Translate this page into:

Cognitive, Behavioral, and Functional Impairments among Traumatic Brain Injury Survivors: Impact on Caregiver Burden

Manju Dhandapani, PhD National Institute of Nursing Education, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Sector 12, Chandigarh 160012 India manjuseban@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background The burden of cognitive, behavioral, and functional impairments after traumatic brain injury (TBI) is still not highlighted much, but its impact on caregivers is socio-economically relevant. The objectives of the study were to assess cognitive, behavioral, and functional impairments in patients of TBI and its impact on caregiver burden.

Materials and Methods A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using a total enumeration sampling technique. Mini-mental status examination, neuropsychiatric inventory and Rappaport’s disability rating scale were used to assess patients’ cognitive, behavioral, and functional impairments, respectively. Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale was executed to quantify the caregiver burden.

Results Fifty patients of TBI and their caregivers were enrolled. Among these, 24% had moderate cognitive impairments. Among behavioral symptoms, 40% had agitation, 24% had depression, 18% had anxiety, and 16% had irritability. Moderate functional disability was reported by 18% of the patients, while 2% reported severe functional disability. Moderate to severe caregiver burden was reported by 8% of caregivers. Patients’ behavioral (r = 0.507, p < 0.001), functional (r = 0.473, p = 0.001), and cognitive (r = –0.438, p = 0.001) impairments had significant correlations with caregiver burden.

Conclusion Patients develop cognitive, behavioral, and functional disability after TBI. The caregiver burden increases significantly with cognitive dysfunction, behavioral symptoms, and impaired functional status of patients. Therefore, appropriate support is to be provided to caregivers as well as patients.

Keywords

traumatic brain injury

caregiver burden

disability rating scale

behavioral changes

outpatient department

rapport disability rating scale

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the foremost causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide. It is a threat to the global economy as well.1 2 Similar to other neurological and neurosurgical illnesses, TBI may result in cognitive, behavioral, and functional disability and hence may result in caregiver burden in all socio-economic classes.3 4 Cognitive deficits often reported by the survivors of TBI may affect the continuous rehabilitative and therapeutic process and affect the activities of daily living as well as the quality of life of the survivors.5 6 7 The burden of cognitive, behavioral, and functional impairments after TBI is still not highlighted much, but its impact on caregivers is socio-economically relevant.6

Though TBI can impact all cognitive domains, it most often affects attention, processing speed, learning, memory, and executive functions. Along with physical and functional disability, cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms play a major role in long-term morbidity in TBI survivors.7 8 9 Depression and anxiety are often seen in TBI survivors even after discharge from hospital.9 Emotional symptoms such as depression or anxiety make the patient feel their injury and disability more severe and results in a higher functional disability. Cognitive deficits and speech impairment in TBI can cause communication problems which can make the patient more stressed and dependent on caregivers. They express difficulty in thinking of the right word, misunderstand the meaning of words or sentences.10 Behavioral symptoms in TBI survivors adversely affect the progress in recovery. The behavioral problems range from emotional liability, depression, hyperactivity, anger, sensual inappropriateness, and elopement. Behavioral problems of the patients can lead to poor co-operation and reduced participation in their activities of daily living. Behavioral symptoms depend upon the lobe that gets injured. Functional problems faced by TBI survivors that affect rehabilitation and personal or social life include difficulty in walking, voiding, feeding, and inability to self-care.11 12 13

TBI recovery and outcomes generally affect the caregiver’s well-being and can lead to caregiver burden. The caregiver burden is stress, which is perceived by caregivers due to the patient’s chronic illness or disabilities during the home care situation. The course of recovery after a TBI can be lengthy and challenging equally for the survivor and family caregiver. Caregivers habitually ignore their health as well as family and work responsibilities during the acute care, hospital stay, and follow-up of the patient. They may have struggles in resuming to preinjury functional level as the home care of patients with TBI is time-consuming and laborious. At home, the caregivers are responsible for providing the bulk of care, and they can sense changes in psychological and physical well-being. The adverse effect of these changes may be proportional to the TBI severity, recovery process, outcome, survivor’s care needs, family adaptation, and social or family support. Existing literature has reported that family caregivers than TBI survivors may experience more distress. Emotional symptoms in caregivers such as anxiety or depression and its adverse effects may stay longer in their life.14 15 16 17 18 Hence, we have undertaken this study to assess the impact of the cognitive, behavioral, and functional status of TBI survivors and burden among their caregivers.

