Translate this page into:

Teaching Glasgow Coma Scale Assessment by Videos: A Prospective Interventional Study among Surgical Residents

Jitin Bajaj, MCh Department of Neurosurgery, NSCB Medical College Jabalpur, 482003 India bajaj.jitin@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Objective Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) assessment is vital for the management of various neurological, neurosurgical, and critical care disorders. Learning GCS scoring needs good training and practice. Due to limitation of teachers, the new entrants of the clinical team find it difficult to learn and use it correctly. Training through videos is being increasingly utilized in the medical field. This study aimed to evaluate the efficiency of video teaching of GCS scoring among general surgery residents.

Materials and Methods A prospective study was done utilizing the freely available video at glasgowcomascale.org. The participants (general surgery residents, 1st–3rd year) were asked to assess and record their responses related to GCS both before and after watching the video. A blinded neurosurgeon recorded the correct responses separately.

Statistical Analysis The difference between correct responses of the residents before and after watching the video was calculated using the “chi-square test.” p-Value ≤ 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results There was a significant improvement in GCS scoring by residents after watching the videos (p < 0.05). On estimating the responses separately, all the three responses (eye, verbal, and motor) improved significantly for 1st-year residents while only the motor response improved significantly for 2nd- and 3rd-year residents. The mode subjective improvement for the 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-year residents was 5, 4, and 3, respectively.

Conclusion Training GCS scoring through videos is an effective way of teaching the surgery residents with maximum benefit to the junior-most ones.

Keywords

education

Glasgow Coma Scale

neurology

neurosurgery

traumatic brain injury

unconsciousness

Introduction

Brain damage is a major cause of morbidity and mortality after trauma.1 2 Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) assessment is an important aspect in neurological assessment and its management.3 4 5 It helps in the objective assessment of the patients and facilitates accurate interpersonal communication. GCS fluctuation is important to pick up at the earliest, as it may change the treatment options. Learning GCS assessment is important for neurosurgeons, neurologists, allied surgical disciplines, nurses, and paramedics involved in pre- to posthospital care of patients. GCS is a part of the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons score for subarachnoid hemorrhage6 and Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II score,7 and therefore useful for every intensivist.

Training and education is important for reliability of the GCS scoring.8 Though the GCS assessment is taught during the undergraduate medical training, the postgraduates and practicing physicians often miscalculate the GCS score.9 It takes not only time and practice to master the GCS assessment, but also a certified trainer/doctor to teach it. The trained teachers are less in number and have limited time for every new member of their team and junior staff. This makes the learning of this score difficult for the new members. Learning through videos has been shown beneficial in many studies.10 11 There are several free videos available on “YouTube” and other Web sites to learn the GCS assessment. One of the prominent ones is available at glasgowcomascale.org,12 which is promoted by Prof. Graham Teasdale himself, the creator of GCS.3

Beneficial effect of instructional videos to learn GCS has been shown; however, an improvement, if any, in individual GCS score components assessment has not been studied.13 This prompted us to assess the effectiveness of the video teaching method for GCS score, including its components, for the general surgery residents.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in the Department of Surgery and Neurosurgery in a tertiary referral center. It was a prospective interventional study to train the general surgery residents for GCS scoring. Ethical clearance was taken from the institutional ethics committee, and the trial was registered in the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2019/10/021545).

Each surgery resident was asked to assess the GCS score of three brain trauma patients. The residents were assigned based on their alphabetical order. They were then shown a certified GCS assessment video from glasgowcomascale.org as a one-on-one session. The video was played as many a time the resident wanted. Later, they were again asked to assess the GCS of the same patients. The correct response was objectively recorded by the blinded consultant neurosurgeon, and based on his responses the evaluation was done. The confidence interval was taken as 95%. The participants were also asked to grade the benefit they got from the videos, on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (1 = no benefit, 5 = maximum benefit possible). The results were analyzed for all residents and for each year of residents separately.

