Translate this page into:

Bedside Intracranial Hematoma Evacuation and Intraparenchymal Drain Placement for Spontaneous Intracranial Hematoma Larger than 30cc in Volume: Institutional Experience and Patient Outcomes

Address for correspondence: Dr. Tyler Carson, Department of Neurosurgery, Riverside University Health System - Medial Center 26520 Cactus Avenue, Moreno Valley, CA 92555, USA. E-mail: t.carson@RUhealth.org

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) accounts for significant morbidity and mortality in the United States. Many studies have looked at the benefits of surgical intervention for ICH. Recent results for Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue-type Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage-II trials have shown promise for a minimally invasive clot evaluation on improving perihematomal edema. Often rural or busy county medical centers may not have the resources available for immediate operative procedures that are nonemergent. In addition, ICH disproportionally affects the elderly which may not be stable for general anesthetics. This study looks at a minimally invasive bedside approach under conscious sedation for evacuation of ICH.

Materials and Methods:

Placement of the intraparenchymal hemorrhage drain utilizes bony anatomical landmarks referenced from computed tomography (CT) head to localize the entry point for the trajectory of drain placement. Using the hand twist drill intracranial access is gained the clot accessed with a brain needle. A Frazier suction tip with stylet is inserted along the tract then the stylet is removed. The clot is then aspirated, and suction is then turned off, and Frazier sucker is removed. A trauma style ventricular catheter is then passed down the tract into the center of hematoma and if no active bleeding is noted on postplacement CT and catheter is in an acceptable position then 2 mg recombinant tissue plasminogen activator are administered through the catheter and remaining clot is allowed to drain over days.

Results:

A total of 12 patients were treated from October 2014 to December 2017. The average treatment was 6.4 days. The glascow coma scale score improved on an average from 8 to 11 posttreatment with a value of P is 0.094. The average clot size was reduced by 77% with a value of P = 0.0000035. All patients experienced an improvement in expected mortality when compared to the predicted ICH score.

Discussion:

The results for our series of 12 patients show a trend toward improvement in Glasgow Coma Scale after treatment with minimally invasive intraparenchymal clot evacuation and drain placement at the bedside; although, it did not reach statistical significance. There was a reduction in clot size after treatment, which was statistically significant. In addition, the 30-day mortality actually observed in our patients was lower than that estimated using ICH score. Based on our experience, this procedure can be safely performed at the bedside and has resulted in better outcomes for these patients.

Keywords

Bedside

bedside

intracranial hemorrhage

minimally invasive

twist drill

INTRODUCTION

Nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhages (ICH) occur for a number of reasons including uncontrolled hypertension, amyloid angiopathy, anticoagulant use, cerebrovascular disease, tumors, migraines, and those that occur after invasive procedures. Bleeding is usually short-lived and is tamponaded by anatomical and physiological means, however, is associated with a 30 days morbidity and mortality of 60% and 30%, respectively.[1] Elevated blood pressure defined as systolic pressure <140 mmHg is seen in 75% of patients with acute ICH, and strict control of blood pressure is paramount in the prevention of delayed rebleeding.[2] The ICH score described by Hemphil in 2001 gives us a good predictive factor for the predicts 30 days mortality.[3]

Many attempts to classify surgical indications for evacuation of ICH have been and continue to be studied. The international surgical trial in intracerebral hematoma (STICH) looked at the outcome of 1033 patients from 83 centers in 27 countries patients treated with early surgery (open craniotomy) versus initial conservative treatment.[4] Ultimately, the STICH trial showed no significant difference between early surgical treatment and nonsurgical treatment groups as a whole. However, there was a subset of the early surgical group which seemed to have a better outcome than conservatively treated patients. These patients had supratentorial ICH that came within 1 cm of the surface. To further investigate these findings the STICH II trial was performed which looked at early surgery (within 48 h) versus initial conservative treatment specifically for patients with ICH with the volume of 10–100 ml, within 1 cm of the surface, without IVH and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) motor score of 5–6 and GCS eye-opening score of ≥2.[5] The results showed there was no increase in death or disability at 6 months between groups and there was a small benefit in overall survival.

Clearly, there is a subset of patients that benefit from evacuation of hematoma. To that end, the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue-type Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage (MISTIE) and MISTIE-II trials looked to employ a minimally invasive approach to clot evacuation in hopes to decrease the clot size and perihematomal edema (PHE) more effectively than medical treatment alone.[67] Currently, the MISTIE III trial is underway and will determine if the reduction in PHE and clot size results in improved neurologic outcome. Here at Arrowhead Regional Medical Center (ARMC), we have employed similar techniques, but adapted them to be performed bedside in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting rather than under general anesthesia in the operative room.