Materials and Methods

We have conducted a cross-sectional study by means of a total enumerative sampling method on 50 TBI survivors and their caregivers attending the Neurosurgery outpatient department in a tertiary level health care institute in North India during a period of 6 months with data collection from April to June 2018. We have obtained ethical clearance from the Institute Ethics Committee. All adult patients suffering from TBI were recruited from 3 months to 2 years after the initial TBI. Patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14 to 15 on their outpatient department visit were enrolled along with their primary family caregivers, i.e., the family member who was directly involved in the care of the patient. Consent was taken from conscious patients (GCS 15) and caregivers after explaining the objectives of the study and the confidentiality of the data was ensured. As the patients of GCS 14 are having some degree of impairment in consciousness, consent was taken from the family caregiver. We excluded patients and caregivers with a communication deficit.

Instruments

We used the mini-mental status examination (MMSE) which is a short and simple tool to measure the cognitive function of patients. It helps the assessment and screening of cognitive function of the hospitalized patients as well as the follow-up patients. It evaluates the cognitive functions including orientation, memory, concentration, recall, linguistic, registration, and the ability to perform simple instructions. The scoring of MMSE is from 0 to 30, where lower the score higher the degree of cognitive impairment. A score of 24 or more describes the normal cognition and the cognitive deficit is graded based on the score as mild (20–25), moderate (10–19), or severe (≤9).19

We used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) to quantify the number of behavioral changes in the patients. It assesses 12 symptoms of behavioral disturbances in patients including delusion, hallucination, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, agitation/aggression, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/liability, motor disturbance, nighttime behaviors, and appetite or eating disorders. As the NPI score increases behavioral symptoms also increase. To identify behavioral symptoms, we interviewed the family caregiver who stays with the patient and knows the patient’s behavioral changes. The NPI-Q was administered to the caregiver in the absence of the patient. NPI-Q is a simple tool with high reliability as well as validity.20

Rappaport disability rating scale (DRS) was executed to estimate the functional status, impairment, disability, and handicap of the patients.21 The score ranges from zero to 29, where zero designates no disability and 29 designates complete extreme vegetative state or death. As the DRS score increases, functional disability also increases.

Zarit caregiver burden scale contains 22 questions based on the psychological domain of caregivers and examines the burden associated with disability, emotional disturbances, and home care needs of the patients. The scale consists of a five-point Likert scale where the caregiver is asked to report each item from “never” to “nearly always present.” The score ranges from 0 to 88, and a higher score signals higher caregiver burden.22

The severity of TBI was graded through admission GCS score of the patient where the GCS between 13 and 15 is considered as mild TBI, GCS between 9 and 12 as moderate, and GCS between 3 and 8 as severe.23

We used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 20.0) for data analysis. The independent t-test was used to compare the caregiver burden with and without the presence of each behavioral symptom in the patients. Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the linear relation of caregiver burden with MMSE score, NPI-Q score, and DRS score. Two-tailed tests were used and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical profiles of the TBI survivors are presented in Table 1. Out of 50, 32 (64%) of the patients were less than 40 years of age. The mean age of patients was 36.23 ± 12.21 years, with the range of 19 to 67 years and 76% of the patients were males. The majority of them (80%) were married, 60% of the patients had education up to 10th class, 44% of patients were nonskilled employees, and 36% were unemployed. The mean per-capita income was ₹ 3,616.23 ± 1,097.72 with a range of ₹ 500 to 20,000. For 66% of the patients, duration since injury was 3 to 6 months. TBI was due to road traffic injury in 86% of the patients; 48% of the patients suffered severe TBI followed by moderate TBI in 36%.

|

Characteristics of patients |

(n = 50) |

|---|---|

|

Mean ± SD or f (%) |

|

|

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury; SD, standard deviation. |

