Translate this page into:

Cerebellar Liponeurocytoma: A Rare Fatty Tumor and its Literature Review

Address for correspondence: Dr. Arivazhagan Arimappamagan, Department of Neurosurgery, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Hosur Road, Bengaluru - 560 029, Karnataka, India. E-mail: arivazhagan.a@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Cerebellar liponeurocytoma is a rare oncological entity, and the knowledge about the treatment and outcome of these rare tumors is still evolving. Very few cases have been described in literature. We report a middle-aged male who presented with raised intracranial pressure features and gait ataxia. His imaging features revealed classical features of liponeurocytoma in cerebellar vermis, with abundant fat component evident in both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. He underwent resection of the lesion and has been asymptomatic for 4 years. This report describes the classical radiological and immunohistochemical features of this rare entity with favorable outcome and reviews the existing literature.

Keywords

Cerebellar liponeurocytoma

histopathology

magnetic resonance imaging

outcome

INTRODUCTION

Cerebellar liponeurocytoma is a rarely encountered tumor, reported first by Bechtel et al. (1978) in a 44-year-old male who named it “lipomatous medulloblastoma,” thus referring to its significantly better prognostic nature.[1] Since then, various authors have reported it using different names as follows: neurolipocytoma,[2] medullocytoma,[3] lipidized medulloblastoma,[4] and lipomatous glioneurocytoma.[5] Later, in the World Health Organization (2000) classification, it was denoted as a separate Grade I entity. However, due to multiple reported recurrences and atypical features, it was then upgraded to Grade II in the updated WHO classification of 2007.[67] We report a case of liponeurocytoma in a 55-year-old male with more than 4 years follow-up after surgery along with a literature review of previously reported cases.

CASE REPORT

Clinical presentation

A 55-year-old male presented with 5 months’ history of dull aching occipital headache associated with vomiting and visual blurring at the peak of headache. He also complained of inability to maintain balance while walking or standing. On examination, he had papilledema and tandem gait ataxia.

