Translate this page into:

Intractable Trigeminal Neuralgia Secondary to Osteoma of the Clivus: A Case Report and Literature Review

Ebtesam Abdulla, B.Med.Sc., MD Neurosurgery Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, Salmaniya Medical Complex Manama Bahrain Dr.Ebtesam@hotmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Skull base osteomas (SBOs) are benign tumors that are frequently detected on radiographic images by coincidence. They are known for being slow-growing tumors and rarely symptomatic. The therapeutic approach for SBOs can differ substantially. Depending on the symptoms, size, and location of the tumor, this can range from serial observation to vigorous surgical extirpation. Clival osteoma is extremely rare. We report a case of clival osteoma, causing intractable trigeminal neuralgia due to the pressure effect on the trigeminal nerve at Meckel's cave. We also provide a review of pertinent literature. A 37-year-old woman presented with intractable trigeminal neuralgia. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a large, lobulated, extra-axial lesion involving the right cerebellopontine angle and epicentering the clivus. Pathologically, the specimen was proven to be osteoma. The patient reported complete symptom resolution over a 4-year follow-up period. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first clinical case of intractable trigeminal neuralgia due to clival osteoma.

Keywords

clivus

osteoma

skull base

Introduction

Osteomas are made up of dense, mature bone, and exhibit benign features.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 They mostly arise from the calvarium and the mandible.1 2 3 4 Skull base osteomas (SBOs) are relatively rare; however, they are considered the most commonly benign, paranasal sinus tumors with a point incidence of 0.4 to 1% of the general population.1 2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Osteomas are more common in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.5 to 3:1.1 2 4 6 7 8 9 10 13 SBO is most commonly found involving the anterior skull base in or around the sinonasal cavities.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 However, osteoma may arise from the middle and posterior skull base.11 14 16 18 20 Clival osteoma is extremely rare and has not been reported yet. Here, we report a clinical case of intractable trigeminal neuralgia due to clival osteoma, with a relevant literature review.

Case Description

A 37-year-old woman endorsed a 3-year history of severe, lancinating, paroxysmal pain involving the right lower half of the face extending to the right lower half of the teeth, gums, and lip. The pain was provoked by speech and mastication. She initially had relief with oxcarbazepine and pregabalin but later became refractory to drugs. Her neurological evaluation was normal, aside from hyperesthesia in the right V3 division. A dental check-up was normal.

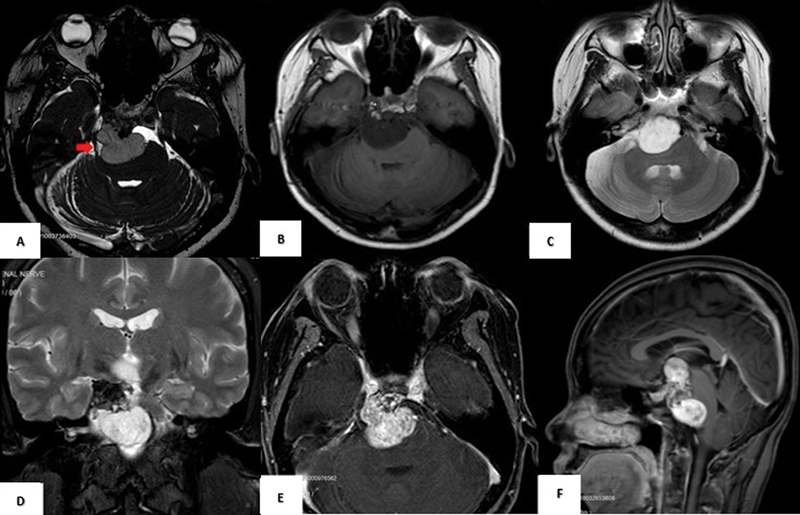

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a large, lobulated, and extra-axial lesion in the area of the right cerebellopontine angle region which epicenter the clivus and caused compression of the right trigeminal nerve fibers at the level of Meckel's cave (Fig. 1A). The mass displayed hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted images (Fig. 1B), predominantly hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1C), and vivid enhancement in the postcontrast T1-weighted images (Fig. 1E and F). The mass was not displaying suppression in the T2-weighted fat saturation images (Fig. 1D). No other abnormalities were seen on MRI. The differential diagnosis entertained was exophytic lesion arising from the clivus, schwannoma, and less likely meningioma.

-

Fig. 1 Preoperative brain MRI shows a mildly compressing mass on the right trigeminal nerve at its cisternal part and the level of Meckel's cave (red arrow) Constructive Interference Steady State sequence (A). The mass is hypointense on T1-W (B), hyperintense on T2-W (C), not suppressed on Short Tau Inversion Recovery sequence (D), and vividly enhanced after contrast (E and F). The mass extends from the third ventricle's anterior aspect superiorly to the pontomedullary junction inferiorly and compresses the midbrain and pons along the right anterolateral aspect (F). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; W, weighted.