|

|

Age (y) |

36.23 ± 12.21 |

|

Up to 40 |

32 (64) |

|

41–60 |

10 (20) |

|

>60 |

8 (16) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Male |

38 (76) |

|

Female |

12 (24) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

Unmarried |

10 (20) |

|

Married |

40 (80) |

|

Educational status |

|

|

Illiterate |

8 (16) |

|

Up to 10 |

31 (62) |

|

Senior secondary |

7 (14) |

|

Graduate |

4 (8) |

|

Occupation |

|

|

Skilled employee |

10 (20) |

|

Nonskilled employee |

22 (44) |

|

Unemployed |

18 (36) |

|

Monthly per capita income (₹) |

3,616.23 ± 1,097.72 |

|

≤5,000 |

43 (86) |

|

>5,000 |

7 (14) |

|

Duration since TBI |

|

|

3 to 6 mo |

33 (66%) |

|

6 mo to 1 y |

9 (18%) |

|

>1 y |

8 (16%) |

|

Mode of injury |

|

|

Fall from height |

5 (10%) |

|

Road traffic accident |

43 (86%) |

|

Violence |

2 (4%) |

|

Severity of TBI (Admission GCS) |

|

|

Mild (13–15) |

8 (16%) |

|

Moderate (9–12) |

18 (36%) |

|

Severe (3–8) |

24 (48%) |

Table 2 shows the socio-demographic profile of caregivers. The caregivers’ mean age was 37.51 ± 13.82 years. Parents (20%) and spouses (20%) consisted of almost half of the caregivers. Nearly two-thirds of the family caregivers (62%) were female and more than three-fourths of the caregivers (80%) were married. Nearly half of the family caregivers were unemployed and below the poverty line (54%). Half of the caregivers were educated up to 10th class. The majority of the caregivers were healthy.

|

Characteristic of caregivers |

(n = 50) |

|---|---|

|

Mean ± SD or f (%) |

|

|

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

|

|

Age (y) |

37.51 ± 13.82 |

|

Up to 40 |

30 (60) |

|

41–60 |

12 (24) |

|

>60 |

8 (16) |

|

Relation with patient |

|

|

Spouse |

10 (20) |

|

Parents |

10 (20) |

|

Siblings |

8 (16) |

|

Children |

6 (12) |

|

Other |

16 (32) |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

31 (62) |

|

Male |

19 (38) |

|

Occupation |

|

|

Skilled employee |

8 (16) |

|

Nonskilled employee |

15 (30) |

|

Unemployed |

27 (54) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

Unmarried |

10 (20) |

|

Married |

40 (80) |

|

Family type |

|

|

Joint |

24 (48) |

|

Nuclear |

26 (52) |

|

Educational status |

|

|

Illiterate |

3 (6) |

|

Up to 10th standard |

25 (50) |

|

Senior secondary |

15 (30) |

|

Graduate |

7 (14) |

|

Self-reported health status |

|

|

Healthy |

48 (96) |

|

Unhealthy |

2 (4) |

|

Having helper at home |

|

|

Yes |

8 (16) |

|

No |

42 (84) |

Cognitive Dysfunction of Patients with TBI

Cognitive dysfunction based on the MMSE score of the patients is shown in Fig. 1. Out of 50 patients, 64% of the patients were found to have normal cognition (MMSE score 24–30), but 24% had moderate, and 12% had mild cognitive dysfunction.

-

Fig. 1 Level of cognitive dysfunction of patients based on MMSE. MMSE, mini-mental status examination.

Fig. 1 Level of cognitive dysfunction of patients based on MMSE. MMSE, mini-mental status examination.