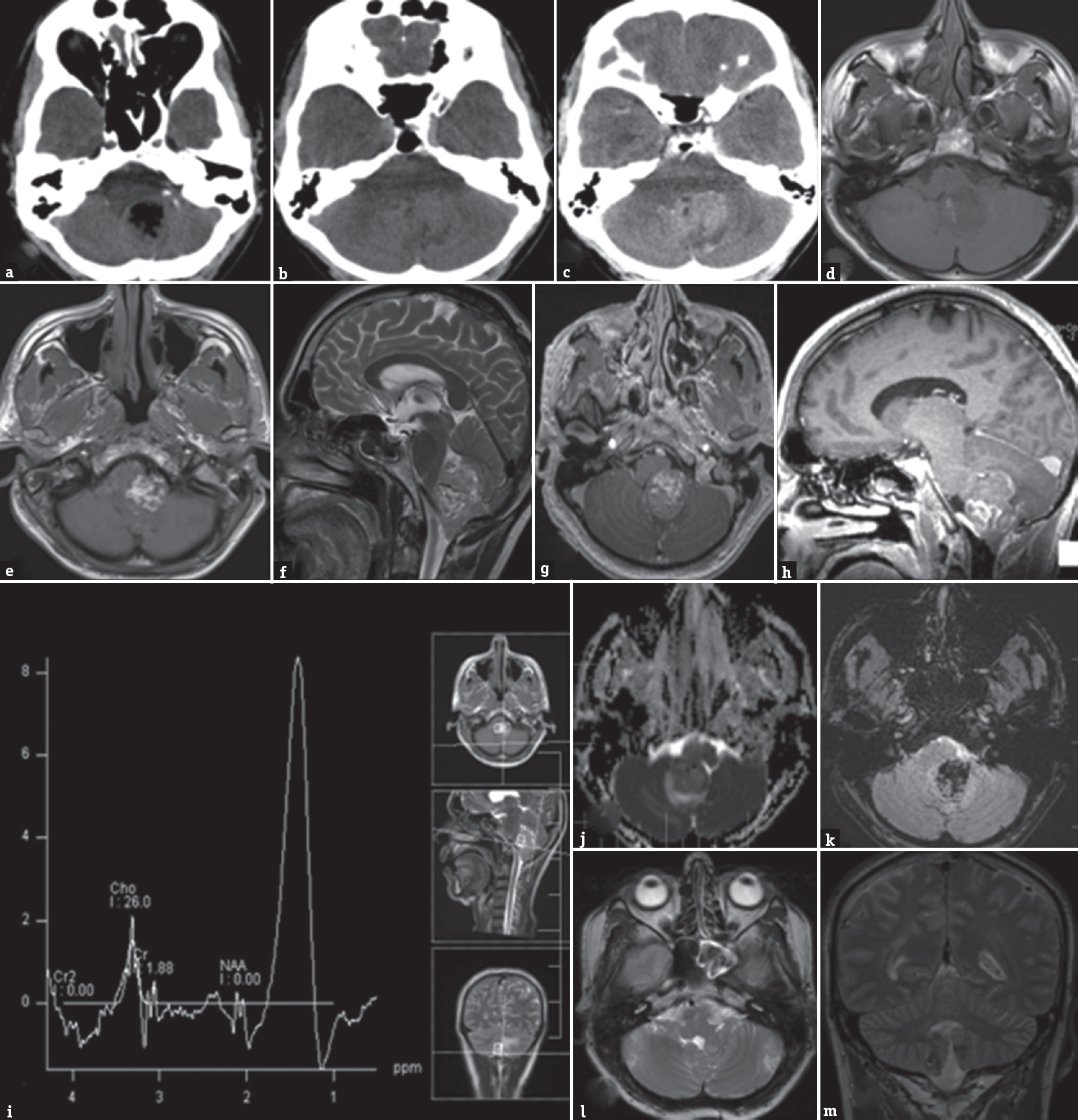

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain revealed a heterodense lesion in the 4th ventricle, with hypodense central component with mild hydrocephalus [Figure 1a-c]. MRI brain with contrast showed a lesion, measuring 3.9 cm × 3.1 cm × 4.5 cm, arising from the vermis of the cerebellum completely effacing the fourth ventricle, heterogenous on T1-weighted and T2-weighted imaging with patchy contrast enhancement with perilesional edema and obstructive hydrocephalus [Figure 1d-l].

- Computed tomography brain (a and b) plain and contrast-enhanced (c) images show a mass lesion in the posterior fossa, with hyperdense superior component, with moderate enhancement. The inferior component is hypodense, has Hounsfeld unit of-31, suggesting fat. Magnetic resonance imaging brain T1 axial images (d and e) showed heterointense lesion involving vermis and fourth ventricle, with hyperintense inferior component and isointense superior component, with similar signal changes in T2 sagittal images (f). Mild enhancement was noted with contrast (g and h). Few areas of restricted diffusion were noted (j). Gradient echo sequence showed abundant blooming of the hyperintense component, suggesting fat (k). MRS showed lipid peak in the region of 1.3 ppm (i). Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging brain 42 months after surgery showed a small asymptomatic residue in the vermis (l and m)

He underwent midline suboccipital craniectomy, C1 posterior arch excision, and near-total resection of the lesion. The tumor was soft, vascular with dense septae, adherent to the floor of the fourth ventricle thus necessitating a near-total resection. The patient had transient right VI cranial nerve palsy in the postoperative period, which resolved over 7 days.

