Translate this page into:

Assessment of onset-to-door time in acute ischemic stroke and factors associated with delay at a tertiary care center in South India

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Anees A, Panicker P, Iype T, Sreelekha K. Assessment of onset-to-door time in acute ischemic stroke and factors associated with delay at a tertiary care center in South India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:86-94. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_325_2023

Abstract

Objectives:

Intravenous thrombolysis is an effective treatment of acute ischemic stroke but has a narrow therapeutic time window of 3–4.5 h. Pre-hospital delay is a major barrier to patients becoming eligible for thrombolysis. This single-center study assessed the factors causing longer onset-to-door (OTD) time to identify measures that will help decrease the delay.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with acute ischemic stroke presenting to the emergency department from August to October 2022 were included in the study. The data were collected using a structured questionnaire and was completed by interviewing the patient or the caregivers. Patients were classified as early and late arrivers with the cutoff being 3.5 h. We then analyzed the relationship between early arrival and demographic factors, clinical factors, patient response factors, and logistic factors.

Results:

Our study consisted of 153 patients. The average OTD time was 674.33 ± 812.713 min (median: 300; interquartile range: 151–885). The pre-hospital delay was present in 66% of patients. 16.9% of patients came beyond 24 h. In the multivariate analysis, the odds of early arrival were higher among patients who perceived their symptoms as serious (odds ratio [OR]: 18.801; confidence interval [CI]: 3.728–94.803) and lower among patients who experienced a delay in reaching due to traffic (OR: 0.085; CI: 0.008–0.873). Lack of knowledge about stroke centers among both patients and health professionals also contributed to longer OTD times. Out of 52 early arrivers, 24 received thrombolytic therapy after excluding wake-up strokes and contraindications.

Conclusion:

Pre-hospital delay continues to stand in the way of patients receiving thrombolysis. Comprehensive stroke education, increasing awareness regarding stroke centers, and promoting ambulance services are some of the interventions which could help tackle the issue.

Keywords

Onset-to-door time

Pre-hospital delay

Ischemic stroke

INTRODUCTION

In 2019, stroke was the second leading cause of death (11.6% of total deaths) and the third leading cause of the disability-adjusted life years (5.7% of total DALYs) globally.[1] The number of incident stroke cases in India in 2019 was 1.29 million, and the number of deaths was 699000. It was the largest contributor to the total neurological disorder DALYs (37.9%).[2]

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) trial showed that patients who received alteplase were 30% more likely to have better outcomes at 3 months on assessment scales (global odds ratio for a favorable outcome was 1.7; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2–1.6).[3] The Third International Stroke Trial-3 demonstrated that treatment with intravenous tPA within 1.5 h of last-seen-well was associated with a favorable outcome at 3 months compared with placebo with an odds ratio of 2.81 (95% CI, 1.75–4.50).[4] Most studies in the published literature have focused on factors affecting door-to-needle time and on devising strategies to decrease it. However, patients with acute ischemic stroke do not even reach the hospital within the window period and, hence, miss the opportunity of becoming eligible for thrombolysis. Hence, the time taken from symptom onset to arrival at the hospital is an important area for intervention.

Hence, we initiated this single-center study to assess the time taken from the onset of symptoms to arrival at the emergency department and look into the factors causing the pre-hospital delay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and period

This cross-sectional study was carried out from August 05, 2022, to October 05, 2022. Data collection was done prospectively. The data were collected specifically for this study.

Setting

This study was conducted in the department of medicine and the department of neurology of a tertiary care hospital in Kerala.

Selection criteria

All consecutive patients presenting with symptoms of acute ischemic stroke in the emergency department, irrespective of treatment received, were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Stroke mimics, hemorrhagic and venous infarcts, and those unwilling to provide consent were excluded

Data collection

Data from a tertiary care center located in Kerala were collected.

The hospital offers round-the-clock thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke.

Data from consecutive stroke patients were prospectively collected using a structured questionnaire. The patient or caregiver was interviewed in the local language Malayalam.

