Translate this page into:

Feasibility and acceptability study of risk reduction approach for stroke prevention in primary care in Western India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Vikas Dhikav, Department of Health Research, MoHFW, Government of India, ICMR-National Institute of Implementation Research on Non-Communicable Diseases, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. dhikav.v@icmr.gov.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Dhikav V, Bhati N, Kumar P. Feasibility and acceptability study of risk reduction approach for stroke prevention in primary care in Western India. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2023;14:698-702.

Abstract

Objectives:

Stroke is among the leading cause of morbidity and mortality and prevention is the need of the hour. Risk assessment of stroke could be done at primary care. A study was hence planned to assess if an information, education, and communication (IEC) intervention module could be used to address risk factors of stroke among attendees of primary care in Western India.

Materials and Methods:

Patients (>30 years) attending primary care center were enrolled (n = 215). Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) questionnaire was administered at baseline and end line, and detailed diagnosis (hypertension and/diabetes, stroke, coronary artery disease, etc.) was noted from written records. A predesigned IEC module was administered about stroke, risk factors, and their prevention. Body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio were taken before and after 16 weeks.

Results:

A total of 215 participants (M: F = 85:130; mean age = 51.66 ± 13.32 years) had risk factors such as hypertension (26.7%), diabetes (32.5%), history of stroke (n = 3; = 1.39%), and 7.4% (16/215) had coronary artery disease. Before and after comparison of KAP scores indicated significant difference (62.23 ± 19.73 vs. 75.32 ± 13.03); P ≤ 0.0001). Change of waist-to-hip ratio occurred from baseline 0.91–0.9 (P ≤ 0.001). Comparison of the proportion of patients taking antihypertensives before and after IEC intervention was statistically significant (P < 0.05), indicating improvement in drug compliance. BMI comparison changed marginally (26.5 ± 4.7 vs. 26.2 ± 4.5) before and after but was not significant (P ≥ 0.05). The intervention was found to be feasible and acceptable.

Conclusion:

IEC intervention appears to be a low-cost, feasible, and acceptable implementation model for addressing risk factors for stroke in primary care.

Keywords

Stroke

Primary prevention

Information

Education and communication

INTRODUCTION

Stroke is among the leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years (DALY).[1] In fact, the past two decades have shown an increase in the risk factors for stroke amenable to primary prevention, for example, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking, and alcohol drinking.

At present, third-fourth of all stroke-related morbidity and mortalities occur in developing countries. This is assumed to be due to aging, changing pattern of lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors. In short, stroke is emerging as a major public health issue in developing nations.[2] Controlling blood pressure alone can have a significant risk reduction of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke.[3]

The rising burden of stroke,[3] especially in low-income and middle-income countries, is a cause for concern.[1,2] Cost-effective interventions at the primary care level that have the potential to reduce cardiovascular risk in the population, for example, information, education, and communication (IEC) can have a substantial impact on stroke burden. Hence, a need was felt to have a novel, low-cost, comprehensive, workable, and feasible model for stroke prevention in primary care which could be implemented. A study was planned to assess if IEC intervention could be used to address risk factors for stroke among attendees of primary care in Western India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

This is a cross-sectional study of the patients coming to primary care for general medical (e.g., B.P./Sugar) check-up under the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Stroke Program (n = 325) in Western India (n = 215).

For the purpose of the study, initial interaction was done with 325 patients, of which 215 patients agreed to be part of the study.

Questionnaire

Semi-structured knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) questionnaire was administered to all participants, and baseline and end-line details of patients, namely, demographic information, diagnosis of hypertension and diabetes, stroke, and coronary artery disease were noted from written medical records. A questionnaire (Hindi) was constructed and consisted of 20 questions (Knowledge = 7; Attitude = 5; and Practice = 8) related to basic information related to stroke, its risk factors, and prevention.

Assessment

Body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio was taken before and after the completion of the study which lasted for 16 weeks (October–January 2022).

IEC module

Predesigned IEC intervention module was administered to all participants before and after the study about stroke, risk factors, and its prevention.

