Translate this page into:

Recommendations of the Colombian Consensus Committee for the Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in Prehospital, Emergency Department, Surgery, and Intensive Care (Beyond One Option for Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Stratified Protocol [BOOTStraP])

Andres M. Rubiano, MD, PhD Department of Neurosciences and Neurosurgery, El Bosque University, Bogotá, Colombia; Medical and Research Director MEDITECH Foundation, MEDITECH Foundation Calle 7-A # 44-95, Cali, Valle Colombia andresrubiano@aol.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a global public health problem. In Colombia, it is estimated that 70% of deaths from violence and 90% of deaths from road traffic accidents are TBI related. In the year 2014, the Ministry of Health of Colombia funded the development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with severe TBI. A critical barrier to the widespread implementation was identified—that is, the lack of a specific protocol that spans various levels of resources and complexity across the four treatment phases. The objective of this article is to present the process and recommendations for the management of patients with TBI in various resource environments, across the treatment phases of prehospital care, emergency department (ED), surgery, and intensive care unit.

Methods Using the Delphi methodology, a consensus of 20 experts in emergency medicine, neurosurgery, prehospital care, and intensive care nationwide developed recommendations based on 13 questions for the management of patients with TBI in Colombia.

Discussion It is estimated that 80% of the global population live in developing economies where access to resources required for optimum treatment is limited. There is limitation for applications of CPGs recommendations in areas where there is low availability or absence of resources for integral care. Development of mixed methods consensus, including evidence review and expertise points of good clinical practices can fill gaps in application of CPGs. BOOTStraP (Beyond One Option for Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Stratified Protocol) is intended to be a practical handbook for care providers to use to treat TBI patients with whatever resources are available.

Results Stratification of recommendations for interventions according to the availability of the resources on different stages of integral care is a proposed method for filling gaps in actual evidence, to organize a better strategy for interventions in different real-life scenarios. We develop 10 algorithms of management for building TBI protocols based on expert consensus to articulate treatment options in prehospital care, EDs, neurological surgery, and intensive care, independent of the level of availability of resources for care.

Keywords

traumatic brain injuries

intensive care

emergency care

prehospital care

critical care

intensive care

Colombia

guideline

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a global public health problem.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by the year 2020, TBI will be one of the leading causes of death and disability globally.1 Approximately 1,250,000 people die each year as a result of road traffic accidents (RTAs).1 2 TBIs affect more than 10,000,000 people annually and are the leading cause of death among persons between 15 and 29 years of age.1 2

Epidemiological studies show regional variations, with higher mortality in patients from rural areas and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), in comparison with urban areas of high-income countries (HICs).3 4 This higher mortality and disability associated with TBI in the areas of lower income groups are associated with the lack of prevention, less control of risk factors, and lower capacity for acute care and rehabilitation.5 The WHO Global Report of Road Safety for the year 2015 states that 90% of deaths from RTAs occurs in LMICs.6 However, while LMICs account for 82% of the world’s population, only 54% of the world’s registered vehicles are in LMICs, indicating a disproportionate number of road traffic deaths.6 Colombia is a country that still maintains a high incidence of trauma from social violence and traffic accidents.7 Of these traumas, the estimates associated with TBI range from 49 to 70%.7 There is little accurate information in Colombia about the deaths attributed to TBI. However, estimates from autopsy reports of the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences indicate that 70% of deaths from violence and 90% of deaths from RTAs are TBI related.7

In the year 2014, the Ministry of Health of Colombia, through the convocation 563-2012 of the Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Information (COLCIENCIAS), funded the development of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients (older than 15 years) with severe TBI.8 This guideline was developed under the direction of the Meditech Foundation, utilizing expert clinical representatives from multiple disciplines involved in the comprehensive care of TBI patients. The document, including recommendations based on scientific evidence, is intended to decrease the heterogeneity in the management of these patients across the four treatment phases of prehospital care, emergency department (ED) management, surgery, and intensive care unit (ICU) (please refer http://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/gpc_sites/Repositorio/Conv_563/GPC_trauma_craneo/CPG_TBI_professionals.pdf ). Two years after its publication as a technical paper of the Ministry of Health, there were various meetings to advance implementation. During this process, an essential barrier to the widespread implementation was identified—that is, the lack of a specific protocol that spans various levels of resources and complexity across the four treatment phases.

Based on the current required regulations for enabling health services in Colombia, where complexity levels are described as shown in Table 1, a consensus process involving clinical experts was conducted to develop a series of management protocols to articulate treatment options for TBI specific to different levels of resources and complexity across the prehospital, emergency care, neurological surgery, and intensive care phases. The expert panel included representatives from the Colombian Association of Universities with programs in Prehospital Care, the Colombian Association of Specialists in Emergency Medicine, the Colombian Association of Neurosurgery, Chapter of Neurotrauma, and the Colombian Association of Critical Care Medicine and Intensive Care through the Chapter of Neurointensive Care. The objective of this article is to present the process and recommendations for the management of patients with TBI in various resource environments, across the treatment phases of prehospital care, ED, neurosurgery (NSG), and ICU.

|

Level of resource definitions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ambulances |

Emergency room |

Neurological surgery |

ICU |

||||

|

Basic emergency transport |

Advanced emergency transport |

Basic health facility (without CT) Low complexity |

Advanced health facility (with CT) Medium–high complexity |

Operation room with CT access but without neurosurgery |

Operation room with neurosurgery, but without ICU availability |

ICU with CT, center of medium complexity |

ICU with CT, in a center of medium–high complexity |

|

Abbreviations: AED, automated external defibrillator; CC, critical care; CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit. Source of Definitions: Colombian Ministry of Health Technical Documents and World Health Organization Technical Documents.9 10 |

|||||||

|

‒Vehicle with first responder (with or without training) ‒Vehicle with or without electronic monitoring of vital signs ‒Vehicle without advanced airway management equipment ‒Vehicle with or without IV fluids capability |

Vehicle with: ‒Physician, nurse, technician, or technical EMS support ‒Driver with training in basic life support ‒Mechanical ventilator with battery for at least 4 h ‒Electronic monitoring of vital signs ‒AED ‒Advanced airway management kit ‒Medications for advanced life support |

Facility with: ‒General physician with advanced life support training ‒Nurse or technician with basic life support training ‒Electronic monitoring of vital signs ‒AED ‒Cardiac arrest kit ‒Oxygen ‒Drug infusion pumps ‒Airway suction system ‒Advanced airway management kit ‒Basic radiology without CT ‒Availability of crystalloids fluids ‒Pharmacological support ‒Basic clinical laboratory |