The questionnaire had questions addressing demographic details, including age and sex. Information about the time of onset of symptoms, day of onset, presenting symptoms, and risk factors with details regarding the mode of transport used by the patient to the hospital was collected. Whether they visited a local hospital before coming to our center was noted. The presence of previous stroke history and family history of stroke were inquired into. Distance from the hospital was categorized into those staying within 40 km or those staying beyond considering it takes about an hour to cover 40 km on Indian roads. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was used to document stroke severity. The circulation of the brain, anterior or posterior which was predominantly affected, was noted. Knowledge about stroke, thrombolysis, and stroke helpline number (a dedicated pre-notification number for stroke) was assessed. Whether patients took their symptoms seriously or not was also asked for and recorded. The time of arrival at the hospital was obtained from the casualty out-patient ticket, and the onset-to-door (OTD) time was calculated.

Patients coming within 3.5 h were classified as early arrivers, and the rest as late arrivers considering the NINDS recommended door-to-needle time of 60 min.[5]

Statistical analysis

The entire statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 29.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for MS Windows. The association between the quantitative and qualitative variables was assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test where appropriate. The association between two quantitative variables was assessed using the Chi-square test. Binary logistic regression was done to model the independent predictors of pre-hospital delay. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study. Privacy and confidentiality of data were maintained.

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

The study consisted of 153 participants who presented with acute ischemic stroke to the emergency department of the tertiary care hospital; of which 90 were male (58.8%) and 63 were female (41.2%). The mean age was 62.88 ± 13.59 years (median-64 years).

