by Pearson's Chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression model was performed for calculating the value of absolute risk, odds ratio, and 95% confidence interval of each parameter. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 18.0 for studying the relation of variables by using linear regression for correlation at the significant level of P < 0.05.

Results

Of 314 patients treated with i.v. rt-PA, there were 268 (85.3%) infarct location cases in anterior circulation and 46 (14.6%) cases in posterior circulation. There were 46 ICH cases (14.6%) with 14 sICH (4.4%) and 32 AsICH cases (10.2%), as shown in Figure 1.

- Study flow

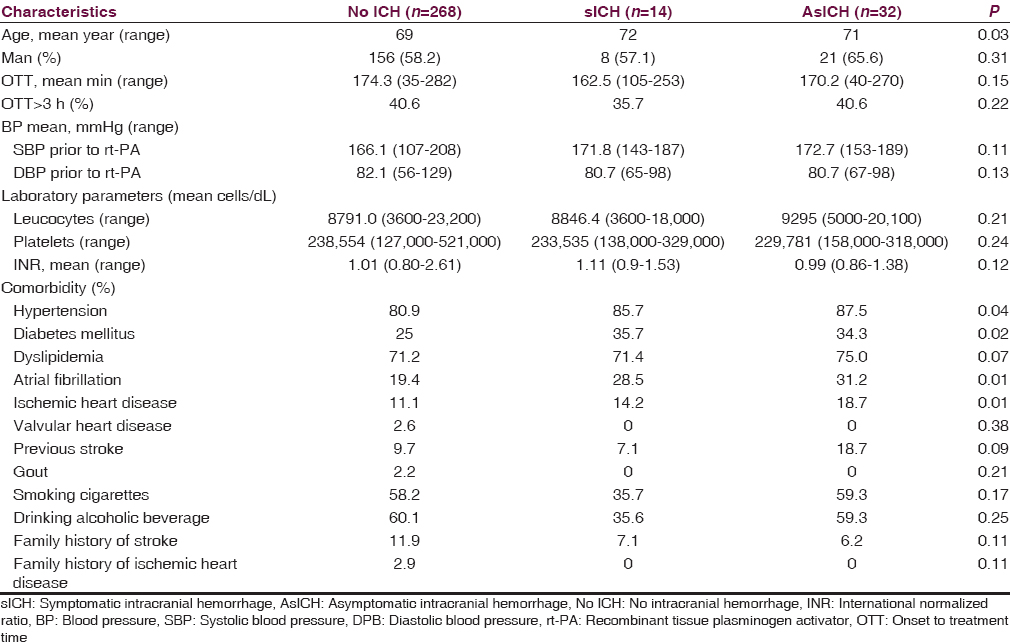

The average age of NoICH, sICH, and AsICH was 69, 72, and 71 years, respectively. Patients in sICH group were statistically significantly older than those in NoICH group. Diabetes, AF, and ischemic heart disease were more found in patients with ICH. Baseline characteristics of our population are shown in Table 1.

Univariate evaluation of each parameter in SEDAN score shows the following:

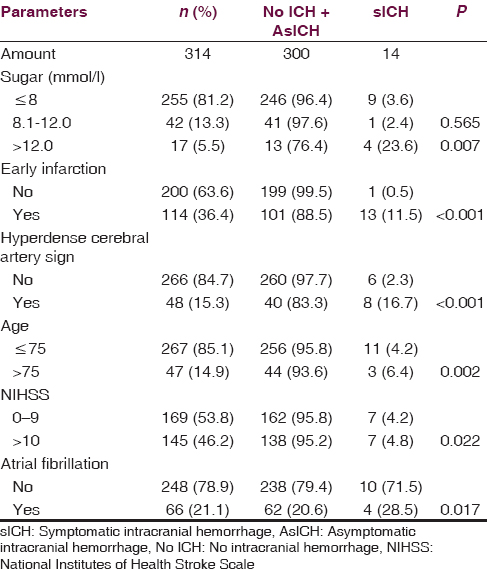

-

Three tiers of baseline blood sugar (continuous variables) consist of ≤ 8, 8.1–12, and >12 mmol/l. From 14 patients with sICH, nine patients had baseline blood sugar ≤ 8 mmol/l and one patient had baseline blood sugar between 8.1 and 12 mmol/l. From 300 patients without sICH, 246 patients had baseline blood sugar ≤8 mmol/l and 41 patients had baseline blood sugar between 8.1 and 12 mmol/l. There was no significant difference between sICH and without sICH for the sugar level at ≤ 8 and 8.1– 12 mmol/l. Considering the sugar level > 12 mmol/l, there were four out of 14 patients with sICH while there were 13 out of 300 patients without sICH. There was a significant difference between sICH and without sICH for the sugar level at >12 mmol/l with P = 0.007

