Translate this page into:

Caregiver Burden among Caregivers of Mentally Ill Individuals and Their Coping Mechanisms

Address for correspondence: Dr. Varalakshmi Chandrasekaran, Department of Community Medicine, Melaka Manipal Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India. E-mail: varalakshmi.cs@manipal.edu

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

During a given year, almost 30% of the people around the world are affected by mentally ill health. In India, it accounts for about 20%. Caregivers face a lot of strain, ill health, and disrupted family life, with literature suggesting an increasing concern about their ability to cope up. The needs of caregivers of the mentally ill are given low priority in the current health-care setting in India.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to assess the burden of caregivers of mentally ill individuals and their coping mechanisms.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was employed with a quantitative approach. A convenient sample of 320 caregivers was taken from two private tertiary care centers and one public secondary care center in Udupi taluk. This study was conducted using the Burden Assessment Schedule (BAS) and Brief Cope Scale (BCS). Statistical analysis was done on categorical variables, and they were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were measured using mean and standard deviation. Univariate and multivariate analysis using binomial logistic regression was done. SPSS version 15 was used to analyze the data.

Results:

According to BAS, severe burden accounted for 40.9% and moderate for 59.1%. The highest amount of burden was seen in the areas of physical and mental health, spouse related, and in areas of external support. The BCS showed that the most frequently used coping styles were practicing religion, active coping, and planning.

Conclusion:

This study concluded that caregivers of the mentally ill individuals do undergo a lot of burden. Hence, there is a need to develop strategies that can help them such as providing them with a support structure as well as counseling services.

Keywords

Burden

caregiver

coping

mental illness

INTRODUCTION

Health especially, mental health, is one of the most important possessions of an individual and it needs to be cherished, promoted, and conserved to the maximum.[1] Around 450 million people worldwide are suffering from some mental or behavioral disorder according to the WHO, of which schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and alcohol use disorders are important causes for years lived with disability.[2] According to the evidence available, in India, about 190–200/1000 population have a psychiatric or mental disorder, this accounts for about 20% of the whole population. The major issues faced in India regarding mental health are lack of mental health workforce, financial aid, stigma, and caregiver burden.[3]

The family plays a very vital role in the care of a mentally ill patient. A caregiver has been defined as “a family member, who has been staying with the patient for more than a year and has been closely related with the patient's daily living activities, discussions, and care of health.”[4] Caregivers often have to sacrifice their own wants and undertake a lot of stress and are very much ignored. Caregiving drains one's emotions and hence caregivers undergo a lot of depression as compared to the general population.[5] The WHO states caregiver burden as “the emotional, physical, financial demands and responsibilities of an individual's illness that are placed on the family members, friends, or other individuals involved with the individual outside the health-care system.”[4] It includes taking care of personal hygiene of the patient and emotional support such as listening, counseling, giving company, and informational caring such as how to alter the living environment of the patient.[6]

Caring for people having a severe psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or a bipolar disorder creates a challenge for caregivers.[7] Due to the increasing demands and responsibilities, there is an increasing concern about their ability to manage or cope up.[7] Coping has been defined as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the specific external or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.”[7]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting

The present cross-sectional study was conducted between January 2016 and June 2016 in two private tertiary care centers and one public secondary care center located in Udupi taluk. Udupi district lies at the southern coastal belt of Karnataka state. Udupi district is divided into three taluks, namely, Udupi, Kundapura, and Karkala. Primary caregivers, who were family members, more than 18 years of age, male or female, who were able to read and write English or Kannada and had been living with the mentally ill patient for more than a year, and were closely associated with the patient's daily activities were included in the study. Those with a known diagnosis of mental illness and caregivers who were home nurses were excluded from the study. Of the eligible population, 320 participants were sampled using the convenience sampling method. In addition, thirty declined participation.

Convenience sampling technique was used to obtain the sample. Appropriate ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of a tertiary care hospital and measures were undertaken to maintain confidentiality of caregivers throughout the study and also during the analysis of data. All participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after the consent form was read by the participants. The consent form was in Kannada, the local language and in English, and it stated that the participation was completely voluntary and that the participant could withdraw at any time from the study. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study. During data collection, each person was identified by giving them a unique identification number. The participant was required to enter their name only while signing for written consent.