Facility with: ‒General physician, emergency specialist, or family physician ‒Specialist availability in basic consultancy (general surgery/internal medicine/pediatrics) ‒Clinical laboratory ‒Radiology service (with CT) ‒Pharmacy ‒Respiratory therapy ‒Blood transfusion kit ‒Health care transport ‒Operating room with anesthesiology available |

Facility with: ‒General surgeon ‒Anesthesiologist ‒Operative room available ‒Surgical instrumentation ‒Surgical nurses ‒Clinical laboratory ‒Pharmacy ‒Basic surgical equipment ‒Facility without neurosurgery availability |

Facility with: ‒Anesthesiologist ‒Operative room available ‒Surgical instrumentation ‒Surgical nurses ‒Clinical laboratory ‒Pharmacy ‒Neurosurgery specialist ‒Advanced surgical equipment ‒No ICU capabilities |

Unit with: ‒Respiratory therapy ‒Electronic monitoring of vital signs ‒Cardiac arrest kit ‒Advanced airway equipment ‒Advanced drug management for pain and vasoactive drugs ‒Special unit for critical patients with or without CC physician. If there is not CC specialist available, a general physician with ICU nurses or nurse technicians is available. |

Unit with: ‒CC physician ‒Nurse with CC training ‒Respiratory therapy ‒Mechanical ventilator ‒Cardiac arrest Kit ‒Advanced airway management kit ‒Advanced medication availability ‒Electronic monitoring of vital signs ‒Neurosurgery consultant availability ‒CT, magnetic resonance imaging ‒Full specialist availability for consultation |

Materials and Methods

In March 2017, a national consensus conference for the development of the protocol for comprehensive care of adults with TBI was held in Bogota, Colombia. Twenty experts in prehospital care, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and intensive care attended, accompanied by five methodologists. Six participants attended through videoconferencing and 19 in person. The process took 3 days; 2 meeting days with 1 final consensus day during which participants discussed possible answers to the following questions.

|

Medication |

Option 1 |

Option 2 |

Option 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: Select any option for each one of the categories according to the availability of medications. |

|||

|

Inductors |

Ketamine Amp × 500 mg Dose: 1.5–2 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg: 105–140 mg |

Midazolam Amp × 5 mg/amp × 15 mg Dose: 0.1–0.3 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg: 7–21 mg |

Etomidate Amp × 20 mg Dose: 0.3 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 21 mg |

|

Muscular blockers |

Succinylcholine Amp × 250 mg Dose: 1–2 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 70–140 mg |

Rocuronium Amp × 50 mg Dose: 0.7–1 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 50–70 mg |

Vecuronium Amp × 50 mg Dose: 0.1 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 7 mg |

|

Analgesics |

Fentanyl Amp × 500 μg Dose: 2–4 μg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 140–280 μg |

Ketamine Amp × 500 mg Dose: 1.5–2 mg/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 105–140 mg |

|

|

Abbreviations: HTS, hypertonic saline; NS, normal saline; SBP, systolic blood pressure. |

||

|

Hypertonic fluids |

HTS 3% Peripheral vein |

HTS 7.5% Peripheral vein |

|

NS (0.9%) 400 mL + sodium chloride ampoules 100 mL (ampoules of 20 mEq in 10 mL) |

NS (0.9%) 100 mL + sodium chloride ampoules 150 mL (ampoules of 20 mEq in 10 mL) |

|

|

Dose: 3–4 mL/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 210–280 mL per dose Only for use if SBP < 100 mm Hg or clinical signs of brain herniation |

Dose: 2 mL/kg For a patient of 70 kg = 140 mL per dose Only for use if SBP < 100 mm Hg or clinical signs of brain herniation |

|

Prehospital Care

What is the best protocol (step by step) for treating an adult patient:

1. Mild TBI in a basic ambulance or basic emergency transport (BET)?

2. Moderate–severe TBI in a BET?

3. Mild TBI in a medical ambulance or advanced emergency transport (AET)?

4. Moderate–severe TBI in an AET?

Emergency Care

What is the best protocol (step by step) for managing an adult patient with:

5. Mild TBI in a low complexity ED without computed tomography (CT)?

6. Mild TBI in a medium–high complexity ED with CT?

7. Moderate–severe TBI in a low complexity ED without CT?

8. Moderate–severe TBI in a medium–high complexity ED with CT?

Neurological Surgery

9. What is the best protocol to determine if a patient with TBI requires immediate neurological surgery?

What is the best protocol to manage a patient who requires immediate surgery in a medical center that:

10. Does it not have neurosurgery?

11. Does it not have neurosurgery?

Have neurosurgery but no ICU?

Intensive Care

12. What is the best protocol to manage a patient with moderate–severe TBI in an intermediate care unit (no ICU) within a center of medium complexity?

13. What is the best protocol to manage a patient with moderate–severe TBI in an ICU within a center of medium–high complexity?

We conducted a systematic search for publications that described methods for conducting consensus processes when evidence alone was insufficient to establish protocols. One publication described the use of the Delphi method combined with the nominal group method to achieve consensus in developing guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock.11 In this document, investigators provided specific information about the iterative process they used to funnel disparate opinions into a manageable set of questions, and about how they quantified the convergence of opinions. The process developed for this project is a modification of the one used for the sepsis guidelines.11 We used the principles and practices of the Delphi method12 and Nominal Group Method13 to conduct this project.

Participants were organized into subgroups of prehospital care, emergency medicine, neurosurgery, and intensive care, according to their expertise and background with a moderator for each subgroup. A month in advance of the meeting, each subgroup was provided with preparation material, which included the scientific evidence on specific interventions for each area, as well as CPGs—those based on evidence and those based on expert consensus.14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 The questions were allocated to each subgroup, and in the first session (day 1), through a series of voting rounds, an agreement was reached among the subgroups. A 70% agreement rate was required to specify each recommendation. Next, a representative of each subgroup presented its recommendations to the entire group, which discussed the recommendations considering the scientific evidence and expert opinion. The entire group then voted on each recommendation and continued this iterative process of discussion and voting until a 90% agreement rate was obtained to endorse a recommendation. Facilitators of the methodological team support the discussion and voting sessions all the time.

In the final session, management algorithms were presented, which integrated the recommendations, adjusted, and stratified according to the availability of resources in centers of varying complexity. The product was named as BOOTStraP—Beyond One Option for Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury: A Stratified Protocol (Supplementary Material S1 [online only]).

Results

How to Interpret and Use the Proposed Algorithms

We have created categories for each treatment phase, according to real scenarios presented by experts from different regions of the country, and identified in different surveys36 37 during the development of the Colombian TBI guidelines.

-

Prehospital: Basic ambulance or BET; medical ambulance or AET.

