Translate this page into:

Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage as initial presentation of dural sinus thrombosis

Address for correspondence: Dr. Shriram Sharma, North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Medical Sciences, Shillong, India. E-mail: srmsims_sharma@rediffmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the older is most often due to aneurismal rupture. Other vascular lesions are known to rarely cause SAH. Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) can be difficult to diagnose because of its wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Its diagnosis can be further complicated when patients initially present with acute SAH. We report a case of dural venous sinus thrombosis with SAH, most probably, due to raised venous pressure draining venous tributaries. A 59-year-old man presented with severe headache. Computerized tomography (CT) scan head was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested right parasagittal fronto-parietal hemorrhage. No aneurysm was detected on magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). MRV revealed superior sagittal sinus (SSS) and lateral sinus thrombosis. DSA showed occlusion of intracranial SSS and lateral venous sinus. The patient improved with anticoagulant therapy. This case highlights the fact that SAH may reveal a CVT, and emphasizes on the inclusion of MRV in the diagnostic workup of SAH, particularly in cases in which aneurysm is not detected.

Keywords

Cerebral venous thrombosis

digital subtraction angiography

magnetic resonance angiography

subarachnoid hemorrhage

Introduction

CVT can be difficult to diagnose, and is further complicated when patients initially present with acute Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).[1] SAH associated with CVT is rarely reported in the literature.[23] Acute SAH suggests the presence of a vascular lesion such as ruptured aneurysm and CVT is not generally considered in the diagnostic workup of SAH.[4] Surprisingly, patients with CVT and radio logic signs of SAH are seldom reported.[56] SAH in these cases is probably due to raised venous pressure of draining venous tributaries.[7] We present the case of a male patient with dural sinus thrombosis (DST), whose initial presentation was SAH. After therapy with subcutaneous low molecular weight (LMW) heparin, the sinus thrombosis resolved.