Study tools

Burden Assessment Schedule

The burden was assessed using a 40-item Burden Assessment Schedule (BAS)[8] developed by SCARF. The questionnaire was self-administered. The BAS questionnaire consisted of basic demographics and questions pertaining to certain components such as spouse related, physical and mental health, external support, caregivers routines, support of the patient, taking responsibility, other relations, patients behavior, and caregivers strategy.

Each question had three options such as “Not at all,” “To some extent,” and “Very much.” The participants had to choose any one of the options for each of the questions. Four questions were only to be answered if the spouse was the ill member. The minimum score of the scale was 40 and maximum was 120. According to this scale, the burden is classified into mild burden (0–40), moderate burden (41–80), and severe burden (81–120).

Brief Cope Scale

The 28-item Brief Cope scale (BCS) was used to assess the coping. The Brief COPE is comprised of 14 scales, each of which assesses the degree to which a respondent utilizes a specific coping strategy. These scales include: (1) active coping, (2) planning, (3) positive reframing, (4) acceptance, (5) humor, (6) religion, (7) using emotional support, (8) using instrumental support, (9) self-distraction, (10) denial, (11) venting, (12) substance use, (13) behavioral disengagement, and (14) self-blame.

Respondents’ rate items on a 4-point Likert scale such as 1 never does it, 2 does it a few times, 3 does it mostly but not always, and 4 does it always. Each of the 14 scales is comprised of 2 items; total scores on each scale range from 2 (minimum) to 8 (maximum). Higher scores indicate increased utilization of that specific coping strategy. Total scores on each of the scales are calculated by summing the appropriate items for each scale. The translations of both the scales were done in Kannada.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions. Mean, standard deviation, and range were calculated for all continuous variables including nine domains of BAS and 14 domains of BCS. After univariate analysis, the variables, which had significant P values, were taken for multivariate analysis to adjust for confounding variables. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals using the binomial logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

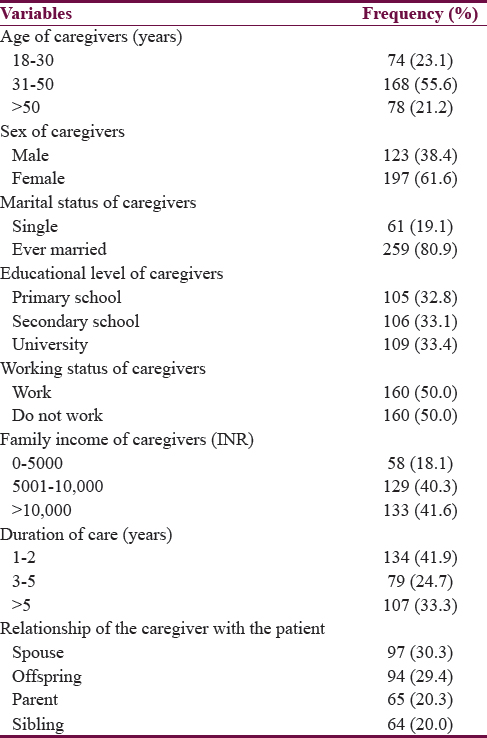

In this study, the majority of the caregivers were in the productive age group of 31–50 years (55.6%), were female (63.6%), ever married (80.9%), had completed their education up to university level (33.4%), had a family income in the range of INR 5001–10,000 (40.3%), provided care for mentally ill dependents for a period of 1–2 years (41.9%), and 30% were the spouse of those who were mentally ill individuals. About half of them worked. Caregivers in the age group of 18–30 years made up 23.1% and those above 50 years made up for 21.2%. Male caregivers made up for 38.4% and 19.1% of them were single. Of all caregivers, 32.8% had attended primary school and 40.3% belonged to the income category of INR 50,001–10,000. A third of the caregiving participants provided care for more than 5 years. Parents made up 20.3% of caregivers [Table 1].