Behavioral Symptoms of Patients with TBI

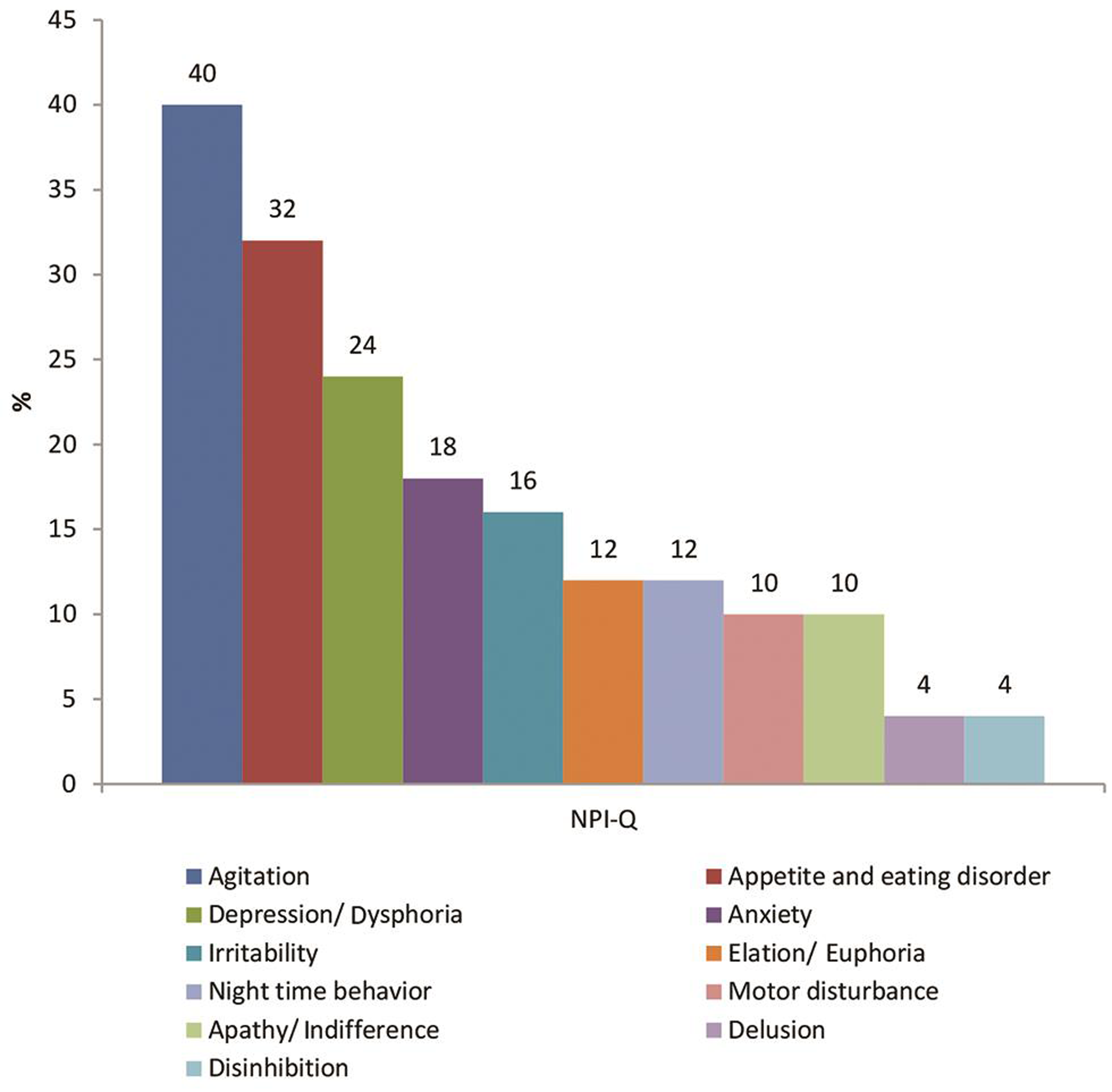

Behavioral symptoms of patients with TBI based on NPI-Q is depicted in Fig. 2. Out of 50 patients, 40% had agitation, 32% had appetite disturbance, 24% had symptoms of depression, 18% had anxiety, and 16% had irritability. None of the patients had hallucination. Very few patients had problems of elation, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, and motor disturbances.

-

Fig. 2 Behavioral symptoms of patients based on Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI).

Fig. 2 Behavioral symptoms of patients based on Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI).

