Translate this page into:

A Family Study of Consanguinity in Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Barwani, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ram Lakhan, Department of Health and Human Performance, Berea College, Berea, Kentucky, USA. E-mail: ramlakhan15@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Intellectual disability (ID) can be inherited in families through consanguineous marriage. The ID in an individual can be associated with the ID, epilepsy, and mental illness in their parents. Such connections can be seen more closely among consanguineous marriages in tribal and nontribal population in India.

Objective:

This study shows a few common patterns of the consanguineous relationship in the parents of children with ID in India.

Materials and Methods:

This is a case series research design. Extreme or deviant case sampling was applied. Data were collected in homes, camps, and clinical settings in the Barwani district of Madhya Pradesh, India. The patterns of consanguineous marriages and the relationship between children with ID and their relatives with ID, epilepsy, and mental illness were analyzed and reported with pedigree charts.

Results:

Multiple patterns of consanguineous marriages in tribal and nontribal populations were observed. ID was found to be associated in children with their relatives of the first, second, and third generations.

Conclusion:

ID may inherit in individuals from their relatives of the first, second, and third generations who have ID, epilepsy, or mental illness and married in the relationship. Appropriate knowledge, guidance, and counseling may be provided to potential couples before planning a consanguineous marriage.

Keywords

Consanguinity

family history

intellectual disability

INTRODUCTION

Several determinants have been identified for intellectual disabilities (IDs). The relationship between sociodemographic, biological, environmental, and genetic factors of ID has also been explored in scientific literature. Genetic disorders such as Down syndrome, fragile X chromosome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, Cri du Chat syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, XYY, and Prader–Willi syndrome are commonly associated with IDs which may occur due to error in genetic transformation/mapping or mutation.[1234]

ID displays multidimensional arrays with genetic and medical conditions. About 25%–50% causes of ID are attributed to genetic factors.[5] Children closely match with their parents in the genetic, psychological, and physical makeup because they inherit these traits from their parents. Like good characteristics, a defective genetic material also gets inherited through the generation and potentially carries several diseases such as diabetes mellitus, heart diseases, and neurological disorders. The defective or disease-related trait transfers from relatives into their children through consanguineous relationship between the parents. Researchers have found consanguinity to be associated with a high risk for mortality among Muslim children in India and Pakistan.[67] The negative impact of consanguinity has been explored in several studies. Many evidences in literature demonstrate the negative impact of consanguinity. Parents who have ID or parents who married consanguineously with an ID relative can pass on ID in their children.[8] Approximately 90 gene defects have been identified for X-linked ID.[910] However, the translational research has not been successful in applying genetic knowledge for the prevention of ID.[1011]

The occurrence of ID in several families is associated with the presence of ID in a family member.[1213] The consanguineous marriages may be playing a crucial role in transferring ID in children from their ID relatives. Primarily, consanguinity is a social factor. Consanguineous marriages are very common in the world.[14] India also has a high rate of consanguineous marriage. The culture and practice of consanguineous marriage varies with geography, religion, and caste in India. The rate of consanguineous marriages is reported to be as high as 40% in the southern states of India.[1115] Parents with or without ID can receive a defective gene of lower cognitive abilities from their parents with ID. Then, they can pass to their children in the form of ID.[141617] The presence of other neurological disorders such as epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and severe mental illnesses in consanguineous relatives has also been found to be associated with ID in various studies.[141819] A clinical study in South India has found that 30% of children with ID were born from parents who had a consanguineous marriage.[1620]

Considering the fact that the family history of ID is itself a potential cause of ID, an attempt should be made to understand the different patterns of consanguineous marriages and the relationship between ID in children with ID in their parents and consanguineous relatives.[1121]

Objective

This study traces common patterns of consanguineous relationship in the parents of ID children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a case series research design. An extreme sampling method was applied. Under this sampling approach, authors selected six cases of ID with a family history of ID and of consanguineous marriage between their parents, from a pool of 262 ID cases aged between 3 and 18 years. These cases were registered in the Integrated Community-based rehabilitation Disability Project Barwani, Asha gram Trust. This project was implemented in 63 remote villages of Barwani district, Madhya Pradesh, India. All cases were receiving rehabilitation services from this project. Asha gram Trust is a nonprofit organization. It has been providing health and rehabilitation services in Barwani and adjoining districts in Madhya Pradesh. The first author was employed with this organization. He was involved in making diagnosis and providing comprehensive intervention to these cases. Data were collected by the first author. The clinical interviews and case history methods were used for data collection. The first author's informal communication, interaction during training with village groups in project area, and information collected through active participant observation were considered in discussion. Out of all cases of consanguineous marriages and a family history of ID, epilepsy, and mental illness, only six cases, representative of all patterns of consanguineous relationship, were selected for this study. The sample represents tribal and nontribal population. The patterns of consanguineous marriages are shown and described with the help of pedigree charts.