-

Emergency care: Low complexity (without CT), medium–high complexity with CT.

-

Neurological surgery: Does not have neurosurgery available; has neurosurgery but no ICU availability.

-

Intensive care: Has an intermediate care unit but no ICU availability and no neurosurgery availability; has ICU and neurosurgery availability.

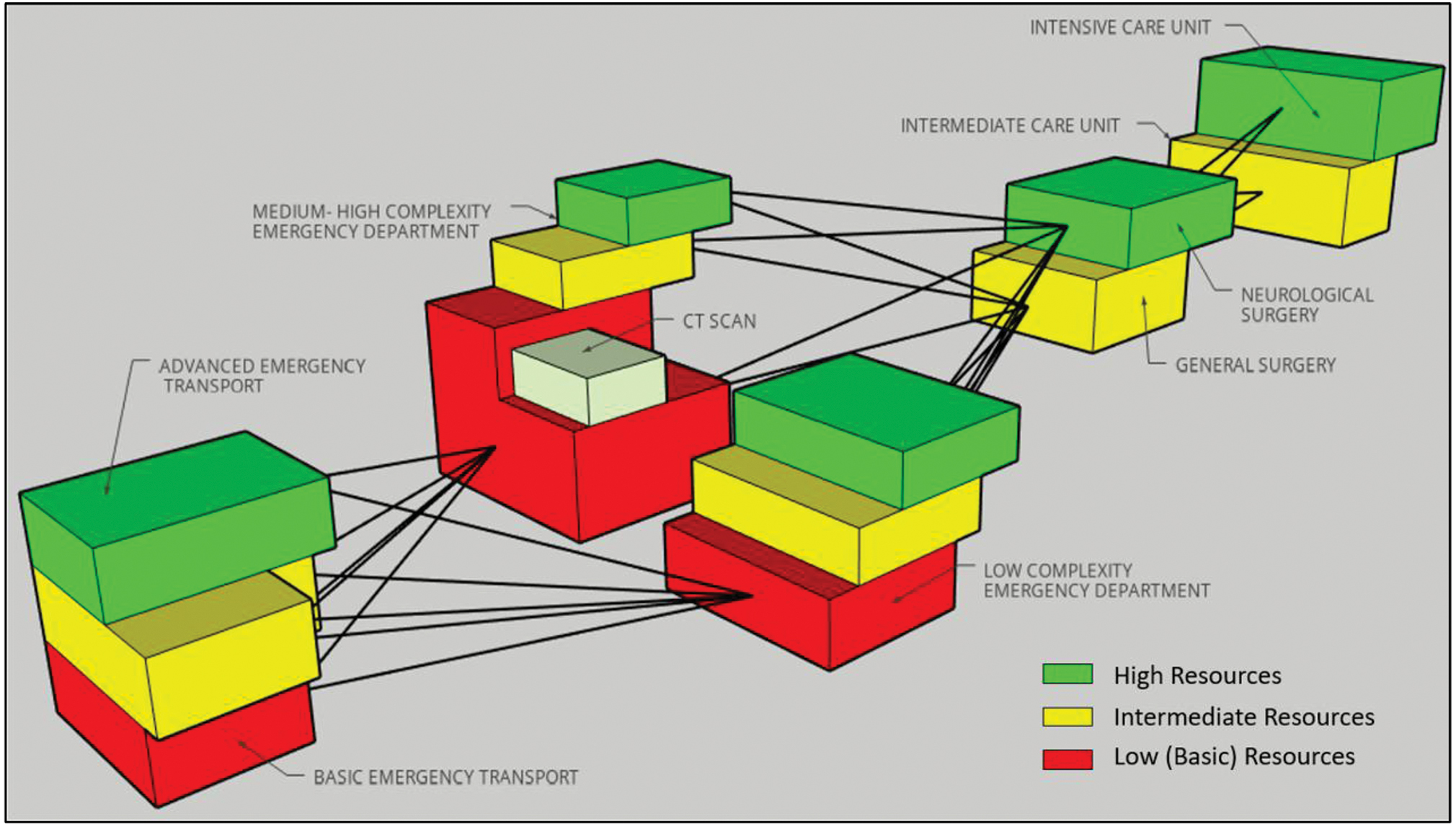

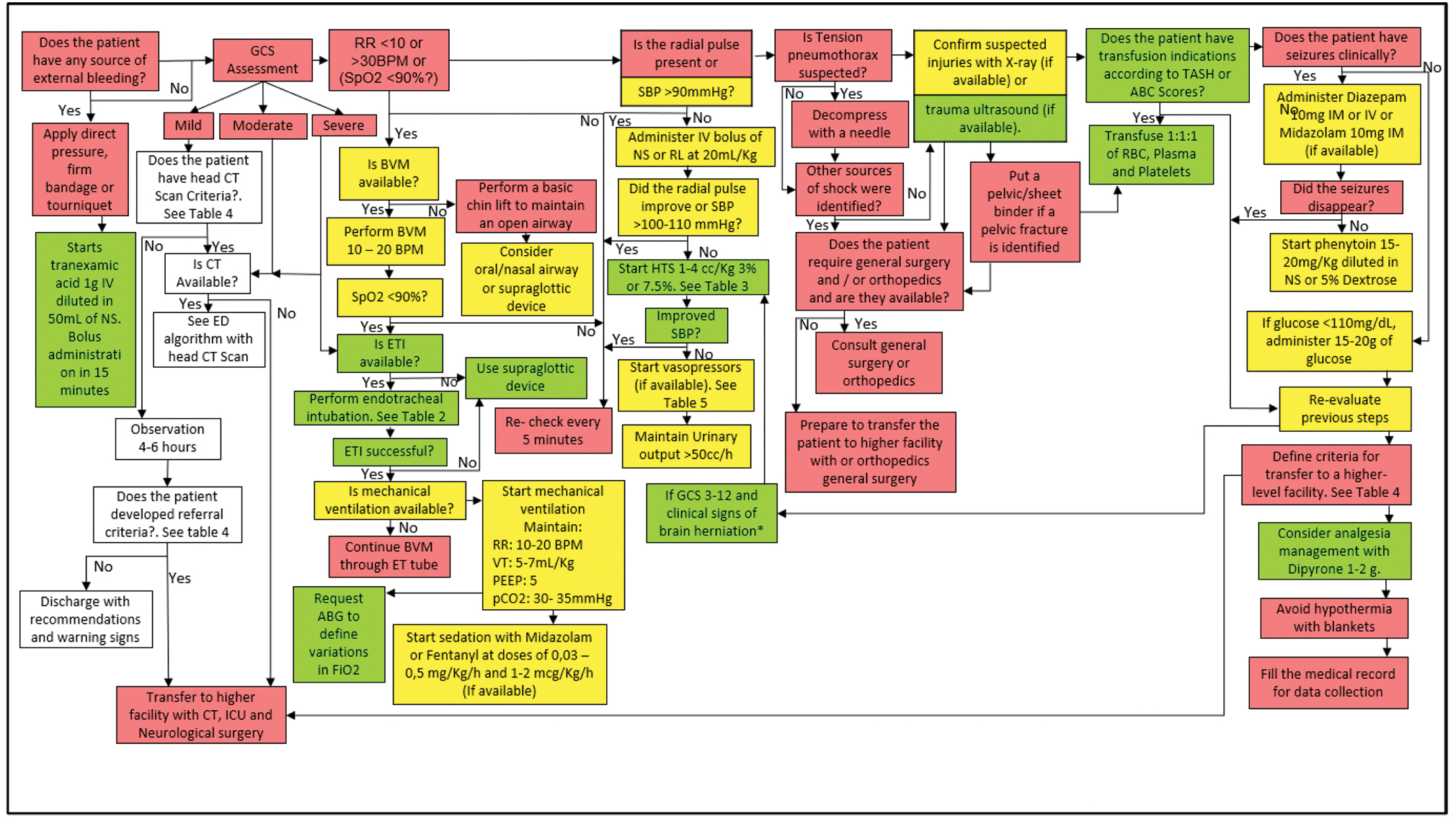

Therefore, the algorithms for treatment shown later are not organized according to strict categorizations. They are stratified. In this way, a medical provider in any of the four treatment phases can select the best practice treatment option, depending on the available resources as shown in Fig. 1. The treatment options in the algorithms below are presented in red, yellow, or green background. A red background indicates the proposed intervention can be performed in the lowest level of resources; a yellow background indicates the intervention can be performed at a medium level of resources, and green background indicates the interventions are regularly performed in the most advanced level of resources. All the options (proposed interventions) can be selected from the algorithms and organized in different levels of care according to the availability of the mentioned resources.