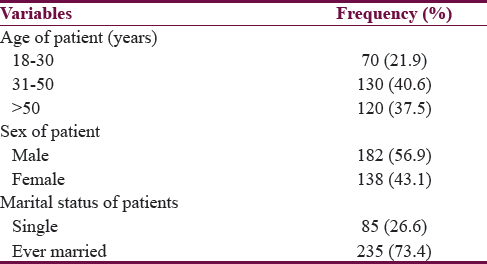

Most of the patients belonged to the productive age group of 31–50 years (40.6%), male patients (56.9%), and were ever married (73.4%). Female patients accounted for 43.1% and 26.6% were single [Table 2].

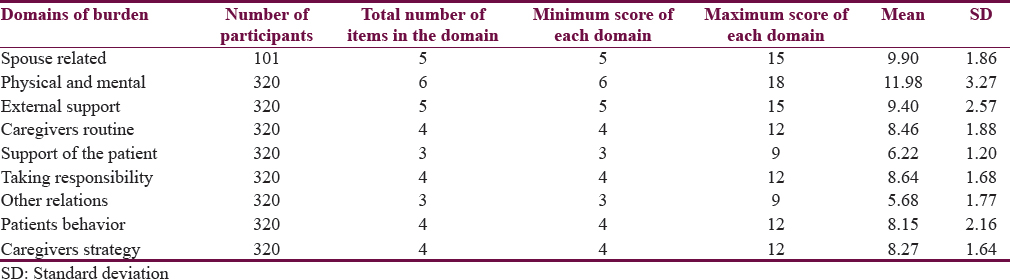

The findings from this study revealed that caregiving leading to severe burden was reported by 40.9% and moderate burden by 59.1% [Table 3].

The highest amount of burden was seen in areas of physical and mental health, spouse related, and external support. This was followed by increased burden in areas of taking responsibility, caregiver's routine, caregiver's strategy, and patient's behavior. Least amount of burden was seen in the areas of support of the patient and other relations [Table 4].

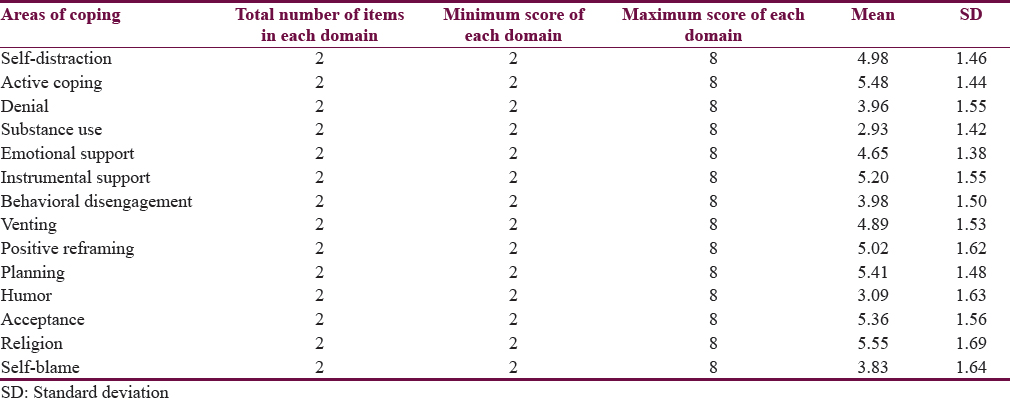

The most frequently used coping styles were religion, active coping, planning, acceptance, instrumental support, and positive reframing. This was followed by self-distraction, venting, and emotional support. The least used coping style was denial, behavioral disengagement, self-blame, humor, and substance use [Table 5].

