Translate this page into:

International Neurosurgery Rotation in New Zealand: Analysis of Operative Experience

Address for correspondence: Dr. Dale Ding, Department of Neurosurgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, 350 W Thomas Road, Phoenix, AZ 85013, USA. E-mail: daleding1234@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

The duration of neurosurgical training in the United States is 7 years and includes 30 months of electives, which allows time for trainees to obtain research or additional clinical experience. The University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia, USA) is one of only a handful of neurosurgical training programs in the United States which still integrates an international rotation. Every year, two residents from the University of Virginia are sent to Auckland City Hospital, and one resident is sent to Christchurch Hospital for a minimum of 12 months. During this yearlong rotation, the residents serve as the equivalent of senior neurosurgical registrars in the Surgical Education and Training program of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. The case volumes from the New Zealand rotation have previously been summarized.[1] However, detailed operative logs regarding the type of cases and lesions encountered during this rotation are absent. Therefore, the aim of this report is to critically analyze the operative experience of a 6th year University of Virginia neurosurgery resident who spent 12 months as a senior neurosurgical registrar at Auckland City Hospital.

A prospectively collected list of operating theater cases performed by a senior neurosurgical registrar at Auckland City Hospital from June 8, 2015, to June 3, 2016, was retrospectively evaluated. Lesions were classified by pathology, location, and presentation. Cases were categorized by the type of procedure performed.

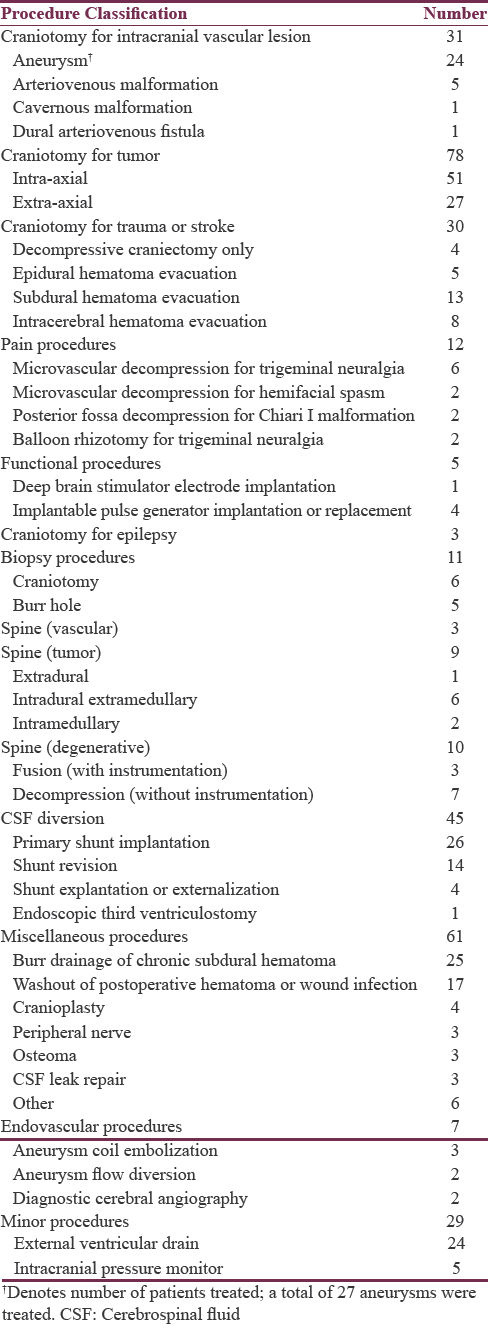

A total of 334 cases were performed by the registrar, and they are summarized in Table 1. The cases included 35 pediatric (age <18 years) patients, ranging in age from 1 month to 16 years. More than 70% of procedures performed by neurosurgeons in the United States are spinal operations, primarily for the treatment of spondylosis. By comparison, <10% of cases in the present analysis were performed for a spinal disorder, which indicates the predominantly cranial bias of the procedures during this rotation. Significant advances in neuroendovascular technology and widespread adoption of endovascular approaches by the cerebrovascular community has substantially decreased the number of intracranial aneurysm patients undergoing surgical treatment in the United States.[2345] The ramifications of this paradigm shift in aneurysm treatment include a more limited exposure of trainees to the microsurgical techniques necessary to perform safe and effective clipping of an aneurysm.

In this analysis, a total of 27 intracranial aneurysms were surgically clipped in 24 patients. Of the 24 aneurysm patients, 18 were treated in the setting of acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (75%). Of the 27 aneurysms, 12 were located on the middle cerebral artery (44%), nine were located at the anterior communicating artery (33%), three were located at the internal carotid artery terminus (11%), and one each were located at the anterior choroidal, distal anterior cerebral, and superior cerebellar arteries (4%). Of the five surgically resected brain arteriovenous malformations, four were ruptured (80%), and one was located in the posterior fossa (20%). The two remaining intracranial vascular lesions included a petrosal dural arteriovenous fistula and a premotor cavernous malformation. An additional 26 nonvascular skull base cases were performed, including 17 tumor resections, eight microvascular decompressions, and one repair of tegmen tympani defect.

In summary, the international neurosurgery rotation in New Zealand exposes residents at the University of Virginia to a wide range of intracranial pathology and affords invaluable operative experience in complex cranial surgery, particularly with regard to vascular and skull base procedures. The rotation sites in New Zealand are not accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, and therefore, these cases are not accounted for in the resident's official procedural log. However, the operative experience obtained during the New Zealand rotation considerably improves the resident's overall competency in both cranial neurosurgery and microsurgery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

I am sincerely grateful to the neurosurgical consultants at Auckland City Hospital, Mr. Edward Mee, Mr. Arnold Bok, Mr. Christopher Furneaux, Mr. Peter Heppner, Mr. Andrew Law, Mr. Robert Aspoas, and Mr. Patrick Schweder for their tutelage and patience during my rotation. I would also like to thank the interventional neuroradiology consultants at Auckland City Hospital, Dr. Stefan Brew, Dr. Ben McGuinness, Dr. Maurice Moriarty, and Dr. Ayton Hope, for their support. Finally, I thank the University of Virginia neurosurgery faculty for the opportunity to rotate at Auckland City Hospital.

REFERENCES

- Neurological surgery training abroad as a progression to the final year of training and transition to independent practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:715-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recession of microsurgical clipping in the modern era of intracranial aneurysm treatment. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2934-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The emergence of endovascular treatment-only centers for treatment of intracranial aneurysms in the united states. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e504-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of unruptured wide-necked intracranial aneurysms: Comparison of dual microcatheter technique and stent-assisted coil embolization. J Neurointerv Surg. 2015;7:256-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Technology developments in endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:135-44.

- [Google Scholar]