Translate this page into:

Barriers to Disclosure of Intimate Partner Violence among Female Patients Availing Services at Tertiary Care Psychiatric Hospitals: A Qualitative Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mysore Narasimha Vranda, Department of Psychiatric Social Work, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Institute of National Importance, Bengaluru - 560 029, Karnataka, India. E-mail: vrindamn@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Intimate partner violence (IPV)/domestic violence is one of the significant public health problems, but little is known about the barriers to disclosure in tertiary care psychiatric settings.

Methodology:

One hundred women seeking inpatient or outpatient services at a tertiary care psychiatric setting were recruited for study using purposive sampling. A semi-structured interview was administered to collect the information from women with mental illness experiencing IPV to know about their help-seeking behaviors, reasons for disclosure/nondisclosure of IPV, perceived feelings experienced after reporting IPV, and help received from the mental health professionals (MHPs) following the disclosure of violence.

Results:

The data revealed that at the patient level, majority of the women chose to conceal their abuse from the mental health-care professionals, fearing retaliation from their partners if they get to know about the disclosure of violence. At the professional level, lack of privacy was another important barrier for nondisclosure where women reported that MHPs discussed the abuse in the presence of their violent partners.

Conclusion:

The findings of the study brought out the need for mandatory screening of violence and designing tailor-made multicomponent interventions for mental health care professionals at psychiatric setting in India.

Keywords

Barriers

disclosure

intimate

tertiary care

violence

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is widely recognized as a significant global problem, a major public health issue,[12] and one of the most widespread violations of human rights.[3] The World Health Report on Violence and Health[4] reports that 10%–69% of women report being physically assaulted by an intimate male partner at some point in their lives, these findings were published after conducting 48 population-based surveys around the world. In India, there is no national-level data regarding the extent and magnitude of this problem. The National Family Health Survey[5] findings report that overall one-third of women aged 15–49 years have experienced physical violence and about 1 in 10 have experienced sexual violence. In total, 35% have experienced physical or sexual violence. This figure translates into millions of women who have suffered, and continue to suffer, at the hands of husbands and other family members. One in four married women have experienced physical or sexual violence by their husband in the 12 months preceding the survey. This survey finding underscores the extent and severity of violence against women in India, especially married women.

The mental health consequences of IPV have received extensive research attention. Many studies have documented the relationship between IPV and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol abuse, depression, anxiety-related problems, and alcohol abuse problems among women experiencing domestic violence.[67] Female patients with mental illness are at greater risk of IPV, but little is known about their forms, health impact, disclosure, and help-seeking behaviors. A recent study by Khalifeh et al.[8] on IPV among person with chronic mental illness (CMI) revealed that past-year IPV was reported by 21% and 10% of women and men with CMI, respectively. Persons with CMI, especially women, were two to five times more likely to experience emotional, physical, and sexual IPV as those without. The highest relative odds were found for sexual IPV against women; 30 in 1000 women with CMI reported sexual assault by a partner in the past year compared to 4 in 1000 women without CMI. People with CMI were more likely to attempt suicide as a result of IPV, were less likely to seek help from informal networks, and were more likely to seek help exclusively from health professionals.

In India, there is not many studies related to IPV among women with mental illness, health outcome, and disclosure-related issues in mental health settings. Chandra et al.[7] reported that compared to women without a history of IPV, the women with a history of IPV reported higher depression and PTSD, and the severity of violence and sexual coercion correlated positively with PTSD severity. Many times, women experiencing IPV do seek external help, especially from health-care providers, due to various social, cultural, and professional barriers. When it comes to mental health settings, women hardly disclose their distress secondary to IPV. The barrier and facilitations for not disclosing IPV to mental health service providers in tertiary care settings are yet to be explored. The current research is a first study at a mental setting in India directed toward exploring barriers in disclosing IPV to mental health professionals (MHPs) of multidisciplinary team (such as psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, and clinical psychologists) by women with mental illness experiencing IPV at a tertiary care psychiatric hospital.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