Health education about the nature of stroke and its risk factors was imparted to study participants, along with counseling related to lifestyle factors linked to stroke. Lifestyle factors, for example, quitting smoking, reducing alcohol intake, and adopting physical activities (e.g., walking/yoga) were suggested ad libitum. A minimum period of 30–60 min daily was suggested however

Counseling was given to the group of 4–6 subjects, in a single setting, and lasted for about 10 min each session. A reinforcement telephonic call was given to participants at fortnightly intervals

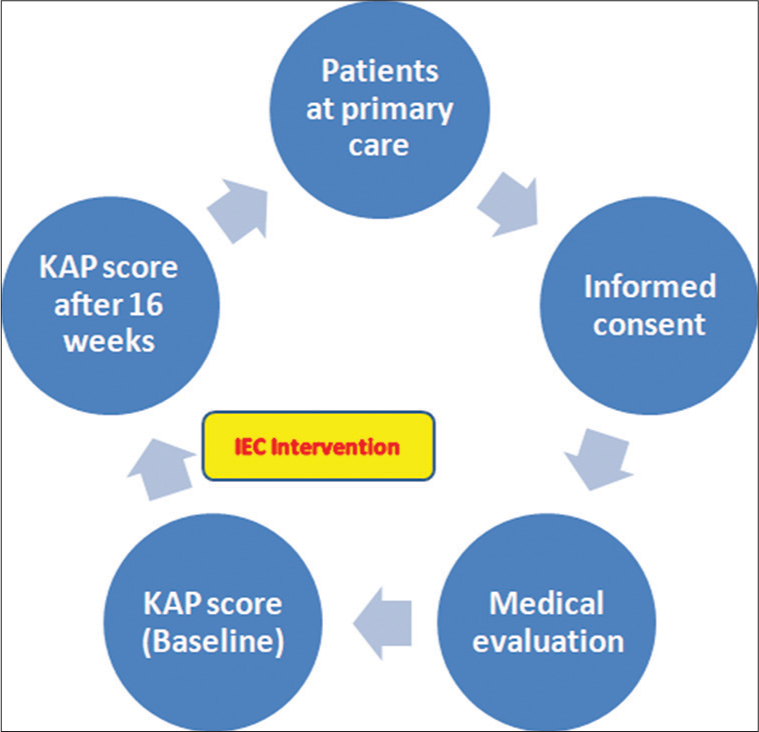

If the patient was already on medications, then psychoeducation about the need for taking regular medications was emphasized. The study flow is given in Figure 1.

- Study flow.

Ethics

A written and informed consent was taken from all study participants and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee ICMR-NIIRNCD, Jodhpur (Rajasthan).

Statistics

Comparison of before and after KAP scores, BMI, was done using paired t-test. The chi-square test of proportion was used to compare the compliance before and after the intervention.

RESULTS

A total of 215 participants (M: F = 85:130; mean age = 51.66 ± 13.32 years) were enrolled for a period 16 weeks. Break up of risk factors in the present study is given in Table 1. Main reasons for visiting the primary health care center were for getting blood pressure and sugar checked (84.15%), fever, cough/cold (6%), and miscellaneous (9%). The majority of the patients were educated till the undergraduate level (65%), 25% were illiterate, and 20% consisted of graduates or above. Hypertension and diabetes were major diseases for which consultation was sought at the primary care level (47% and 33%, respectively).

| Mean age±SD | 51.66±13.32 years | ||

| Hypertension | 26.7% | ||

| Diabetes | 32.5% | ||

| History of stroke | 1.39% | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 7.4% | ||

| KAP scores | Before | After | P-value |

| 62.23±19.73 | 75.32±13.03 | ≤0.0001 Statistically significant | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.91 | 0.9 | ≤0.05 Statistically significant |

