Translate this page into:

Beyond Bounds of Reality: Acute Stress Disorder Presenting with Delusional Misidentification Syndromes

Address for correspondence: Dr. Karthick Subramanian, Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India. E-mail: karthick.jipmer@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS) is characterized by the consistent misidentification of persons, places, or events with delusional conviction.[1] DMS encompasses hypoidentification (Capgras) and hyperidentification types (Fregoli syndrome, intermetamorphosis syndrome, and syndrome of subjective doubles).[2] DMS was observed in various affective and psychotic illnesses.[23] We present the clinical scenario in which acute stress disorder manifested with a combination of Capgras (D1) and Frégoli delusions (D2). We also discuss their psychopathological evolution and their response to psychosocial interventions.

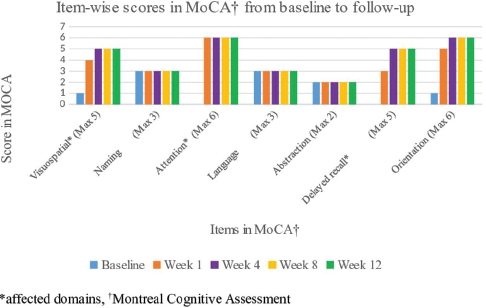

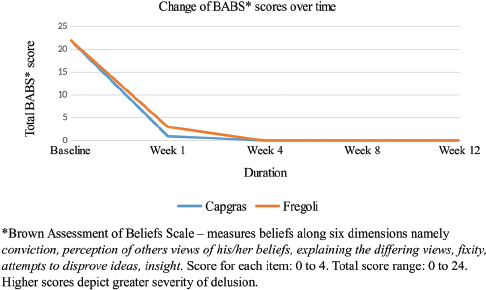

Mrs. S, with no past or family history of psychiatric illness, was enduring a long-standing marital conflict. When her husband sold their land for financial reasons, she strongly protested. Her fracas with the buyer ended in the latter suing her. The distraught husband demanded police action and threatened of divorce. Both the events catalyzed intense anxiety resulting in psychomotor agitation and disturbed sleep. Soon, she claimed that her real husband was missing and that the land buyer had taken on her husband's appearance. She vouched that the bald head and an abrasion on the leg resembled the persecutor (D1). Hours later, she perceived that her persecutor (land buyer) had camouflaged as her neighbors plotting to kill her (D2). Her beliefs were unshakeable even with family's counter-arguments. Her agitation and suicidal behaviors necessitated hospitalization. A detailed history ruled out any manic or depressive or other psychotic symptoms. She displayed deficits in visual processing, memory, and attention according to the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test [Figure 1].[4] A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 diagnosis of “Brief psychotic disorder” was entertained.[5] Her baseline blood biochemistry was unremarkable. Within 3 days of risperidone 2 mg/day and benzodiazepines, the patient became calm but harbored the delusions. Supportive counseling sessions involving the patient and her husband addressed the underlying conflicts resulting in significant reduction of anxiety. The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale[6] was used to calibrate the rate of resolution of delusions (D1 and D2) [Figure 2]. Even as the psychotropics were stopped within a week, fortnightly follow-up sessions were continued for 3 months without any relapse of symptoms. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and her husband.

- Findings from Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. Each domain-wise distribution of scores is depicted in the figure

- The figure depicts the rate of resolution of delusion as corroborated by the scores in the Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale. The blue line represents Capgras delusion and the orange line represents Fregoli delusion

The patient had an abrupt onset of illogical and incorrigible beliefs in response to acute stress. The ideas germinated independently and acquired delusional dimensions: conviction, pressure, extension, bizarreness, and deviant behavior.[7] Their psychopathological origin concords with the two-factor theory of DMS: one inducing the delusion and defining its content (imminent threat from the persecutor and her husband), the other which hinders rejecting that belief (intense anxiety and a threat to self-existence).[3] Neurobiological studies indicate a dysfunctional connectivity between the face-processing areas and temporal lobes in DMS which is reflected as visual processing and memory deficits in the patient.[8] Although the antipsychotics could have influenced the response, stress-induced short-lasting psychopathology resolving with psychosocial interventions along with a complete remission in the follow-up pointed toward a diagnosis of “acute stress reaction.”

Our report will add to the existing literature that DMS can occur in neurotic disorders among various other psychiatric disorders. Cognizance of the association between “acute stress disorders” and DMS will guide our assessment and treatment strategies. Future research should ascertain their diagnostic stability and devise appropriate treatment guidelines.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- The delusional misidentification syndromes: Strange, fascinating, and instructive. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:185-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- The Brown Assessment of Beliefs Scale: Reliability and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:102-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Approaching delusional misidentification syndromes as a disorder of the sense of uniqueness. Psychopathology. 2006;39:261-8.

- [Google Scholar]