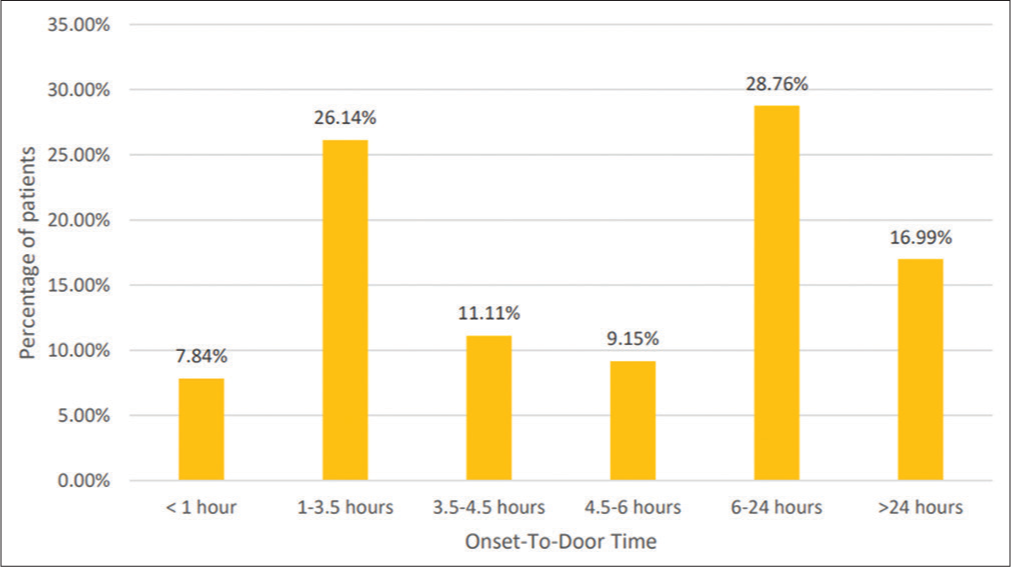

Demographic and clinical profile of patients

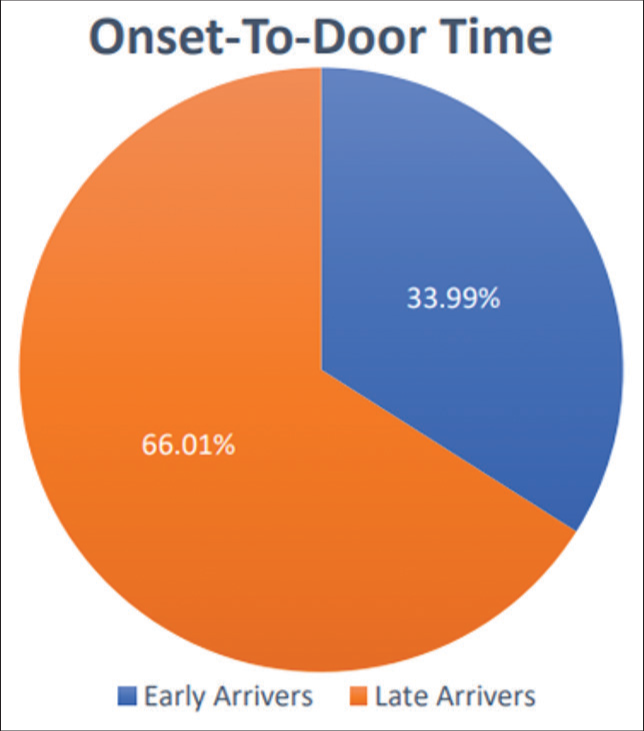

Demographic and clinical data of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The mean OTD time was 674.33 ± 812.713 min (median: 300; interquartile range: 151–885). Out of 153, 101 (66.0%) patients were late arrivers and came after 3.5 h [Figure 1]. 15.7% of patients received thrombolysis. Other salient data is represented pictorially in Figures 2-9.

| Age | 62.88±13.59a |

|---|---|

| ≤45 years | 17 (11.1)b |

| >45 years | 136 (88.9)b |

| Gender | |

| Male | 90 (58.8)b |

| Female | 63 (41.2)b |

| Distance from onset to hospital | 34.84±25.8a |

| ≤40 km | 100 (65.4)b |

| >40 km | 53 (34.6)b |

| NIHSS | |

| ≤15 | 110 (71.9)b |

| >15 | 43 (28.1)b |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 143 (93.5)b |

| Single | 10 (6.5)b |

| Financial status | |

| High SES | 26 (17.0)b |

| Middle SES | 17 (11.1)b |

| Low SES | 110 (71.9)b |

| Place of stroke onset | |

| Home | 129 (84.3)b |

| Office/Workplace | 10 (6.5)b |

| Road | 9 (5.9)b |

| Out-patient setting | 4 (2.6)b |

| Chronic health-care facility | 1 (0.7)b |

| Education | |

| ≤12th grade | 142 (92.8)b |

| >12th grade | 11 (7.2)b |

| Mode of living | |

| Alone | 14 (9.2)b |

| Family | 137 (89.5)b |

| Friends | 2 (1.3)b |

| Place of residence | |

| Rural | 86 (56.2)b |

| Urban | 67 (43.8) |

| Visit to a local hospital | |

| Yes | 127 (83.0)b |

| No | 26 (17.0)b |

| Time of onset | |

| Day | 119 (77.8)b |

| Night | 34 (22.2)b |

| Day of onset | |

| Weekday | 143 (95.4)b |

| Weekend | 10 (6.5)b |

| Onset-to-door time | 674.33±812.713a |

| Early arrivers | 52 (34.0)b |

| Late arrivers | 101 (66.0)b |

| Previous history of stroke | |

| Present | 28 (18.3)b |

| Absent | 125 (81.7)b |

| Family history of stroke | |

| Present | 25 (16.3)b |

| Absent | 128 (83.7)b |

| Stroke territory | |

| Anterior | 132 (86.3)b |

| Posterior | 21 (13.7)b |

| Bystander at onset | |

| Family member | 105 (68.6)b |

| Friend | 8 (5.2)b |

| Colleague | 6 (3.9)b |

| Stranger | 6 (3.9)b |

| Alone | 25 (16.4)b |

| Health professional | 2 (2.0)b |

| Recognition of stroke | |

| Yes | 39 (25.5)b |

| No | 114 (74.5)b |

| Perceived symptoms as serious | |

| Yes | 109 (71.2)b |

| No | 44 (28.8)b |

| Knowledge about thrombolysis | |

| Yes | 6 (3.9)b |

| No | 147 (96.1)b |

| Mode of transport | |

| Ambulance | 101 (66.0)b |

| Auto | 26 (17.0)b |

| Own | 24 (15.7)b |

| Vehicle taxi | 2 (1.3)b |

- Proportion of patients arriving within 3.5 h.

- Symptoms of patients.

