Translate this page into:

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with rituximab treatment

*Corresponding author: Hiroshi Yokota, Department of Neurosurgery, National Hospital Organization Osaka Minami Medical Center, Kawachinagano, Osaka Japan. hyokota0001@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Yokota H, Hoshida Y, Watanabe K, Yamada T. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with rituximab treatment. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:396-8. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_434_2023

Dear Editor,

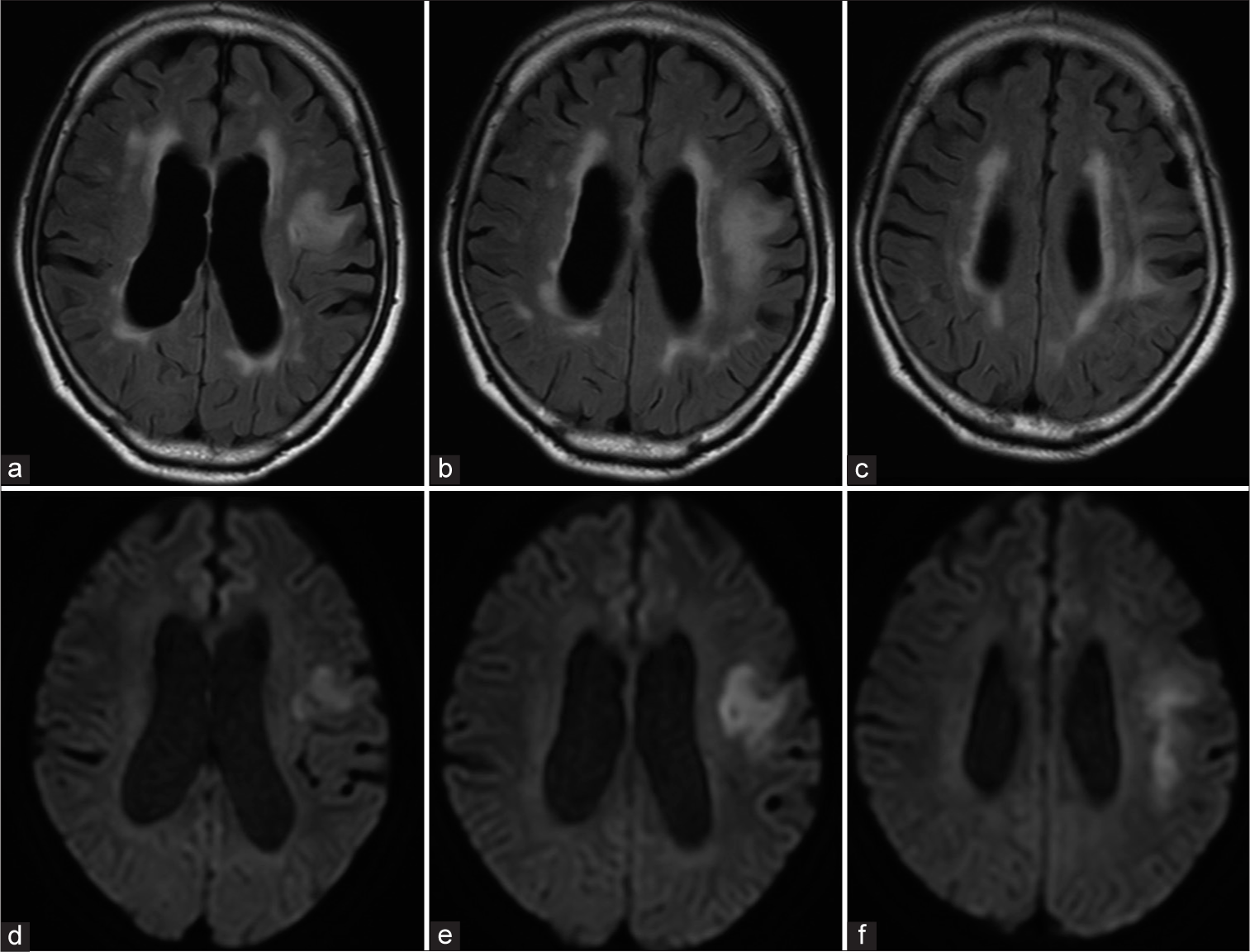

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a demyelinating disease caused by John cunningham virus (JCV) infection in the central nervous system. The potential risk of PML in patients, who receive treatment with rituximab, the first anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, is becoming increasingly recognized. A 67-year-old HIV-negative man presented with right-sided hemiparesis, dysarthria, and non-fluent aphasia. During 1-1/2 years following the diagnosis of primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the duodenum, the patient had received eight cycles of rituximab-based chemotherapy using rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, followed by four cycles of rituximab, mitoxantrone, etoposide, carboplatin, and prednisolone and three of rituximab, gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone. An MRI revealed fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion-weighted hyperintensity in frontal subcortical white matter [Figure 1], with T1-hypointense findings without gadolinium enhancement also noted. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained from a lumbar puncture revealed mild pleocytosis at 70 mg/ dL. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results showed JCV DNA to be undetectable in CSF. Furthermore, hepatitis B reactivation was indicated. A brain biopsy procedure for the left frontal lesion was performed, and histological examination results revealed severe demyelination and glial cells with swollen nuclei [Figure 2a]. Simian virus 40 (SV 40) protein-positive nuclei were also confirmed in glial cells [Figure 2b]. A definite diagnosis of PML associated with rituximab-based chemotherapy was made. The patient received supportive therapy and died four months later due to a systemic infection and pulmonary complications.

