Translate this page into:

Intelligence quotient is associated with epilepsy in children with intellectual disability in India

Address for correspondence: Ram Lakhan, Doctoral Candidate in Epidemiology, Department of Epidemiology, School of Health Sciences, College of Public Service, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA. E-mail: ramlakhan15@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Epilepsy is a disorder that is commonly found in people with intellectual disability (ID). The prevalence of epilepsy increases with the severity of ID. The objective of this study was to determine if there is an association between intelligence quotient (IQ) and epilepsy in children with ID.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 262 children, aged 3-18 years, with ID were identified as part of a community-based rehabilitation project. These children were examined for epilepsy and diagnosed by a psychiatrist and physicians based on results of electroencephalogram tests. A Spearman's correlation (ρ) was used to determine if there was an association between IQ scores and the occurrence of epilepsy. X2 statistics used to examine the relationship of epilepsy with gender, socioeconomic status, population type, severity of ID, family history of mental illness, mental retardation, epilepsy, and coexisting disorder.

Results:

Spearman's rho –0.605 demonstrates inverse association of IQ with epilepsy. X2 demonstrates statistically significant association (P < 0.05) with gender, severity of ID, cerebral palsy, behavior problems, and family history of mental illness, mental retardation, and epilepsy.

Conclusions:

Lower IQ score in children with ID has association with occurrence of epilepsy. Epilepsy is also found highly associated with male gender and lower age.

Keywords

Community-based rehabilitation

epilepsy

intellectual disability

India

intelligence quotient

Introduction

Epilepsy is defined as recurrent, unpredictable, and typically unprovoked seizure activity.[1] The prevalence of epilepsy in the general population is estimated to be 40-70/1000 people;[2] people with intellectual disability (ID) have a higher rate of epilepsy diagnoses than the general population. ID was known as mental retardation earlier, and we have used these terms interchangeably in manuscript. Approximately 14-24% of the ID population is affected by epilepsy.[34] The prevalence of epilepsy increases with the severity of ID, which approaches 7% in people with mild to moderate ID, 67% in people with severe ID,[5] and 50-82% in people with profound ID.[67] Dodson[8] reported that children with epilepsy have an intelligence quotient (IQ) score that is 10 points lower than their healthy, age-matched peers.

Epilepsy can affect a person's education, career, general health, mental health, and marriage, among other things.[9] Epilepsy in children with ID affects a number of domains and functions.[1011] For example, epilepsy affects their health-related quality of life outcomes[12] and their ability to function normally.[13] Children with both epilepsy and intellectual disabilities experience psychiatric disorders in 50-59% of cases.[1415] Epilepsy does not only affect the individual but it also negatively affects an individual's family members. In a review article, Bowley and Kerr[16] reported that having ID along with epilepsy affects a person's physical morbidity, which in turn leads to increased mortality and a greater burden on their family.

The risk of death is five times higher in children with epilepsy compared with children without epilepsy.[17] This risk is even higher in children with ID that also have neurological disorders.[17] Because epilepsy is a known neurological disorder,[7] it follows that children who have low IQ scores and epilepsy have an even higher death risk. Given these correlations, a strong relationship seems to exist between epilepsy and low IQ,[18] but very few studies have investigated the nature of this relationship. If the relationship was linear within the ID population, one would potentially be able to predict how a person's IQ score relates to their likelihood of having or developing epilepsy.

Objective

This study investigated the correlation between IQ and epilepsy in children with ID.

Materials and Methods

Demographics and sampling

Ashagram Trust (AGT) is a nongovernment organization. This organization is located in one of the poorest districts of India,[19] in Barwani. A total of 53% of the population in this district lives below the poverty line. The district has both a tribal population (68%) and a nontribal population (32%). The tribal population is more disadvantaged in terms of health, education, and employment compared with the nontribal population.[20] AGT implemented a community-based rehabilitation project in 63 villages of the Barwani block with financial help from Action Aid India. This project began in 1999 and ended in 2010. The project aimed to provide comprehensive services to all people identified to have disabilities. A total of 63 villages were surveyed door-to-door, and a total of 262 children were identified as having intellectual disabilities. All 262 children were included in this study. Consent to test for epilepsy and receive comprehensive rehabilitation services as part of the CBR project was obtained from the children's parents or grandparents.