-

Fig. 1 Three-dimensional stratified scheme according to the level of resources and complexity.

Fig. 1 Three-dimensional stratified scheme according to the level of resources and complexity.

Questions 1 and 2

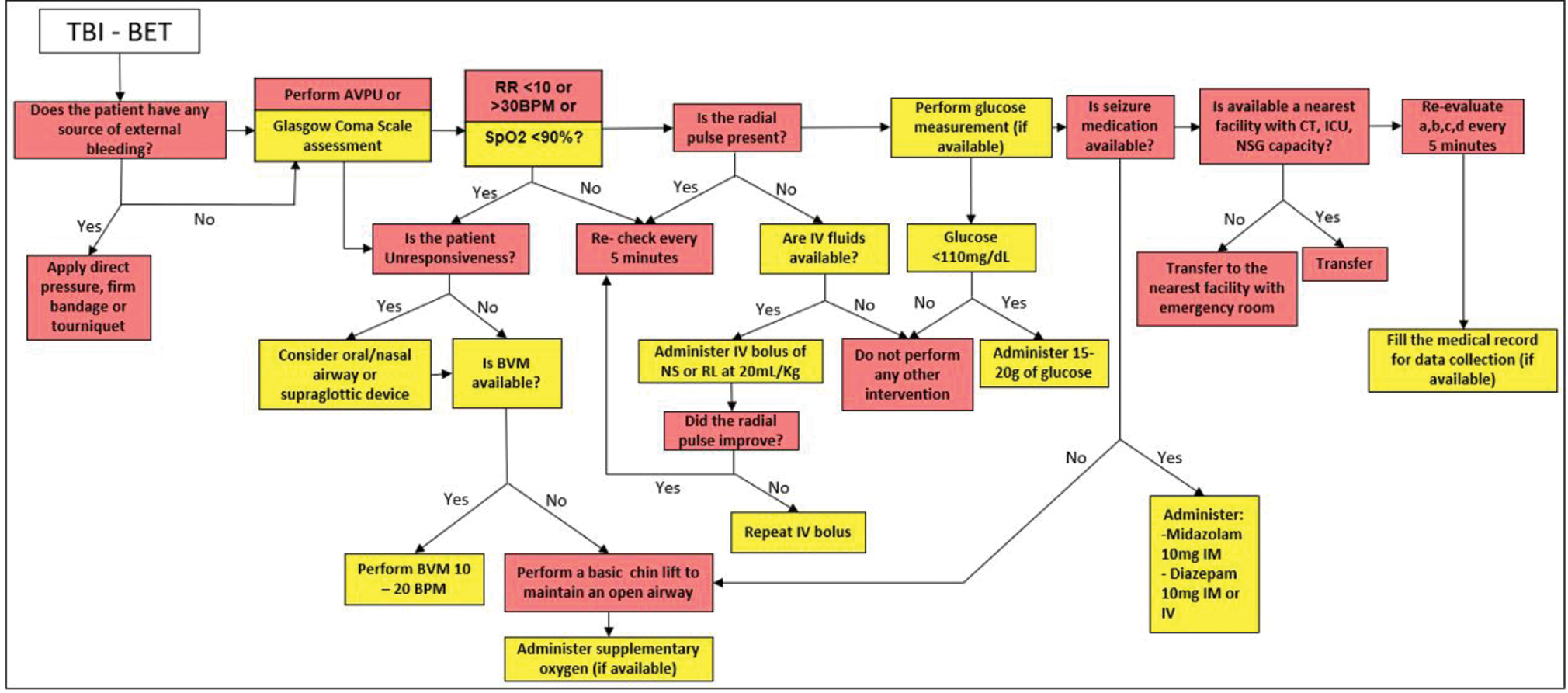

What is the best protocol for treating an adult patient with mild, moderate, or severe TBI in a BET?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended that the management of adult patients who present with mild TBI (without criteria for prehospital care or transfer in an AET) can be performed in a BET. However, if the planned transfer is longer than 30 minutes, and AET should be requested if available.

-

It is recommended that no patient with moderate or severe TBI be transported in a BET, but if this situation occurs in any region, algorithm in Fig. 2 should be followed.

-

To determine the requirement for prehospital care and transfer, parameters such as the mechanism of injury, type of injury, clinical status, age, comorbidities, history, and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) should be evaluated.

-

Fig. 2 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in basic emergency transport (BET).

Fig. 2 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in basic emergency transport (BET).

