Translate this page into:

Acute hemichorea-hemiballism as a sole manifestation of acute thalamic infarct: An unusual occurrence

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rohan R. Mahale, Department of Neurology, MS Ramaiah Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru - 560 054, Karnataka, India. E-mail: rohanmahale83@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Abnormal involuntary movements following stroke are relatively common. They can be hyperkinetic as hemichorea (HC) and hemiballism (HB) or can be hypokinetic as Parkinsonism. Poststroke hyperkinetic movement disorders have an incidence of 0.08%.[1] They have been associated with both infarct and cerebral hemorrhage. HC is a unilateral continuous, random, and distally predominant jerking movement that may involve proximal muscles.[1] HB is a unilateral, involuntary, and large amplitude proximal movement.[2] HC-HB is an unusual manifestation in thalamic lacunar infarction as compared to more common manifestations such as pure sensory stroke, ataxic hemiparesis, painful ataxic hemiparesis, and hypesthetic ataxic hemiparesis.[3] We report a patient who presented with sudden onset, HC-HB of right limbs and was found to have acute left thalamic infarct.

A 54-year-old man presented with history of sudden onset involuntary movements in the right arm and leg for 1-day duration. The movements were random, irregular, continuous, becoming more prominent on action than rest, violent. There was no history of similar movement in the left limbs. The patient was known hypertensive for 3 years on medications with no other comorbidities. Family history was not significant. On clinical evaluation, vitals were normal, and he was conscious and oriented. Speech was normal. Motor examination revealed hypotonia of right limbs and hyporeflexia of right limbs. Sensory examination was normal. There was irregular, coarse, continuous, nonsuppressible, violent involuntary movements becoming more prominent on action than rest involving right limbs which were suggestive of right HC-HB [Video 1].

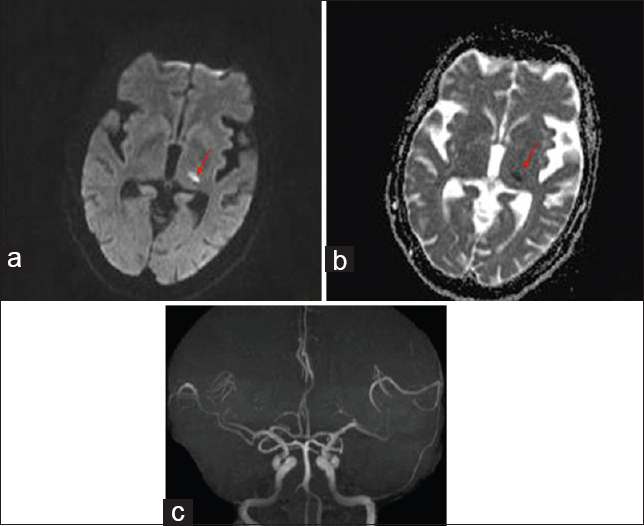

Right plantar was extensor in response. Gait was unsteady due to severe choreoballism. In view of sudden onset of symptoms, unilaterality, and presence of vascular risk factors, cerebrovascular event was considered. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed hyperintensity with restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging in left thalamus suggestive of infarct [Figure 1]. Magnetic resonance angiography of extra- and intra-cranial arteries did not reveal any significant abnormality. His complete hemogram, renal, liver, and thyroid function tests were normal. Fasting and postprandial blood glucose were normal. Carotid and vertebral artery Doppler and two-dimensional echocardiography were normal. Serological testing for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B surface antigen, and venereal disease research laboratory was negative. Serum antinuclear antibodies were negative. He was started on aspirin (150 mg daily), atorvastatin (20 mg daily), and carbamazepine (400 mg daily). There was improvement in his involuntary movements and was ambulant at 1-month follow-up [Video 2].