Fig. 1 Preoperative brain MRI shows a mildly compressing mass on the right trigeminal nerve at its cisternal part and the level of Meckel's cave (red arrow) Constructive Interference Steady State sequence (A). The mass is hypointense on T1-W (B), hyperintense on T2-W (C), not suppressed on Short Tau Inversion Recovery sequence (D), and vividly enhanced after contrast (E and F). The mass extends from the third ventricle's anterior aspect superiorly to the pontomedullary junction inferiorly and compresses the midbrain and pons along the right anterolateral aspect (F). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; W, weighted.

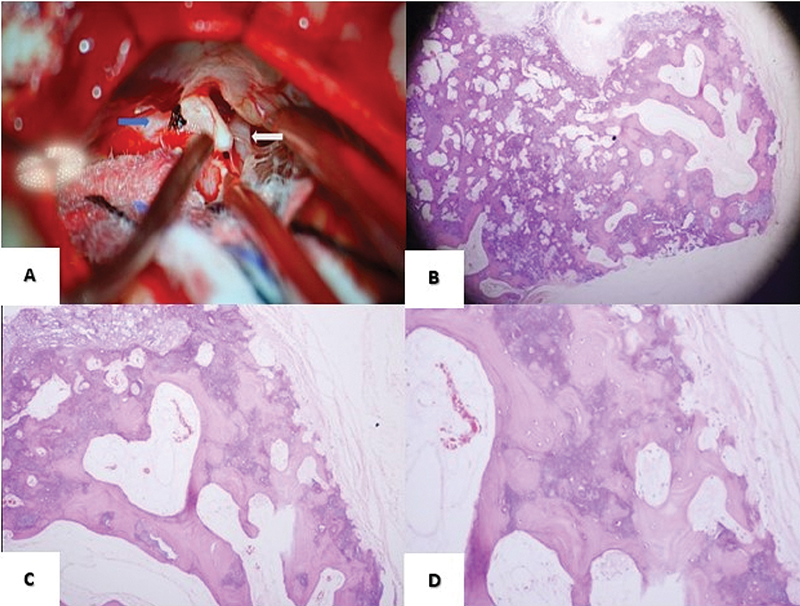

The patient underwent right retrosigmoid craniectomy and decompression of retroclival mass. The mass was hard and calcified with soft elements in between arising from the clivus. The trigeminal nerve was seen displaced and compressed by the mass (Fig. 2A). We mainly aimed to decompress the trigeminal nerve and relieve the facial pain. It was difficult to tackle the whole tumor due to its diffuse nature and vascularity. Thus, total extirpation was not attempted. A diagnosis of Clival osteoma was obtained by histopathology (Fig. 2B-D). The resected mass revealed trabeculae of mature lamellated bone enclosing marrow spaces. No hemopoietic or malignant cells or cartilaginous tissue were detected. The patient recovered well postoperatively. She was discharged on oxcarbazepine and reported a complete symptom resolution over a 4-year follow-up period.

-

Fig. 2 An intraoperative photograph showing osteoma that arises from the clivus (blue arrow) and compresses the trigeminal nerve (white arrow) (A). Histopathology of the clival mass shows osteoma with a capsule, H&E stain, ×40 magnification (B). The low power view shows the osteoma composed of trabeculae of mature bone enclosing empty marrow spaces with capsular tissue in the periphery, H&E stain, ×100 magnification (C). The intermediate power view shows the trabeculae of mature bone with the lacunae containing the osteoblast, H&E stain, ×200 magnification (D). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Fig. 2 An intraoperative photograph showing osteoma that arises from the clivus (blue arrow) and compresses the trigeminal nerve (white arrow) (A). Histopathology of the clival mass shows osteoma with a capsule, H&E stain, ×40 magnification (B). The low power view shows the osteoma composed of trabeculae of mature bone enclosing empty marrow spaces with capsular tissue in the periphery, H&E stain, ×100 magnification (C). The intermediate power view shows the trabeculae of mature bone with the lacunae containing the osteoblast, H&E stain, ×200 magnification (D). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Discussion

SBOs are rare, nonmalignant tumors of uncertain origin. There are three etiologies postulated for osteomas. One is genetic while the others are traumatic causing muscle traction, and inflammatory2 3 20; however, the exact etiology for osteomas' occurrence is unclear.

