Translate this page into:

Epidemiological study of the prevalence of depressive disorders in primary health care in Morocco

Address for correspondence: Dr. Bouchra Oneib, Department of Psychiatry, University Psychiatric Center Mohammed VI, 60020 Oujda, Morocco. E-mail: boucha82@hotmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

To determine the prevalence and the impact of depressive disorders in primary health care and its associated factors.

Methodology:

It's a cross-sectional study with 351 participants selected from Moroccan primary care facilities, aged above 18 years without chronic somatic or psychiatric disease. The participants answered a questionnaire that included demographic characteristics, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for major depressive episode (MDE), dysthymic disorder and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Statistical analysis was performed by the SPSS 13.0 software.

Results:

The prevalence of depressive disorders in the sample was 13.7%, that of MDE was 9.1%, while dysthymic disorder was 4.3%, the rate of recurrent depressive episodes was 38.2% (6% of participants), and the prevalence of depression over a lifetime was 17.7%. The percentage of depression was higher among women than men (P = 0.01). 6.3% of depressed patients have already attempted to suicide. Analysis of GAF scores showed an average of 76.2 ± 24, a lower score was significantly found among patients with current MDE (P = 0.001), dysthymic subjects (P = 0.001) and those who suffer from recurrent MDE (P = 0.001). Depressive disorders in univariate analysis were associated with: Female gender P = 0.01 odds ratio (OR) 2.1 (1.09–4.3), unemployment P = 0.02 OR 0.4 (0.2–0.9), and childbearing age P = 0.004 OR 3.5 (1.5–8). Adjusted OR has not demonstrated a significant association.

Conclusion:

The high prevalence of depressive disorders, suicide risk, and the alteration of the quality of life among primary health care patients in Morocco suggest the importance of identifying and treating this population.

Keywords

Associated factors

depressive disorders

Morocco

prevalence

primary health care

Introduction

Depressive disorders are within the most prevalent mental disease worldwide.[12] According to an epidemiological study of affective disorders in the USA, the prevalence of major depressive disorder for a lifetime was 16.2%,[3] while in Morocco, a national survey conducted in 2005 showed a prevalence of 26.5% in the general population.[4]

We know that 40–50% of depressed patients are detected in primary health care, and 20% receive adequate treatment.[5] Early diagnosis can improve well-being of patients, ensure a better antidepressant response and reduce the risk of recurrence and suicide.[67]

The objective of the study is to determine the prevalence and the impact life of depressive disorders in primary health care and its associated factors.

Methodology

Study sample and procedure

This is a cross-sectional study over 2 years from 2012 to 2014, on a sample of Moroccan consultants in primary health care in two cities.

The sample size was calculated using the following formula:

N = 1,962 p. (1- p)/margin of error2

With:

-

p: The expected proportion of subjects presented a depression

-

Margin error: Between 0,032 and 0.052

The patients must be aged 18 years old or more. We excluded subjects who were treated for a psychiatric disorder and/or chronic and disabling physical illness such as diabetes, endocrine disorders, neurological disorders, cancer, and others. We also excluded the subjects who refused to participate in the study, and those who have not given their verbal consent.

Data collection was carried out by psychiatrist and physicians who received psychiatric training for the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). It was conducted using a standardized questionnaire with two parts.

The first part assesses the demographic characteristics of consultants; the socioeconomic level of the participants; and physiological status of women. To determine the socioeconomic level of the participants, we used the scale “The Problems Meeting Basic Needs,” which include five items specifying, in the last 30 days, if the participants met with serious problems regarding basic specified encompassing food, transportation, finance, shelter, and clothing.[8] Among women, we specified the childbearing status.