Functional Impairment/Status of the Patients with TBI

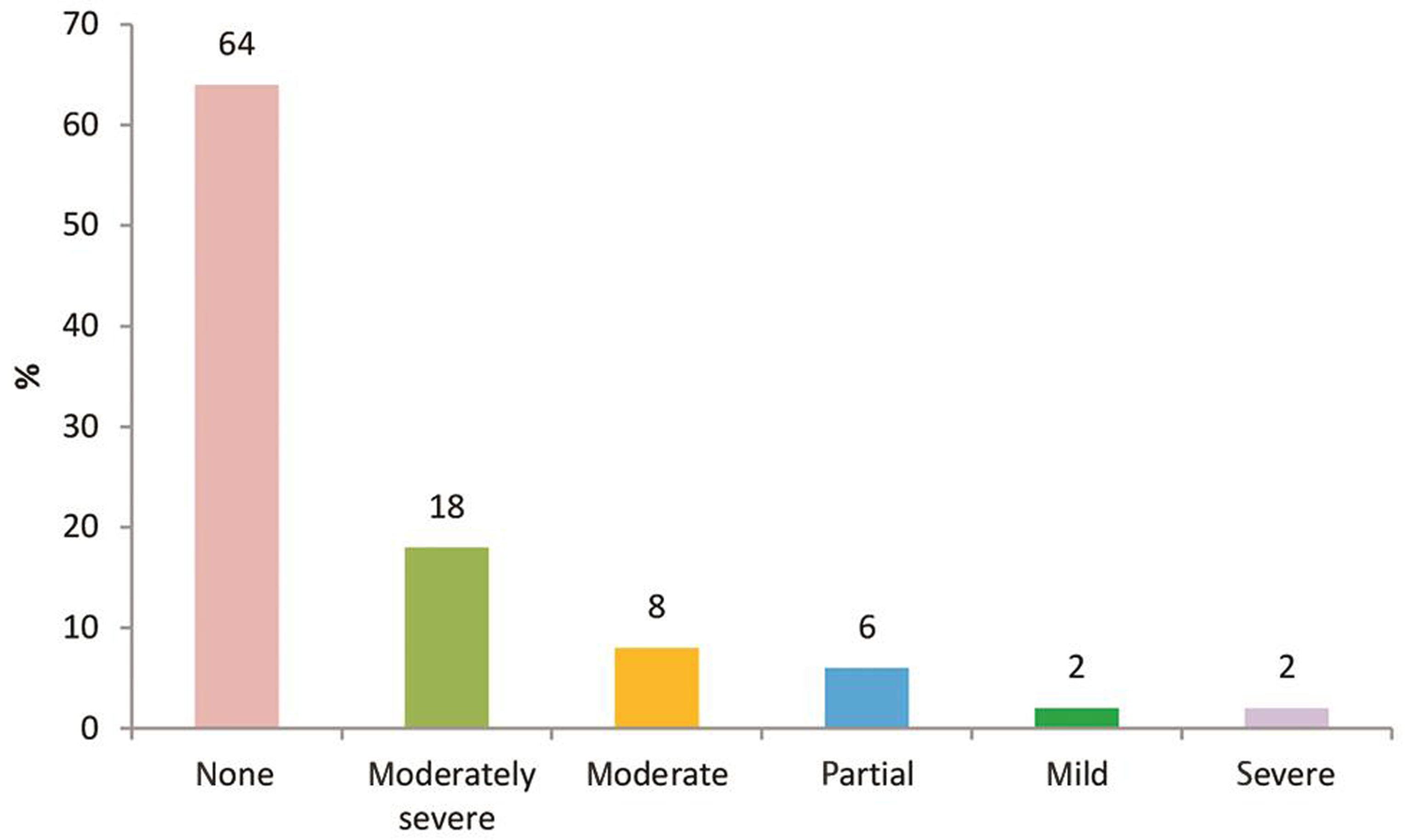

Fig. 3 shows the functional status of patients based on the DRS score (rapport disability rating scale of the patients). Out of 50 patients, 64% of the patients did not have any disability, but 18% had moderately severe, 8% had moderate, and 6% had a partial type of disability. Only 2% of the patients had a mild and severe type of disability.

-

Fig. 3 Functional status of the patients based on Rappaport disability scale.

Fig. 3 Functional status of the patients based on Rappaport disability scale.