The present research was a cross-sectional study. Women availing inpatient or outpatient services in Adult Psychiatry at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) hospital located in Bengaluru, South India, were considered for the study. NIMHANS is a premier teaching and training institute in the country having 850 beds. Patients come either directly or through referral from all over the country, especially from South India. A sample of 100 women with a history of abuse was selected using purposive sampling with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were (a) Female patients aged between 18 and 55 years, (b) female patients who speak Kannada and English, (c) those female patients who were under remission without active psychopathology, vocal, and able to participate in the interview. Exclusion criteria were female patients with mental retardation, substance abuse disorders, and organic psychiatric disorders. The study was carried during January 2017–October 2017.

The participants were briefed about the study and informed consent was sought. Written consent was obtained from all participants confirming their willingness to participate in the study. All women were assured confidentiality and were interviewed in complete privacy in the interview/counseling rooms at the hospital. The background information of the women was collected. They were asked if they had ever been asked questions about IPV during their visit in mental health hospital by MHPs. Out of 100, 62 women reported that their MHPs had asked them for IPV and 38 women had never been asked IPV in a regular mental health-care visit. Ten women were voluntarily disclosed about IPV to MHPs in their regular mental health-care visit. The ages of the participants ranged between 18 and 56 years with a mean age of 34.2 years (standard deviation = 8.97). Majority (91%) of the women were educated, 28.3% were employed, and 71.7% were homemakers. Nearly 55% of women were married, 28% were separated, 13% were divorced, and 4 % were single.

A qualitative descriptive approach using semi-structured interview was used to collect the information from women with mental illness experiencing IPV about help-seeking behaviors of voluntary/involuntary disclosure of IPV to MHPs, reasons for disclosure/nondisclosure of IPV, feelings experienced after reporting IPV and responses, and help received from the MHPs following the disclosure of violence. The interviews conducted in Kannada were audio recorded. Field notes were made immediately after each interview. The audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and both the transcriptions and field notes were translated into English. The researcher's personal observations about the interviews were also recorded as memos. The content analysis was done for the qualitative data. The researcher made a free list of frequently occurring responses for each of the questions reported by the respondents. Following the technique of iteration, the researchers went over these responses, removed overlapping responses, and ranked and listed according to the frequently occurring responses for each of the questions in the interviews. A final list of responses of the women for the questions was made using frequency analysis. The quotes of the respondents were also mentioned in the results to provide the descriptive understanding of the women's reasons for disclosure and nondisclosure of IPV and their perceptions in relation to responses of MHPs following disclosure of violence in clinical setting.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the Institute Ethical Committee – Behavioural Sciences Division of the NIMHANS (Ref: NIMHANS/1st IEC [BEH. Sc. DIV.2016]).

RESULTS

The women were asked if they had ever been asked questions about IPV during their visit in mental health hospital by MHPs. Out of 100, 62 women reported that their MHPs had asked them for IPV and 38 women had never been asked IPV in a regular mental health-care visit. Ten women voluntarily disclosed about IPV to MHPs in their regular mental health-care visit. The results of reasons for the voluntary disclosure, barrier for nondisclosure, perceptions of feelings associated postdisclosure, and responses of MHPs perceived following the disclosure of IPV are presented below:

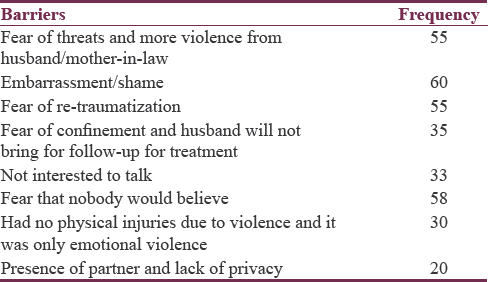

Barriers/reasons for nondisclosure of intimate partner violence to mental health professionals

As mentioned earlier, a large proportion (62%) of women who had experienced IPV did not disclose their suffering to MHPs. The most frequently mentioned reasons why female victims withhold disclosure of IPV were the highest [Table 1] in the categories of embarrassment or shame and the fear they would believe. They also reported fear of threat and further violence from the husbands/mothers-in-law. Many women also did not want to recall what they had undergone/been experiencing to MHPs due to fear of re-traumatization. Less often reported reasons for nondisclosing IPV were women did not want to talk about it anymore as they felt nothing can be done to their situation, some women were unable to recognize that they had undergone violence since they had no injuries due to physical violence and it was only emotional violence, and few women also expressed fear of confinement from husbands if they get to know about disclosure of violence and worried that husband would not bring them to hospital for follow-up treatment.