The second part used the MINI, to assess major depressive episode (MDE) (current and anterior), depressive episode with melancholic features, dysthymic disorder, and suicide risk. The MINI has been translated and validated in Moroccan dialect;[9] the validity study demonstrated a satisfactory quantitative assessment of the value of kappa >0.8. We assessed also the quality of life by “Global Assessment of Functioning” (GAF) which is a numerical scale (from 0 to 100) used to evaluate the psychological, social and professional performances of an individual. The research communities affirmed that the reliability of the scale GAF is good specifically when it is used in patients with a mood disorder.[10]

The time spent to evaluate each participant by the questionnaire was 30 min.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 13.0 software provided by the laboratory of Biostatistics, faculty of medicine Rabat. A descriptive analysis of the different parameters was made. Quantitative variables were described as a means ± standard deviation and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. A search for factors associated with depressive disorders was made using the Chi-squaretest or Student's t-test. Then logistic regression was used to take into account possible confounding factor. A P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

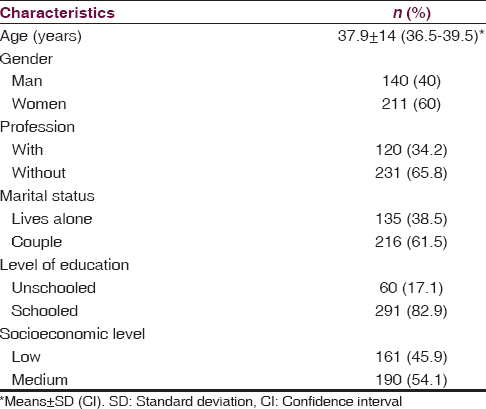

The sample was composed of 351 patients, 211 (60%) of women and 140 (40%) of men. About 181 (85.5%) women were in reproductive age. A significant age difference was observed (P = 0.0001) between men (40 ± 16.7) and women, (36.5 ± 12) [Table 1].

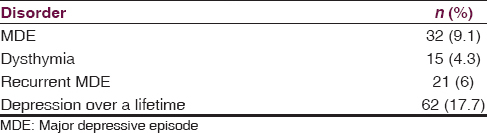

The prevalence of depressive disorders was 13.7%, MDE and dysthymia are more common among women than men (P = 0.0001, P = 0.05, respectively) [Table 2].

The melancholic features were found among 22, 6% of depressive patients and 6.3% of these patients have already attempted to suicide.

The prevalence of MDE in men who have attempted to suicide was 16.7% versus 2.8% among women without a statistically significant difference (P = 0, 2).

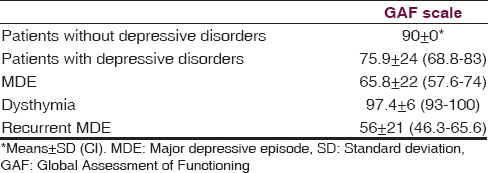

Results of the general GAF score showed an average of 76.25 ± 24, a lower score was found in patients with current MDE (P = 0.0001), dysthymic subjects (P = 0.0001) and those who suffered from recurrent MDE (P = 0.0001) [Table 3].

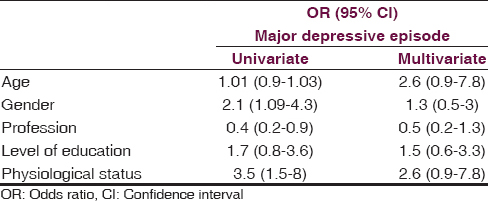

The univariate analysis reveals that the MDE was associated with the following variables: Female gender P = 0.01 odds ratio (OR) 2.1 (1.09–4.3), unemployment P = 0.02 OR 0.4 (0.2–0.9), and child-bearing age P = 0.004 OR 3.5 (1.5–8), whereas this association was not significant according to multivariate analysis [Table 4].

Discussion

Depressive disorders have a negative influence on the quality of life of patients and their professional competence.[1112] This disease also is known by its suicide risk. Indeed, 16% of depressed patients died by suicide.[1314]

In clinical practice, the first contact with these patients will be at the primary care.[15] However, identifying patients with depressive symptoms can be difficult for the primary care physicians due to the diversity of depressive spectrum.[1617]

Our study showed that depressive disorders are common in primary care, and depressed patients have a disrupted social and professional functioning.