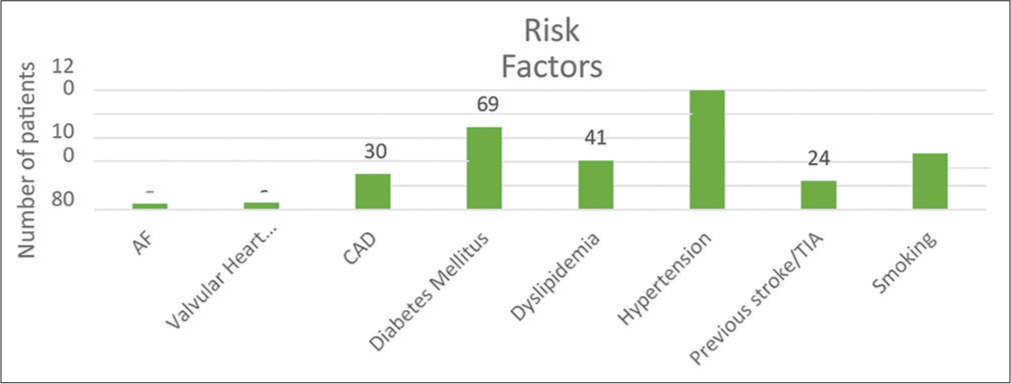

- Risk factors for acute ischemic stroke in patients. AF: Atrial fibrillation, CAD: Coronary artery disease, TIA: Transient ischemic attack

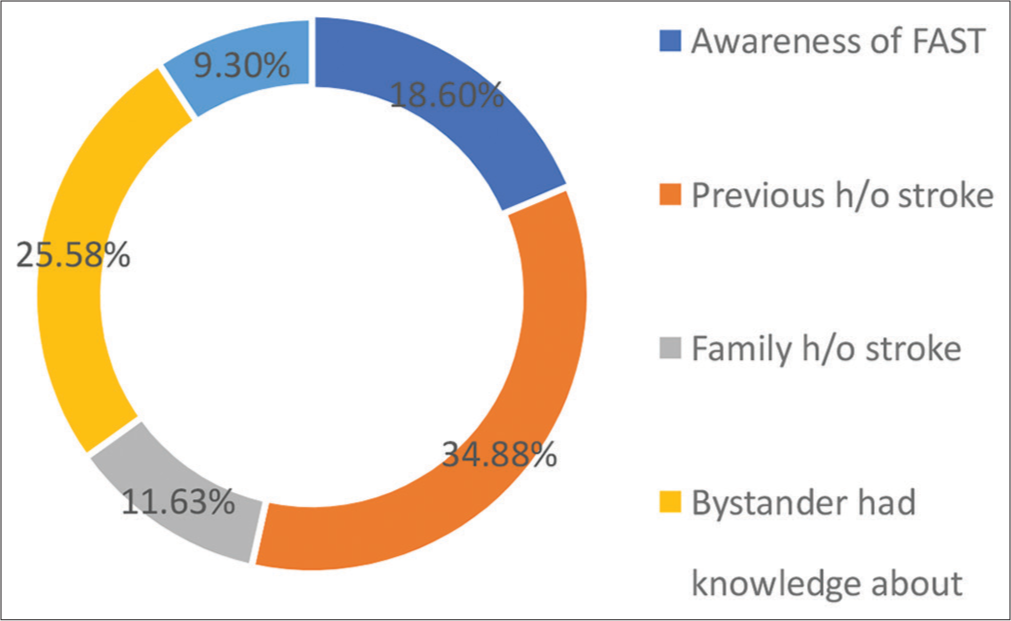

- Sources of stroke knowledge.

- Proportion of patients who recognized stroke.

