Translate this page into:

Trans-ciliary minimally invasive keyhole craniotomy for skull base and vascular lesions

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Conventional approaches to the anterior and lateral skull base would necessarily include a large craniotomy and possibly an orbitozygomatic osteotomy.[12] Approach-related complications include visible scars, increased blood loss during surgery, facial and orbital ecchymosis, and long-term problems such as temporalis muscle atrophy and painful jaw opening.[2] Many skull base lesions can be easily accessed via a minimally invasive keyhole craniotomy using an eyebrow incision. This approach is effective in minimizing surgical trauma, hospital stay, and long-term morbidity.[34]

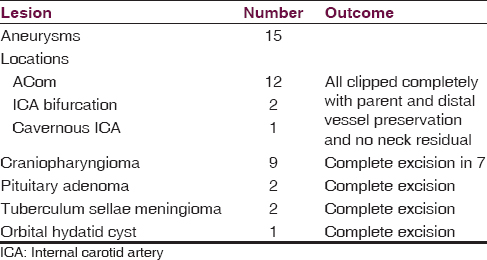

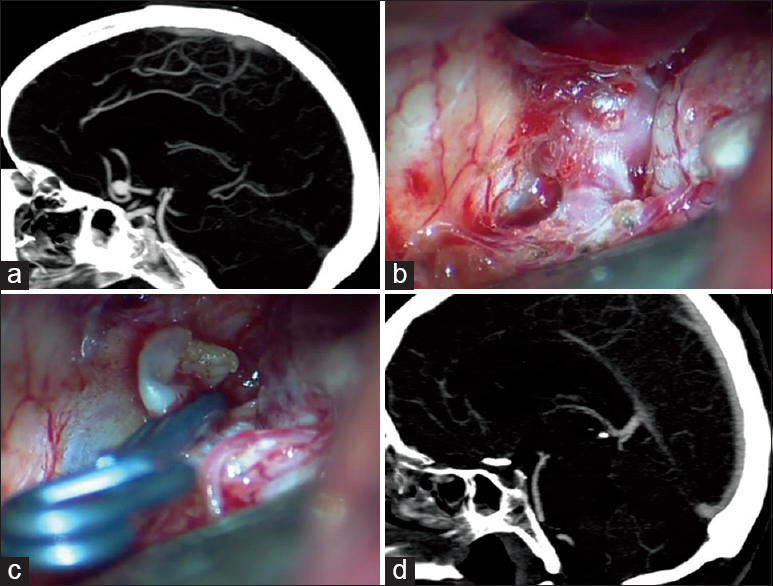

We reviewed the records of all patients operated via the supra-brow approach over the past 5 years in our center. A total of 29 patients had been operated via this approach. Their ages ranged between 1 and 64 years; there were 19 adults and 10 children; 17 patients were males. Fifteen patients were operated for aneurysms and 14 patients for other lesions [Table 1].

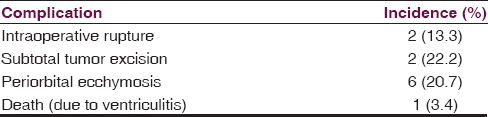

All except one giant cavernous segment aneurysm presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage. All patients were operated in the early postrupture period (<5 days); the subarachnoid space was thus filled with dense clots in all instances [Figure 1]. We did not, however, have to use lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage in any of the cases. Intraoperative rupture occurred in 2 cases; the bleeding could be controlled by rapid temporary clipping of the parent vessel in both instances. In the tumor group, gross total excision could be achieved in 12 of the 14 patients [Figure 2]. In 2 patients with craniopharyngioma, tumor residue was left due to dense adhesions to the optic chiasm and hypothalamus. Both these patients received imaging-guided radiotherapy subsequently.

- An ACom artery aneurysm. (a) The preoperative computed tomography (CT) angiogram (sagittal view) showing the aneurysm fundus projecting anteriorly. (b) Intra-operative view of the aneurysm. (c) Clip applied across the neck. (d) Postoperative CT angiogram showing no residual fundus

- Preoperative and postoperative images of a giant craniopharyngioma excised via the mini-frontal supra-brow craniotomy

The duration of the surgical procedures varied between 1.5 and 3.5 h (1 h < the conventional procedures at our center). The average blood loss was <250 ml and none of the patients received a blood transfusion.

All patients tolerated the procedure well and required analgesics for a maximum of 5 days. None of them had any difficulties in chewing or swallowing. Six patients had periorbital ecchymosis which resolved in 5–7 days [Table 2]. The scar of the operative incision was inconspicuous at 6 weeks follow-up. Four patients in this group had a receding hairline with partial baldness, and the cosmetic outcome was especially good in them [Figure 3]. The wound healed well in children as well, and there was no loss of hair on the eyebrow [Figure 4].

- Patients with partial baldness. The conventional pterional incision would have left a disfiguring scar. The supra-brow incision is barely visible.

- A 1-year-old child operated for craniopharyngioma; the incision has healed well

The application of keyhole approaches depends on an exact knowledge of neuroanatomy. The introduction of long bayonetted instruments has made minimal access surgery safe.[34] There is a definite learning curve to implement these approaches.[5] The addition of an endoscope can provide a “third eye,” permitting the surgeon to peer into blind crevices not visualized through the microscope.

The mini-frontal keyhole craniotomy via a supra-brow incision should become a standard part of a neurosurgeon's armamentarium to tackle skull base lesions.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

References

- Surgical approaches to suprasellar and parasellar tumors. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:109-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The supraorbital keyhole approach to supratentorial aneurysms: Concept and technique. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:481-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lateral supraorbital approach as an alternative to the classical pterional approach. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;94:17-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsurgical experience with keyhole operations on intracranial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2006;66(Suppl 1):S2-9.

- [Google Scholar]