According to our results, 13.7% of patients in primary care meet the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV of depressive disorders. This prevalence is lower than that found in other studies where the prevalence was between 22.6% and 30.3%.[181920]

In the present study, 9.1% of patients had an MDE, a prevalence lower than that some previous studies,[121] but much higher than others conducted in the general population.[3222324] Such disparity can be explained by the difference in methodological assessment of depressive disorders.

In addition, 4.3% subjects screened had a dysthymia, a rate similar to that found in Spanish study.[25]

Analysis of data confirmed the high rate of prevalence of lifetime of depression (17.7%) this seems closer to the results of two American studies.[2226]

A gender difference in the prevalence of depressive disorders was observed P = 0.01 OR 2.1 (1.09–4.3). In fact, women have a higher rate of MDE and dysthymia compared to men; which consistent with the literature.[27]

Our finding indicated that the GAF score was statistically significant lower among patients with depressive disorders, specifically patients with MDE and recurrent MDE. In a cross-sectional study evaluated the quality of life among 360 depressed patients;[28] they found that the score is altered in all its physical and mental dimensions. A second study,[29] carried out in China revealed that < 3% of depressed outpatients are satisfied with their health. Other studies and meta-analysis showed that depressive disorders are an important determinant of disability and quality of life in patients.[3031]

On multivariate analysis, we did not find a significant association this can be explained by the sample size, which was relatively smaller than that of other studies. Although it has been demonstrated that MDE was associated with female gender, substance use, unmarried status, and being unemployed.[2332]

Conclusion

The prevalence of depressive disorders, suicide risk, and the alteration of the quality of life among primary health care patients in Morocco, suggest the importance of identifying and treating this population, which implies the physician awareness of those disorders.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- High prevalence of mental disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:49-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression in primary care: Current and future challenges. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:442-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental health in Morocco, national survey on the prevalence of mental disorders and drug addiction. Encephale. 2007;33:125-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Do primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late-life depression?. A meta-analysis stratified by age. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:285-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of prolonged duration of untreated depression on antidepressant treatment outcome. J Affect Disord. 2013;145:42-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression in nursing home residents. Eur Geriatr Med. 2011;2:332-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Racial and ethnic differences in depression: The roles of social support and meeting basic needs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:41-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Moroccan colloquial Arabic version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): Qualitative and quantitative validation. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:193-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Axis V – Global Assessment of Functioning scale (GAF), further evaluation of the self-report version. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:575-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and disability burden among older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1325-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorder and personality factors associated with suicide in older people: A descriptive and case-control study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:155-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of common mental disorders in general practice attendees across Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:362-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aclinical prediction rule for detecting major depressive disorder in primary care: The PREDICT-NL study. Fam Pract. 2009;26:241-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Involving service users in the evaluation and redesign of primary care services for depression: A qualitative study. Prim Care Community Psychiatr. 2006;10:109-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1994;16:267-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: Prevalence and recognition. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:185-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of depression among patients and its detection by primary health care workers at Matawale Health Centre (Zomba) Malawi Med J. 2014;26:34-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of mental disorders in primary care: Results from the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care study (DASMAP) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:201-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:655-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- The point prevalence of depression and associated sociodemographic correlates in the general population of Latvia. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:104-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of depressive disorders in primary care practice in Spain. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34:21-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of and factors associated with current and lifetime depression in older adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1998;30:366-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression, anxiety, and somatoform disorders: Vague or distinct categories in primary care?. Results from a large cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:189-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depressive disorders and quality of life: A cross sectional study including 360 depressive patients followed at the psychiatry consultation of the Mahdia university hospital. Encephale. 2008;34:256-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in outpatients with depression in China. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:513-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;11:38-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1171-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression symptoms and associated socio-demographic factors in primary health care patients. Psychiatr Danub. 2015;27:31-7.

- [Google Scholar]