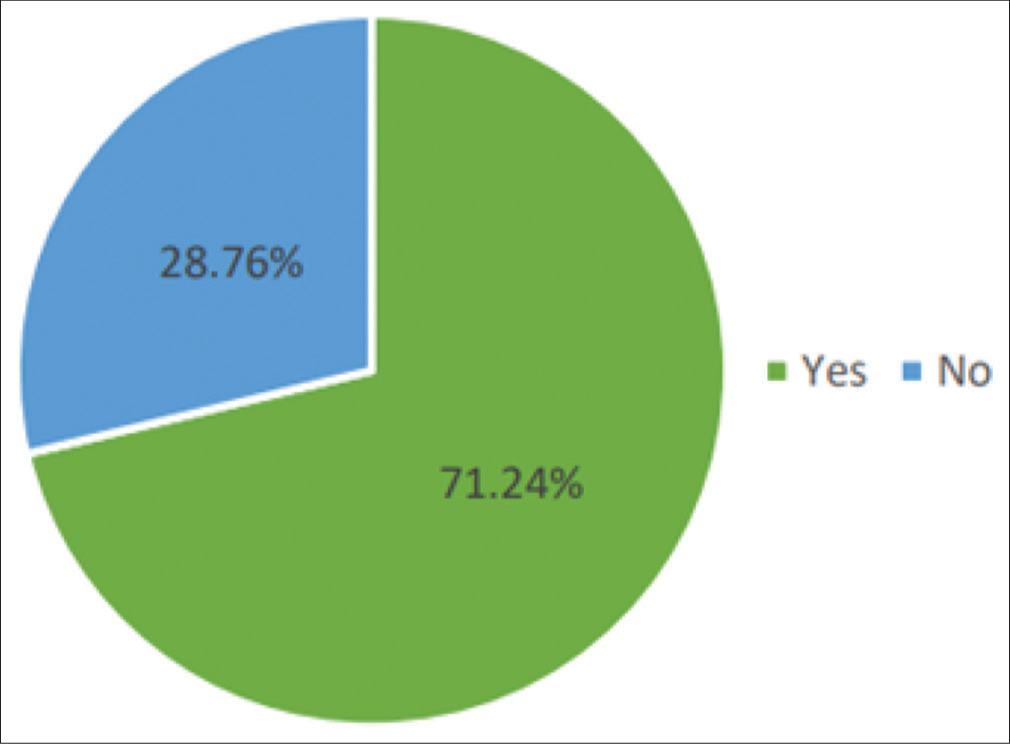

- Proportion of patients who perceived symptoms as serious.

- Mode of transport.

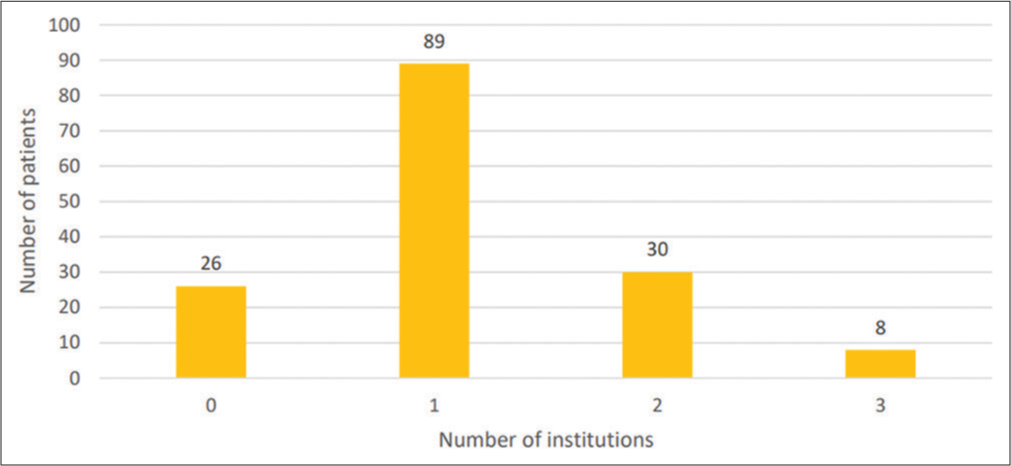

- Number of institutions visited.

- Division of onset-to-door time.

Univariate analysis

Demographic, clinical variables, patient factors, and logistic factors were compared between the group of early arrivers and late arrivers. These data are summarized in Table 2.

| Variable | Early arrivers (n=52) | Late arrivers (n=101) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.904 | ||