Inclusion criteria were adult head trauma patients from GCS 3 to 15, whose relatives agreed to take part in the study. The participants were general surgery residents (1st–3rd year). These residents did not have any didactic teaching of the GCS scoring; however, the 2nd- and 3rd-year residents had a neurosurgery rotatory posting of 1 month each. Exclusion criteria were pediatric head injury and vitally unstable patients.

Statistical Analysis

The data were collected in an Excel sheet, and was analyzed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, United States). The difference between correct responses of the residents before and after watching the video was calculated using the “chi-square test.” p-Value ≤ 0.05 was taken as significant. Sample size was calculated using the data of Lane et al study, where they found that the post-video correct responses increased from 14.7 to 64%.13 The sample size came to be 14 for each arm.

Results

There were 75 responses (75 before and 75 after watching the videos) from the 25 participant residents for 25 patients. There were 39 1st-year, 21 2nd-year, and 15 3rd-year residents’ responses. In our study, the eye responses ranged from 1 to 4, verbal responses from 1 to 5 (including t for intubated/tracheostomized), and motor responses from 3 to 6. There were 12% (n = 9) severe, 64% (n = 48) moderate, and 24% (n = 18) mild head injuries according to the GCS scoring.

Eye Response

The pre-video eye response ranged from 1 to 5 (score 5 wrongly entered by one resident). The correct pre-video eye responses were 58.7% (n = 44). Post-video the correct eye responses improved (p < 0.02) to 88% (n = 66).

Verbal Response

The pre-video verbal response ranged from 1 to 6; including t response (one resident wrongly entered 6). The correct pre-video verbal responses were 69.3% (n = 52), while post-video correct responses improved (p = 0.001) to 92% (n = 69).

Motor Response

The pre-video motor response ranged from 1 to 7 (score 7 being wrongly entered by one resident). The correct pre-video motor responses were 52% (n = 39), while post-video correct responses improved (p < 0.001) to 84% (n = 63).

The year-wise difference between the residents for eye, verbal, and motor responses is shown in Table 1. For 1st-year residents, there was a significant improvement in assessment for all three responses: eye (p < 0.001), verbal (p < 0.001), and motor responses (p = 0.001). For 2nd- and 3rd-year residents, the motor response significantly improved (p < 0.05) after the video learning, while there was no improvement (p = NS) for eye and verbal response assessments.

