Translate this page into:

Down syndrome in tribal population in India: A field observation

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ram Lakhan, Department of Epidemiology, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS, USA. E-mail: ramlakhan15@gmail.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Down syndrome (DS) is a prevalent genetic disorder in intellectual disability (ID) in India. Its prevalence in tribal population is not known.

Aims:

The study aimed to understand the profile of DS in a tribal population with an objective of finding the prevalence of DS among those with ID.

Settings and Design:

This is a community-based study with a survey design.

Subjects and Methods:

A door-to-door survey was conducted by trained, community-based rehabilitation workers under close supervision of multidisciplinary team to identify people with ID. A standardized screening instrument National Institute for Mentally Handicapped-Developmental Screening Schedule was used in the survey. All identified ID cases were evaluated by therapists in IDs for diagnosis of ID on developmental screening test and Vineland social maturity scale. Clinical examination was performed by medical doctors for DS on people identified as ID. Only two parents brought their children for further lab investigations at Ashagram Trust, Barwani.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics was applied manually to treat the data.

Results:

The frequency of DS population in tribal population closely matches with DS prevalence in the USA. Mothers of DS children in the tribal community are relatively younger.

Conclusion:

Prevalence of DS in tribal population of India may greatly vary with that of the US data, but it is markedly associated with younger maternal age. Further studies are needed for prevalence and identification of potential correlates of this condition.

Keywords

Down syndrome

genetics

India

intellectual disability

tribal

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is one of the leading genetic causes of intellectual disability (ID) in the world.[1] DS alone accounts 15–20% of ID population across the world.[2] This condition arises from certain types of disturbance in genetic mechanism that leads to the development of an extra chromosome. DS are classified into three main categories. Trisomy, which is the most common type and accounts for 95% of the total DS population. Translocation and mosaic are less prevalent; these accounts for 3% and 2%, respectively.[3] People with DS are susceptible to various chronic disorders, infections, and disabilities. Among all developmental disabilities such as Autism, Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorders, and IDs, the IDs are highly prevalent in DS population. According to the studies conducted in the Western countries, 75% DS population suffers from hearing loss, 50–75% with sleep disorders and ear infection, 60% eye disease, 22% psychiatric disorders, and 50% from heart diseases.[456] The frequency of DS was observed 1 per 1150 in a survey of 94,910 newborns in three metropolitan cities of India: Mumbai, Delhi, and Baroda.[7] Genetic disorders including DS are becoming a common cause of mortality in urban newborns.[8] Cross-cultural studies have shown consanguineous marriages, high birth rate, and advance maternal age as well of fathers’ at conception have a greater risk for DS.[189] Chemical exposure to the parents, radiation during pregnancy, and socioeconomic factors - parental education and place of living, and risk behavior of fathers’ such as smoking are potential attributes of DS aneuploidy.[101112] Because tribal population suffers with higher social, biological, and environmental risks of DS compared to rural and urban population in India, there is a chance this population might show higher prevalence rate of the condition. Estimation of DS prevalence in the overall population is highly needed in India for planning of services and management purpose. This need is higher for tribal and rural population that faces scarcity of genetic counseling, rehabilitation, medical, educational, and welfare services.[8] However, there is a need for robust data from Indian population. Therefore, this study was conducted to describe the profile and frequency of DS population of a tribal village and compare it with global data.

Aim and objectives

The study aimed to understand the profile of DS in tribal population with two objectives: (1) To find the prevalence of DS in tribal population and (2) its comorbidity with ID in tribal population.

Subjects and Methods

The study was conducted in Chikhalia, a tribal village in Barwani Block of Barwani district in the state of Madhya Pradesh, India. This village has 99.9% tribal population. Approximately, 95% population of this village lived below the poverty line in 2000. Ashagram Trust (AGT), a nongovernment organization, provides services to the people with ID and mental illnesses of this village under a community-based approach. This village is geographically spread in a radius of 4 km and had a population of 2767. The village was selected based on the prior work of the first author who worked extensively in this area in association with the said organization, which is running several community-based programs and has a good rapport with community. The village was surrounded by six tribal villages (Vedpuri, Menimata, Temla, Sindhikhodri, Rasgoan, and Hirachrai) in all four directions and most of the houses of this village were approachable through motorcycle or up to half an hour walk from the place where path ended for the motorcycle. A door-to-door survey was conducted by the community-based rehabilitation workers under the close supervision of therapists in IDs for identification of people with ID. A standardized valid and reliable instrument, “National Institute for Mentally Handicapped-Developmental Screening Schedule” was used in this survey.[13] Children identified as ID in screening survey were assessed by two therapists in ID on standardized tests developmental screening test and Vineland social maturity scale for the diagnosis purpose.[13] The comorbid conditions were also assessed by the same ID professionals and also by a psychiatrist for medical conditions such as epilepsy and psychiatric disorders. Clinical/physical examination is considered a first and most sensitive method for the provisional diagnosis of DS.[414] Children diagnosed as having DS on the basis of clinical examination by an ID professional (first author) and also by a psychiatrist were referred to the medical lab situated in AGT hospital at AGT campus, Barwani. The ID professional was assigned by the AGT to this village for providing and arranging comprehensive services. Two out of four parents were able to bring their children for lab testing. One parent migrated to the Gujarat for seasonal employment and was away from that village for over 6 months. Their blood samples were collected by a licensed lab technician in AGT hospital medical lab and sent to a tertiary laboratory-based hospital, in Baroda, with the help of attending physician in AGT hospital for chromosome evaluation. Children diagnosed as DS are discussed in this paper in reference of the population of that village in that year. The prevalence rate of this population is calculated manually.

