Translate this page into:

Giant primary ossified cavernous hemangioma of the skull in an adult: A rare calvarial tumor

Address for correspondence: Dr. Srikant Balasubramaniam, Department of Neurosurgery, B.Y.L Nair Hospital, Dr. A.L. Nair Road, Mumbai Central, Mumbai -400008, India. E-mail: srikantbala@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangiomas (PICHs) of the cranium are rare benign vascular tumors that account for about 0.2 % of all bone tumors and 10 % of benign skull tumors. They generally present as osteolytic lesions with honeycomb pattern of calcification. Completely ossified cavernous hemangioma of the calvarium in an adult has not been reported previously. A 28-year-old female presented to us with a large right parietal skull mass that had been present since the last 15 years. Total resection of the lesion was performed. Pathological examination was suggestive of cavernous hemangioma of the skull bone. Cavernous hemangioma should be considered as one of the differential diagnosis in any case of bony swelling of the calvarium so that adequate preoperative planning can be made to minimize blood loss and subsequent morbidity.

Keywords

Adult

cavernous hemangioma

ossified calvarial mass

skull lesion

Introduction

Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangiomas (PICHs) of the cranium are rare benign vascular tumors that account for about 0.2% of all bone tumors and 10% of benign skull tumors.[12] These typically present as osteolytic lesions in the calvarium.[2–4] Even though calcification in hemangioma is relatively common, completely ossified cavernous hemangioma of the skull in an adult has hitherto been unreported in literature.[5] Total surgical excision is the treatment of choice and the prognosis after complete excision is excellent and recurrence is usually rare.[26] We present a rare case of a giant cavernous hemangioma of the skull which was completely ossified. The clinical presentation, pathology, differential diagnosis and treatment of this rare disorder are discussed.

Case Report

A 28-year-old female presented to us with history of huge swelling over the right parietal region progressively increasing in size over the past 15 years. There were no significant complaints except for the swelling. On examination, the lesion measured approximately 6 cm in diameter in the right posterior high parietal region. The swelling was firm to hard in consistency, non-tender and immobile. Clinical impression on local examination was that of a hard bony mass arising from the calvarium. Routine hematological examination was normal.

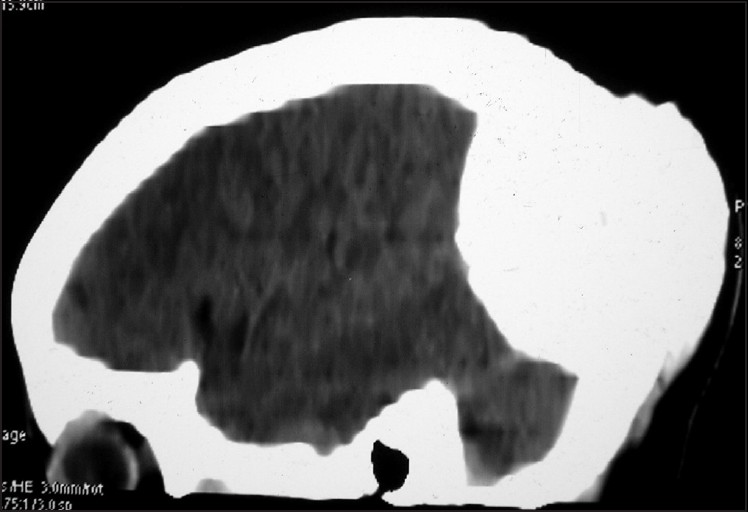

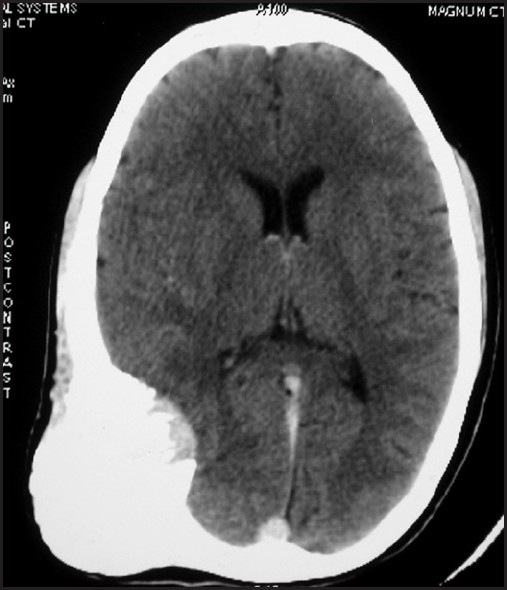

A plain radiograph of the skull was performed which showed a completely radio opaque bony mass in the right parietal region. Plain Computed tomography (CT) of brain with bone window showed a uniform hyperdense mass in the right high parietal region measuring 6.3 × 5.3 × 5.6 cm. The involved bone showed complete erosion of both the inner and outer tables. [Figure 1] Postcontrast CT showed enhancement of extradural soft tissue component with buckling of under lying gray matter. [Figure 2]