| Body mass index | 26.5±4.7 | 26.2±4.5 | ≥0.05 Not statistically significant |

KAP: Knowledge, attitude, and practice, SD: Standard deviation

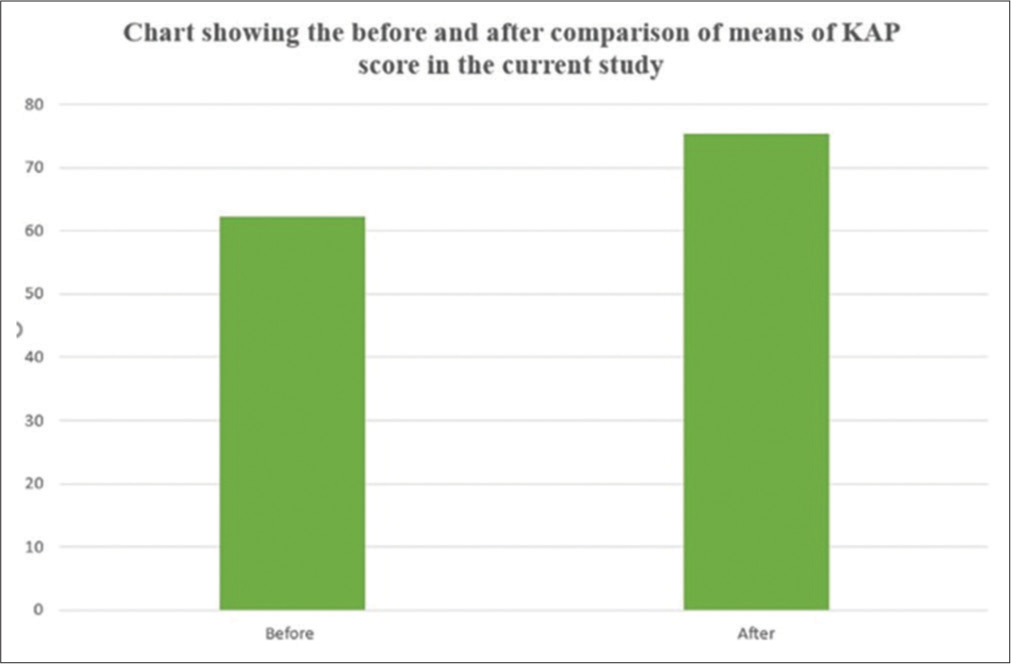

Before and after comparison of means of KAP score in the present study was done and results indicated that there was a statistically significant difference between before and after groups (62.23 ± 19.73 vs. 75.32 ± 13.03); P ≤ 0.0001). Diabetes and hypertension were the main cardiovascular risk factors in the present study group.