“I don’t want recall, if I share about it (violence), I will become more fearful, will not get sleep, I will be getting constant headache”

“How can I disclose it doctor? My husband was sitting along with me. After going home he will beat me more”

“I was hesitant to talk.because my elder son accompanies me for my hospital visit. I embarrassed to speak infront of him”

“I know what I have been going through since after my marriage, nobody can understand it, because, my husband behaves in such a way that, people should think as I am the worst wife and responsible for everything he does to me”

“I was scared because of my mother in law, she was there with me, if doctor ask her about it then, I will be caught up by both of my husband and in law…so I didn’t share.”

Reasons for voluntary disclosure of intimate partner violence to mental health professionals

The reasons for voluntary disclosure of IPV by a small percentage (10%) of women to MHPs were as follows: they were unable to tolerate the pain and trauma due to violence, five were severely undergoing violence since marriage, and five women just wanted to share to someone what they are undergoing in order to feel themselves better.

“I just wanted to share to someone to feel better, I told to doctor”

“I was not able to tolerate the pain of violence. I was completely broken inside and getting pain attack every day anticipating what is waiting for me from him (husband). He beats me every day using vulgar words”

“Initially I did not tell anything but she (MHP) suspected of violence after seeing bruises and old scar marks on my face and neck…. hence I shared.”

Perceived postdisclosure feelings by women with intimate partner violence (includes voluntary disclosure)

The responses of the women about how did they feel/perceived after disclosing IPV to MHPs were generally positive. The most commonly used expressions were “I felt relaxed and relieved from pain and stress.” Others felt “embarrassed” or “ashamed” as they could do nothing to change their situation. Some women scared if the MHPs confront violence with their spouses what will happen to them and what would they tell them after going home. Few women got some information from MHPs about agencies available to protect them from IPV and felt good about the same.

“I felt ashamed of my own situation…(hummm)…I am helpless no nobody in my family is willing to help me.…….being born as a woman is curse”

“I did feel relieved (being asked the questions) and felt OK ………finally released the things I stomached it all these years without telling to any one (talk about abuse).

“I was actually scared because if he (husband) comes know after confronting with him…… then I am gone forever…(uhh)….he will beat me like anything after going home.”

“I felt relaxed and relieved from pain that I have been carrying all throughout my marriage.”

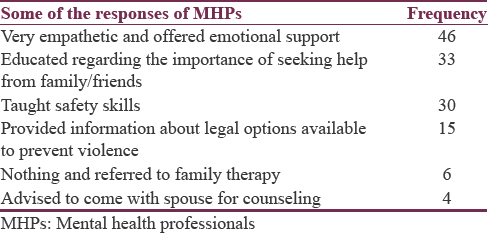

Mental health professionals’ response to disclosure of intimate partner violence perceived by women

Majority of the women perceived that MHPs responded to their disclosure of violence very empathetically, offered emotional support and taught them safety skills on how to protect themselves and their children from the abuse, and provided information about legal options and address of some domestic violence agencies [Table 2]. They made comments such as “She listened patiently to what I said,” “she was supportive and gentle,” “he allowed me to speak,” “told not to hide these issues and encouraged me to seek help from my parents/friends,” and “she instilled confidence in me.” Few women reported that MHPs did nothing following disclosure and referred them to family therapy unit for couple therapy. Others reported that they had been asked to bring their spouses for further counseling.

“She sat with me explained to me how I can protect myself during the violence.”

“She was very kind and gentle; and she was taking her time with me.”