-

From 14 patients with sICH, 13 of them had early infarction (discrete variables) in the initial CT brain. While, from 300 patients without sICH, 101 of them had early infarction. There was a significant difference between sICH and without sICH for early infarction in initial CT brain with P < 0.001

-

From 14 patients with sICH, eight of them had hyperdense cerebral artery sign (discrete variables) in initial CT brain. While, from 300 patients without sICH, forty of them had this sign. There was a significant difference for hyperdense cerebral artery sign (discrete variables) in initial CT brain with P < 0.001

-

From 14 patients with sICH, three of them were more than 75 years old (continuous variables). While, from 300 patients without sICH, 44 of them were more than 75 years old. There was a significant difference for age more than 75 years with P = 0.002

-

From 14 patients with sICH, seven of them had initial NIHSS as 10 or more (continuous variables). While, from 300 patients without sICH, 138 of them had initial NIHSS as 10 or more. There was a significant difference for initial NIHSS as 10 or more with P = 0.022

-

From 14 patients with sICH, four of them had AF (discrete variables). While, from 300 patients without sICH, 62 of them had AF. There was a significant difference for AF (discrete variables) with P = 0.017.

The univariate evaluation is shown in Table 2.

The rate of sICH occurrence was increased in accordance with the increase in the SEDAN score in our study. The SEDAN score was ranking from 0 to 6 points. All 93 patients with 0 point showed no sICH or AsICH at all. While the only one patient with 6 point had sICH. The rate of sICH was correlated with increasing total score: 0% at total score 0, 3.3% at total score 1, 5.1% at total score 2, 10.2% at total score 3, 9.0% at total score 4, 33.4% at total score 5, and 100% at total score 6. Moreover, the rate of AsICH was also correlated with increasing total score: 0% at total score 0, 3.3% at total score 1, 16.7% at total score 2, 23.2% at total score 3, 45.5% at total score 4, and 66.6% at total score 5.

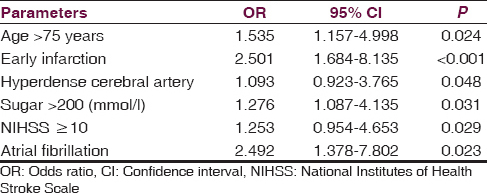

To analyze the variable factors between sICH and without sICH group, the multivariate analysis was performed. Age over 75 years, early infarction, hyperdense cerebral artery, baseline blood sugar more than 12 mmol/l, NIHSS as 10 or more, and AF were the risk factors to develop sICH after treated with rt-PA at 1.535, 2.501, 1.093, 1.276, 1.253, and 2.492 times, respectively [Table 3]. All parameters of SEDAN score and AF showed significant prediction of sICH.

Discussion

The SEDAN score is a predictive score for the risk of sICH among patients receiving i.v. rt-PA.[13] The five variables as well as age, baseline blood glucose, NIHSS, early infarct, and hyperdense artery by CT can be obtained in every primary stroke center.[1013171819202122] Practical to use is the advantage of this score.[1017181920] The SEDAN score had the highest predictive power with moderate performance as compared with the others such as MSS (Multicenter Stroke Survey); HAT (Hemorrhage After Thrombolysis), GRASPS (glucose at presentation, race [Asian], age, sex [male], systolic blood pressure at presentation, and severity of stroke at presentation [NIH Stroke Scale]); SITS (Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke); and SPAN (stroke prognostication using age and NIH Stroke Scale).20 There has been a first external validation study of the SEDAN score reported in the retrospective data from the International Stroke Thrombolysis Register.[22] Our previous study showed the validation of the SEDAN score in real world practice, particularly in Asian population.[10] Moreover, this score was also validated in African and European population.[171823]

For safety reason, the rate of sICH after i.v. rt-PA, as recommended by standard guidelines, should not exceed 7% in certified primary stroke center.[24] The rate of sICH in our study is 4.4%. This rate is a bit higher than our previous report in 2011, however, it is still comparable with which of the other previous studies in Thai population.[78910]