| ≤45 years | 6 | 11 | |

| >45 years | 46 | 90 | |

| Gender | 36 | 54 | 0.061 |

| Male | |||

| Female | 16 | 47 | |

| Distance from onset to hospital | 0.012 | ||

| ≤40 km | 41 | 59 | |

| >40 km | 11 | 42 | |

| Marital status | 0.309 | ||

| Married | 47 | 96 | |

| Single | 5 | 5 | |

| Financial status | 0.988 | ||

| High SES | 9 | 17 | |

| Middle SES | 6 | 11 | |

| Low SES | 37 | 73 | |

| Education | 0.511 | ||

| ≤12th grade | 47 | 95 | |

| >12th grade | 5 | 6 | |

| Mode of living | 0.068 | ||

| Alone | 3 | 11 | |

| Family | 47 | 90 | |

| Friends | 2 | 0 | |

| Place of residence | 0.032 | ||

| Rural | 23 | 63 | |

| Urban | 29 | 38 | |

| Place of stroke onset | 0.048 | ||

| Home | 38 | 91 | |

| Office/Workplace | 7 | 3 | |

| Road | 4 | 5 | |

| Out-patient setting | 2 | 2 | |

| Chronic health-care facility | 1 | 0 | |

| Time of onset | 0.855 | ||

| Day | 40 | 79 | |

| Night | 12 | 22 | |

| Day of onset | 0.496 | ||

| Weekday | 50 | 9 | |

| Weekend | 2 | 38 | |

| Bystander at onset | 0.038 | ||

| Family member | 33 | 72 | |

| Friend | 4 | 4 | |

| Colleague | 5 | 1 | |

| Stranger | 3 | 3 | |

| Alone | 5 | 20 | |

| Health professional | 2 | 1 | |

| Bystander’s response | <0.001 | ||

| Serious | 47 | 57 | |

| Dismissive | 0 | 24 | |

| Stroke territory | 0.120 | ||

| Anterior | 48 | 84 | |

| Posterior | 4 | 17 | |

| Previous history of stroke | 0.267 | ||

| Present | 7 | 21 | |

| Absent | 45 | 80 | |

| Family history of stroke | 0.816 | ||

| Present | 9 | 16 | |

| Absent | 43 | 86 | |

| Visit to a local hospital | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 33 | 94 | |

| No | 19 | 7 | |

| Stroke diagnosed at a local hospital | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 33 | 69 | |

| No | 0 | 25 | |

| Number of institutions visited | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 19 | 7 | |

| 1 | 32 | 57 | |

| 2 | 1 | 29 | |

| 3 | 0 | 8 | |

| Recognition of stroke | 0.770 | ||

| Yes | 14 | 25 | |

| No | 38 | 76 | |

| Perceived symptoms as serious | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 49 | 60 | |

| No | 3 | 41 | |

| Knowledge about thrombolysis | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 2 | 4 | |

| No | 50 | 97 | |

| Mode of transport | 0.064 | ||

| Ambulance | 41 | 60 | |

| Auto | 5 | 21 | |

| Own vehicle | 6 | 18 | |

| Taxi | 0 | 2 | |

| Delay in getting the ambulance | 0.039 | ||

| Yes | 0 | 7 | |

| No | 41 | 53 | |

| Delay due to traffic | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 1 | 15 | |

| No | 51 | 86 | |

| Presenting symptoms | |||

| Hemiparesis | 44 | 73 | 0.088 |

| Facial deviation | 27 | 49 | 0.690 |

| Speech disturbances | 30 | 71 | 0.119 |

| Loss of consciousness | 12 | 13 | 0.106 |

| Vertigo | 6 | 17 | 0.386 |

| Headache | 7 | 20 | 0.330 |

| Gait disturbances | 5 | 17 | 0.228 |

| Seizures | 3 | 5 | 0.829 |

| Vomiting | 7 | 17 | 0.587 |

| Blurring of vision | 2 | 6 | 0.717 |

| Risk factors | |||

| AF | 1 | 4 | 0.662 |

| Valvular heart disease | 1 | 5 | 0.664 |

| Hypertension | 34 | 66 | 0.996 |

| CAD | 15 | 15 | 0.039 |

| Dyslipidemia | 17 | 24 | 0.237 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 | 46 | 0.877 |

| Smoking | 10 | 37 | 0.027 |

| NIHSS | 0.005 | ||

| ≤15 | 30 | 80 | |

| >15 | 22 | 21 |

SES: Socioeconomic status, AF: Atrial fibrillation, CAD: Coronary artery disease, NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Multivariate analysis

Binary logistic regression was done to model the determinants of an early arrival (OTD time <3.5 h). The results of the multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 3.