Burden among Caregivers

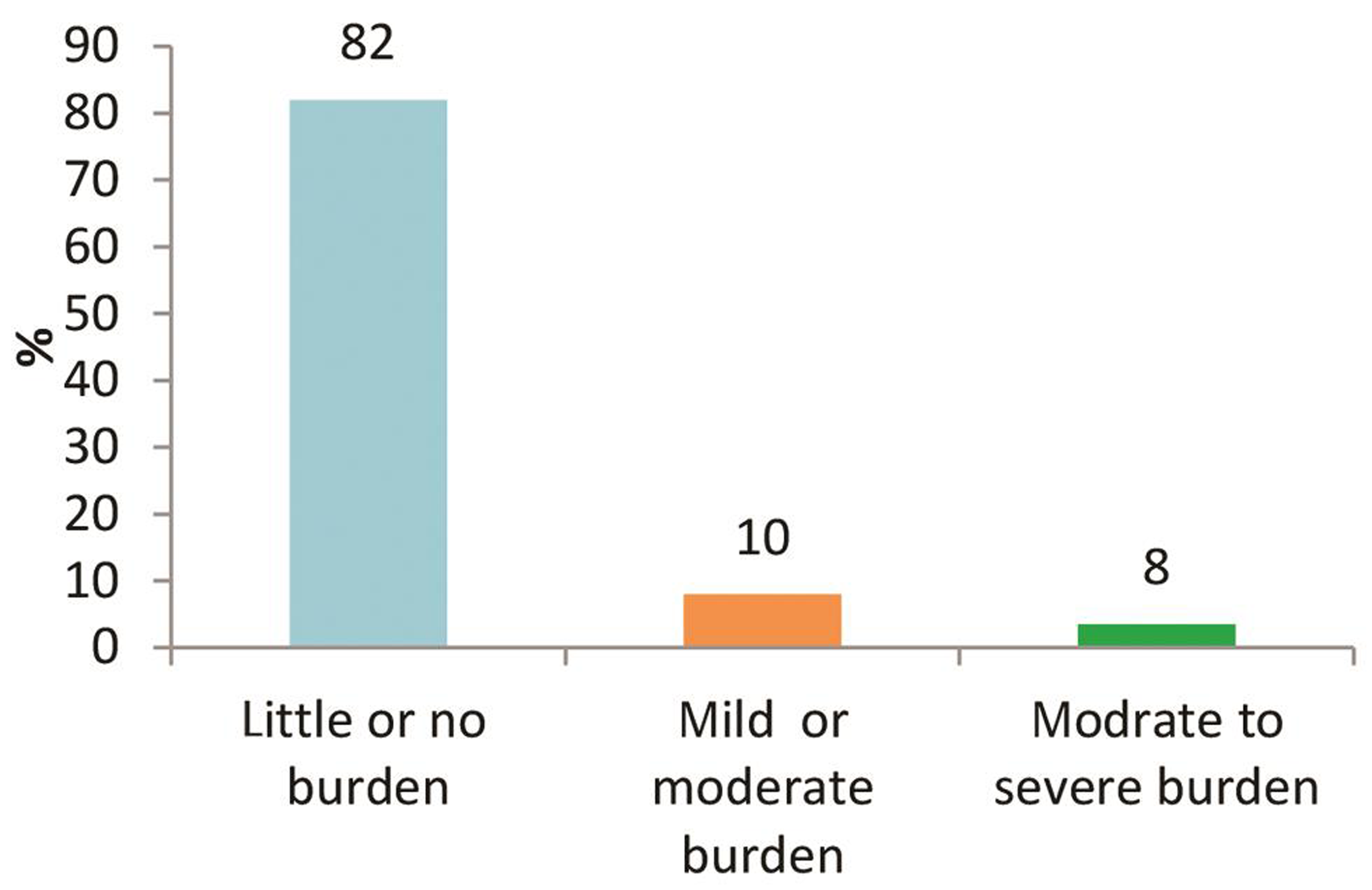

Figure 4 depicts the burden of caregivers based on the Zarit caregiver burden scale. It shows that 82% of the caregivers had little or no burden, 10% of the patients had moderate to severe burden and 8% had a mild to moderate burden.

-

Fig. 4 Caregiver burden based on Zarit caregiver burden scale.

Fig. 4 Caregiver burden based on Zarit caregiver burden scale.

Impact of Patient’s Cognitive, Behavioral, and Functional Impairment on Caregiver Burden

Correlation co-efficient between patient’s cognitive, behavioral as well as functional impairment and caregiver burden was calculated to assess their influence on caregiver burden. As shown in Table 3, the significant negative correlation between cognition score and caregiver burden score (r = –0.44, p = 0.001) shows increased caregiver burden with impairment in the cognitive function of the patient. Similarly, the significant positive correlation between NPI-Q score and caregiver burden score (r = 0.51, p < 0.001) indicates more caregiver burden with an increasing number of behavioral symptoms. The caregiver burden did not show any association with each behavioral symptom assessed. The significant positive correlation between DRS and caregiver burden (r = 0.47, p = 0.001) depicts higher caregiver burden with the increasing level of disability.

|

Patient’s variable |

Caregiver burden score “correlation coefficient (r)” |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: DRS, disability rating scale; MMSE, mini-mental status examination; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire. a p-value < 0.05. |

||

|

MMSE score |

–0.44 |

0.001a |

|

NPI-Q score |

0.51 |

<0.001a |

|

DRS score |

0.47 |

0.001a |

Discussion

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study to assess cognitive-behavioral and functional impairments in patients of TBI and its impact on caregiver burden. Though patients of TBI have good recovery,24 many live with some degree of cognitive, behavioral, and functional impairment.25 26 Using the total enumeration sampling technique, we enrolled 50 patients along with their family caregivers. Appropriate standardized tools were used for data collection. The present study showed that caregivers suffer the burden of a different level while caring for patients of TBI at home. The caregiver burden is linked with cognitive dysfunction, behavioral symptoms, and functional impairment of the TBI survivor.