|

Year |

Total responses |

GCS component |

Correct count |

Correct percentage |

p-Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-video |

Post-video |

Pre-video |

Post-video |

||||

|

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; NS, not significant. |

|||||||

|

1st |

39 |

Eye |

14 |

35 |

35.9 |

89.7 |

0.000 |

|

39 |

Verbal |

19 |

36 |

48.7 |

92.3 |

0.000 |

|

|

39 |

Motor |

24 |

34 |

61.5 |

87.2 |

0.001 |

|

|

2nd |

21 |

Eye |

15 |

16 |

71.4 |

76.2 |

NS |

|

21 |

Verbal |

21 |

21 |

100 |

100 |

NS |

|

|

21 |

Motor |

9 |

17 |

42.9 |

81.0 |

0.002 |

|

|

3rd |

15 |

Eye |

15 |

15 |

100 |

100 |

NS |

|

15 |

Verbal |

12 |

12 |

80 |

80 |

NS |

|

|

15 |

Motor |

6 |

12 |

40 |

80 |

0.009 |

|

Subjective Satisfaction

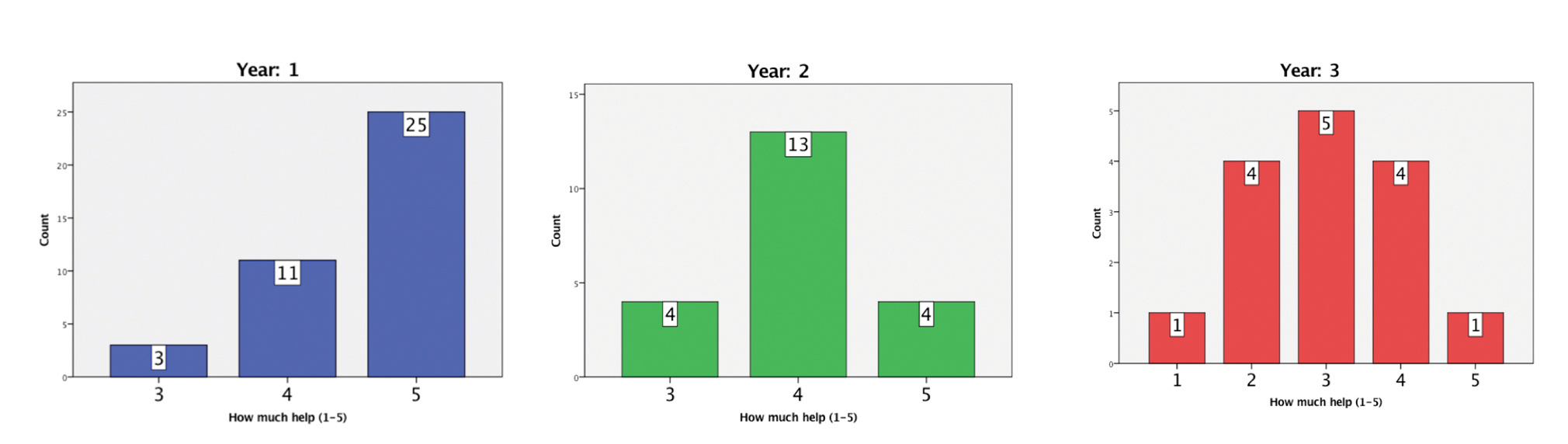

Maximum residents rated 4 or 5. On deducing the year-wise data for the residents, the mode responses for 1st-year residents were 5, 2nd-year residents were 4, and 3rd-year residents were 3. The residents’ year-wise responses have been shown in Fig. 1.

-

Fig. 1 Subjective year-wise satisfaction of the residents on a Likert scale of 1 to 5.

Fig. 1 Subjective year-wise satisfaction of the residents on a Likert scale of 1 to 5.

Discussion

Learning through audio-visual aids is better than reading or hearing a lecture.14 15 The GCS has stood the test of time, and its knowledge is important for surgery residents.16 Our study was a prospective analysis of the responses of learning GCS through videos for general surgery residents, before and after watching it. The method, though helpful for all the residents, was most helpful for the junior-most participants. There was a significant difference in all three responses of GCS for 1st-year residents, and for the motor response in 2nd- and 3rd-year residents (p < 0.05). This may be because the 2nd- and 3rd-year residents already had a prior basic knowledge during their short neurosurgical rotatory training. The eye and verbal responses have fewer points, compared with the motor one, and therefore have fewer chances of fault. Recording of eye and verbal responses are simple and require lesser neurological skills compared with the motor one. The motor component improved for all the residents. Several studies have identified the motor score to be the best predictor of the outcome.17 18 Thus, the videos could make a significant difference in learning GCS for the residents, irrespective of their previous training.

Due to the busy schedule of neurologists and neurosurgeons, there is always less time for didactic and one-on-one clinical teaching. Any new learning is a process and takes time and practice to master, and GCS scoring is also one of them. Using reliable, freely available videos, a new member of the team can see and learn. Although none of the groups reached to 100% accuracy after watching the videos, all of them improved to a significant level.