We conducted a literature search of PubMed and Google Scholar databases on June 20, 2021. We found 50 reported cases of SBOs (Table 1). Adding our case, SBOs were predominately seen in adults with a male predilection. The vast majority of SBOs were unilateral (98%), and only one case was bilateral (1.9%).2 Presenting symptoms (Table 2) mainly were mass effect-type symptoms depending on their location and including headache (62.7%), nasal obstruction (31.3%), ocular symptoms (15.6%), facial pain (7.85%), and apparent mass (5.88%). On the other hand, other rare presenting symptoms have also been reported, such as hemiparesis (1.96%) and convulsions (1.96%), seemingly due to intracranial tumor extension. Our patient had a history of intractable trigeminal neuralgia which manifested as facial pain. We have seen that osteoma originates from the clivus and extends into the cerebellopontine angle. Therefore, we presumed that the patient's facial pain was primarily due to the osteoma's mass effect, pushing and compressing the trigeminal nerve fiber at the Meckel's cave.

|

Study (year) |

Cases |

Presenting symptoms |

Location |

Extension |

Procedure |

Recurrence |

Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bhandari and Jones (1972)14 |

1 |

Convulsion |

PSTB |

No |

Open |

No |

Nominal dysphasia, Wound sepsis |

|

Brodish et al (1999)6 |

7 |

Headache |

ES (n: 7) |

No |

ESS (n: 7) |

No |

CSF leak (n: 2) |

|

Mansour et al (1999)2 |

1 |

ES |

No |

ESS |

NR |

None |

|

|

Akmansu et al (2002)5 |

1 |

Headache, Nasal obstruction |

ES |

No |

ESS |

No |

None |

|

Naraghi and Kashfi (2003)10 |

1 |

Ocular symptomsa |

ES |

O |

ESS |

No |

None |

|

Saetti et a (2005)17 |

1 |

Headache, Facial pain |

ES |

FS, O |

ESS |

No |

Transient retrobulbar pain |

|

Zouloumis et al (2005)4 |

1 |

Headache, Ocular symptomsa |

ES |

FS, O |

Open |

No |

None |

|

Castelnuovo et al (2008)8 |

24 |

Headache, Nasal obstruction, Facial pain, ocular symptomsa |

ES (n: 9), FES (n: 13), SS (n: 2) |

O (n: 3) |

ESS (n: 16), Open (n: 8) |

No |

Transient diplopia, worsening visual acuity, persistent facial pain, facial nerve impairment |

|

Kamide et al (2009)15 |

1 |

Headache, Hemiparesis |

ES |

IC |

Open |

No |

None |

|

Pereira et al (2009)11 |

2 |

Swelling |

Mastoid (n: 2) |

No |

Open (n: 2) |

No |

None |

|

Cheng et al (2013)1 |

1 |

Ocular symptomsa |

ES |

O, FS |

ESS |

No |

Transient diplopia |

|

Sanchez Burgos et al (2013)7 |

1 |

Ocular symptomsa |

ES |

FS, SS, O |

Open |

No |

Frontal osseous irregularity |

|

Alotaibi et al (2013)12 |

1 |

Headache, Ocular symptomsa |

ES |

O |

ESS |

No |

None |

|

Kandakure et al (2019)16 |

1 |

Swelling |

Mastoid |

No |

Open |

No |

None |

|

Humeniuk-Arasiewicz et al (2018)9 |

1 |

Ocular symptomsa, Headache, Nasal obstruction, Facial pain |

ES |

O, FS |

ESS |

No |

None |

|

Alturaiki et al (2018)13 |

5 |

Headache, Nasal obstruction |

ES (n: 1), SS (n: 2), FES (n: 2) |

No |

ESS (n: 5) |

No |

None |

|

Our case (2021) |

1 |

Facial pain |

Clivus |

No |

Open |

No |

None |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ES, ethmoid sinus; ESS, endoscopic sinus surgery; FES, frontoethmoid sinus; FS, frontal sinus; IC, intracranial; NR, not reported; O, orbit; PSTB, petrosquamous temporal bone; SS, sphenoid sinus.

|

Skull base osteomas |

n |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Total number |

51 |

100 |

|

Initial symptoms |

||

|

Headache |

32 |

62.7 |

|

Nasal obstruction |

16 |

31.3 |

|

Ocular symptoms |

8 |

15.6 |

|

Facial pain |

4 |

7.84 |

|

Swelling |

3 |

5.88 |

|

Hemiparesis |

1 |

1.96 |

|

Convulsion |

1 |

1.96 |

|

Origin |

||

|

Ethmoid sinus |

27 |

52.9 |

|

Frontoethmoidal sinus |

15 |

29.4 |

|

Sphenoid sinus |

4 |

7.84 |

|

Mastoid |

3 |

5.88 |

|

PSTB |

1 |

1.96 |

|

Clivus |

1 |

1.96 |

|

Treatment |

||

|

Open surgery |

16 |

31.3 |

|

Endoscopic sinus surgery |

35 |

68.6 |

Abbreviation: PSTB, petrosquamous temporal bone.