| Predictor variables | β estimate | Standard error | P-value | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval for EXP (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset to hospital distance | 1.033 | 0.615 | 0.093 | 2.810 | (0.841, 9.388) |

| NIHSS score | −0.457 | 0.627 | 0.466 | 0.633 | (0.185, 2.163) |

| Place of residence | −0.019 | 0.560 | 0.973 | 0.981 | (0.328, 2.938) |

| Place of stroke onset | 1.489 | 1.309 | 0.255 | 4.434 | (0.341, 57.718) |

| Bystander at onset | −2.558 | 2.619 | 0.329 | 0.077 | (0.000, 13.129) |

| Perception of symptoms as serious | 2.934 | 0.825 | <0.001 | 18.801 | (3.728, 94.803) |

| Delay in reaching due to traffic | −2.470 | 1.191 | 0.038 | 0.085 | (0.008, 0.873) |

| CAD | −0.818 | 0.670 | 0.222 | 0.441 | (0.119, 1.639) |

| Smoking | 1.073 | 0.685 | 0.117 | 2.925 | (0.765, 11.192) |

CAD: Coronary artery disease, NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

DISCUSSION

Our study population had a median OTD time of 5 h. There seems to be an improvement in pre-hospital delay compared to the 2012 study conducted in Calicut, Kerala, where the median OTD time was 12 h.[6] The shorter delay may have been made possible by increased availability and use of ambulance services. 66% of our patients used emergency medical services (EMS) compared to 29% in the previous study. The OTD time of 5 h is also lesser than that recorded in the study conducted in Coimbatore in the neighboring state of Tamil Nadu with a median delay of 9.5 h.[7] However, 66% of the patients still arrived after 3.5 h. Among this, 17% of patients presented to the emergency department after 24 h. This is high compared to Western countries where 50–70% of patients arrive within 3 h, and the median OTD time is 1–2.5 h.[8-11]

The most significant factors associated with pre-hospital delay in the multivariate analysis were the perception of symptoms as serious and delay in reaching due to traffic.

Failure to recognize stroke was associated with delay in many previous studies.[8,12] We found that 25.5% of patients recognized stroke, which is low compared to 70–75% in developed countries and another study in North Kerala.[7] Only 8 had knowledge about the warning symptoms of a stroke.

However, 71.2% of the study participants felt that their symptoms were serious, and this was a significant factor in early arrival.

A higher NIHSS score was seen to be associated with early arrival. This is due to an increased sense of urgency as evidenced by the fact that 80% of patients with the NIHSS scores >15 felt their symptoms were serious.

Only 3.9% of patients had knowledge about thrombolysis, which is lower than 18% in the Coimbatore study and Western countries.[8-11] None of the participants knew about the stroke helpline number, even among those who have had a stroke before, and this points to an underwhelming effort at stroke education. A study from Iran showed that the median OTD time was 2 h when the stroke helpline number was called.[13] Prenotification to the stroke team in the hospital was also associated with reduced in-hospital delay in previous studies.[12,14,15] A 11% decrease in door-to-needle time was documented when prenotification was implemented.[15]

A major cause of late arrival in the univariate analysis was a visit to a local hospital. This was documented in many previous studies as well.[7,8] Only 17% of general practitioners are aware of the window period of thrombolysis according to a study from Tamil Nadu.[15] There is also a lack of knowledge about stroke-ready hospitals among both patients and doctors. 5.2% of patients visited 3 institutions. This highlights the importance of increasing awareness about stroke centers in the state.

Stroke was not diagnosed in 19.7% of patients visiting a local hospital. This points to a need to increase awareness about the symptoms of stroke, especially posterior circulation stroke.

Those living in rural areas were found to arrive late in our study. This was seen in other studies as well.[7] Patients from rural areas were seen to have lesser urgency about their symptoms compared to urban areas. 60.6% of patients who visited a local hospital also belonged to rural areas. This signifies a need to pay special attention to rural areas with respect to stroke education. The presence of risk factors did not seem to decrease pre-hospital delay, which signifies a need to educate this high-risk population.