- Brain magnetic resonance imaging diffusion-weighted imaging image (a) showing infarct in left lateral thalamus (red arrow); apparent diffusion coefficient image (b) showing corresponding dark signal in left lateral thalamus (red arrow); magnetic resonance angiography (c) is normal

HC is the most common movement disorder following stroke. Vascular HC is typically associated with ischemic or hemorrhagic lesions of the basal ganglia. The incidence of HC-HB in acute stroke ranges between 0.4% and 0.54%, with a prevalence of 1%.[4] A study from a tertiary referral center revealed that cerebrovascular disease was the most common cause of nongenetic chorea.[5] Lesions of the contralateral striatum are more commonly associated with HC-HB apart from the subthalamic nucleus (STN).[6] In a retrospective study by Pareés et al., on poststroke HC, the most frequent site was in the lentiform nucleus, followed by cortical, thalamic, and subthalamic regions.[7] Vascular territories implicated in HC-HB include lateral lenticulostriate branches of middle cerebral artery; thalamoperforators, thalamogeniculate, and choroidal arteries of posterior cerebral artery; and recurrent artery of Huebner of anterior cerebral artery.[1] Lacunar infarcts constitute about two-third of patients with poststroke hyperkinetic movement disorders; whereas large vessel disease, cardioembolism, and hemorrhage constitute the remainder.[1]

Typically, the lesions causing HC-HB occur in the corpus striatum and STN. Thalamic lacunar infarction usually presents as pure sensory stroke, ataxic hemiparesis, and hypesthetic ataxic hemiparesis. HC-HB is the rarest neurological symptom of thalamic infarction. D'Olhaberriague et al. in their study on the 22 patients with movement disorders in ischemic stroke reported 2 patients with HC-HB secondary to thalamic lacunar infarction.[8] Takahashi et al. reported an elderly man with pure HC due to acute lacunar thalamic infarct. Our patient also had pure HC-HB in association with acute thalamic infarct.[9]

The pathophysiological mechanism of HC-HB that is described due to lesion of striatum and STN is as follow: Lesions of the contralateral striatum interrupt inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid pathways to the globus pallidus externa (GPe) resulting in increased GPe neuronal activity. The increased inhibitory GPe neuronal activity causes greater inhibition of neurons within the STN. Increased inhibition of the STN leads to a loss of excitatory control over the globus pallidus interna (GPi) causing disinhibition of the motor thalamus. The deficient GPi inhibitory input to the motor component of the thalamus results in excessive thalamocortical motor movement causing hyperkinetic movements.[6]

The pathophysiological mechanism of HC-HB described in the thalamic lesion is the disruption of the various thalamic connecting fibers from the STN, globus pallidus, posterior limb of internal capsule, and cerebellum, leading to the crucial derangement in the basal ganglia–cortical circuit.[9] Takahashi et al. did single-photon emission computed tomography study on their patient and found contralateral thalamic hypoperfusion and striatal hyperperfusion. Striatal hyperperfusion suggested increase in the striatal neuronal inhibitory activity on GPi, thus, causing disinhibition of the thalamic neurons.[9]

There are very few reports of the occurrence of HC-HB following thalamic lacunar infarction. The present case reports the relatively rare occurrence of HC-HB following thalamic lacunar infarction. The pathophysiology of chorea and location of the lesion producing it are not fully understood. Understanding the pathophysiological mechanism responsible for the HC-HB following thalamic infarction needs further research.

Videos Available on www.ruralneuropractice.com

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hemiballism-hemichorea. Clinical and pharmacologic findings in 21 patients. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:862-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudochoreoathetosis in four patients with hypesthetic ataxic hemiparesis in a thalamic lesion. J Neurol. 1999;246:1075-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperkinetic movement disorders during and after acute stroke: The Lausanne Stroke Registry. J Neurol Sci. 1997;146:109-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cause and course in a series of patients with sporadic chorea. J Neurol. 2003;250:429-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemichorea after stroke: Clinical-radiological correlation. J Neurol. 2004;251:725-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-stroke hemichorea: Observation-based study of 15 cases. Rev Neurol. 2010;51:460-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Movement disorders in ischemic stroke: Clinical study of 22 patients. Eur J Neurol. 1995;2:553-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pure hemi-chorea resulting from an acute phase of contralateral thalamic lacunar infarction: A case report. Case Rep Neurol. 2012;4:194-201.

- [Google Scholar]