A cranial computed tomography (CT) scan was required for radiological diagnosis (Table 2). A CT scan demonstrated features consistent with low-grade bony tumors. They identified a juxtacortical, well-circumscribed sclerotic lesion with the preservation of diploe that did not infiltrate the surrounding soft tissues. On MRI, osteomas are hypointense on T1-weighted images with variable signal intensities on T2-weighted images based on the amount of cancellous bone and compact bone.19 The bulk of the tumors were confined to the ethmoid sinus (27 cases), frontoethmoidal sinus (15 cases), sphenoid sinus (4 cases), mastoid (3 cases), petrosquamous temporal bone (1 case), and clivus (1 case). There was tumor extension to the orbit (10 cases) and frontal sinus (5 cases), mainly from the ethmoid-based osteomas. Sphenoid sinus (1 case) and intracranial (1 case) extensions have been reported. The size of the osteomas varied with the maximum reported 5 cm. In our case, we performed a cranial MRI to evaluate for trigeminal neuralgia. However, we could not do a CT scan to confirm the diagnosis for technical reasons, and the option for surgery was decided.

The differential diagnosis of SBOs should consider the following: osteoid osteoma, ossifying hemangioma, ossifying fibroma, calcified meningioma, and malignant lesions.2 7 11 16 19 In the present case, a sufficient sample was sent for pathological analysis which was typical for compact bone. No hematopoietic or malignant cells or cartilaginous tissues were detected.

In the present view, 35 patients of 51 symptomatic cases underwent endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), and only 16 patients underwent open surgery. ESS or open surgery's decision mainly depends on the site and the tumor's size and the surgeon's preference.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In our case, the aim was to decompress the trigeminal nerve. Hence, open surgery was decided on through a retrosigmoid approach. In the literature, most surgeons attempted total osteoma extirpation and reported no tumor recurrence. However, total osteoma extirpation is not always achievable. In our case, a total extirpation of clival osteoma was not achieved due to its total diffuse nature and vascularity. SBO surgery is relatively safe. However, some patients reported postoperative complications such as nominal dysphasia, wound sepsis, cerebrospinal fluid leak, transient retrobulbar pain, symptoms persistence or worsening, facial nerve impairment, and facial osseous irregularity. Although SBOs seldom recur after surgery, Zouloumis et al and Brodish et al described recurrent cases successfully managed by total extirpation.4 6

Conclusion

Osteoma originating from the clivus is extremely rare; however, it should be included as a differential diagnosis of intractable trigeminal neuralgia. The histopathological assessment is the gold-standard test for diagnosis. Furthermore, microsurgical decompression for trigeminal neuralgia has a good neurological outcome.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- Giant osteomas of the ethmoid and frontal sinuses: Clinical characteristics and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(5):1724-1730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethmoid sinus osteoma presenting as epiphora and orbital cellulitis: case report and literature review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43(5):413-426.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral osteoma of the mandible: a study of 10 new cases and analysis of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(5):467-470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteoma of the ethmoidal sinus: a rare case of recurrence. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43(6):520-522.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic removal of paranasal sinus osteoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(2):230-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic resection of fibro-osseous lesions of the paranasal sinuses. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13(2):111-116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant osteoma of the ethmoid sinus with orbital extension: craniofacial approach and orbital reconstruction. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33(6):431-434.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteomas of the maxillofacial district: endoscopic surgery versus open surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(6):1446-1452.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant fronto-ethmoidal osteoma - selection of an optimal surgical procedure. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed). 2018;84(2):232-239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endonasal endoscopic resection of ethmoido-orbital osteoma compressing the optic nerve. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(6):408-412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mastoid osteoma. consideration on two cases and literature review. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;13(3):346-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic removal of large orbito-ethmoidal osteoma in pediatric patient: case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(12):1067-1070.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fibro-osseous lesions of the paranasal sinuses and the skull base. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;4:1324-1330.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraparenchymal pneumocephalus caused by ethmoid sinus osteoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(11):1487-1489.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteoma of mastoid bone; a rare presentation: case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;71(02):1030-1032.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethmoid osteoma with frontal and orbital extension: endoscopic removal and reconstruction. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(10):1122-1125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteoma of the malleus: a case report and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(4):239-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calvarial lesions: a radiological approach to diagnosis. Acta Radiol. 2009;50(5):531-542.

- [Google Scholar]