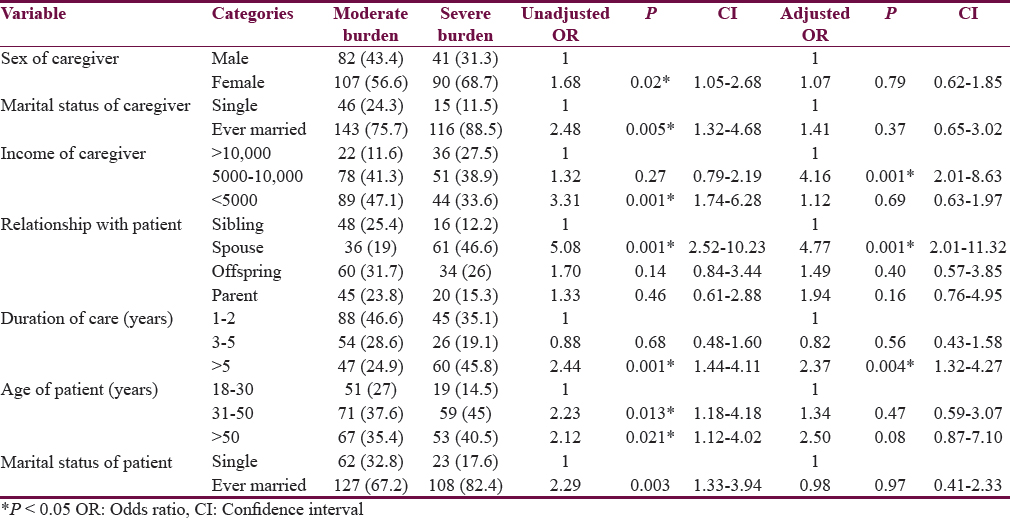

Following univariate analysis, sex of the caregiver, marital status of the caregiver (P = 0.05), income of the caregiver (P = 0.001), relationship with the patient (P = 0.001), duration of care (P = 0.001) and marital status of the patient (P = 0.003) were found to be significantly associated with caregiver burden. This was followed by multiple logistic regressions to get an adjusted OR in which low income (P = 0.001), spouse as a caregiver (P = 0.001), and duration of caregiving for more than 5-year duration (P = 0.004) were found to be significant.

The odds of severe burden among caregivers whose income was below INR 5000 was 4.16 times greater in comparison to the caregivers whose income was more than INR 10000. The odds of severe burden among caregivers who was the spouse was 4.77 times greater in comparison to those of siblings. The odds of severe burden among caregivers who provided care for more than 5 years was 2.37 times greater in comparison to the caregivers who provided care for 1–2 years [Table 6].

DISCUSSION

Caregivers, who take the major responsibility of caregiving for a mentally ill individual, have to undergo undesirable levels of severe burden.[7] The caregivers are in need of support and understanding. Furthermore, the mentally ill patient can dominate them; due to this, there may be a rise in distress and it may affect their ability to handle the crisis.[9] Negative quality of life faced by the caregivers can lead to poor quality of caregiving for those under their care as well as deterioration of their own quality of life. Inability to cope with the situation could add to the possibility of abuse of the patient leading to further deterioration of the condition.[10]

In this study, severe burden due to caregiving accounted for 40.9% and moderate burden was found among 59.1%, which is comparable to a study conducted by Mandal et al.[11] in a tertiary care general hospital in northern India among thirty caregivers of schizophrenic patients. Kaur[10] in New Saini Psychiatric Hospital, Hoshiarpur, Punjab, also reported similar findings in their study done among 100 caregivers of schizophrenic patients with moderate burden experienced by 50% of caregivers and severe burden by 49% of caregivers.

The burden assessment scale showed that highest amount of burden was seen in the areas of physical and mental health domain which assessed the caregiver burden resulting from the feelings of depression, frustration and tiredness, spouse-related domain which related to the help received from the spouse, and burden in areas of external support such as support and appreciation from family, relatives, and friends. Least amount of burden was seen in the areas of support of the patient such as the need to support the patient and other relations such as disruption of family activities and effect on other relations. These findings were similar to a study conducted by Gandhi and Thennarasu[12] in a precise tertiary care neuropsychiatric hospital at Bangalore in the year 2012 which was done on thirty caregivers of inpatients diagnosed with depression. Swapna et al.[13] in their study on the caregivers of bipolar affective disorder and alcohol dependence syndrome patients recruited from the psychiatric outpatient department (OPD) of hospitals which provided clinical services to J.J.M. Medical College also concurred that domains such as physical and mental health, caregiver's routine, and spouse related showed highest amount of burden, followed by external support, patient behavior, caregiver's strategy, taking responsibility, and support of patient. Least burden was seen in the areas of other relations.