However, we found that neither previous history of stroke nor a family history led to early arrival, which was also seen in the other studies.[16] This suggests a disconnection between knowledge and action. Zock et al. found that recognition of stroke was not followed immediately by help-seeking behaviors. Personal experiences of spontaneous improvement were one reason for the wait-and-see strategy. This study also showed that most participants were not interested in stroke education unless they had a stroke themselves.[17] Another study also found that 59% of patients waited for symptoms to resolve spontaneously.[18]

Ambulance services were utilized by 66% of the population, which is greater than that reported in the 2012 Calicut study and is comparable to Western countries with a utilization rate of 60–70%.[6,7,9-11]

The use of EMSs has been well-documented to increase the odds of early arrival in previous studies.[9-11] Although we observed a decreased OTD time in patients using ambulance services compared to those using auto, it did not produce a significant difference in arrival within 3.5 h. This is probably because most patients coming by auto live nearer to the hospital, and those living far away, use auto to visit a local hospital before finally reaching by ambulance.

However, decreased OTD time in patients using ambulance services (median 4 h) is significant since previous studies have shown that there are improved functional outcomes with early arrival irrespective of reperfusion therapy.[19] Delay in reaching due to traffic was also significantly associated with using auto as the mode of transport.

A previous study had observed that older age and female sex were associated with a shorter OTD; however, we found no correlation.[7] The presence of hemiparesis also led to shorter OTD due to the increased sense of urgency. Patients with coronary artery disease were found to arrive early, which seems to be due to the increased awareness about cardiac disease in this group.

Unlike in Western countries where living alone was an important factor leading to pre-hospital delay, the mode of living did not seem to influence OTD in our study.[11] However, being alone at the onset was found to be associated with decreased urgency and late arrival.

Stroke onset at one’s office or workplace was found to be associated with early arrival. This is probably due to the presence of one’s colleague as the bystander. Family members were seen to be more dismissive of patients’ symptoms. However, in a study conducted in Nepal, onset at home was found to lead to early arrival.[20]

In our study, education more than 12th grade was associated with greater recognition of stroke; however, this did not equate to early arrival.

Similar causes for pre-hospital delay were found in other studies conducted in India.[6,7] This calls for a comprehensive stroke education campaign to improve patients’ opportunities to avail of definitive treatment, including thrombolytic therapy and mechanical thrombectomy.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights that onset to door time delay continues to be a major hindrance to ischemic stroke patients receiving thrombolysis. Awareness campaigns focusing on thrombolysis and stroke centers among general public and primary care physicians along with improvement in ambulance services are essential to address this lacuna in stroke care in India.

Limitations

The short duration and relatively small sample size are limitations of our study.

Ethical approval

Clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using the AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

The project was done as part of ICMR’s short-term studentship program.

References

- Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:795-820.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The burden of neurological disorders across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e1129-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2009;333:1581-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The benefits and harms of intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator within 6 h of acute ischaemic stroke (the third international stroke trial [IST-3]): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:2352-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46-110.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors delaying hospital arrival of patients with acute stroke. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2015;18:162-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroke education focusing on recognition and response to decrease pre-hospital delay in India: Need of the hour to save hours. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2021;26:101309.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with delayed presentation at the emergency department in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Brain Inj. 2019;33:1257-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Time to hospital admission and start of treatment in patients with ischemic stroke in Northern Italy and predictors of delay. Eur Neurol. 2013;70:349-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors related to decision delay in acute stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:534-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of pre-hospital transport time of stroke patients to thrombolytic treatment. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2014;22:65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting pre-hospital and in-hospital delays in treatment of ischemic stroke; a prospective cohort study. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2021;9:e52.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of “stroke code”-rapid response team: An attempt to improve intravenous thrombolysis rate and to shorten door-to-needle time in acute ischemic stroke. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22:243-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving door-to-needle times for acute ischemic stroke: Effect of rapid patient registration, moving directly to computed tomography, and giving alteplase at the computed tomography scanner. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003242.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of acute ischemic stroke: Awareness among general practitioners. Neurol India. 2010;58:441-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of barriers to delivery of thrombolysis for acute stroke. Age Ageing. 2004;33:116-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic factors influencing help-seeking behaviour in an acute stroke situation. Acta Neurol Belg. 2016;116:295-301.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with pre-hospital delay and intravenous thrombolysis in China. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29:104897.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors delaying hospital admission in acute stroke: The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Neurology. 1996;47:383-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Status of prehospital delay and intravenous thrombolysis in the management of acute ischemic stroke in Nepal. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:155.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]