Diagnosis of intellectual disability and epilepsy

Mental retardation professionals (including the author) assessed children using standard diagnostic tests. Initially, two tests – a developmental screening test (DST)[21] and an Indian adaptation of the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (VSMS)[21] – were used to determine each child's IQ score. The average of development quotient obtained from DST and social quotient from VSMS makes IQ.[22] On place of other standardized test Malins Intelligence Scale for Indian Children, an adaptation of Wechsler Intelligence Scale, DST and VSMS were preferred because these tests can be administered with less time even in nonclinical settings on nonschool going children. Children were also administered other standardized intelligence tests as needed.

All children diagnosed with ID were referred to psychiatrists and physicians to assess and treat, respectively, any medical condition, including epilepsy. While taking case history, professional asked for any symptoms of epilepsy, if there was any symptom than that case was referred for medical evaluation for epilepsy. Then, the child underwent an electroencephalogram (EEG) administered by the psychiatrist or a general physician. EEG was administered for 20-30 min to record brain activities in awaken condition. Abnormal electrical activity (spikes and slowing) considered indication of epilepsy. The EEG results were used to support a positive diagnosis but were not used to rule out epilepsy.[2324] Clinicians heavily relied on the clinical history that was obtained from parents or any other eye witness family member. If available, reports from previous consultations were reviewed and taken into account before making each diagnosis. A few children also underwent a computed tomography scan for diagnosis purposes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Software for Social Science (SPSS version 21) was used for statistical analysis. Spearman's correlation used to examine association of epilepsy with IQs and age of the study participants. X2 statistics is used for gender, severity of ID, socioeconomic status, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, behavior problems, coexisting disorders, and family history of mental illness, mental retardation, and epilepsy.