Results

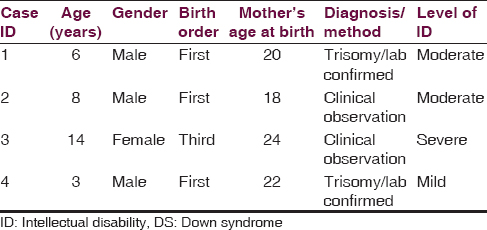

Table 1 provides the profile of children with DS. First three cases (1, 2, and 3) were identified in the survey, while one child (case ID number 4) was identified in the process of community capacity building exercise within the community. The frequency/prevalence of DS (4/2767 = 0.00145) equals (0.00145 × 1000), 1.45/1000 in tribal population. Considerably, all mothers of all identified DS children were in their young age (18–24 years); when they had babies with DS.

A separate analysis also indicates that 75% children were on the first birth order. None of the parents of children with DS had consanguineous marriage or history of DS, ID, or any other neurological disorder such as cerebral palsy and epilepsy in preceding generation.

Discussion

Frequency of DS in the tribal population of this village was observed slightly higher than the reported prevalence rates (0.81–1.2/1000 live births) in India.[15161718] However, this frequency closely matches with the US prevalence for DS (1.43/1000 person).[1920] Interestingly, against the odd, mothers of these children were relatively younger, while the DS prevalence highly associates with advance maternal and maternal grandparents’ age in the population.[15] Studies conducted on urban population of Hyderabad and Mumbai city and the state of Punjab found a similar association of younger maternal age (mean age 30 years) with DS.[152122232425] We also observed that 75% children were on the first birth order. None of the parents of these DS children had consanguineous marriage or history of DS, ID, or any other neurological disorder such as cerebral palsy and epilepsy in preceding generation. Then, it is very intriguing to further explore the factors that contribute to the condition. There is very limited knowledge exists about the prevalence and determinates of DS in India for tribal as well nontribal population for comparing the findings of this study. Therefore, it is hard to say that tribal population has a higher prevalence rate of DS. However, it is known that tribal population is highly impoverished and disadvantaged in several ways and suffers proportionately higher burden of nutritional and genetic disorders,[2627] which are potential factors for DS and because of those factors, this population may be having a higher rate of DS in India. Consanguineous marriages, high birth rate, advanced age of parent/s, chemical exposure, and second-hand smoke may be other contributing factors in tribal.[189101112] However, this study has specific limitations, which need to be carefully considered before generalizing the findings: A small sample size is the main limitation of this observation. In tribal population, people are not well accustomed for keeping the record of their age. Hence, age of the mothers and children is based on the best estimation. This estimation was done by talking with individuals and also their family members and referring the time with local events and factors, such as who was the village Sarpanch of that village at that time. This population transit heavily within and surrounding districts, as well seasonally migrate for employment to nearby states: Gujarat and Maharashtra, which may be another confounder associated with this observation.

Conclusion

Prevalence of DS in tribal population of India may greatly vary with that of the US data, but it is markedly associated with younger maternal age. Further studies are needed for prevalence and identification of potential correlates of this condition.

Acknowledgment

Authors sincerely thank AGT for allowing them to work with this population, community workers for identification and data collection, children with DS, and their parents in the participation of this research. They also thank Action Aid, for their financial support.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Down syndrome and genetics – A case of linked histories. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:137-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding Intellectual Disability and Health. Down Syndrome. Available from: http://www.intellectualdisability.info/diagnosis/downs-syndrome/

- [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics. 2011;128:393-406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Down syndrome and associated medical disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1996;2:85-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders in persons with Down syndrome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:609-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying Regional Priorities in the Area of Human Genetics in SEAR: Report of an Intercountry Consultation, Bangkok, Thailand, 23-25 September, 2003. New Delhi: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia, (SEA-RES-121); 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnic differences in the impact of advanced maternal age on birth prevalence of Down syndrome. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1778-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible risk factors for Down syndrome and sex chromosomal aneuploidy in Mysore, South India. Indian J Hum Genet. 2007;13:102-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case-control study of paternal smoking and birth defects. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:273-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;127:734-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying children with intellectual disabilities in the tribal population of Barwani district in state of Madhya Pradesh, India. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2015 DOI: 10.1111/jar.12171

- [Google Scholar]

- Early detection of podiatric anomalies in children with Down syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95:17-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of advanced age of maternal grandmothers on Down syndrome. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of malformations and Down syndrome in India (SOMDI): Delhi region. Indian J Hum Genet. 1998;4:84-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of malformation and Down syndrome in India (SOMDI): Baroda region. Indian J Hum Genet. 1998;4:93-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88:1008-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current estimate of Down syndrome population prevalence in the United States. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1163-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytogenetic studies of 1001 Down syndrome cases from Andhra Pradesh, India. Indian J Med Res. 2000;111:133-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal age and chromosomal profile in 160 Down syndrome cases – Experience of a tertiary genetic centre from India. Int J Hum Genet. 2002;2:49-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytogenetic profile of individuals with mental retardation. Int J Hum Genet. 2003;3:13-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mean maternal age of Down's syndrome in Hyderabad, India. J Indian Med Assoc. 1999;97:25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parental age and the origin of extra chromosome 21 in Down syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2001;46:347-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Socioeconomic effects on the risk of having a recognized pregnancy with Down syndrome. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:522-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood groups, hemoglobinopathy and G-6-PD deficiency investigations among fifteen major scheduled tribes of Orissa, India. Anthropologist. 2004;6:69-75.

- [Google Scholar]