RESULTS

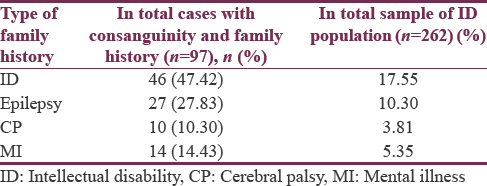

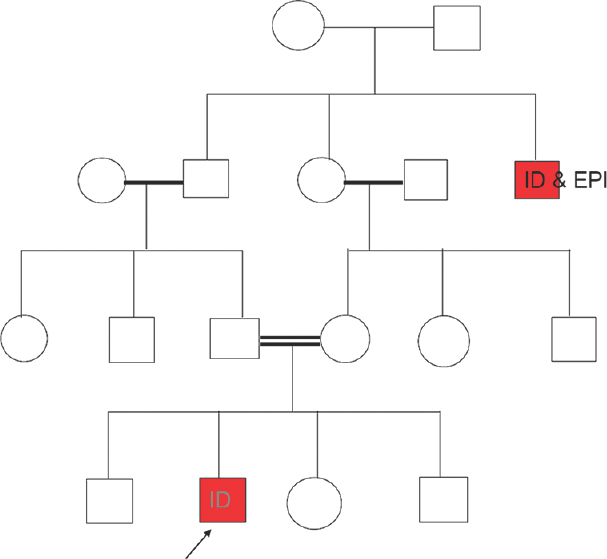

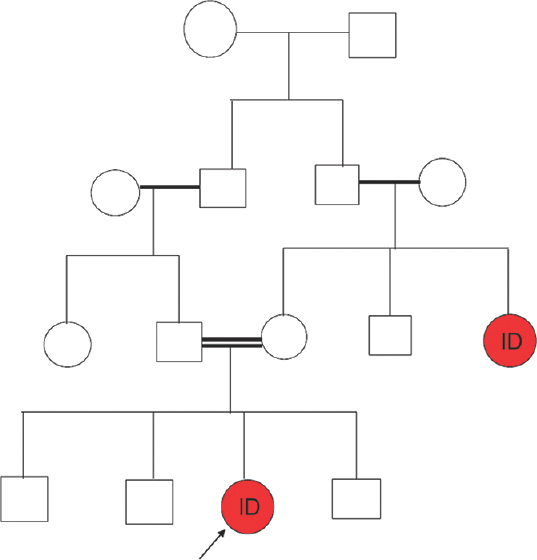

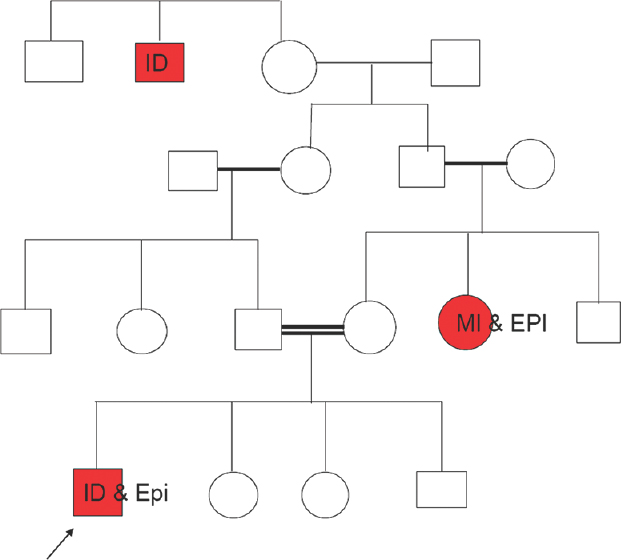

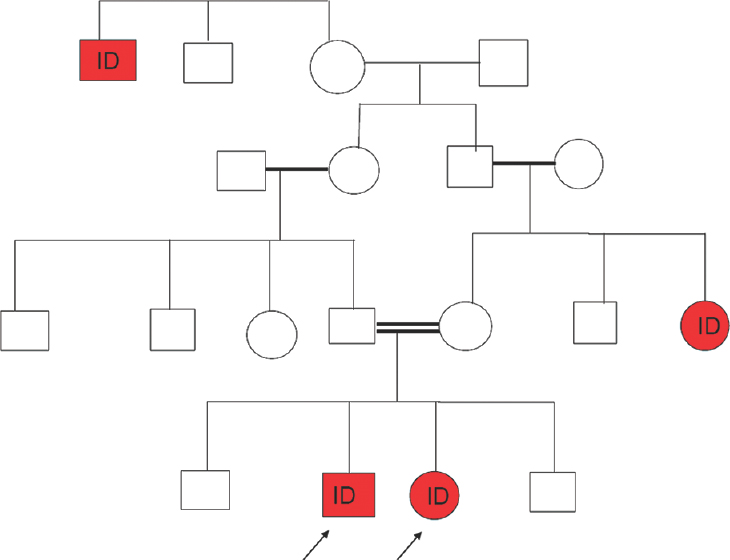

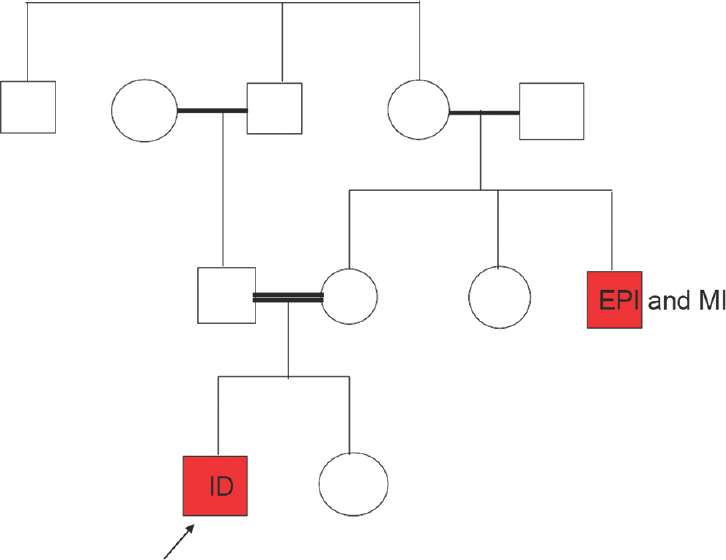

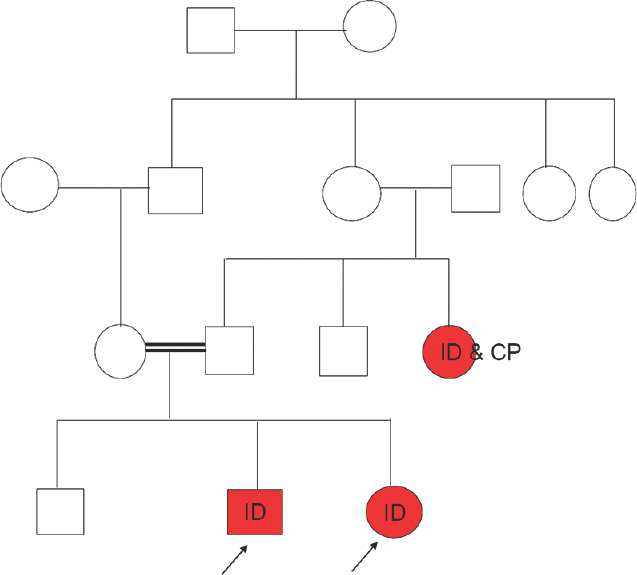

Out of a total of 262 children with ID, parents of 97 (37.02%) children had some form of consanguineous relationship and a family history of at least one disorder from ID, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, and mental illness. Among consanguineous parents, 46 (47.42%) children had a family history of ID, 27 (27.83%) had epilepsy, 10 (10.30%) had cerebral palsy, and 14 (14.43%) had mental illness. Out of the total ID population, 17.55% had a history of ID, 10.30% had epilepsy, 3.81% had cerebral palsy, and 5.35% had mental illness [Table 1 and Figures 1-6].

