Translate this page into:

Cognitive Impairment among Persons of Rural Background Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection on Antiretroviral Therapy: A Study from a Tertiary Care Centre of North India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Vikram K. Mahajan, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy, Dr. R. P. Government Medical College, Kangra, Tanda - 176 001, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: vkm1@rediffmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is often accompanied by progressive neuropsychiatric manifestations varying between asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment, mood and personality disorders, psychosis, mild cognitive-motor disorder, and HIV-associated dementia (HAD).[12] Since it adversely affects adherence to medications, interact socially or ability to work, and employability, early recognition and management of individuals with HAD are important for improving quality of their life.[34] However, it remains understudied despite a significant prevalence of HIV/AIDS-affected Indian populations.[567]

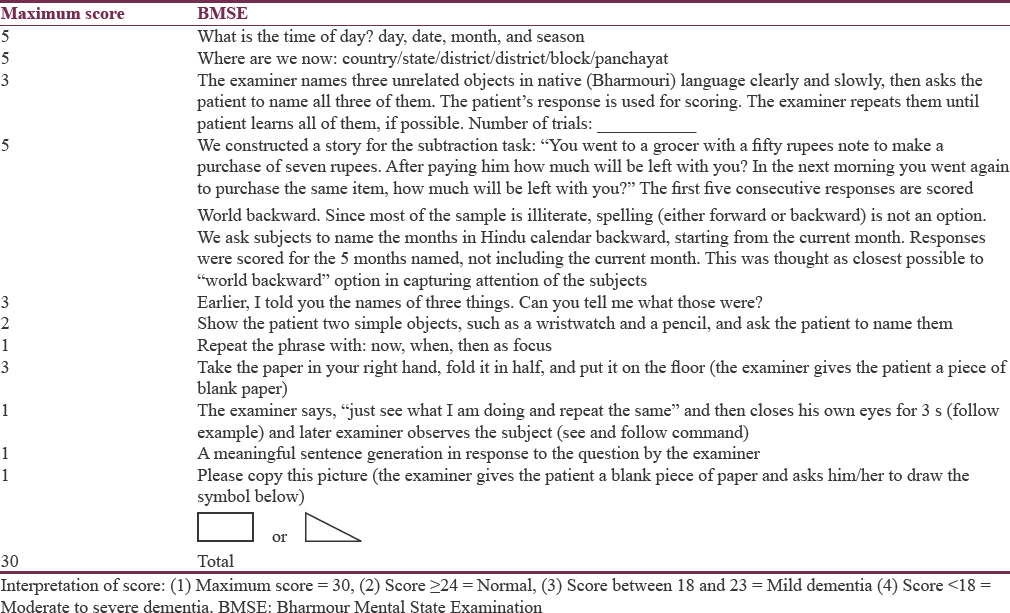

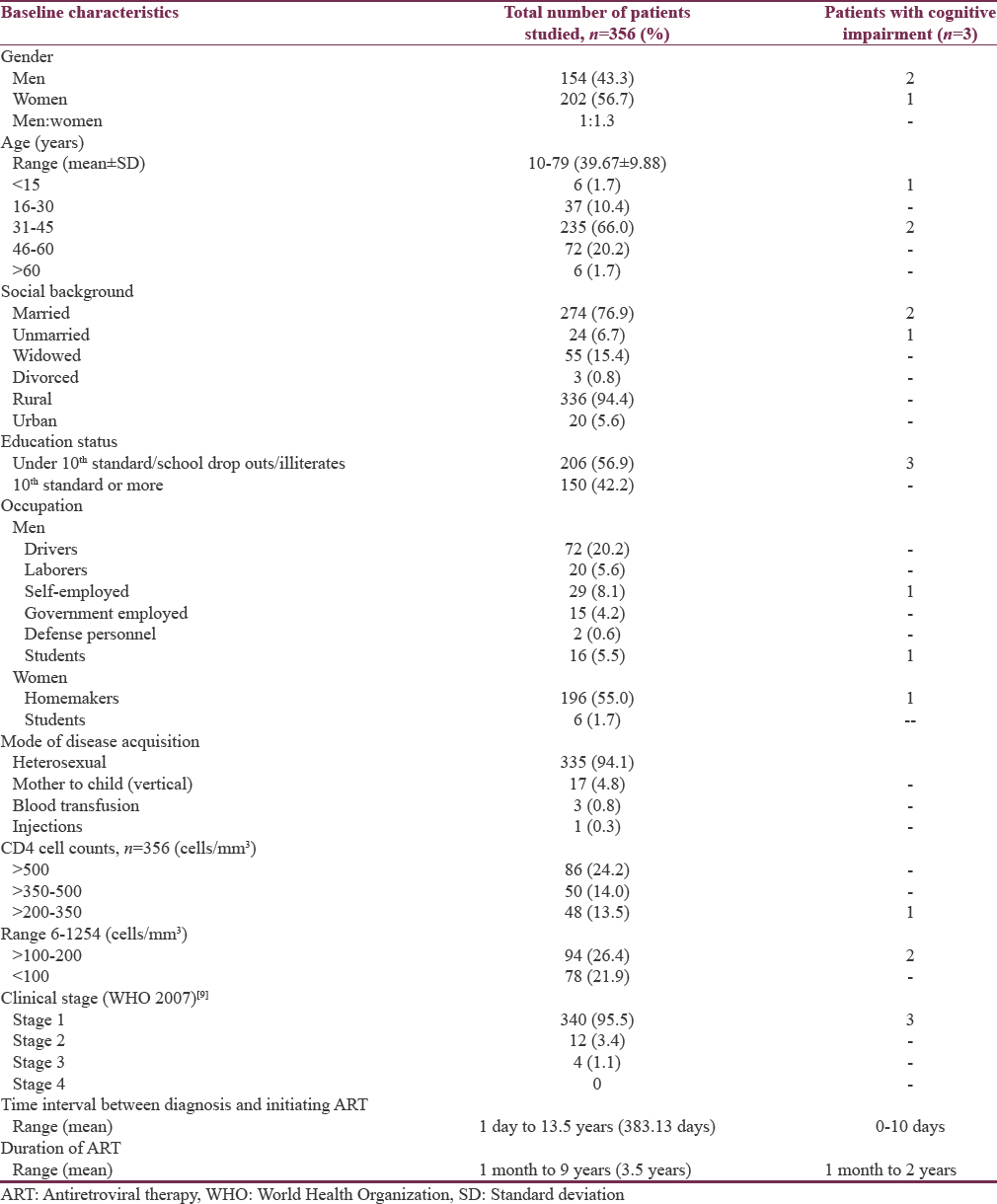