Questions 3 and 4

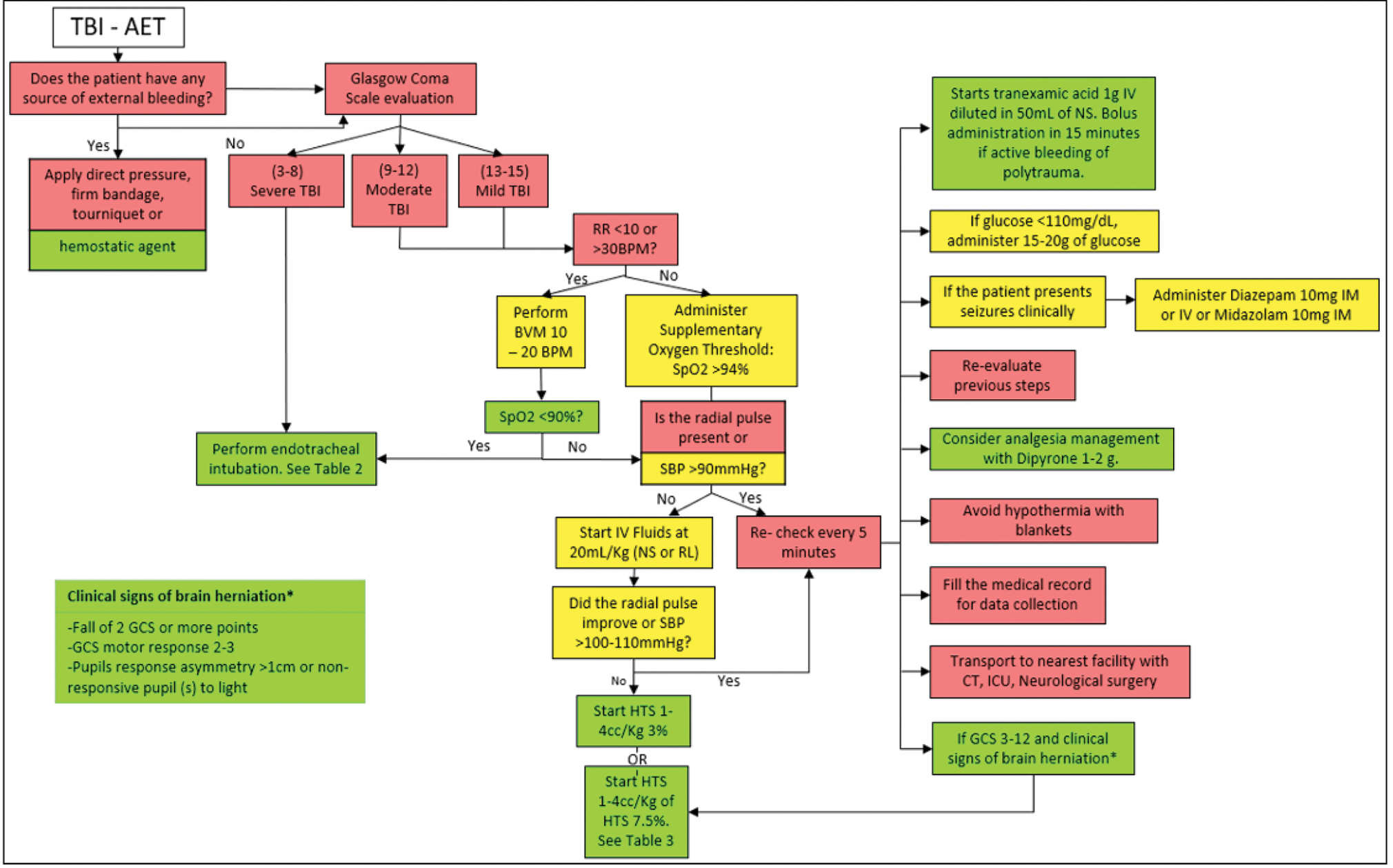

What is the best protocol for treating an adult patient with mild, moderate, or severe TBI in an AET?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended not to remain at the scene for more than 30 minutes, regardless of the patient’s clinical status because the time at the scene can diminish the possibility of a good neurological result. The GCS to classify the severity of the injury in the patient should be performed after the initial resuscitation.