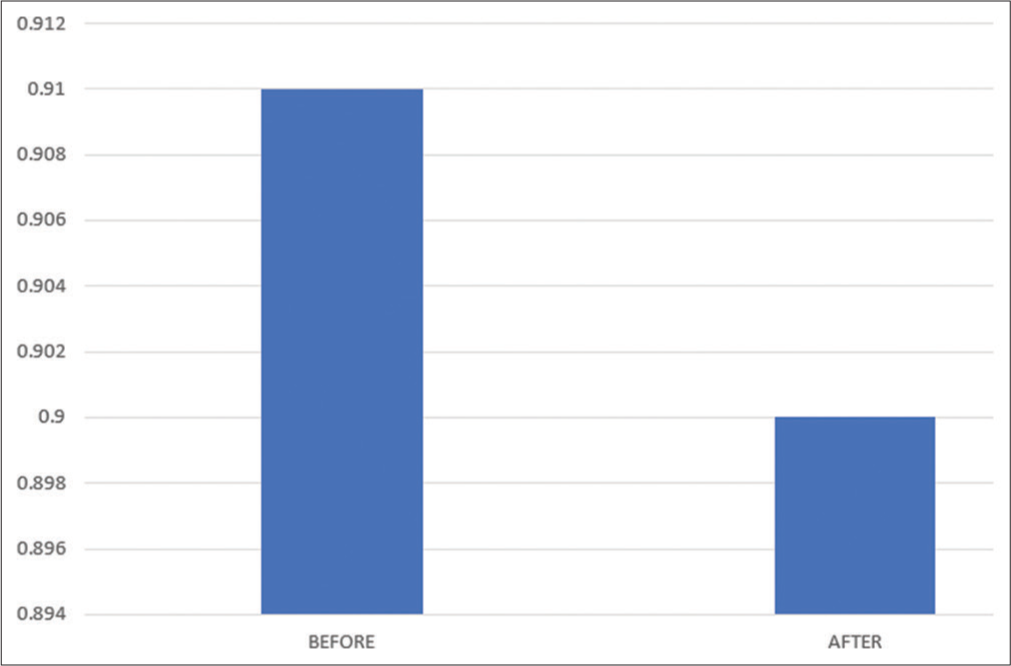

Change in waist-to-hip ratio occurred in the present study from baseline 0.91–0.9 in the present study with statistically significant results (P ≤ 0.001; Figure 2). Comparison of the proportion of patients taking antihypertensives before and after the 16 weeks of IEC intervention [Figure 3] had a significant effect (P ≤ 0.05). BMI comparison changed marginally (26.5 ± 4.7 vs. 26.2 ± 4.5) before and after but was not significant (P ≥ 0.05). Comparison of the proportion of patients taking antihypertensives before and after IEC intervention was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Overall, the intervention was found to be feasible and acceptable by the majority (215/325; 66.15%). Blood sugar (Fasting) showed a decline from 144 ± 73 mg/dL to 124 ± 58 mg/dL (P = 0.01). KAP scores improved significantly in before and after groups [Figure 4].

- Change in waist-to-hip ratio.

- (a and b) Change in compliance to anti-hypertensive (a) and anti-diabetic medications (b) after 16 weeks of intervention.

- Change in knowledge, attitude, and practice score in the present study before and after.

DISCUSSION

The present study reports improvement in KAP scores (before and after comparison) regarding stroke prevention in primary care. Change of waist-to-hip ratio occurred from baseline and comparison of the proportion of patients taking antihypertensives before and after IEC intervention was statistically significant. BMI comparison changed marginally but was not statistically significant.

Rising burden of stroke-related disability

Costs of stroke care are rising providing the impetus to direct our research focus toward effective measures of stroke prevention in primary care[3] but studies focusing on prevention in primary care are virtually non-existent. Effective tobacco control, lifestyle changes, for example, physical activities, salt reduction, and other dietary interventions (reduced high sugar/fat consumption), and controlling blood pressure and diabetes are effective in the primary prevention of stroke, but the implementation of the same in primary care[4] is challenging.

Stroke prevention[5,6]

Developing cost-effective stroke prevention models for primary care is a priority for stroke prevention. Stroke prevention programs involving community health workers in rural areas in health have the potential to be effective in lower- and middle-income countries like India, particularly for tobacco cessation, blood pressure, and diabetes control.[4]

A study from central India from 24 districts showed critical gaps in key items required for the management of non-communicable diseases in primary care. The increasing burden of non-communicable diseases such as hypertension[5] and diabetes mellitus necessitates public health response through health systems.[6]

Over two decades ago, it was suggested that it is important to prohibit tobacco use and adjust dietary habits to control body weight and associated conditions such as diabetes mellitus for primary prevention of stroke.[7] In a similar study addressing the tobacco cessation, it has been envisioned that about half of the cardiovascular diseases are attributable to smoking. In the present study, primary prevention addressing risk factors, for example, smoking cessation was attempted.[8] In fact, it has been suggested that non-communicable disease clinics could be used for tobacco cessation.[9]

A proposed trial in 20 villages in Tibet and 20 villages in Haryana, India will train community health workers to manage and follow-up high-risk patients on a monthly basis.[10] Similar study involving 120 villages in China[11] and Tanzania is underway.[12]

The highest age-standardized stroke-related mortality and DALY rates were in the low-income group.[13] It has been realized that the stroke burden cannot be effectively halted and reversed without effective and widely implemented primordial and primary stroke prevention measures.[14,15] India is likely to suffer a huge social and economic burden in the rehabilitation of stroke patients due to increased life expectancy and urbanization.[16] A stroke mortality reduction approach is being developed.[16]

Stroke preventive strategies[17,18]

Although the use of educational activities[17] in post-stroke period has been tried;[18] to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that shows the use of information, education, and awareness activities in improving risk factors and knowledge regarding preventing them in primary care.