The goal of this study is to discuss the institutional experience and patient outcomes over the past 3 years in the placement of bedside intraparenchymal drains for intracranial hematomas larger than 30cc in size.

CASE SERIES

Beginning in October 2014 our institution began placement of intraparenchymal drains for patients with intracranial hematomas >30cc in volume and not related to aneurysmal or arteriovenous malformations rupture. With this study, a retrospective review of patient data was performed to determine the effectiveness of IPH drain placement. The primary outcome measure was improvement in GCS from presentation to posttreatment. Secondary outcome measures were reduction in clot size, actual versus predicted mortality, re-bleeding associated with catheter placement or after recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) administration and catheter misplacement requiring repositioning.

The technical placement of the IPH drain utilizes bony anatomical landmarks referenced from CT head to localize the entry point for the trajectory of drain placement. The entry point is also chosen keeping in mind where the clot comes closest to the cortical surface, preferably 2–3 cm from the Sylvain fissure, midline, or venous sinuses and avoiding eloquent brain tissue such as motor strip. Hair is clipped and sterile preparation of surgical site performed. After local anesthetic and appropriate conscience, sedation is administered a 3 cm incision carried down to the cranium. Using the hand twist drill, two holes are created in same incision ~2 cm apart one hole directed toward the center of IPH. The dura is opened at both holes. A brain needle with stylet is inserted into clot keeping in mind trajectory and depth at which clot will be encountered based on CT imaging. Once the clot has been accessed, the tract is slowly dilated by rotating the needle in a progressively wider circular motion. A Frazier suction tip with stylet is inserted along the tract then the stylet is removed. The wall suction is then connected to the Frazier tip and turned on to 90–120 mmHg suction. The clot is then aspirated until approximately 50% of clot remains based on the output from wall suction. The suction is then turned off, and Frazier sucker removed. A trauma style ventricular catheter is then passed down the tract into the center of hematoma and tunnel >5 cm from the insertion site. The drain is secured to skin and incision is closed. The catheter is connected to blub reservoir but left off suction initially. A postprocedure CT Head is obtained to ensure catheter is in the center of the hematoma cavity. If no active bleeding is noted and the catheter is in an acceptable position, then 2 mg rtPA are administered through the catheter immediately on return to ICU, and the drain is clamped for 1 h then opened to bulb suction. The CT head is repeated after 12 h and if no increase in the size of hematoma we proceed with administration of 2 mg rtPA per catheter every 12 h clamping for 1 h after each administration. It is important to maintain strict systolic blood pressure SBP goal of <130 mmHg during rtPA administration. The administration of rtPA is continued until the output from the catheter is minimal or CT head showing clot size <15 cc volume.

RESULTS

A total of 12 patients were treated from October 2014 to December 2016, [Table 1]. Informed consent was obtained from family member. All patients were treated in the ICU at ARMC through the method described above. All procedures were performed by a neurosurgery resident. Of the 12 patients, six patients had the procedure performed by a single surgeon. The remaining six were performed by various surgeons. One patient had care withdrawn per family request after the drain was placed and was withdrawn from the study.

The average number of days treated with the drain was a mean 6.4 days and median 5 days. The number of days treated varied based on the resolution of the hematoma.

The patient's level of consciousness was tracked throughout the hospital course through score GCS. The median initial GCS on arrival was 8T. The lowest GCS that received treatment was a patient who presented as a GCS 5T and the highest was a GCS 12. The median GCS after treatment was 11T. The GCS on arrival and posttreatment was compared using the student t-test and P value was calculated to be 0.094 which did not reach statistical significance.

