Translate this page into:

Attitudes toward people with mental illness among medical students

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rohini Thimmaiah, Department of Psychiatry, Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Center, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: drrohinimd@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Globally, people with mental illness frequently encounter stigma, prejudice, and discrimination by public and health care professionals. Research related to medical students’ attitudes toward people with mental illness is limited from India.

Aim:

The aim was to assess and compare the attitudes toward people with mental illness among medical students’.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study design was carried out among medical students, who were exposed (n = 115) and not exposed (n = 61) to psychiatry training using self-reporting questionnaire.

Results:

Our findings showed improvement in students’ attitudes after exposure to psychiatry in benevolent (t = 2.510, P < 0.013) and stigmatization (t = 2.656, P < 0.009) domains. Further, gender, residence, and contact with mental illness were the factors that found to be influencing students’ attitudes toward mental illness.

Conclusion:

The findings of the present study suggest that psychiatric education proved to be effective in changing the attitudes of medical students toward mental illness to a certain extent. However, there is an urgent need to review the current curriculum to prepare undergraduate medical students to provide holistic care to the people with mental health problems.

Keywords

Attitudes

curriculum

medical students

psychiatry

Introduction

Globally, people with mental illness frequently encounter stigma, prejudice, and discrimination not only by the public, but also by the health care providers.[12] According to World Health Organization, it was estimated that there are 450 million people in the world currently suffering from some kind of mental illness and constitutes 14% of the global burden of disease.[3] The prevalence of mental disorders in India is high, as in other parts of the world.[4] It was estimated that at least 58/1000 people have a mental illness and about 10 million Indians suffer from severe mental illness.[56] On the other hand, there is paucity of psychiatrists in India, that is, <0.5/100,000 population.[7]

Published evidence clearly indicates unfavorable attitudes among medical students toward people with mental illness.[89] Further, in a recent study from India, it was found that undergraduate medical students have multiple lacunae in knowledge toward psychiatry, psychiatric disorders, psychiatric patients and psychiatric treatment.[8] In addition, previous research established evidence that psychiatry was not top choice of specialty for medical students.[101112] However, undoubtedly psychiatric experience plays a significant role in changing the attitudes of students toward psychiatry. On the other hand, earlier studies from India indicate that minimum 20–50% of patients attending Primary Health Centers have major mental disorders.[13] Contemporarily, health care professionals can no longer ignore mental health, as it will play an increasingly important role in the care of all patients. Further, the negative attitudes of doctors may compromise the quality of life and self-esteem of patients.[14] Thus, assessing the attitudes of medical students toward mental illness is of greatest concern since they come across patients with different mental health problems. Very few studies from India assessed the impact of psychiatric exposure in changing the attitudes of medical students toward people with mental illness.[151617] It is therefore, the present study was aimed to examine the attitudinal differences between students those have undergone psychiatric training exposure and those who have not, toward people with mental illness.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study carried out at a private medical college, South India.

Participants were selected through convenient sampling. Study criteria included; (a) medical students (1st and 2nd year medical students) those did not have psychiatry exposure, (b) final year students those undergone theory and clinical rotation including 2 weeks of internship, (c) students those were willing to participate. A sample of 193 students (1st and 2nd year n = 126, the final year n = 67) was eligible to participate in the study. However, we could not meet six of the final year students and five of the students from 1st to 2nd year were absent during data collection. Six of the questionnaires were incomplete. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 176 students (n = 115, 1st and 2nd year and 61 final year) with 91.1% response rate.

Measures

Demographic data survey instrument

The demographic form consists of five items to seek the background of the participants in the study that include “age, education, residence, and contact with mental illness.”

Attitude scale for mental illness

This was a valid and reliable (Cronbach's Alpha 0.86), self-report measure used to measure health professionals attitudes toward persons with mental illness.[18] This modified version of the questionnaire measures opinions about mental illness in Chinese community. This was a 5-point Likert scale rated participants responses from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (5). The lower scores indicate positive attitudes toward persons with mental illness.

Separatism

Includes ten items, (1–9, and 24) to measure respondents’ attitude of discrimination e.g.: “People with mental illness have unpredictable behaviour.”

Stereotyping

Includes four items (10–13) intended to measure the degree of respondents’ maintenance of social distance toward persons with mental illness. E.g.: “It is easy to identify those who have a mental illness.”