Case Report

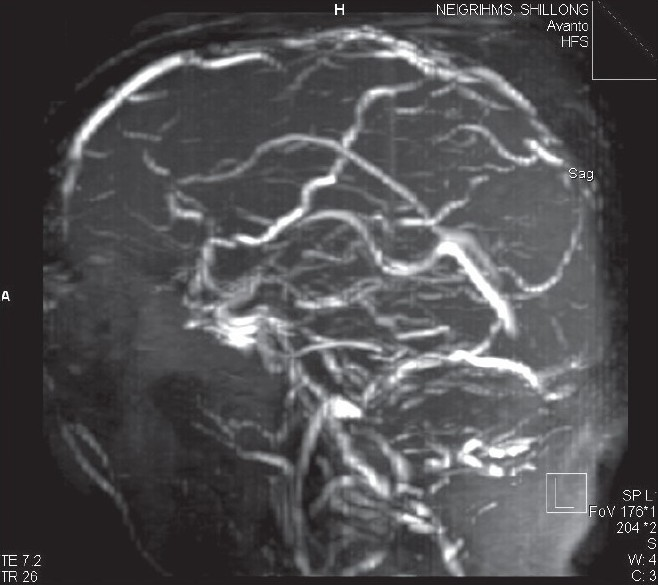

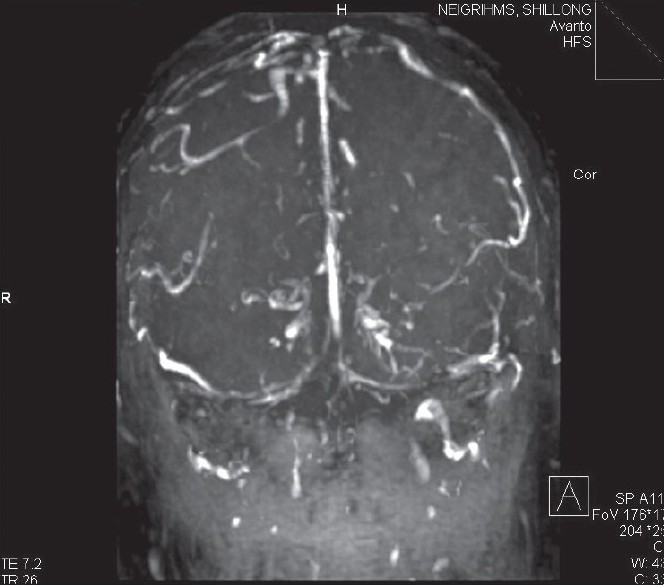

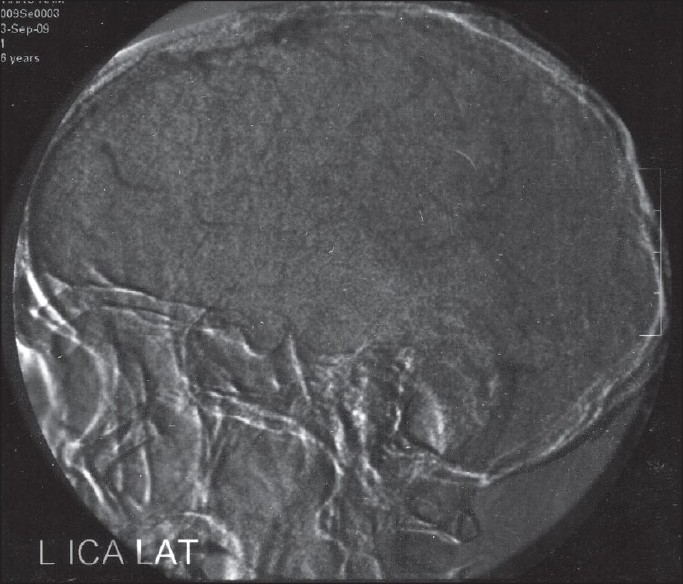

A 59-year-old male patient suffered from rapidly progressive and pulsatile headache over the right parietal region characterized as thunderclap and nausea. He had no fever. These symptoms were followed by generalized seizure. Neurological examination showed a normal level of consciousness. On examination, meningism was seen. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. CT scan head was normal. MRI revealed right parasagittal high fronto-parietal subarachnoid hemorrhage with mild gyral edema. MRV showed superior sagittal sinus and bilateral transverse sinus thrombosis [Figures 1 and 2]. DSA confirmed [Figures 3 and 4] the diagnosis of DST without any potential cause of SAH. Coagulation testing, including prothrombin time, activated prothrombin time, anticardiolipin antibody titer, antiphospholipid antibody titer, homocysteine titer, and levels of protein C and S, antithrombin III, and fibrinogen were all within normal limits and done simultaneously with MRI, MR Venography, DSA within one to two days of admission. Subcutaneous LMW heparin therapy was given. The patient's condition stabilized after nine days of treatment. Oral warfarin maintained an INR of 2.0-3.0. Patient's improvement was clinically satisfactory within six weeks, Repeat DSA done after six weeks was normal, except minimal filling defect. Patient was followed up at two-weeks intervals for three months

- MRI brain showing obliteration of superior saggital sinus

- MRI brain showing oblitertion of transverse sinus in coronal section

- DSA in venous phase revealing obliteration of lateral sinuses

- DSA in venous phase showing fi lling defects in sagittal sinus

Discussion

The spectrum of clinical presentations of CVT ranges from headache with papilledema to focal deficit, seizures and coma. Up to 75% of cases are characterized by focal neurologic deficit and headache; 30-50% of affected patients present with seizures, often followed by Todd's paresis. Rare, but classical, clinical pictures are those of SSS thrombosis (4%) with bilateral or alternating deficits and/ seizures. SAH is related to ruptured aneurysm in 85% of cases[6] and to nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic hemorrhage in 10%; the remaining 5% are related to a variety of rare conditions such as arterial dissection, dural arteriovenous fistula, pituitary apoplexy, and cocaine abuse.[689] In an exhaustive review of SAH, CVT was not listed as a cause of SAH.[8] This omission is rather surprising because erythrocytes are commonly present in the CSF of patients with CVT.[3510] One can speculate that plain CT scan may cause small amounts of subarachnoid blood to be overlooked, especially when the blood is located in the sulci of cerebral convexity or when larger amounts of extravasated blood are present in the sub acute stages.[5] The exact cause of SAH associated with CVT is unknown. Venous hemorrhagic infarct can be responsible for secondary rupture into subarachnoid space and cause SAH.[7] None of the patients reported herein had intraparenchymal signs of bleeding on CT scan or gradient recalled echo (GRE) MRI. DST with secondary venous hypertension may lead to SAH into the subarachnoid space due to rupture of fragile, thin-walled cortical veins.[7] Sinus thrombosis may produce dilatation of the cortical veins, which may rupture and bleed into the subarachnoid space and produce an SAH.[11] A similar mechanism has been proposed to explain the presence of extravasated blood confined to the prepontine or interpeduncular cistern in nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic hemorrhage.[9]