We studied 356 (male:female 154:202) HIV/AIDS-affected persons (old and new) aged 10–79 (mean ± SD = 39.67 ± 9.88) years between July 2015 and June 2016 presenting in the dermatology outpatient clinic and institutional antiretroviral therapy (ART) center. Their sociodemographic details, CD4 counts, and presence of any other illness were recorded from individual's highly active ART (HAART) records and clinical examination. All enrolled subjects completed a predesigned questionnaire with investigators’ help in their native language [Table 1]. This pretested questionnaire to suit Indian patients is structured for assessing the dementia status of HIV/AIDS-affected persons using Bharmour Mental State Examination (BMSE) scale.[8]

The clinicoepidemiologic profile of the study population [Table 2] was similar as reported previously[9] and comprised majority, 235 (66%) in 31–45 years age group. The 336 (94.4%) ruralites made the majority and 206 (56.9%) persons were either school dropouts, illiterate, or under matric. Most, 121 (34%), individuals were drivers, staying-alone laborers, and self-employed among males and 196 (55%) women were homemakers. The 22 (6.2%) children/adolescents (16 boys, 6 girls) aged 10–19 years were students. The mode of infection was heterosexual in 335 (94.1%) individuals. The majority, 340 (95.5%) persons, were in WHO stage-1 of HIV disease.[10] All (100%) were on regular HAART for 1 month to 9 (mean 3.5) years and CD4 counts ranged from 100 to 350 cells/mm3 in 142 (39.9%), >500 cells/mm3 in 136 (38.2%), and <100 cells/mm3 in 78 (21.9%) individuals, respectively.