Restrictiveness

Composed of four items (14–17), that hold an uncertain view on the rights of people with mental illness. E.g.: “It is not appropriate for a person with mental illness to get married.”

Benevolence (reverse coded)

Includes eight items (18–23, 25 and 26) related to kindness and sympathetic views of the respondents toward people with mental illness e.g.: “People with mental illness can hold a job.”

Pessimistic prediction

Composed of four items (27–30) intended to measure the level of prejudice toward mental illness e.g.: “It is harder for those who have a mental illness to receive the same pay for the same job.”

Stigmatization

Includes four items (31–34) that measure the discriminatory behavior of the students toward mental illness.

Procedure

Data was collected a batch-wise in their classrooms after completion of the regular lectures. On the introduction, the primary author explained briefly about aims and methods of the present study to all the participants. Students those were willing to participate were asked to complete the questionnaires. They could complete both questionnaires in about 20 min. Data collection tools contained no identifying information (such as name, address, mobile number, etc.,) and therefore kept the individual responses confidential.

Ethical considerations

Permission was obtained from the administrators of the colleges where the study was conducted. Participants were introduced to the aims and procedures of the study to decide if they would like to participate. After they had agreed to participate verbally, the researchers gave them the confidential questionnaire. Participants were given freedom to withdraw from the study at any part of the procedure.

Statistical analysis

The response of the benevolence domain was reverse coded before the analysis. The data were analyzed using appropriate statistical software and results were presented in narratives and tables. The t-test was used to determine whether significant differences existed between medical and nursing students regarding mean attitudes scores. Chi-square test was used to find the significant association between sociodemographic variables. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

Results

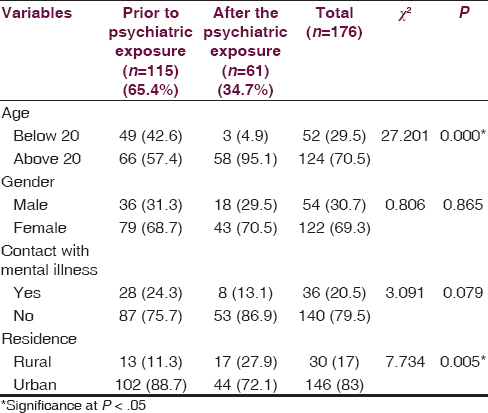

The present study sample comprised of 176 medical undergraduates, of whom 65.4% (n = 115) were (from 1st and 2nd year medical students) were not exposed to psychiatry training. Obviously, more number (42.6%) of the students from 1st to 2nd year were below 20 years old (χ2 = 27.201, P < 0.000). A majority of students were females (69.3%) and unfamiliar about persons with mental illness (79.5%). A significant association (χ2 = 7.734, P < 0.005) was found between rural and urban participants as majority (83%) were from urban background [Table 1].

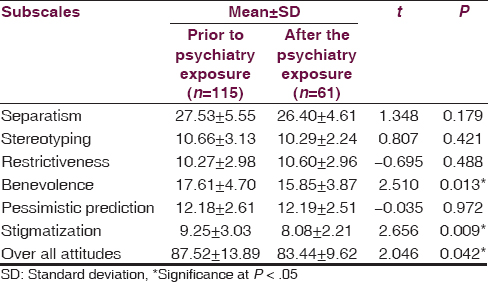

Table 2 demonstrates the comparison of medical students’ attitudes toward mental illness between pre- and post-exposure to psychiatry. The mean score of the medical students after exposure to psychiatry (15.85 ± 3.87) was less than the students who did not have (17.61 ± 4.70) in the benevolence domain (t = 2.510, P < 0.013). These findings indicate that students after completing psychiatry course hold more benevolent attitudes toward people with mental illness. Similarly, students prior to psychiatry exposure had more stigmatizing attitudes (9.25 ± 3.03) toward people with mental illness than final year students (8.08 ± 2.21, t = 2.656, P < 0.009). However, significant differences were not observed between the students’ attitudes toward mental illness in separatism, stereotyping, restrictiveness and pessimistic prediction domains. None the less, the overall mean score on the attitude scale for mental illness showed the significant differences between the students those undergone psychiatry course and those do not (t = 2.046, P < 0.042). These results suggest that medical students’ attitudes changes after exposure to psychiatry as their mean score (87.52 ± 13.89) was lesser compared with the students those did not have psychiatry exposure (83.44 ± 9.62).