Results

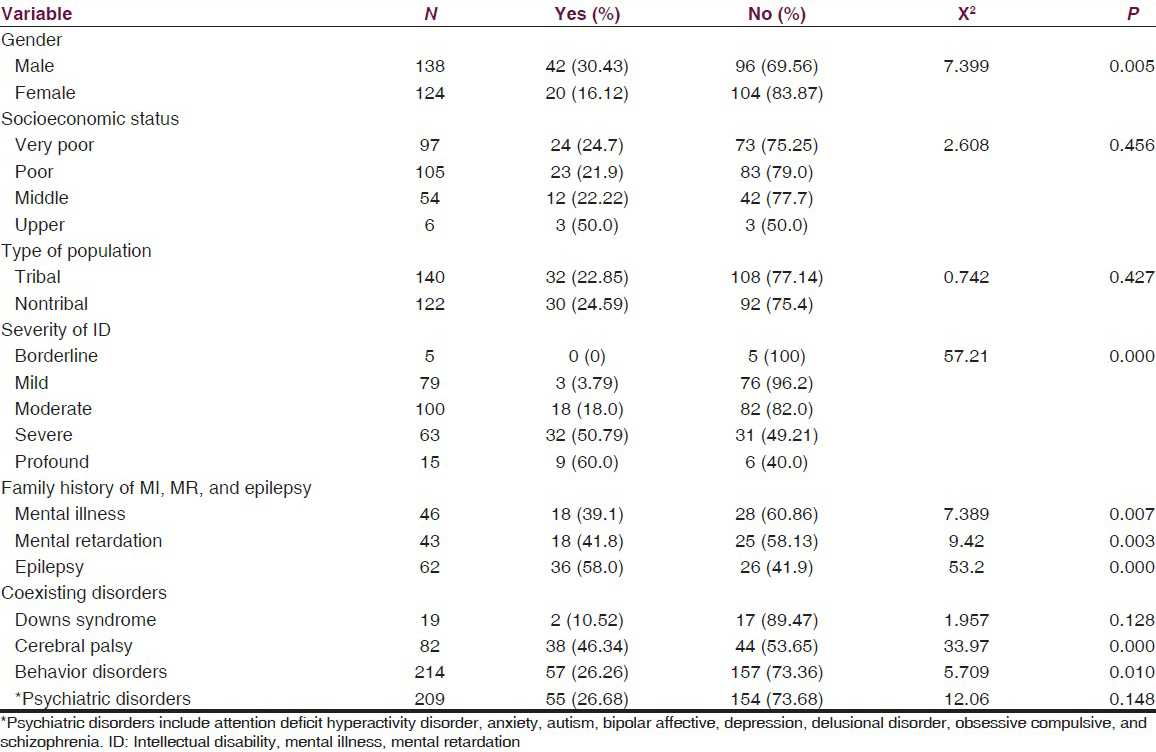

Table 1 categorizes variables characteristics and statistics. We found epilepsy highly associated with male gender than female (X2 −7.399, P = 0.005) and not equally distributed with severity of ID (X2 −57.21, P = 0.001). Epilepsy found strongly associated with the children those have family history of mental illness (X2 −7.389, P = 0.007), mental retardation (X2 −9.42, P = 0.003), and epilepsy (X2 −53.2, P = 0.001). Except psychiatric disorders and Down's syndrome, epilepsy is found more among ID children those had cerebral palsy (X2 −33.97, P = 0.001), and behavior disorders (X2 −5.709, P = 0.01). The occurrence of epilepsy is not different in population groups (X2 −0.742, P = 0.427), and among socioeconomic groups (X2 −2.608, P = 0.456) [Table 1].

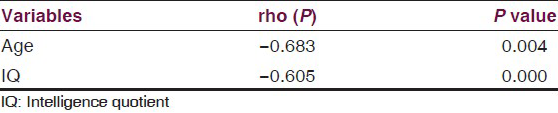

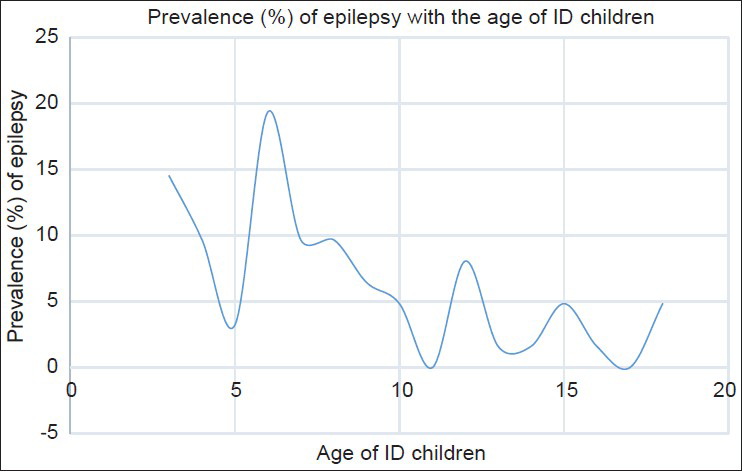

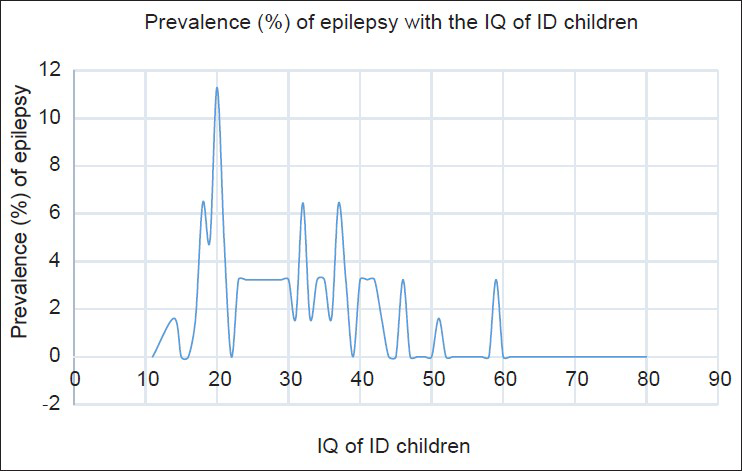

Table 2 it expresses Spearman's rho statistics of epilepsy with the ordinal variables age and intelligence quotient. Epilepsy had inverse correlation with age (P = −0.683), and intelligence quotient (P = −0.605) among children with intellectual disability. Graphs demonstrate that prevalence of epilepsy decreases with the age [Figure 1] and intelligence quotient [Figure 2] of intellectual disability children.

- Graph showing prevalence of epilepsy with the age of intellectual disability children

- Graph showing prevalence of epilepsy with the intelligence quotient of intellectual disability children

Discussion

Spearman's P demonstrates that lower IQ scores are correlated with epilepsy in children with ID. A case-control study conducted in North India demonstrated that children with generalized epilepsy have lower IQ scores than their controls with not epilepsy.[25] A linear decline in IQ is also seen among people who developed epilepsy.[26] Epilepsy also found more associated with male gender and that was consistent with our study. Epilepsy is equally distributed between two populations tribal versus nontribal. Children with ID those had family history of mental illness, mental retardation and epilepsy shown higher chances of having epilepsy.