AF is the most common etiology of cardioembolic mechanism in patients with acute ischemic stroke.[25] In general, acute ischemic stroke patients with AF have poorer outcomes as compared to patients without AF.[2627] Cardioembolic infarct caused by AF usually becomes large volume leading to severe deficit and risk of hemorrhagic transformation.[28] Moreover, acute ischemic stroke patients with AF who received i.v. rt-PA also have poorer outcomes as compared to patients without AF.[2930] One important reason for this worse outcome should be the higher rate of sICH after i.v. rt-PA treatment in patients with AF.[31] Our study confirms this finding in Thai population. The odds ratio for the risk of sICH in patients with AF is as high as 2.4. It is surprising that AF is not included in the major tools for sICH predictor available in the literature.[1112131415]

Intravenous rt-PA is a standard treatment for patients with acute ischemic stroke.[2432] However, the fear of sICH restricts the use of rtPA in the real world clinical practice. Clinicians should be happy if there are tools to predict the probability of sICH after rtPA treatment. Many predictive tools have been developed for this purpose.[1112131415] Due to deriving from diverse population, the predictive parameters among the scores are dissimilar.[1112131415] Finding AF as a predictor for sICH in Thai population confirms this phenomenon. Moreover, when those scores are applied to an individual patient, the predictive values are somehow quite varied.[16] Most of the tool scores have been validated in diverse population, however, the accuracy of the scores is lower than which of the original reports.[10131718222333]

Conclusions

Rather than the SEDAN score, AF should be a predictor of sICH in patients with acute ischemic stroke after i.v. rt-PA treatment. We may propose the SEDAAN (Sugar, Early infarct sign, hyperDense middle cerebral artery, Atrial fibrillation, Age, Neurologic deficit) score as the predictor of sICH after i.v. rt-PA in Thai population.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is supported by The National Research University Project of Thailand from Office of Higher Education Commission and Center of Excellence in Integrated Sciences for Holistic Stroke Research from Thammasat University.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thrombolytic Therapies. Philadelphia: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2004. p. :267-81.

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:1245-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke in the United Kingdom: Experience from the safe implementation of thrombolysis in stroke (SITS) register. QJM. 2008;101:863-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved prediction of poor outcome after thrombolysis using conservative definitions of symptomatic hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:240-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke in Asia: The first prospective evaluation. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:549-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke with an integrated acute stroke referral network: Initial experience of a community-based hospital in a developing country. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:42-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age predicts functional outcome in acute stroke patients with rt-PA treatment. ISRN Neurol 2013 2013:710681.

- [Google Scholar]

- External validation of the SEDAN score: The real world practice of a single center. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18:181-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The HAT score: A simple grading scale for predicting hemorrhage after thrombolysis. Neurology. 2008;71:1417-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- A risk score to predict intracranial hemorrhage after recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;17:331-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after stroke thrombolysis: The SEDAN score. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:634-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting the risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage in ischemic stroke treated with intravenous alteplase: Safe Implementation of Treatments in Stroke (SITS) symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage risk score. Stroke. 2012;43:1524-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk score for intracranial hemorrhage in patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2012;43:2293-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting outcomes after transient ischemic attack and stroke. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20:412-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolysis with rt-PA: The SEDAN score. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2015;21:296-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and mortality after treatment with recombinant tissue-plasminogen activator using SEDAN score. Acta Neurol Scand. 2016;133:239-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical study on HAT and SEDAN score scales and related risk factors for predicting hemorrhagic transformation following thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Chin J Contemp Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;15:126-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after stroke thrombolysis: Comparison of prediction scores. Stroke. 2014;45:752-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation assessment of risk tools to predict outcome after thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;125:189-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- External validation of the SEDAN score for prediction of intracerebral hemorrhage in stroke thrombolysis. Stroke. 2013;44:1595-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thrombolysis risk prediction: Applying the SITS-SICH and SEDAN scores in South African patients. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2014;25:224-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870-947.

- [Google Scholar]

- Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atrial fibrillation and stroke: Prevalence in different types of stroke and influence on early and long term prognosis (Oxfordshire community stroke project) BMJ. 1992;305:1460-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute stroke with atrial fibrillation. The Copenhagen stroke study. Stroke. 1996;27:1765-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathophysiological determinants of worse stroke outcome in atrial fibrillation. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30:389-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- IV t-PA therapy in acute stroke patients with atrial fibrillation. J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:6-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is atrial fibrillation associated with poor outcome after thrombolysis? J Neurol. 2010;257:999-1003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between chronic atrial fibrillation and worse outcomes in stroke patients after intravenous thrombolysis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1454-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee; ESO Writing Committee. Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke: Haemorrhage risk after thrombolysis – The SEDAN score. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:246-7.

- [Google Scholar]