The data analysis of the study revealed that 36% of our patients had mild to moderate cognitive impairment as compared with a prevalence of 21 to 25% reported in the literature.25 Literature shows that there are initial and persistent cognitive deficits in patients of TBI.8 Similarly, it is also reported that TBI results in a severe deficit in processing information, attention, short-term memory, executive functions, and remote memory.7 24 25 26

In the present study, common behavioral changes present in the patients of TBI included agitation, appetite and eating disorders, depression, anxiety, and irritability. As compared with 14% reported by de Guise et al, agitation was found in 40% of our patients. Disinhibition was reported by 4% of our patients which was in line with 10% reported in literature.25 Depressive symptoms such as dysphoria, anxiety, and irritability were present in approximately 20% of the patients as compared with 25 to 40% of the patients reported in the literature.9 27 Prevalence of behavioral symptoms up to 80% is reported in patients recovered after severe TBI.9 Patients of TBI may suffer from persistent behavioral problem that prolongs to later period of life.9 Similarly, a decline in behavioral status is seen as compared with the preinjury state in social integration, productivity, and home instigations. Approximately one-fourth of the patients suffer from social and emotional problems.27 28 29

As per literature, cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and physical impairment is common in patients of TBI. The cognitive and behavioral impairments could be due to the sequelae of the complex cascade of microvascular ischemia, proportional to the severity of TBI.3 15 16 30 31 32 The damage to the key pathways of cognitive function due to white matter damage is vastly related to cognitive impairment in patients of TBI.33

In the present study, approximately 35% of the patients have reported varying degrees of disability which is slightly lesser compared with more than 40% reported in previous literature.12 34 Functional disabilities of the patients were found to be affecting the daily activities such as feeding difficulties and employment status. In our patients, only 4% of the patients were employable while 24% of patients were not employable for the jobs they were already performing. Previous studies show that patients do suffer disturbed functional status following TBI. Limited range of motion, pain, swelling, and erythema were the main consequences of TBI. Other associated injuries such as spinal cord or peripheral nerve injuries, fractures and amputations can also be the cause of functional disabilities in patients.9 12 34 Functional impairment is also related to depressive signs in patients of TBI.9

The family caregivers of patients with TBI in our study reported a certain level of burden due to lack of time, stress while giving care, financial burden, etc.; approximately 20% of caregivers suffered varying degrees of burden. Similar to present study findings, previous literature also shows that caregivers of patients with TBI suffer from significant levels of impairment in social adjustment, anxiety, and depression.14 Literature reports up to 50% prevalence of burden among caregivers of severe TBI.35 Few contributing factors to caregiver burden include lack of support, lack of time, unawareness, financial burden, emotional challenges, coping and other consequences of TBI.1 14 35 36

More than 80% of caregivers in our study suffered little or no burden which was contradictory to the previous report of 16 to 34% of caregivers of patients with TBI suffering burden.18 The less prevalence of burden among caregivers in our study could be because of the inclusion of TBI survivors with GCS 14 or 15. Hence, the burden experienced by caregivers in our study might not be generalized to caregivers of patients with TBI who continue to remain dependent or unconscious. Burden experienced by the caregivers is multifactorial and also is influenced by functional as well as the behavioral status of the patients.6 35 It is evident that the functional status of patients with GCS 14 or 15 is better compared with patients with lesser GCS. The less prevalence of burden also could be due to positive coping strategies used by the caregivers. Literature has reported that caregivers use several adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies to cope with the patients’ illness.17 Consulting doctors, talking to friends/family members, seeking practical help and denial were commonly used coping strategies by the caregivers.17 37 However, the burden experienced by the caregivers of TBI or other neurological illnesses may be higher in developing countries like India due to the poor support system, inadequate use of hospital services, home care strategies, and rehabilitation facilities.38 39

Our study also has found an adverse impact of the cognitive-behavioral and functional impairment of the TBI survivors on caregiver burden. Managing patients with behavioral symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and irritability is a stress-inducing task for the caregivers. They may have to spend extra time and energy on taking care of patients with behavioral changes. Based on the dependability of the patients, caregivers also have to provide the necessary assistance or support to the patient for meeting the activities of daily living. The present study also has identified the dependency of patients in activities such as feeding, toileting, bathing, dressing, and transferring. Contrary to the finding of Sherwood et al in 2004,16 we have elicited the relation between functional deficit and burden among caregivers. Pinquart and Sörensen in 2004 also had reported the relation between functional impairment of the patients and the poor well-being of the caregivers.6 Similar to our finding, cognitive dysfunction is found to be associated with caregiver stress in other caregiving populations.6 29