It is already known that people with ID have higher rates of epilepsy.[57] Further inferring from findings, we can say that people with ID are on higher risk than non-ID and this risk of epilepsy goes further higher among ID as their IQ score lowers.

Studies have shown correlation of epilepsy with poor cognitive function.[2728] Thus, professionals should use extra caution to detect epilepsy as early as person with ID come in their contact so that person can receive early diagnosis and treatment in order to protect from diminishing their cognitive abilities further. ID person those do not have epilepsy also need regular attention by professionals in order to check for any symptom of it, so that immediate care can be offered.

Study limitations

This is a cross-sectional study that demonstrates the relationship between IQ scores, age, and the occurrence of epilepsy in our study group. However, because of its limited design, the study could not be used to determine a causative relationship. In addition, epilepsy has several categories, which were not differentiated in this study. Such information would have been greatly useful.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations, this study adds knowledge to the existing scientific literature by describing that a person's likelihood of suffering from epilepsy increases as IQ scores drop in children with ID. Thus, we can say that children with low IQ have a higher chance of displaying epilepsy and, therefore, should be routinely tested for the condition.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- WHO, Global Campaign against Epilepsy (GCAE): Out of the Shadows. [online] 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/globalepilepsycampaign/en

- [Google Scholar]

- Epilepsy: A manual for medical and clinical officers in Africa, [online] 2002. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67453

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and treatment of epilepsy in patients who are mentally retarded. CNS Drugs. 2000;13:117-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epilepsy in a population of mentally retarded children and adults. Epilepsy Res. 1990;6:234-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epilepsy in school children with intellectual impairments in Sheffield: The size and nature of the problem and the implications in service provision. J Ment Defic Res. 1989;33:511-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental retardation and behavioral disturbances related to epilepsy: A review. Brain Dysfunction. 1989;2:3-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severely retarded children in a defined area of Japan-prevalence rate, associated disabilities and causes. No To Hattatsu. 1991;23:4-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and IQ. In: Pellock JM, Dodson WE, Bourgeois BF, eds. Pediatric epilepsy diagnosis and therapy. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2002. p. :613-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social adjustment and competence 35 years after onset of childhood epilepsy: A prospective controlled study. Epilepsia. 1997;38:708-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The quality of life of children with chronic epilepsy and their families: Preliminary findings with a new assessment measure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37:689-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life in childhood epilepsy: The results of children's participation in identifying the components. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:554-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The health-related quality of life of children with refractory epilepsy: A comparison of those with and without intellectual disability. Epilepsia. 2001;42:621-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A guide to life-style planning: Using the activities catalog to integrate services and natural support system. In: Wilcox B, Bellamy GT, eds. The Activities Catalog: An Alternative Curriculum for Youth and Adults with Severe Disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing; 1987. p. :175-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isle of Wight revisited: Twenty-five years of child psychiatric epidemiology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:633-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with mental retardation and active epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:904-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Death in children with epilepsy: A population-based study. Lancet. 2002;359:1891-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Behavior and mental health problems in children with epilepsy and low IQ. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:683-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Report of the Task Force, Identification of Districts for Wage and Self-Employment Programs, Planning Commission, Bengal Offset Works, New Delhi, India. [online] 2003. Available from: http://planningcommission.gov.in/reports/publications/tsk_idw.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Inclusion of children with intellectual and multiple disabilities: A community based rehabilitation approach, India. J Spec Educ Rehabil. 2013;14:79-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vineland Social Maturity Scale-Indian Adaptation: Enlarged Version. Mysore, India: Swayamsiddha Prakashanam; 1992.

- [Google Scholar]

- The coexistence of psychiatric disorders and intellectual disability in children aged 3-18 years in the Barwani District, India. 2013. ISRN Psychiatry 2013. 875873 Available from http://www.hindawi.com/isrn/psychiatry/2013/875873/abs

- [Google Scholar]

- The epilepsies. In: Wyngoorden J, Smith L, Bennet C, eds. Cecil's Textbook of Medicine (19th ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. p. :2202-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of IQ profile in children with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1992;33:1106-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting cognitive impairment in epilepsy: Findings from the Bozeman epilepsy consortium. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1995;17:909-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of early versus late onset of major motor epilepsy upon cognitive-intellectual performance. Epilepsia. 1975;16:73-81.

- [Google Scholar]