Translate this page into:

A dilemma of syringopleural shunting in an accidentally found asymptomatic lung fibrosis

*Corresponding author: Bheemas B. Atlapure, Department of Anaesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Guwahati, Assam, India. bheemas4atlapure@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Atlapure BB, Karim HM, Dikshit P. A dilemma of syringopleural shunting in an accidentally found asymptomatic lung fibrosis. J Neurosci Rural Pract. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_129_2025

Dear Sir,

Syringomyelia is a neurological condition in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is collected within the spinal cord to form a cavity.[1] The syrinx may expand and cause spinothalamic tract destruction, leading to classic cape-like bilateral pain and temperature loss in the shoulders, arms, and hands.[2] Treatment focuses on reducing fluid accumulation by addressing the root cause by improving CSF flow through decompression, reconstructing the spinal subarachnoid space, or diverting fluid from the syrinx. Post-laminectomy recurrence of the syrinx is frequent, particularly in post-traumatic cases, necessitating shunt placement.[3] Different shunt systems, including the syringosubarachnoid, syringo-peritoneal, and syringo-pleural systems, have been described.[4] Syringo-pleural shunting which offers short-term benefits is preferred because it requires a shorter tube and no positional adjustments during surgery. To our knowledge, the literature reporting challenges in syringopleural shunt placement with or without underlying lung pathology is scarce. Herein, we discuss the case of an asymptomatic patient with lung fibrosis secondary to tuberculosis.

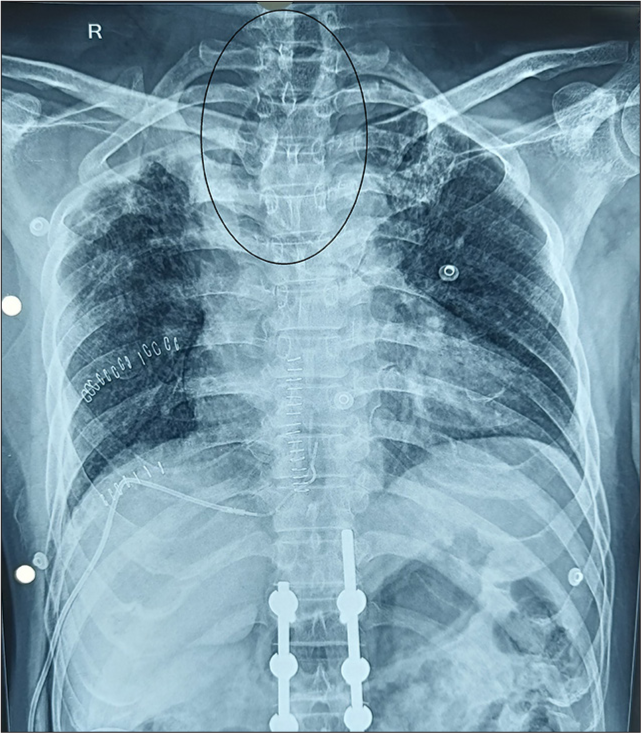

A 50-year-old man with post-traumatic syringomyelia and holocord syringohydromyelia presented with progressive bilateral lower limb dysesthesia and weakness, left upper limb weakness, and cape-like sensory impairment. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was managed with vildagliptin and metformin. Six years earlier, he had sustained a road traffic accident causing an L1 burst fracture treated with D12-L1-L2 pedicle screw fixation and laminectomy. Chest radiography revealed significant tracheal deviation to the right, and computed tomography of the thorax indicated an old-healed tubercular right apical fibrosis [Figures 1 and 2]. Despite the asymptomatic pulmonary status, pleural examination revealed dense fibrosis and adhesions. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a holocord syrinx extending from the corticomedullary junction to the conus medullaris and syringobulbia.

- Chest radiography showing tracheal deviation toward the right (circle).

- Computed tomography of the thorax (a, b) axial view and (c, d) coronal view showing lung fibrosis (circle) and tracheal deviation (arrow).

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia in the prone position. Following D9-D10 laminectomy and midline durotomy, a myelotomy was performed and shunt tubing was inserted into the syrinx. However, dense fibrosis in the pleural space precluded successful syringopleural shunt placement, even after exposing the 7th and 9th intercostal spaces on the same side. As this was unanticipated by the neurosurgeon, further intraoperative communication led to a revised plan for a syringoperitoneal shunt. As the patient was prone and peritoneal access was not possible, we had to change the position of the patient to the left lateral, maintaining sterility midway through surgery. This led to a significant delay in the procedure, as all personnel involved had to be briefed before repositioning the patient. However, the syringoperitoneal procedure was performed with successful completion and uneventful extubation.

This case highlights the dilemma of syringopleural shunting in patients with lung fibrosis, possibly due to past tuberculosis, despite an asymptomatic presentation. Interestingly, fibrosis was primarily apical but posed challenges in the lower intercostal spaces. These findings underscore the importance of considering syringoperitoneal shunts as the primary plan to minimize intraoperative complications and undue strain on the personnel involved in the surgery to reposition the patient midway through the procedure, leading to an increased procedure time. While beneficial, syringopleural shunting is associated with complications such as shunt obstruction, failure, migration, spinal cord tethering, low CSF pressure, and pulmonary issues such as pleural effusion and pneumothorax.[5]

Ethical approval:

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent:

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation:

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41:398-400.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An atypical clinical presentation of post-traumatic syringomyelia: A case report and brief review of the literature. Cureus. 2017;9:e1852.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of posttraumatic syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;17:199-211.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surgical management of post-traumatic syringomyelia. Spine (Phila Pa (1976)). 2010;35:S245-58.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial hypotension after syringopleural shunting in posttraumatic syringomyelia: Case report and review of the literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2015;10:158-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]