It is well known that any learning can be short lasting. A recorded video can be viewed multiple times and whenever desired. Also, when the video shows examples over patients (real or dummy), it becomes easy to understand, and visual memory helps it to be retained.14 15

Advantages of learning via audio-visual aids have been known since Dale’s landmark publication and its widely quoted “cone of experience” (later known as “Learning Pyramid”).19 Although the degree of quantitative improvement by video teaching has been queried by few subsequent authors, its advantages have been endorsed by one and all.15 20

Lane et al showed an improvement in GCS scoring from 14.7 to 64% for emergency medical services providers through the video method, but the individual components of GCS were not assessed.13 Feldman et al showed the effectiveness of GCS scoring aids.21 With videos, our study too could not achieve 100% accuracy for the participants. We feel the traditional person-to-person teaching and demonstration is and will remain a gold standard for learning GCS. However, to attain a certain level of basic training, GCS can be learned through videos. Our findings are in consonance with the recommendations of systematic review on the subject of factors influencing the reliability of the GCS.8

Limitations of our study include small number of participants. However, we had a variable group of participants, from junior-most to final year with varied learning, all of them showing improvement in the most important aspect of GCS scoring, that is, motor component. The study did not include the nurses and paramedical staff, and therefore cannot be generalized. A future study should include assessment in other health care providers also. The post-video responses were taken immediately after watching the videos. Thus, one cannot ascertain whether there will be any long-lasting learning through videos. However, one can view the video clip multiple times and can memorize it. The video was only for adults, and therefore the generalizability to the pediatric population cannot be made. A future trial for pediatric patients can also be done.

Conclusion

Training through videos is an effective way of teaching GCS scoring. Conceptualizing and learning how to grade GCS can improve for resident trainees. Motor response learning can be improved for all general surgery residents, while the most benefit accrued to the junior-most trainees.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by institute ethics committee IEC/2019/6379.

Authors’ Contributions

J.B. contributed in manuscript writing, data collection, and data analysis; S.R. in data collection and writing of the manuscript; V. P. in study designing and writing of the manuscript; P. A. in manuscript editing, study supervision, and data analysis; Y. Y. in study designing, study supervision, manuscript editing, and administrative support; and D. S. in study designing, study supervision, manuscript editing, and administrative support.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- Epidemiology of traumatic brain injuries: Indian scenario. Neurol Res. 2002;24(1):24-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological study of traumatic brain injury cases in a trauma centre of New Delhi (India) J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2015;8(3):131-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81-84. (7872)

- [Google Scholar]

- Predicting outcome in individual patients after severe head injury. Lancet. 1976;1:1031-1034. (7968)

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of a reliable admission Glasgow Coma Scale score for determining the need for evacuation of posttraumatic subdural hematomas: a prospective study of 65 patients. J Trauma. 1998;44(5):868-873.

- [Google Scholar]

- The World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale for subarachnoid haemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2003;59(3):236-237, discussion 237–238.

- [Google Scholar]

- APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818-829.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing the reliability of the Glasgow Coma Scale: a systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(6):829-839.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians’ knowledge of the Glasgow Coma Scale in a Nigerian University hospital: is the simple GCS still too complex? Front Neurol. 2012;3:28.

- [Google Scholar]

- YouTube videos as a teaching tool and patient resource for infantile spasms. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(7):804-809.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cinemeducation: teaching family systems through the movies. Fam Syst Health. 2000;18(4):455-466.

- [Google Scholar]

- GCS. The Glasgow structured approach to assessment of the Glasgow Coma Scale. glasgowcomascale.org

- Effectiveness of a Glasgow Coma Scale instructional video for EMS providers. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2002;17(3):142-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact on the level of anxiety and pain of the training before operation given to adult patients. Surg Sci. 2011;2(6):720-726.

- [Google Scholar]

- Edgar Dale’s Pyramid of Learning in medical education: a literature review. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1584-e1593.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Glasgow Coma Scale at 40 years: standing the test of time. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):844-854.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving the Glasgow Coma Scale score: motor score alone is a better predictor. J Trauma. 2003;54(4):671-678, discussion 678–680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing model performance for survival prediction using total Glasgow Coma Scale and its components in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(1):17-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- 1954. Audio-Visual Methods in Teaching. Rev. ed. New York: Dryden Press

- The Learning Pyramid: does it point teachers in the right direction? Education. 2007;128(1):64-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized controlled trial of a scoring aid to improve Glasgow Coma Scale scoring by emergency medical services providers. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(3):325-329.e2.

- [Google Scholar]