-

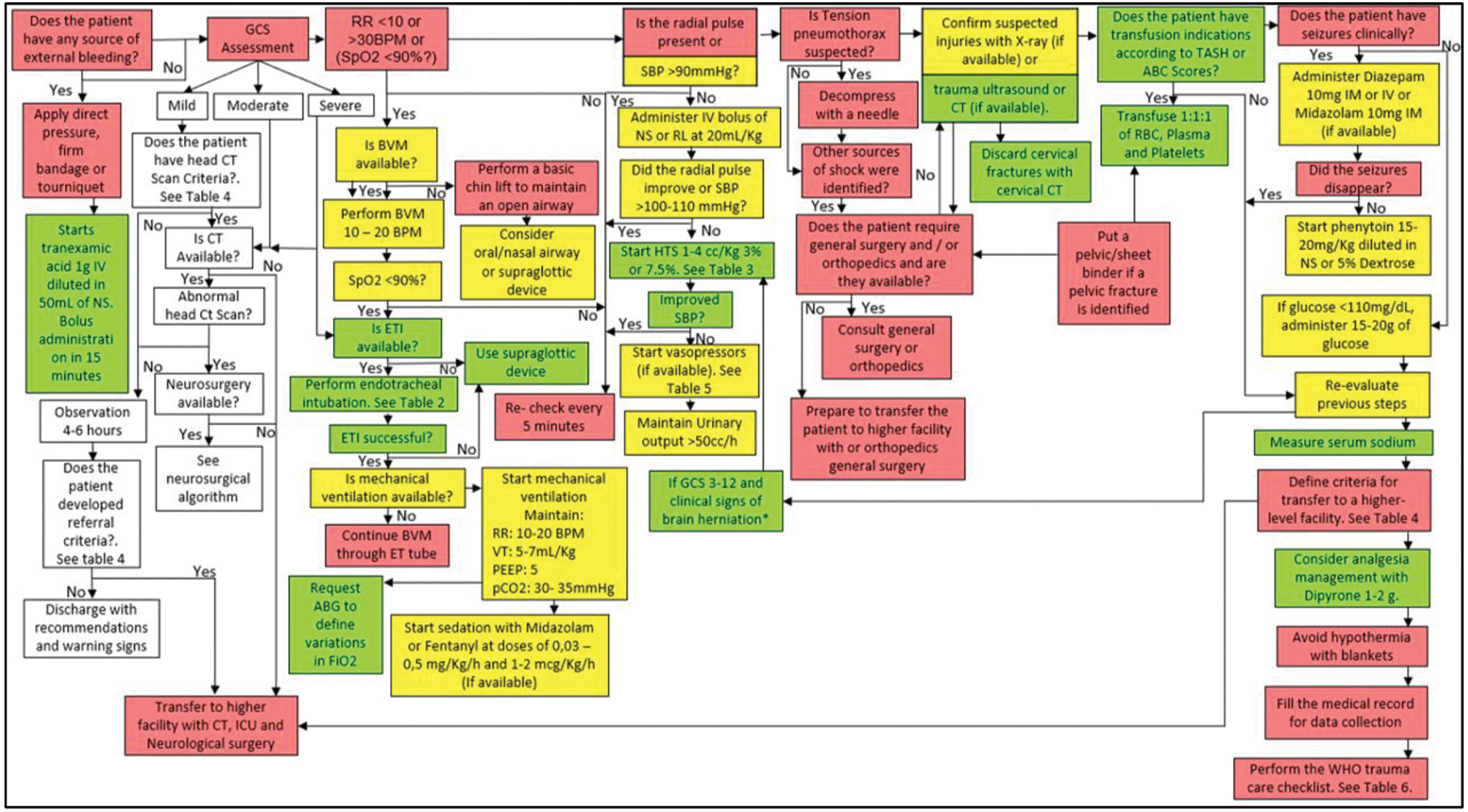

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 3, including interventions shown in Tables 2 3.

-

Fig. 3 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in advanced emergency transport (AET).

Fig. 3 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in advanced emergency transport (AET).

Question 5

What is the best protocol for managing an adult patient with mild TBI in a low complexity ED (without CT)?

Recommendation

-

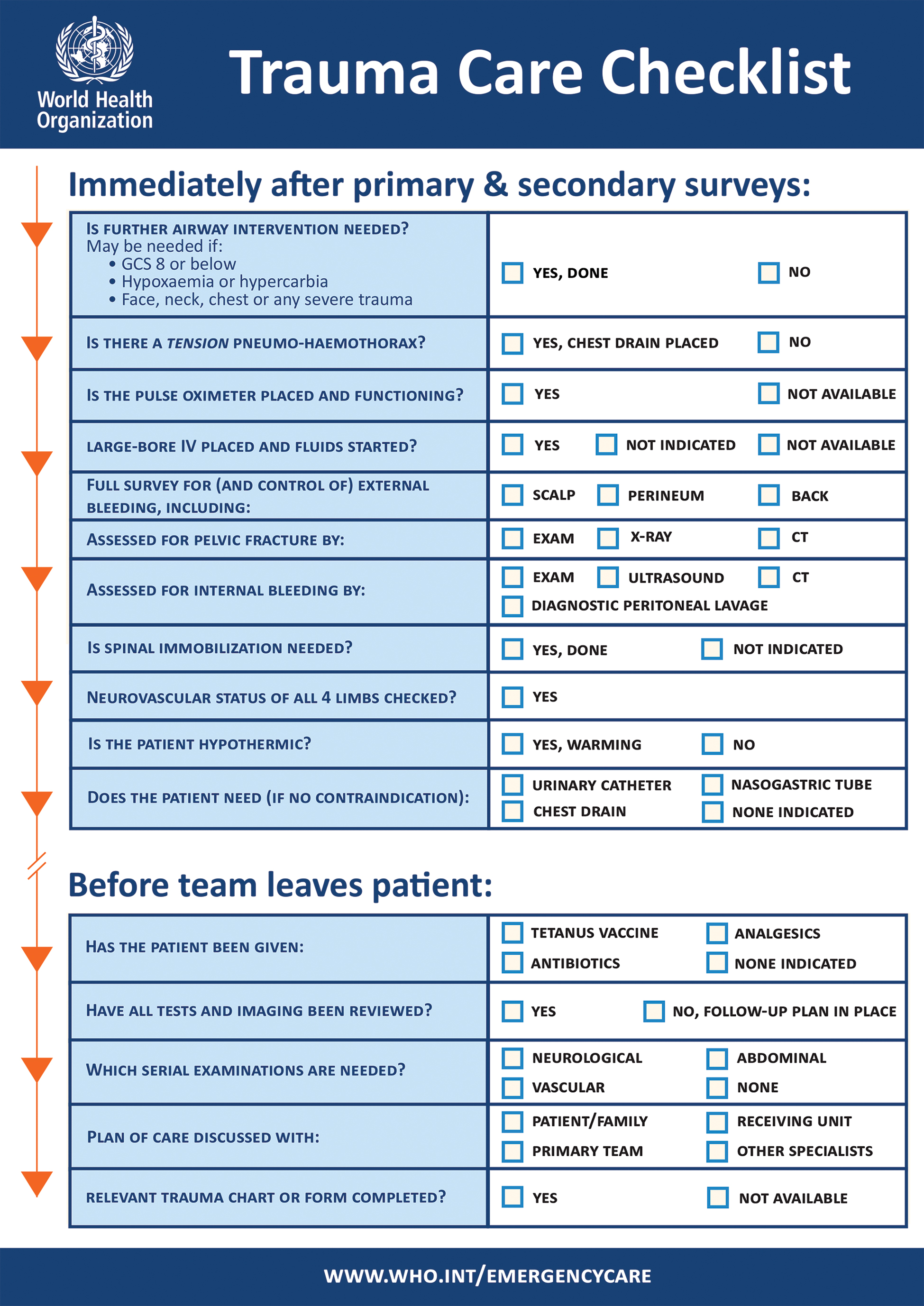

Every mild TBI patient who enters the ED should be treated for any life-threatening event according to the advanced trauma life support (ATLS) primary evaluation,38 including those with penetrating injuries to the head. Patients presenting with a penetrating injury to the head and/or any abnormal finding in the primary clinical evaluation should be referred to a center of high complexity for neuroimaging (see CT reading suggestions at Appendix A in (Supplementary Material S2 [online only]), evaluation by the neurosurgery service, and integrated management according to the criteria in Tables 4 5 Fig. 4.