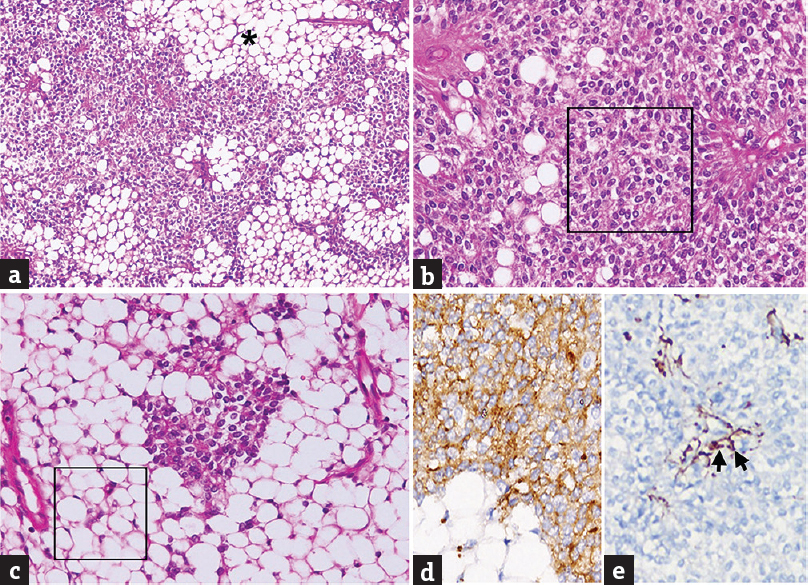

The resected tumor tissue revealed a moderately cellular tumor with variable morphology [Figure 2]. Large lobules of relatively rounded cells with clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm were separated partially by branching vessels. Focal perivascular arrangement by columnar cells was seen. The nuclei were medium sized, round, and vesicular. Focal areas showed hypercellularity and mild hyperchromasia and atypia. Admixed with the neurocytic component in several foci were large islands of mature adipocyte cells composed of cells with abundant clear cytoplasm. Areas of hemorrhage and focal choroid plexus infiltration were seen. On immunohistochemistry, the neurocytic tumor cells were strongly positive for synaptophysin indicating their neuronal lineage and negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein. The latter was only positive around blood vessels, bordering tumor lobules, and adipocyte aggregates highlighting the reactive astrocytes. EMA (epithelial membrane antigen) was negative. Immunostain for Ki-67 (MIB-1), a marker of proliferation, showed a nuclear labeling index of 4%–5%. A histological diagnosis of liponeurocytoma WHO Grade II was made [Figure 2].

- Liponeurocytoma. (a) Moderately cellular tumor composed of sheets of round cells, the neurocytes, interspersed with islands of mature adipose tissue (*). (b) Predominantly neurocytic area composed of relatively isomorphic cells with bland, round to oval, vesicular nuclei and moderate, clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm (square). (c) The lipomatous component is composed of mature adipocytes with abundant clear cytoplasm (square). (d and e) The neoplastic neurocytic cells are positive for synaptophysin (d) and negative for glial fibrillary acidic protein (e). A few perivascular reactive astrocytes are labeled (arrows) (a: H and E, ×100; B and c: H and E, ×200; d: Synaptophysin immunostain, ×400; e: glial fibrillary acidic protein immunostain, ×400)

The patient was advised regular follow-up. At 4 years’ follow-up, he is asymptomatic, and MRI brain showed a small residual lesion at the floor of the fourth ventricle without any mass effect or surrounding edema [Figure 1m and n].

DISCUSSION

Oudrhiri et al., in 2013, in his paper, reviewed 36 previously reported cases of liponeurocytoma and found that the average age of occurrence of this lesion was 49 years (range 32–79 years) with a female preponderance (1.8:1).[8] Recent reports also exist in the form of individual cases, the most common being in the infratentorial location.[910111213] Gembruch et al., in a systematic review of all the reported cases (n = 73) until 2018, noted that these tumors had low MIB-1 proliferation index (3.73 ± 4.01%).[14] Of the infratentorial location, the cerebellar hemisphere is the most common location.[151617] Intraspinal extension to C1–C2 space[1618] and one case of intraspinal lumbar metastasis which occurred 11 years after initial diagnosis has been reported.[15]

Central neurocytomas may be considered in differential diagnosis, though they usually do not possess lipomatous component. This fat in liponeurocytoma can be detected on CT as a hypodense lesion. MRI imaging will reveal a hyperintense lesion on T1-weighted images, which gets inverted in fat-suppressed images.[16] These findings, although not given attention initially, can be understood retrospectively after histological diagnosis. An awareness of this rare entity, a clear understanding of MR characteristics, and the presence of fat in the lesion will clinch the diagnosis preoperatively. These tumors should be differentiated from medulloblastoma and ependymoma, which can rarely demonstrate T1 hyperintensity.[16] Histologically, classic medulloblastoma can demonstrate foamy histiocytes along with primitive neuroectodermal cells. However, a high proliferative index will clearly indicate the malignant nature of tumor in medulloblastoma. As can probably be understood, differentiation between these entities is critical for decision-making.