Patients with CVT can present with headache of sudden onset, neck stiffness, and imaging evidence of SAH, simulating a ruptured intracranial aneurysm.[3] The presence of acute SAH of the convexity, especially when basal cistern is spared, should prompted dedicated vascular imaging of both intracranial arteries and dural sinuses.[45] In most institutions, DSA, which remains the criterion standard for detecting cerebral aneurysm, is still part of the systemic workup for patients with acute SAH.[35] Findings in the venous phase of DSA lead to diagnosis of CVT, even if it is previously unsuspected, since noninvasive angiographic techniques are seen to be gradually replacing DSA[3] in the workup of patients with acute SAH. The diagnosis of CVT is becoming more challenging. Indeed, in patients with SAH, a CT or MR angiogram focused on arteries of the circle of Wills does not provide adequate imaging of the distal arteries or the venous system during the same imaging session.[10] Therefore, unless CVT is systematically considered in the diagnostic workup of SAH of the cerebral convexity[57] it could remain undiagnosed when these noninvasive angiographic techniques are used. Dural arteiovenous fistulas, with cortical venous drainage, are at relatively high risk of SAH and have been associated with CVT, presumably because of impairment of cerebral venous drainage.[12]

CVT can be difficult to diagnose because of its wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Diagnosis may be further complicated when patients initially present with acute SAH.[1] The hemorrhage is probably induced by rupture of a dilated vein associated with SSS thrombosis. The location of SAH from SSS thrombosis is usually different from arterial aneurysms.[2] Angiography remains the diagnostic gold standard.[35] Management of venous SAH secondary to CVT is also quite different from that of arterial SAH. Treatment of sinus thrombosis with heparin has long been controversial. The benefits of heparin have been demonstrated in a randomized and placebo-controlled trial of 20 patients.[13] In a further placebo-controlled trail, 60 patients were randomized to either LMW heparin followed by warfarin, or placebo.[14] The anticoagulated patients had better outcomes than the controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. The investigators suggested that anticoagulation was safe, even in patients with cerebral hemorrhage.[14] A subsequent study showed no clear benefit of anticoagulant treatment, but the investigators continued to suggest that there was a non significant trend in favor of anticoagulant treatment.[11] In our patient, the effect of anticoagulation was good. Our patient probably had a hyper coagulation trait, even though the results of available coagulation tests were within normal limits.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage as the initial presentation of dural sinus thrombosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:614-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage: A rare presentation of cerebral venous thrombosis. Headache. 2001;41:889-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolated cortical venous thrombosis presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage: A report of three cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1676-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral venous thrombosis initially presenting with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:282-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-traumatic cortical subarachnoid haemorrhage: diagnostic work-up and aetiological background. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:525-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolated Acute Nontraumatic Cortical Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010

- [Google Scholar]

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage following chronic dural venous sinus thrombosis Angiology. . 2007;58:498-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage: Diagnosis, causes and management. Brain. 2001;124:249-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spontaneous intracranial hypotension with isolated cortical vein thrombosis and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:1413-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome of cognition and functional health after cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Neurology. 2000;54:1687-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of angiographic signs of venous hypertension and clinical signs of intracranial hypertension in intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neuroradiol. 1999;26:49-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of anticoagulant treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30:484-8.

- [Google Scholar]