For preventing stroke in general, two major strategies have been proposed, that is, high-risk strategy or population-level strategy.[2] In the high-risk strategy, those at higher risk of developing the disease are identified e.g., hypertension and diabetes.[19,20] Individual may not have a specific disease or health condition, for example, hypertension or diabetes but may have higher risk such as pre-hypertension or smoking.[21] In population-level strategy, lifestyle change is suggested. Simple interventions such as reduced salt consumption, increase fruits and vegetable intake, increased physical activity, weight loss, reduced alcohol intake, and managing psychosocial stress could be important in reducing overall cardiovascular risk.[22,23] A recent cluster randomized trial from Nepal showed the feasibility of lifestyle change implemented through community health workers in reducing blood pressure.[24]

Mean age of individuals enrolled in the present study was 51.66 ± 13.32 years; indicating, the right target group to address stroke prevention in the present study. This is because stroke occurs 15 years earlier in lower- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries.[24]

Policy implications

Current work assumes public health significance due to the rising number of cases of stroke in India, and also in light of the World Stroke Organization international survey which showed that recommended primary prevention activities are being done only in one-third of the 82 countries studied. Furthermore, important is the fact that aspirin, the mainstay for secondary stroke prevention may not be beneficial for primary prevention of stroke.

CONCLUSION

There was a statistically significant difference in the KAP scores regarding risk factors for stroke prevention among those attending Primary Health Center for a general health check-up before and after the study period. There was an increase in the proportion of patients taking anti-hypertensive drugs before and after the intervention. IEC intervention appears to be a low-cost, feasible, and acceptable implementation model for addressing risk factors for stroke in primary care in India.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to acknowledge the help of Anand Upadhyay, and all other healthcare workers at Madhuben Primary Healthcare Center, Jodhpur (Rajasthan). Furthermore, the authors express their gratitude to Dr. Balwant Manda, CMHO Jodhpur for allowing to complete the work in the primary health-care center.

Declaration of patient consent

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) permission was obtained for the study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Preventing stroke: Saving lives around the world. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:182-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): A case-control study. Lancet. 2010;376:112-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroke happens suddenly so it cannot be prevented: A qualitative study to understand knowledge, attitudes, and practices about stroke in rural Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11:53-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognition and cardiovascular comorbidities among older adults in primary care in West India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2023;14:230-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: Evidence and implications. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180640.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of primary care facilities for cardiovascular disease preparedness in Madhya Pradesh, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:408.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strokes in the elderly: Prevalence, risk factors and the strategies for prevention. Indian J Med Res. 1997;106:325-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the impact of culturally specific patient-centric behavioral intervention package versus usual care for tobacco cessation among patients attending noncommunicable disease clinics in North India: A single-blind trial pilot study protocol. Tob Use Insights. 2021;14:1179173X211056622.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Using non-communicable disease clinics for tobacco cessation: A promising perspective. Natl Med J India. 2018;31:172-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a simplified cardiovascular management program in Tibet, China and Haryana, India: Study design and rationale. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:924.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population impact of a high cardiovascular risk management program delivered by village doctors in rural China: Design and rationale of a large, cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:345.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of training community health workers and their interventions on cardiovascular disease risk factors among adults in Morogoro, Tanzania: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:552.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:795-820.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digital health in primordial and primary stroke prevention: A systematic review. Stroke. 2022;53:1008-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The global burden of stroke and need for a continuum of care. Neurology. 2013;80(3 Suppl 2):S5-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of a community-based intervention for cardiovascular risk factor control on stroke mortality in rural Gadchiroli, India: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:764.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of personalized virtual reality in education for patients post stroke-a qualitative case series. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28:450-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The application of virtual reality in patient education. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;59:184-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Two decades of progress in preventing vascular disease. Lancet. 2002;360:2-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: The Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388:2665-712.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet Commission on hypertension: Addressing the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:564-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention led by female community health volunteers versus usual care in blood pressure reduction (COBIN): An open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e66-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]