In recent articles,[1011] a familial predisposition has been suggested with possibly an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. However, a causative genetic mutation as well the cell of origin of liponeurocytoma is yet to be ascertained. There are certain findings that have come to be associated with liponeurocytomas and their inheritance. A NEUROG1 transcript along with the absence of the ATOH1 transcript has been reported by Anghileri et al.[17] In the two samples of cerebellar liponeurocytoma, they also noted an overexpression of fatty acid-binding protein 4. These findings have led the authors to conclude that liponeurocytoma may be the consequence of a transformation of progenitor cells of the cerebellum to adipose tumor cells by possible aberrant differentiation. These are different from the cerebellar granular progenitor cells which were initially considered as the cell of origin for these tumors.[1719] Wolf et al. have suggested a germline mutation predisposing to the formation of liponeurocytomas.[11] Germline mutations are usually seen in a gene with a proven role in oncogenesis, and such an understanding would be beneficial to the other family members to ascertain their risk of tumor occurrence.

Optimum treatment modality, however, continues to be surgical. Considering the low proliferation index (<5%) reported by most authors, radiotherapy does not seem a pertinent option. Gembruch et al. reported that tumor recurrence was observed in 8.33% of cases after adjuvant radiotherapy. This was in stark contrast to the recurrence rates seen in cases that did not undergo radiotherapy (13/29 or 44.83%).[14] However, the indications of considering adjuvant therapy in an individual case are not clear, keeping in mind the benign nature of the tumor. A lack of knowledge of the tumor's natural history contributes to such lacunae in our understanding.

The management of recurrence needs to be patient specific with recurrent symptoms or significant growth of lesion requiring resurgery. Since the longest reported survival was 18 years in two patients,[1516] a slow growth rate can be assumed, and thus observation for “silent” recurrences is advocated. Thus, there is a need to report and follow-up these cases to better our understanding of this rare entity and to establish guidelines regarding treatment.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Mixed mesenchymal and neuroectodermal tumor of the cerebellum. Acta Neuropathol. 1978;41:261-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurocytoma/lipoma (neurolipocytoma) of the cerebellum. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1993;19:95-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medullocytoma (lipidized medulloblastoma). A cerebellar neoplasm of adults with favorable prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:656-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipomatous glioneurocytoma of the posterior fossa with divergent differentiation: Case report. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:639-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97-109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic and expression profiles of cerebellar liponeurocytomas. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:281-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding cerebellar liponeurocytomas: Case report and literature review. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2014;2014:186826.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does “cerebellar liponeurocytoma” always reflect an expected site? An unusual case with a review of the literature. Folia Neuropathol. 2014;52:101-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebellar liponeurocytoma in two siblings suggests a possible familial predisposition. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;32:154-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebellar liponeurocytoma: A rare intracranial tumor with possible familial predisposition. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial intracerebral cerebellar liponeurocytoma: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9556.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebellar liponeurocytoma – A rare entity: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liponeurocytoma: Systematic review of a rare entity. World Neurosurg 2018 pii: S1878-8750(18) 32021-7

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipomatous medulloblastoma in adults. A distinct clinicopathological entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:413-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroimaging of cerebellar liponeurocytoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:324-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- FABP4 is a candidate marker of cerebellar liponeurocytomas. J Neurooncol. 2012;108:513-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supratentorial and cerebellar liponeurocytomas: Report of four cases with review of literature. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:121-7.

- [Google Scholar]