- Plain sagittal CT scan showing a completely ossified mass in the high parietal region involving both the inner and outer table of skull

- Postcontrast axial CT scan showing a uniformly hyperdense mass in the right high parietal region with contrast enhancing extradural tissue. There is evidence of buckling of underlying gray matter

Patient was operated in left lateral position. Three burr hole right parieto-occipital craniectomy with total resection of lesion was performed. Intraoperatively lesion was extremely vascular and looked like white coral-filled with vascular soft tissue. Patient was extubated on table with no added neurological deficits. Patient was in regular follow-up and was subjected to cranioplasty 6 months later. At 3-years follow-up there is no recurrence of lesion.

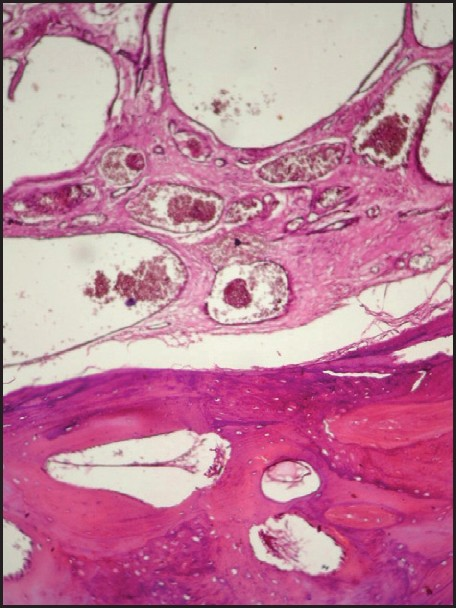

The histopathology showed bone bits with mature lamellar bone and bony spicules. The lamellar bone showed concentrically arranged lamellae (collagen) around vascular canal (Haversian canal). Medullary spaces between bony trabeculae showed ectatic thin-walled blood vessels with single layer of flat endothelial cells. [Figure 3] The lesion was consistent with the diagnosis of cavernous hemangioma with ossification.

- H and E-stained slide showing bone bits with mature lamellar bone and bony spicules. Medullary spaces between bony trabeculae showing ectatic thin-walled blood vessels with single layer of flat endothelial cells

Discussion

PICHs are rare, benign skeletal tumors most commonly found in the spinal vertebral column. Less commonly, PICHs can involve the bones of the cranium. Overall, they represent 0.7% of all osseous neoplasms.[2] The earliest description in the English literature was in 1845 by Toynbee, who reported a vascular tumor arising in the confines of the parietal bone.[7] Although the origin of PICHs remains obscure, some authors believe that they represent congenital lesions that manifest in adulthood. In a review by Wyke, 70% of cranial PICHs were localized to the calvarium, particularly the parietal and frontal bones.[1]

They are predominantly seen in patients in their fourth and fifth decades.[2–8] However, there are a couple of reports of cavernous hemangiomas in neonates or infants which have been misdiagnosed as ossified cephalhematoma.[910] Unlike the age predominance, our patient was a young adult (28-year old). The female-to-male ratio ranges from 2:1 to 3:1.[8] Hemangiomas are classified histologically by the predominant type of vascular channel in the lesion: Capillary, cavernous, venous and arteriovenous. In the cavernous variety, the capillaries are widely dilated seperated by fibrous tissue.[5] This variety is the commonest in the calvarium with a preference for the frontal and parietal bone.[26]

Calcification within the hemangioma is common and may be of three types. The first variant, nonspecific type is either amorphous or, at times, curvilinear. The second type, which is more specific and is the most frequent type of calcification, is the phlebolith. Occasionally, metaplastic ossification may be found in hemangiomas, and this is the third type of calcification.[5] When bone is involved resulting in reactive osteoclastic and osteoblastic remodeling, the characteristic trabeculated, honeycomb appearance is visible on CT.[26] In our case, however, the whole lesion was ossified.