“They told me to file a complaint in police station and provided contact details women's help line.”

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to look at the barriers to disclose IPV among female patients availing services at tertiary care mental health settings. Our main findings were women experiencing IPV were reluctant to disclose IPV because of their concerns about the potential consequences from the perpetrators. Women feared that if they disclosed violence to MHPs, the perpetrator might come to know this and they could be at an increased risk of violence or they would not be brought to regular follow-up consultation to psychiatric hospital. Nondisclosure can, therefore, be a very rational decision based on women's knowledge of the risks and benefits of disclosure. These findings are similar to those reported by women in health and nonmental settings.[910111213] Women also feared that they would not be believed if they disclosed abuse because MHPs would focus solely on their symptoms. We also found additional barriers to disclose IPV due to stigma associated with mental illness where women perceived that MHPs may question the credibility of their disclosure of domestic violence in light of their mental illness. Lack of privacy was another important barrier for nondisclosure where women reported that MHPs discussed the abuse in the presence of their violent partners. Such assessment can increase women's risk of abuse and encourage abusive partner to exercise further power over their partner in nontherapeutic environment. The finding of the current study is corroborated with several studies focusing on screening IPV which revealed that victims of violence would actually support the screening of violence under certain conditions: assurance of privacy, a nonjudgmental clinician, safety and support, assurance of confidentiality, and provision of a rationale for the purpose of the screen.[141516] The results for nondisclosure of violence underline the need for MHPs to make comprehensive assessments of the meaning, context, motivations, and situations surrounding abuse prior to the formulation of tailor-made individualized treatment plans. Women also expressed shame and embarrassment when asked about domestic violence and unsure of helping the role of MHPs. These findings reveal the importance of mandatory screening and offering individualized tailor-made psychosocial interventions to women experiencing IPV by MHPs in tertiary psychiatric care. MHPs should screen routinely for violence for every woman during their health-care visits and also provide sufficient information to women about making informed decisions about implications of disclosure of IPV and options available to them to prevent the violence. MHPs should also provide validating and nonjudgmental responses which address the issues of safety and available support options, ensuring women's autonomy in subsequent decisions.[117]

Limitations

The study was confined to one mental health setting, thus the generalizations of results may not be possible. However, the findings have implications for MHPs’ mandatory screening and documenting disclosure of violence and conducting risk assessment, safety planning, and discussing options in addressing the domestic violence with women in cessation of violence. There is a need to replicate the findings with larger population involving other health and mental health settings.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by intramural NIMHANS funding (NIMH/Proj-VMN/00559/2016-17).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- WHO. Responding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Against Women: WHO Clinical and Policy Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault and Stalking: Findings from the British Crime Survey. Home Office Research Study 276. 2004. London: Home Office; Available from: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs04/hors276.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of violence against women. In: Okpaku E, ed. Global Mental Health. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2002.

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3)-2005-2006. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2007.

- Global health. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 2013;340:1527-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women reporting intimate partner violence in India: Associations with PTSD and depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:203-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Domestic and sexual violence against patients with severe mental illness. Psychol Med. 2015;45:875-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Help-seeking amongst women survivors of domestic violence: A qualitative study of pathways towards formal and informal support. Health Expect. 2016;19:62-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women exposed to intimate partner violence: Expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:22-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intimate partner violence and help-seeking – a cross-sectional study of women in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:866.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to Help Seeking: Older Women's Experiences of Domestic Violence and Abuse Briefing Note, Monograph, University of Stanford Manchester. 2016. Available from: http://www.usir.salford.ac.uk/41328/

- [Google Scholar]

- Help seeking behaviours among survivors of intimate partner violence in India. Online J Ment Health Educ. 2016;1:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Universal screening for intimate partner violence: A systematic review. J Marital Fam Ther. 2011;37:355-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disclosing intimate partner violence to health care clinicians – What a difference the setting makes: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:229.

- [Google Scholar]

- The factors associated with disclosure of intimate partner abuse to clinicians. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:338-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of battered women in health care settings: A qualitative study. Women Health. 1996;24:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]