Our study suggests that patients of TBI must be assessed for cognitive, behavioral, and functional deficits during follow-up to facilitate appropriate rehabilitation. Patients with cognitive and behavioral impairment may benefit from individualized cognitive behavioral therapy.32 Nurse-led assessment and brief counseling of the patients are proven to be effective in neuropsychological rehabilitation32 and can aid to overcome the underutilization of neurorehabilitation services in developing countries like India.40 The caregivers require constant support and empowerment to overcome the challenges they face. The impact of patients’ cognitive, behavioral, nutritional and functional status on neurological outcome and caregiver burden prompt the health care professionals to carefully look into these aspects of the patients with TBI so that appropriate therapies can be initiated.8 41 It will also help to alleviate caregiver burden and improve the quality of life of TBI survivors and their family caregivers.

We had directly interviewed patients and caregivers with the help of selected standardized tools. The cognitive and functional status of the patients was evaluated directly using appropriate tools rather than trusting on caregivers’ observation or perception. Further studies can be conducted to assess the effectiveness of specific cognitive, behavioral, and rehabilitative interventions on improving the cognitive, behavioral, and functional deficits of patients with TBI and to assess the coping strategies among their caregivers.

Conclusion

TBI survivors do suffer cognitive, behavioral, and functional dysfunctions after injury. During the provision of care, caregivers suffer the burden of different levels. The caregiver burden is significantly increased with cognitive dysfunction, behavioral symptoms, and impaired functional status of the patients with TBI. Nurses or other health personals can be of ideal support by providing maximum aid and help by being guides, counselors, and health educators to both patients as well as caregivers.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(8):728-741.

- [Google Scholar]

- The economic divide in outcome following severe head injury. Asian J Neurosurg. 2012;7(1):17-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and trends in the neuropsychological burden of patients having intracranial tumors with respect to neurosurgical intervention. Ann Neurosci. 2017;24(2):105-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive problems after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(1):179-180.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations of caregiver stressors and uplifts with subjective well-being and depressive mood: a meta-analytic comparison. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(5):438-449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive outcome following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(6):430-438.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders and functional disability in outpatients with traumatic brain injuries. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(10):1493-1499.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family caregiving of individuals with traumatic brain injury in Botswana. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(6):559-567.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing the quality of life in traumatic brain injury: Tunisian experience. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:e136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of functional and professional outcomes in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:e134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with remission of post-traumatic brain injury fatigue in the years following traumatic brain injury (TBI): a TBI model systems module study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(7):1019-1030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiver outcomes and interventions: a systematic scoping review of the traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury literature. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(1):45-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Independent impact of plasma homocysteine levels on neurological outcome following head injury. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;41(2):513-517.

- [Google Scholar]

- Forgotten voices: lessons from bereaved caregivers of persons with a brain tumour. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2004;10(2):67-75, discussion 75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coping among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(1):5-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting caregiver burden 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective nationwide multicenter study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(6):411-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disability rating scale for severe head trauma: coma to community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63(3):118-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment and prognosis of coma after head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1976;34:45-55. (1-4)

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological study of traumatic brain injury cases in a trauma centre of New Delhi (India) J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2015;8(3):131-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overview of traumatic brain injury patients at a tertiary trauma centre. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005;32(2):186-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inattentive behavior after traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1996;2(4):274-281.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and symptom rates of depression after traumatic brain injury: a comprehensive examination. Brain Inj. 2001;15(7):563-576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pain perception following different neurosurgical procedures: a quantitative prospective study. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52(4):477-485.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of distress in caregivers of persons with a primary malignant brain tumor. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(2):105-120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mild traumatic brain injury: a neuropsychiatric approach to diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(4):311-327.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in cognitive dysfunction following surgery for intracranial tumors. Surg Neurol Int. 2016;7(07):S190-S195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial tumors: a nurse-led intervention for educating and supporting patients and their caregivers. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(3):315-323.

- [Google Scholar]

- White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2011;134:449-463. (Pt 2)

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of long-term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States, 2003. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2008;23(2):123-131.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of caregiver depression among community-residing families living with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2007;22(1):3-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiver burden during the year following severe traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24(4):434-447.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospective comparison of simple suturing and elevation debridement in compound depressed fractures with no significant mass effect. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2015;157(2):305-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res. 2002;24(1):24-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of utilization of rehabilitation services among stroke survivors. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2018;9(4):461-467.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of trends in anthropometric nutritional indices and the impact of adiposity among patients of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology India. 2015;63(4):531.

- [Google Scholar]