- History of intellectual disability and epilepsy

- History of intellectual disability

- History of intellectual disability, epilepsy, and mental illness

- History of intellectual disability in third and fourth generations

- History of epilepsy, and mental illness

- History of intellectual disability and cerebral palsy

DISCUSSION

The consanguineous pattern in tribal and nontribal (Hindu) population in our study is consistent with other studies.[11] Like Muslim population, marriages between brother's and sister's children and children of real sisters and real brothers were also found in tribal and nontribal population. Like Muslim population, the preference for the first cousin marriages was observed in Hindus.[2223] The marriage between the children of brother and sister is common in Hindus. However, marriage between the son of sister and her brother's daughter is preferred in Central and North India, whereas marriage between son of brother with his sister's daughter is common in southern states of India. The rate of consanguineous marriages is relatively higher in South India.[1724] Like Hindus and Muslims, consanguineous marriages are equally common in tribal population. Consanguineous marriage equally occurs between son and daughter of brother and sister without any preference in subtribes, such as Bheil, Bhilala, and Barela in Barwani district. Other researchers also found a similar pattern in subtribe Baiga in the state of Madhya Pradesh.[25] Compared to nontribal parents of ID children, the age differences between tribal parents (husbands and wives) were observed higher. In addition, polygamy in tribal males was observed which was rarely noticed in nontribal males. A few marriages between one male with two real sisters were also observed in tribal population. A higher rate of consanguineous marriages in rural nontribal and tribal populations was found consistent with other researchers.[26]

Strength and limitations

The findings of our study are based on a large data which substantially covered nontribal and tribal populations of an underserved geographical area of Central India. This study provides important information about consanguinity and association of family history of four conditions in tribal population which has not been studied previously. This study also has certain limitations. The parents might have had difficulty in differentiating mental illness and ID, cerebral palsy and locomotor disabilities, epilepsy, and psychological/psychiatric disorders because of overlapping/similar presentation. A few parents were unable to provide information about their relatives. A few parents might have overreported or underreported the condition of their relatives and their consanguineous relationship. There are chances that parents may not be aware of their relatives with ID, mental illness, epilepsy, and cerebral palsy who had been died before.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrates an association between consanguinity and family history of ID in tribal and nontribal populations from India. Further research employing a case–control design in consanguineous and nonconsanguineous families is needed to better understand the association between ID and family history. There is also a need to create public awareness related to ill effects of consanguinity and its association with ID.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We wish to sincerely thank Asha gram Trust, India, for allowing us to do this study.

Apart from being consultants in private practice, currently, Rajshekhar Bipeta is also employed as Associate Professor of psychiatry at department of psychiatry, Gandhi Medical College and hospital, and Srinivasa S. R. R. Yerramilli as Associate Professor of psychiatry at department of psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health, Osmania Medical College, Hyderabad, Telangana, India.

REFERENCES

- Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non-syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: An exome sequencing study. Lancet. 2012;380:1674-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genetic basis of non-syndromic intellectual disability: A review. J Neurodev Disord. 2010;2:182-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetics and pathophysiology of mental retardation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:701-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of recent epidemiological studies of mental retardation: Prevalence, associated disorders, and etiology. Am J Ment Retard. 1987;92:243-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consanguinity and early mortality in the Muslim populations of India and Pakistan. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13:777-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- The genetic variability and commonality of neurodevelopmental disease. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160C:118-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1921-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of consanguinity on the Indian population. Indian J Hum Genet. 2002;8:45-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- The clinical profile of mentally retarded children in India and prevalence of depression in mothers of the mentally retarded. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:165-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological and aetiological study of children with intellectual disability in Taiwan. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998;42(Pt 2):137-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consanguinity and its relevance to clinical genetics. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2013;14:157-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of genetic disorders in India and a framework for community control. Public Health Genomics. 2002;5:192-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consanguinity and chromosomal abnormality in mental retardation and or multiple congenital anomaly. J Anat Soc India. 2007;56:30-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case-control study on risk factors of mental retardation from an urban area of North Coastal Andhra Pradesh. J Life Sci. 2010;2:93-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- An analysis of consanguineous marriage in the Muslim population of India at regional and state levels. Ann Hum Biol. 2000;27:163-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sociodemographic correlates of consanguineous marriage in the Muslim population of India. J Biosoc Sci. 2000;32:433-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in consanguineaous marriage in Karnataka, South India, 1980-89. J Biosoc Sci. 1993;25:111-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consanguinity and reproductive behaviour in a tribal population ‘the Baiga’ in Madhya Pradesh, India. Ann Hum Biol. 1995;22:235-46.

- [Google Scholar]