- (a-c) Magnetic resonance images with fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and (d-f) diffusion-weighted sequences showing hyperintensity in left frontal subcortical white matter.

![(a and b) Brain biopsy histopathological, and postmortem (c) brain and (d and e) histopathological findings. (a) Enlarged glial cell nuclei (arrows) can be seen in the background demyelination along with macrophage migration (hematoxylin and eosin [HE] staining, ×400). (b) Immunohistochemistry for the Simian virus 40 (SV 40) antigen showed positive findings for glial cell nucleoli (arrowheads) (SV 40 stain, ×200). (c) Postmortem image of coronal section of brain showing multiple foci with brownish pigmentation, predominantly in subcortical white matter. Regions encircled with blue lines indicate histologically proven demyelination lesions. (d) Gross findings of demyelination in subcortical white matter (right side of panel) (Kluver-Barrera staining, ×12.5). (e) Arrows show glial cells with eccentric enlarged nuclei in eosinophilic cytoplasm (HE staining, ×400).](/content/150/2024/15/2/img/JNRP-15-396-g002.png)

- (a and b) Brain biopsy histopathological, and postmortem (c) brain and (d and e) histopathological findings. (a) Enlarged glial cell nuclei (arrows) can be seen in the background demyelination along with macrophage migration (hematoxylin and eosin [HE] staining, ×400). (b) Immunohistochemistry for the Simian virus 40 (SV 40) antigen showed positive findings for glial cell nucleoli (arrowheads) (SV 40 stain, ×200). (c) Postmortem image of coronal section of brain showing multiple foci with brownish pigmentation, predominantly in subcortical white matter. Regions encircled with blue lines indicate histologically proven demyelination lesions. (d) Gross findings of demyelination in subcortical white matter (right side of panel) (Kluver-Barrera staining, ×12.5). (e) Arrows show glial cells with eccentric enlarged nuclei in eosinophilic cytoplasm (HE staining, ×400).

An autopsy was performed, which showed a brain weight of 1180 g. Multiple foci of ill-defined brownish patches in cortical and subcortical white matter were noted in a gross inspection of the cerebrum [Figure 2c], while histopathological findings revealed multiple foci related to severe demyelination [Figure 2d]. Characteristic histological findings of PML including glial cells with enlarged eccentric nuclei in the eosinophilic cytoplasm along with foamy macrophage invasion were also confirmed [Figure 2e], with those findings extending to the brain stem and cerebellum. A PCR examination of post-mortem brain tissue obtained from the left frontal lesions revealed positive for JCV DNA at 3.17 × 106 copy numbers/μg. Residual lymphoma cells were not found, though subtle mature lymphocyte infiltration was noted in the duodenum.

Since the first report of potential risk of PML in association with rituximab presented in 2002 that has been increasingly recognized in a subset of rituximab-treated patients with the risk of PML development, estimated to be five times greater as compared to those not treated with the drug.[1] Although histopathological results based on brain biopsy findings are required for a definitive diagnosis along with confirmation of JCV, more cases have been diagnosed using CSF JCV PCR results.[2] Nevertheless, a brain biopsy is required for clinically suspected PML cases when those results are negative. The typical histopathological triad includes multifocal demyelination, enlarged bizarre astrocytes, and hyperchromatic enlarged oligodendroglial nuclei with dot-shaped intranuclear inclusions generally observed in enlarged oligodendroglial cells.[3] Immunohistochemistry with JCV capsid protein (VP-1), a major structural protein, is a specific and sensitive method to confirm the presence of the virus[4] while SV 40 protein positivity found in the nuclei of abnormal glial cells indicates cross reactivity. A PCR assay to detect JCV in brain tissue is also available as an alternative. Autopsy results of cases of PML associated with rituximab treatments for non-Hodgkin lymphoma have rarely been reported,[4,5] though in addition to providing detailed histopathological findings, Sano, et al. investigated the concentration of mefloquine, used as a treatment for PML associated with rituximab, in postmortem brain tissue.[5]

Additional studies that include autopsy reports are needed to clarify the pathogenesis of patients with PML associated with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Hospital Organization Osaka Minami Medical Center, number R4-59, dated November 21, 2022.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab: A 20-year review from the Southern Network on Adverse Reactions. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e593-604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PML diagnostic criteria: Consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80:1430-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Dot-shaped inclusions and virus-host interactions. Neuropathology. 2015;35:487-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An autopsy case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after rituximab therapy for malignant lymphoma. Neuropathology. 2019;39:58-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy derived from non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Neuropathological findings and results of mefloquine treatment. Intern Med. 2015;54:965-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]