-

If the patient does not have abnormal findings in the primary clinical evaluation, or does not have a penetrating brain injury, or does not meet the referral criteria in Table 4, the patient should be observed in the ED. After 4 to 6 hours of observation, if the patient does not develop referral criteria (Table 4), consider discharge with recommendations and warning signs.

|

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow coma scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury. |

|

It is recommended that patients with moderate to severe TBI (GCS 3–12) should be transferred immediately to high level of care hospitals with access to neuroimaging and neurosurgery |

|

It is recommended that patients with mild TBI (GCS 13–15) who present one or more of the following criteria be referred for evaluation at an institution that has access to neuroimaging and neurosurgery: |

|

GCS under 15 up to 2 h after injury |

|

Severe headache |

|

More than two episodes of vomiting |

|

Skull fracture, including depressed fractures or clinical signs of fracture of the skull base (raccoon eyes, retroauricular ecchymosis, otorrhea, or rhinorrhea) |

|

Age older than or equal to 60 y |

|

Blurred vision or diplopia |

|

Posttraumatic seizure |

|

Focal neurological deficit |

|

Previous craniotomy |

|

Fall of more than 1.5 m |

|

Retrograde amnesia more than 30 min and/or anterograde amnesia |

|

Suspected intoxication with alcohol and/or psychoactive substances |

|

It is recommended that patients with mild TBI and who are in active treatment with anticoagulants, have active coagulopathies, or are pregnant should be transferred to centers with neurosurgery and neuroimaging services |

|

Medication |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Vasopressor therapy |

Noradrenaline |

Adrenaline |

|

Amp × 4 mg/4 mL |

Amp × 1 mg/mL |

|

|

Dose:0.05–0.5 μg/kg/min |

Dose: 0.1–2 μg/kg/min |

|

-

Fig. 4 Trauma Care Checklist. Source: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/trauma-care-checklist

Fig. 4 Trauma Care Checklist. Source: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/trauma-care-checklist

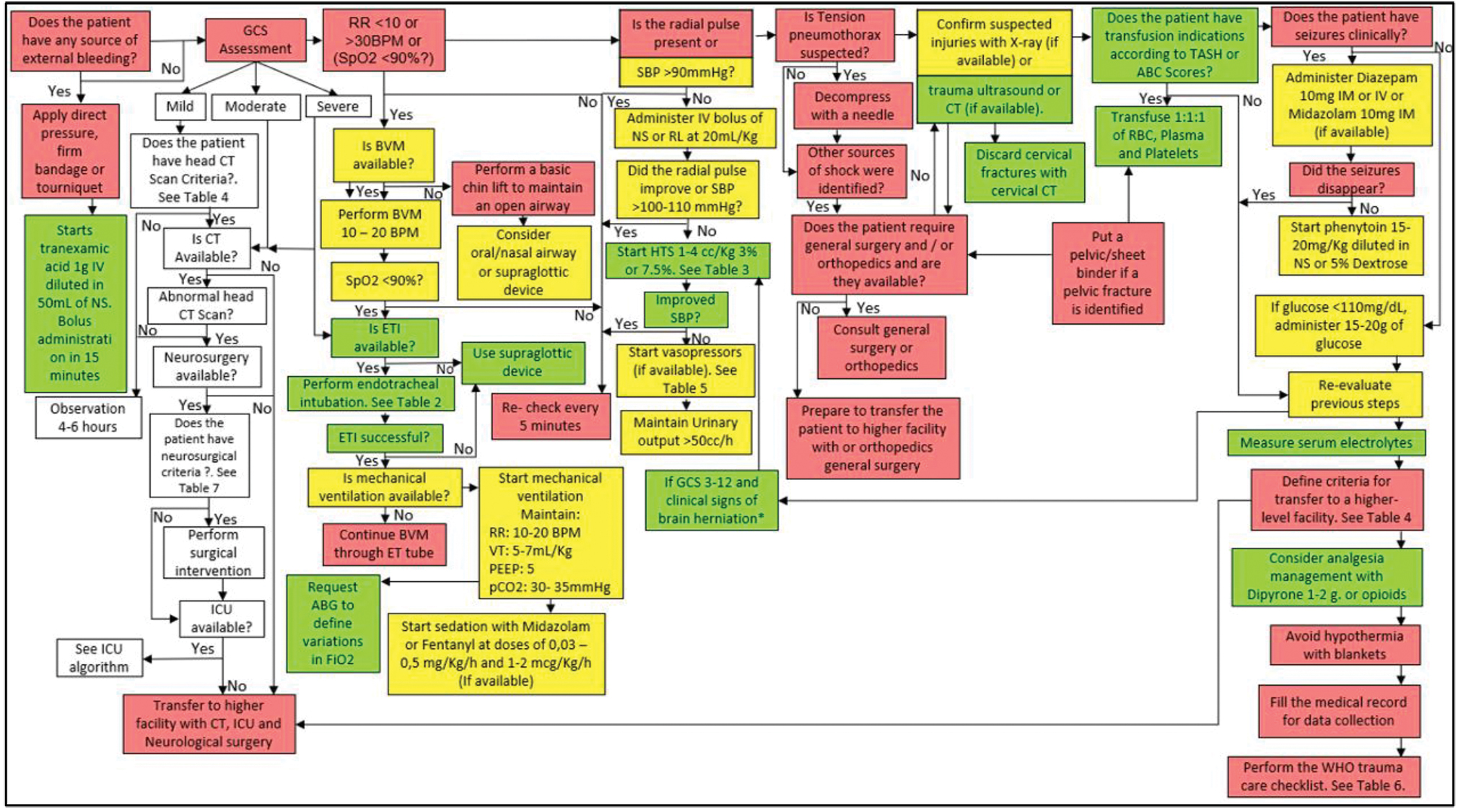

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 5.

-

Fig. 5 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a low complexity ED (without CT).

Fig. 5 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a low complexity ED (without CT).

Questions 6

What is the best protocol for managing an adult patient with mild TBI in a medium or high complexity ED (with CT scan)?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended that adult patients with mild TBI who enter the ED of medium or high complexity centers complete a comprehensive assessment as described by the ATLS recommendations.38

-

It is recommended to define neuroimaging requirements according to Table 4, and then perform an interpretation of the CT as normal or abnormal. If the patient does not meet the criteria for a head CT scan or if the CT is normal, the patient should be observed for 4 to 6 hours, then determine if hospital discharge with recommendations and warning signs is appropriate. If the CT is abnormal, request an assessment by the neurosurgery service to determine medical or surgical management.

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 6.

-

Fig. 6 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a medium or high complexity emergency department (ED) (with computed tomography [CT]).

Fig. 6 Management algorithm of the patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a medium or high complexity emergency department (ED) (with computed tomography [CT]).

Question 7

What is the best protocol for managing an adult patient with moderate to severe TBI in a low complexity ED (without CT)?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended that adult patients with moderate to severe TBI who enter the ED of low complexity centers receive a comprehensive evaluation as described by the ATLS, through primary and secondary evaluation,38 and prepare the patient for immediate referral under the best conditions to the nearest center with availability of neurosurgery and neuroimaging as shown in Fig. 5.

Question 8

What is the best protocol for managing an adult patient with moderate to severe TBI in a medium or high complexity ED (with CT scan)?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended to manage an adult patient with moderate to severe TBI in an ED of medium or high complexity, when available.