The BCS showed that most frequently used coping styles were drawing strength from religious activities, active coping in the form of trying to do something about the situation to make it better, planning, acceptance of the situation, instrumental support as getting help and advice from others, and positive reframing practices such as seeing something good in what is happening. Least used coping styles were denial which meant refusing to believe that it has happened, behavioral disengagement such as giving up trying to deal with it, self-blame such as blaming one's own self for what is happening, humor such as making fun and jokes, and substance use meaning the use of alcohol or drugs to overcome it. Seeking spiritual support was also seen in a study conducted by Eaton et al.[14] which was done among 45 caregivers in a psychiatric unit of a hospital in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. In the Indian context, Malhotra and Thapa[15] conducted a study among 75 caregivers from the urban and rural areas. They were recruited into the study from a psychiatric OPD of Lucknow in north India. Review articles by Shah et al.[16] and Grover et al.[6] also showed that religious coping played an important role in coping.

Lower income, caregiving for a mentally ill spouse, and increasing duration of caregiving increased the odds of experiencing severe burden among caregivers. An income level below INR 5000 increased the odds of severe burden to 4.16 times as compared to those with a higher income above INR 10000.

Being a spouse increased the odds of severe burden to 4.77 times as compared to that of being a sibling

Providing care for more than 5 years increased the odds of severe burden to 2.37 times as compared to those who provided care for 1–2 years.

CONCLUSION

This study concluded that caregivers of the mentally ill individuals do undergo a lot of burden, which accounted for 40.9% of severe burden. Highest areas of burden were seen in the areas of physical and mental health, spouse related, and external support. Severe burden was more in lower socioeconomic group as compared to the higher socioeconomic group, it was more in spouse as compared to siblings, and it was more in caregivers who had been taking care of the mentally ill patient for more than 5 years as compared to those who had been taking care for 1–2 years. Frequently used coping strategies were religion, active coping, and planning.

Limitations

Caregivers who were motivated participated in the study as they were approached while waiting to seek care. Language, literacy, and stigma related to family members suffering from mental health conditions were the main barriers faced while conducting the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the respondents who participated in this study and the clinicians and staff at the private tertiary care centers, KMC and AV Baliga Hospital, and the Community Health Center at Brahmavar, for their support during the conduct of this study.

REFERENCES

- Mental health in India – Issues and concerns. 2002. J Ment Health Ageing. 8:255-60. Available from: http://www.papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1553068

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of care on caregivers of schizophrenia patients: A correlation to personality and coping. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:VC01-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian psychiatric epidemiological studies: Learning from the past. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:S95-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden among caregivers of mentally-ill patients: A rural community – Based study community medicine. Int J Res Dev Health. 2013;1:29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiver burden in severe mental illness, review article. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2011;14:211-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coping among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24:5-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden and coping of caregivers of physical and mental illnesses. 2013. Delhi Psychiatry J. 16:367-4. Available from: http://www.medind.nic.in/daa/t13/i2/daat13i2p367.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Instrument to assess burden on caregivers of chronic mentally ill. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:21-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The strengths of families in supporting mentally-ill family members. Curationis. 2015;38:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caregiving burden and social support among caregivers of schizophrenic patients. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2014;17:337-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and its correlates. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2014;17:343-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden among caregivers of clients with depression a scientific study. 2012. Int J Adv Nurs Sci Pract. 1:20-8. Available from: http://www.medical.cloud.journals.com/index.php/IJANSP/article/view/Med-18/pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden on caregivers in bipolar affective disorder and alcohol. Int J Biol Med Res. 2012;3:1992-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coping strategies of family members of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Nurs Res Pract 2011 2011:392705.

- [Google Scholar]

- Religion and coping with caregiving stress. Int J Multidiscip Curr Res. 2015;3:613-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological distress in carers of people with mental disorders. Br J Med Pract. 2010;3:a327.

- [Google Scholar]