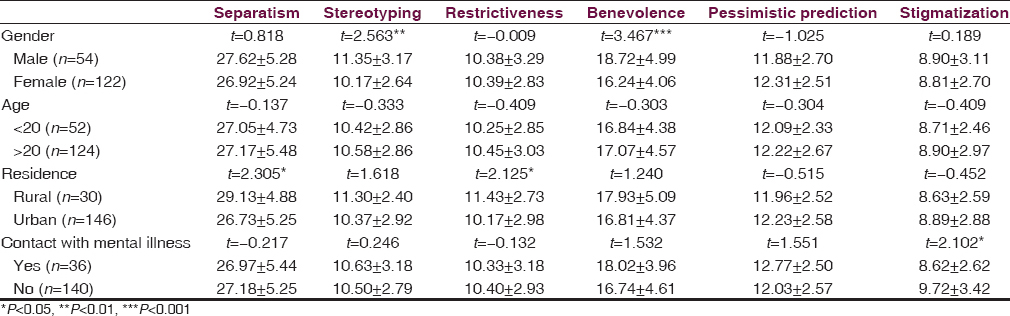

Gender-wise analysis revealed that female participants were less stereotype (t = 2.563, P < 0.01) and more benevolent (t = 3.467, P < 0.001) than male students toward people with mental illness. Medical students from urban had more positive attitudes in separatism (t = 2.305, P < 0.05) and restrictiveness (t = 2.125, P < 0.05) domains than students from rural background. A significant difference was observed between the students those have familiar with mental illness and those were not (t = 2.102, P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Discussion

The present study was one of the most recent studies from India that examined the impact of psychiatry education in changing the attitudes of medical students toward people with mental illness. The findings of the current study suggest that the students those have undergone psychiatry course hold more positive attitudes toward people with mental illness in benevolence and stigmatization domains. However, there were no significant difference observed between the students in separatism, stereotyping, restrictiveness and pessimistic prediction domains. Nonetheless, the overall mean attitude score was less among the students after exposure to psychiatry.

In line with previous research,[1619] our study also demonstrated improvement in medical students’ attitude towards people with mental illness in benevolent and stigmatization domains. There were no statistically significant differences were observed in separatism, stereotype, restrictiveness, and pessimistic prediction domains. In a recent study from Iran demonstrated medical students’ intolerant attitudes toward having close relationships,[20] did not accept to be willing to work[21] with people with mental illness. However, majority of students stated that people with mental illness are treatable.[20] Unfortunately, in the current study, medical students after their psychiatry exposure had negative attitudes toward treatment and rehabilitation of people with mental illness. Our findings support previous studies that revealed more unfavorable opinion about treatment of people with mental illness among medical students and doctors.[21]

In the current study, women than men were more benevolent and less stereotype toward people with mental illness. Our findings support earlier research that indicate more empathy among women toward people with mental illness.[2223] However, few studies did not exhibit more positive attitudes among women with a few exceptions towards people with mental illness.[2024] Our study demonstrated attitudes that are more favorable among students from rural than from the urban background. Similarly, few international studies proved that schizophrenia has a better prognosis in low-income countries and in rural settings. However, in a recent study, urban Indians were not wishing to work with a person with mental illness than rural Indians.[25] Our study found a strong relation between contact with mental illness and stigmatization attitudes toward mental illness. This finding was in line with previous studies that claimed contact with people with mental illness might positively influence students’ attitude toward mental illness.[2126] However, there was a significant difference between students on over all mean score indicate positive attitudes among the students those undergone psychiatry course. Our finding was in line with earlier research.[1517202227] Contrary to these findings in a recent study it was found that better attitudes among interns toward people with mental illness compared to fresh graduate students only in some areas.[16] Similarly, though positive attitudes were found among final year medical students, their beliefs were not changed after psychiatry exposure and this finding was similar to other studies.[28] However, recent studies from India showed negative attitudes among medical students toward people with mental illness.[8161929] Further, these findings support earlier researchers opinion that current curriculum for medical undergraduates has minimal impact in influencing medical students attitudes positively toward people with mental illness.[1619] Few studies indicate that 4-week and 8-week clinical rotation in psychiatry resulted in increased mean attitudinal score among medical students.[2223] Further, Manohari et al. rightly suggested that clinical posting should be parallel to the theory classes. Further, preparation of undergraduates to practice psychiatry at primary care level has to be focused.[30] However, quality of the teaching, enthusiasm of the clinical teachers, the holistic approach and scientific basis of psychiatry are the important factors that influence the students’ attitudes toward psychiatry.[31] Previously published research also provided evidence that brief educational interventions may alter stigmatizing negative attitudes toward mental illness in nursing and medical students in low- and middle-income countries.[32]