Only 3 (0.8%) persons were identified having mild dementia/neurocognitive impairment on BMSE scale; a 10-year-old school-going boy (Score: 22), a 38-year-old self-employed man (Score: 22), and 31-year-old woman (Score: 23). They had WHO clinical stage-1 of the disease, were under matric, on regular HAART (tenofovir, efavirenz, lamivudine) for 6 months, 4 years, and 5 years, respectively, which was started a month after clinical diagnosis. They had CD4 counts of 173, 190, and 179 cells/mm3, respectively.

HAD, a phenotype of HIV-encephalitis, earlier known as AIDS dementia complex (ADC), is attributed to the virus-infected brain macrophages and activated microglia in the central nervous system. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder is the new definition for ADC and considered AIDS-defining illness. It was not uncommon having an estimated incidence of 10% before the introduction of HAART in 1996 but has decreased approximately by 50%, since then with an estimated prevalence of 21%–80% now.[111] Paradoxically, an increased prevalence of mild forms is being recognized more often than before.[212] However, the overall incidence and prevalence rates of HAD in the post-HAART era vary greatly by geography, treatment, and risk factors studied.[13] Old aged HIV + individuals are definitely at higher risk for HAD than HIV-seronegative individuals.[1415] High viral load during early stage, female gender, family history of dementia, depression, low educational level, unemployment, low CD4 counts (nadir CD 4 count 50 cells/mm3), anemia, systemic symptoms, and intravenous drug abuse are other identified risk factors for HAD in studies but included no Indian populations.[21116171819] Good education suggests a cognitive reserve and mind's resiliency to neuropathological damage while HIV/AIDS-affected individuals with lower cognitive reserve have demonstrated worse neuropsychometric performance.[19] This is also evident in our 3 (0.8%) patients with signs of mild HAD having low education status, the only identified risk factor in them. However, we did not study HIV viremia in them.

Although several screening tools have been used to identify cognitively impaired individuals in HIV outpatient clinics, the International HIV Dementia Scale remains popular internationally.[1415202122] Indian studies have also used similar scales;[67] however, being in English, it remains under-evaluated being poorly comprehensible by Indian patients. The BMSE scale in native language used by us was convenient and easily comprehended by studied subjects.

Despite small number of subjects, lack of HIV-seronegative controls, and no viral load studies, HAD/neurocognitive impairment does not seem uncommon even among individuals on HAART. However, our results may not represent other HIV/AIDS-affected populations for being limited period, single-center, cross-sectional study. Nevertheless, an early screening for neurocognitive impairment using a formal neuropsychometric battery and identification of risk factors in Indian subjects will help in planning of comprehensive health care envisaged in Phase-IV NACP for at-risk patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The help extended by all the staff members at ART Centre, Dr. R. P. Government Medical College, Kangra (Tanda), Himachal Pradesh, is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- HIV-associated dementia in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Microbes Infect. 2011;13:419-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurologic complications of HIV in the HAART era: Where are we? Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:373-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59:1944-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: Effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS. 2004;18(Suppl 1):S19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- NACO Annual Report 2012-2013. Department of AIDS Control. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi, India. 2013

- [Google Scholar]

- Study to assess the prevalence, nature and extent of cognitive impairment in people living with AIDS. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:149-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of neurocognitive functions in HIV/AIDS patients on HAART using the international HIV dementia scale. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2014;4:252-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a cognitive screening instrument for tribal elderly population of Himalayan region in Northern India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2013;4:147-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude, and perception of disease among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immuno deficiency syndrome: A study from a tertiary care center in North India. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2016;37:173-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2007. World Health Organization. WHO Case Definition of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIV-Related Disease in Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization; Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf

- Epidemiology of neurodegenerative diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:653.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurovirological correlation with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and encephalitis in a HAART-era cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62:487-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying risk factors for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders using the international HIV dementia scale. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:1114-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of cognitive reserve on neuropsychological functioning in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:148-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of age and HIV on neuropsychological performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:190-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) in Malawian adults and effect on adherence to combination anti-retroviral therapy: A cross sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98962.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for neurocognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety in HIV-infected patients in Western Europe and Canada. AIDS Care. 2014;26:1555-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with incident human immunodeficiency virus-dementia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:473-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- CD4 nadir is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25:1747-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- The international HIV dementia scale: A new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS. 2005;19:1367-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) in Sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Yaoundé-Cameroon. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285:149-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity of the international HIV dementia scale in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:95-101.

- [Google Scholar]