Calvarial hemangiomas are slow-growing tumors that are only symptomatic when they become large or compress adjacent neurological structures.[11] They develop in the diploic space constituted by dilated blood vessels with fibrous septa and their vascular supply is frequently from the middle meningeal artery and branches of the external carotid artery.[68] They are usually solitary but multiple hemangiomas of the skull have been reported with a frequency of 15% of all identified calvarial hemangiomas.[12]

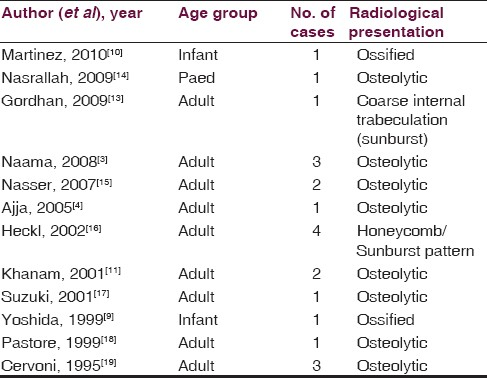

CT is the investigation of choice and calvarial hemangiomas typically appear as a lytic expansile and “bubbly” lesion with a sclerotic rim or a spiculated “sunburst” skull tumor. CT is also helpful in delineating the osseous extension to adjacent skull structures and possible complications such as inner or outer table bone fracture.[8] Nonenhanced CT usually shows a mass isodense with adjacent muscles with intense enhancement after intravenous contrast administration.[5] In this case the lesion was completely hyperdense on plain scan. Other radiological investigations include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and scintigraphy, which was not done in our case.[2813] A table mentioning various reports and series of solitary intraosseous cavernous hemangiomas of the skull vault in literature show the rarity of ossification in these lesions [Table 1].[349–111314–19]

The differential diagnosis of a solitary circumscribed expansile intradiploic cranial lesion includes an osteoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, giant cell tumor, fibrous dysplasia, Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis, sarcoma, meningioma, metastatic disease, Pagets disease and dermoid tumor.[613] Rare intraosseous meningiomas, also known as primary extradural meningiomas, represent only 1–2% of all lesions of this group and may be difficult to distinguish from calvarial hemangiomas solely on the basis of location.[8]

The best treatment for hemangiomas is total surgical resection of the lesion.[26] Embolization before surgery is helpful in preventing excessive bleeding in large tumors.[69] Radiation has been attempted to treat hemangiomas, and it has been shown to stop tumor growth; however, it has not been shown to reduce the size of the tumor.[20] Nasrallah et al have done embolization followed by craniotomy, preserving the outer table with no recurrence at 3-year follow-up.[14]

Cavernous hemangioma of the calvarium is a benign condition of the skull bone which can be completely resected with good results. These lesions usually have typical radiological imaging features, which may, however, show some variations. Cavernous hemangiomas should be considered as a differential diagnosis even in completely ossified calvarial masses and adequate preparation to minimize blood loss such as embolization can be considered if they are adequately investigated considering this possibility.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Primary hemangioma of skull: A rare cranial tumour. Am J Roentgenol. 1946;61:302-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary Intraosseous Skull Base Cavernous Hemangioma: Case Report. Skull Base. 2003;13:219-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cavernous hemangioma of the parietal bone: A case report. J Neurosurg Sci. 2005;49:159-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Case of Calvarial Hemangioma in Cranioplasty Site. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46:484-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- An account of two vascular tumours developed in the substance of bone. Lancet. 1845;2:676.

- [Google Scholar]

- AJR Teaching File: Nuclear Imaging of a Tender Skull Mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(6 Suppl):S61-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cavernous hemangiomas of the cranial vault in infants: A case-based update. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:861-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calvarial hemangiomas: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:63-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Symptomatic Calvarial Cavernous Hemangioma: Presurgical Confirmation by Scintigraphy. Radiology Case. 2009;3:25-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cavernous hemangioma of the skull: Surgical treatment without craniectomy. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;4:575-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraosseous cavernous hemangioma of the frontal bone. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2007;47:506-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cavernomas of the skull: Review of the literature 1975-2000. Neurosurg Rev. 2002;25:56-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroradiological features of intraosseous cavernous hemangioma: Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001;41:279-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cavernous hemangioma of the parietal bone: Case report and review of the literature. Neurochirurgie. 1999;45:312-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of radiation therapy on extracerebral cavernous hemangioma in the middle fossa: Report of three cases. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:912-2.

- [Google Scholar]