Limitations

The present study has certain limitations such as cross-sectional descriptive design, small and convenient sample from a single university made difficult to generalize the findings. Further, the same group has to be observed for the attitudinal changes among students toward people with mental illness. Hence, future studies to be focused on a larger sample and long prospective studies with mixed methodologies may be useful to understand in depth about this phenomenon. Despite of these limitations, present study findings may be useful in revising the current curriculum and teaching methodologies in specific domains. Therefore, educators may focus on negative attitudes of medical students toward people with mental illness in various domains.

Conclusion

In nutshell, our findings revealed that medical students’ attitudes were improved after psychiatry exposure. However, statistically significant differences were found merely in benevolence and stigmatization domains after training. This clearly indicates that respondents attitude of discrimination, maintenance of social distance toward persons with mental illness, an uncertain view on the rights of people with mental illness and the level of prejudice toward mental illness do not change much even after training. This issue needs to be addressed. In line with previous research,[15] the findings of the present study strongly suggest that there is an urgent need to review the current curriculum, number of theory and practical classes, bed side training, duration of training and number of marks allotted to the psychiatry subject in the final exams. There is a need to prepare medical undergraduates to diagnose and treat people with mental illness effectively.

Acknowledgment

The researchers thank all the participants for their valuable contribution.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Public stigma in health and non-healthcare students: Attributions, emotions and willingness to help with adolescent self-harm. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:107-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental illness: Diagnostic title or derogatory term? (Attitudes towards mental illness) Developing a learning resource for use within a clinical call centre. A systematic literature review on attitudes towards mental illness. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:684-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhgap) 2008. Available from: http://www.whoint/mental_health/mhgap/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- Community beliefs about causes and risks for mental disorders: A mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56:606-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Undergraduate medical students’ attitude toward psychiatry: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:37-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigmatising attitude of medical students towards a psychiatry label. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2008;7:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors related to choosing psychiatry as a future medical career among medical students at the faculty of medicine of the University of Indonesia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2012;22:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which students will choose a career in psychiatry? Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:605-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges and opportunities for consultation-liaison psychiatry in the managed care environment. Psychosomatics. 1997;38:70-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Powerlessness, marginalized identity, and silencing of health concerns: Voiced realities of women living with a mental health diagnosis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2009;18:153-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of psychiatric education and training on attitude of medical students towards mentally ill: A comparative analysis. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:22-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of psychiatry training on attitude of medical students toward mental illness and psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:271-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does psychiatry rotation in undergraduate curriculum bring about a change in the attitude of medical student toward concept and practice of psychiatry: A comparative analysis. Ind Psychiatry J. 2012;21:144-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex differences in opinion towards mental illness of secondary school students in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:79-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric curriculum and its impact on the attitude of Indian undergraduate medical students and interns. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32:119-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- How mental illness is perceived by Iranian medical students: A preliminary study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2013;9:62-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Doctors’ attitude towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:931-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of a psychiatry clinical rotation on the attitude of Nigerian medical students to psychiatry. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2012;15:185-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of a clinical posting in psychiatry on the attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry and mental illness in a Malaysian medical school. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:505-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender differences in public beliefs and attitudes about mental disorder in western countries: A systematic review of population studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21:73-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stigmatization of severe mental illness in India: Against the simple industrialization hypothesis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:189-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familiarity with mental illness and social distance from people with schizophrenia and major depression: Testing a model using data from a representative population survey. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:175-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:934-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical students’ attitudes toward mental disorders before and after a psychiatric rotation. Acad Psychiatry. 2005;29:357-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- How to teach psychiatry to medical undergraduates in India?: A model. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35:23-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Familiarity breeds respect: Attitudes of medical students towards psychiatry following a clinical attachment. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18:348-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes toward mental illness and changes associated with a brief educational intervention for medical and nursing students in Nigeria. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38:320-4.

- [Google Scholar]