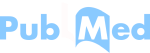

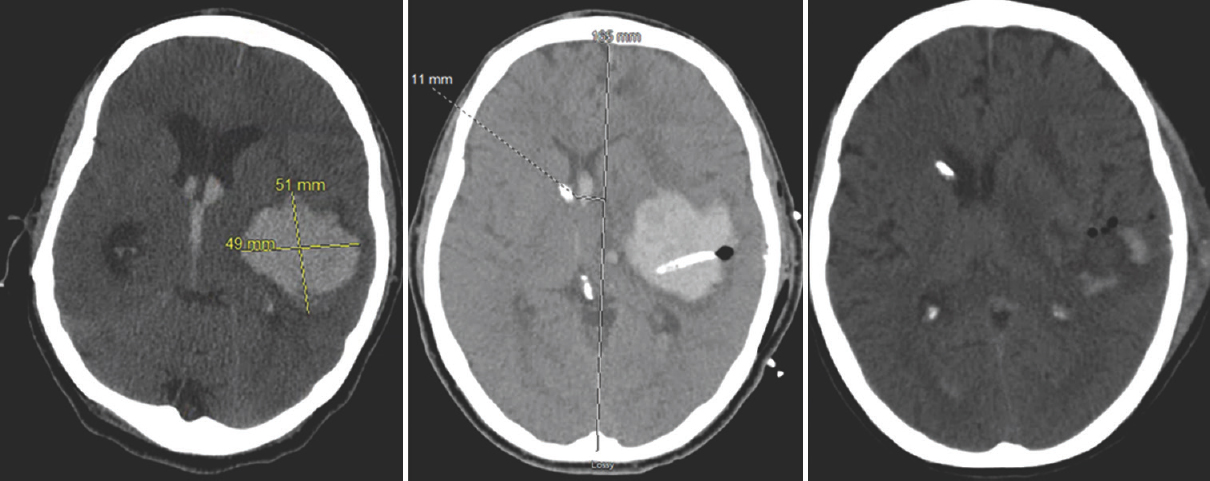

The average clot size on admission was 70.87 cc with a range of 26.25–113 cc. After treatment the average clot size was reduced to 15.95 cc, a reduction of 76.9% on an average. Figures 1 and 2 show CT head, CT head postdrain placement, and CT head posttreatment course. The student t-test was performed, and the P value was calculated to be 0.0000035 which was statistically significant.

- Computed tomography head axial cut section of patient # 6 showing from left to right presenting intracranial hemorrhage, postdrain placement, and posttreatment

- Computed tomography head axial cut section of patient #3 showing from left to right presenting intracranial hemorrhage, postdrain placement, and posttreatment

In addition, all patients showed decreased 30-day mortality when compared to predicted 30-day mortality based on ICH score on arrival. There was one incidence of rebleeding which stabilized and treatment was continued. There were two incidences of drains requiring repositioning.

CONCLUSION

The benefit of the evacuation of ICH hematomas remains a controversial subject. Some argue that evacuation is only indicated in life-threatening situations such as impending herniation due to the morbidity and mortality associated with craniotomy without evidence of significant neurologic improvement. Other studies indicated that a reduction in mass effect from the evacuation of ICH results in decreased PHE and decreased secondary injury similar to the viable penumbra in the case of ischemic stroke. Ideally, the answer to both cases is a minimally invasive surgical approach that reduces morbidity and mortality yet results in a reduction of PHE. The MISTIE trail attempts to address this with minimally invasive surgical clot evacuation. The study takes this concept a step further by performing minimally invasive clot evacuation in an ICU setting at the patient's bedside. By performing this surgery bedside, we have been able to limit our patient's exposure to general anesthesia, which in many cases results in patient remaining intubated postoperative and the sedative effects of general anesthetics.

The results for our series of 12 patients show a trend toward improvement in GCS after treatment with minimally invasive intraparenchymal clot evacuation and drain placement at the bedside; although, it did not reach statistical significance. There was a reduction in clot size after treatment, which was statistically significant. In addition, a single case of re-bleeding was noted and 2 cases of catheter placement that required repositioning. These, however, did not affect the reduction in clot size posttreatment nor result in a drop in mental status. In addition, the 30-day mortality actually observed in our patients was lower than that estimated using ICH score.

Based on our experience this procedure can be safely performed at the bedside. The use of electromagnetic emitter or other frameless stereotaxy may be beneficial in the novice surgeon performing this procedure to avoid misplacement of the catheter. This procedure was extremely effective in reducing clot size, and data trends indicated there might be a benefit to improvement in neurologic status. Ultimately, more patients need to be treated with a longer follow-up period to determine the effectiveness of this technique.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Blood pressure management in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: Current evidence and ongoing controversies. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2015;21:99-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of elevated blood pressure in 563,704 adult patients with stroke presenting to the ED in the United States. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:32-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ICH score: A simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:387-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;382:397-408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minimally invasive surgery plus recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for intracerebral hemorrhage evacuation decreases perihematomal edema. Stroke. 2013;44:627-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary findings of the minimally-invasive surgery plus rtPA for intracerebral hemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE) clinical trial. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;105:147-51.

- [Google Scholar]