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 6.

Question 9

What is the best protocol to determine if a patient with TBI requires immediate surgery?

Recommendation

-

To determine those patients admitted to the ED with TBI that require immediate surgical intervention, the patient must have one or more clinical criteria and one or more imaging criteria (Table 6). It is recommended that a neurological examination be performed after adequate resuscitation in the emergency room to determine the clinical criteria.

-

It is suggested that personnel with appropriate training provide strict neurological follow-up to a patient who presents clinical criteria without imaging criteria, or imaging criteria without clinical criteria. Surgery may be indicated in the patient with neurological impairment, defined as a decrease in the GCS of more than 2 points.

-

Finally, it is suggested that patients who, after adequate resuscitation, have bilateral mydriasis and a score of 3 on the GCS, should be assessed by the neurosurgeon to determine whether to perform a quick surgical procedure or not.

|

Clinical criteria |

Imaging criteria |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviation: GCS, Glasgow coma scale. Note: One clinical criterion + one imaging criterion = surgical indication. One isolated clinical criterion = medical management. One isolated imaging criterion = medical management. |

|

|

Pupillary asymmetry with 1 mm of difference |

Midline shift > 5 mm |

|

GCS motor response of 4 or less |

Total cisterns compression (Grade III) |

|

Epidural hematoma ≥ 30 mL in volume |

|

|

Intracerebral hematoma ≥ 50 mL in volume |

|

|

Subdural hematoma > 10 mm in width |

|

|

Posterior fossa hematoma with hydrocephalus |

|

Question 10

What is the best protocol to manage a patient who requires immediate surgery in a health care facility that does not have neurosurgery?

Recommendation

-

Many hospitals in low-resource settings do not have a neurosurgery service; those located in remote rural areas. It is recommended that close communication occurs between the lower level facility and the referral site to ensure appropriate management during the transportation of patients who will undergo surgery to avoid secondary complications (Table 7).

|

Medium complexity |

High complexity |

|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; TBI, traumatic brain injury. |

|

|

Hospitalization |

Hospitalization |

|

Radiology and diagnostic imaging, CT scan |

Surgery |

|

Clinical laboratory, arterial gases |

Intensive care |

|

Pharmaceutical service |

Intensive neonatal care (if pediatric center) |

|

Sterilization process |

Physiotherapy or respiratory therapy |

|

Blood transfusion |

Pharmaceutical service |

|

Pathology |

Radiology and diagnostic imaging |

|

Respiratory therapy |

Clinical laboratory |

|

Nutrition |

Blood transfusion |

|

Transportation assistance |

Hospital support services |

|

Transportation assistance |

|

|

Sterilization process |

|

|

Pathology |

|

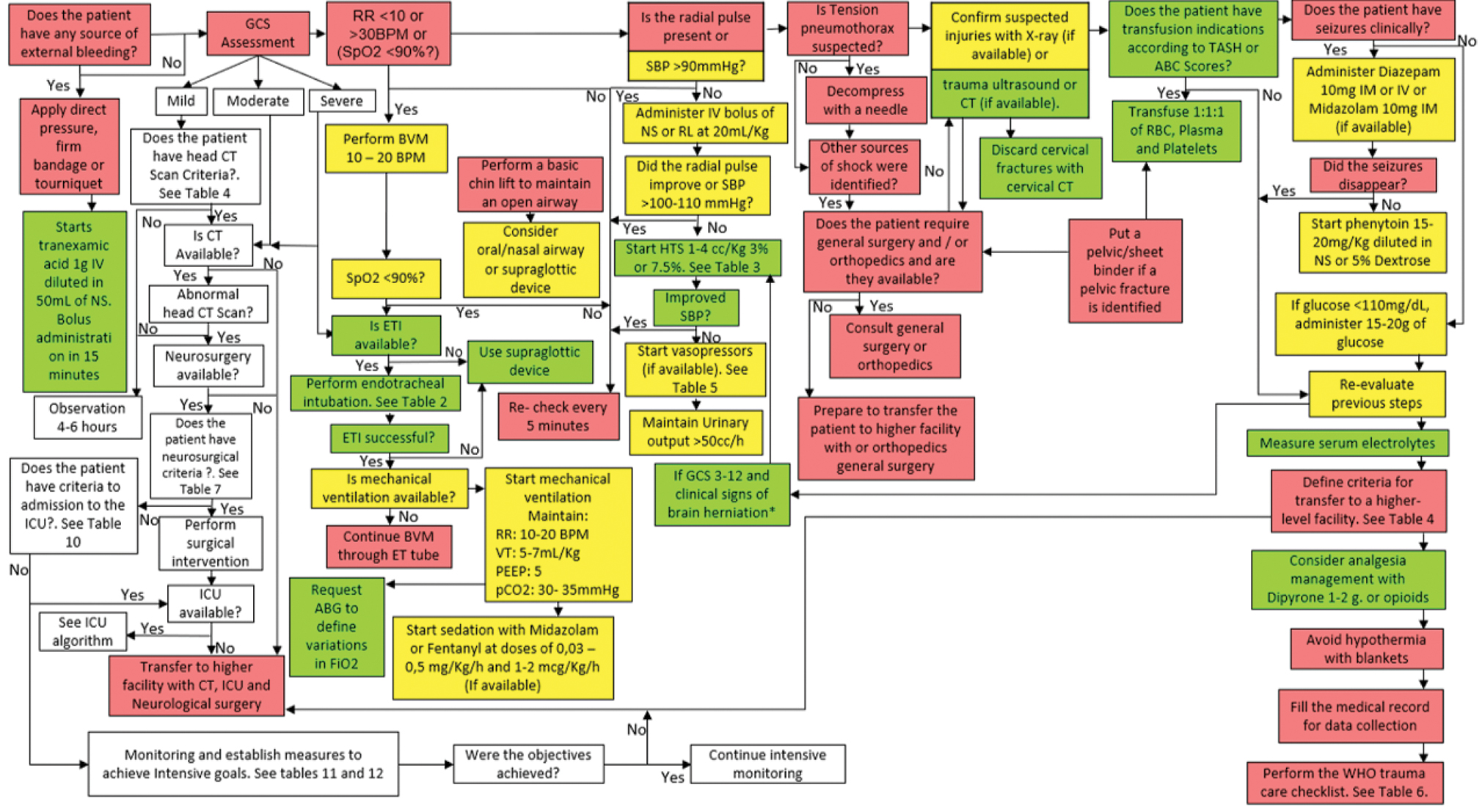

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 7.

-

Fig. 7 Management algorithm of patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who requires immediate surgery.

Fig. 7 Management algorithm of patient with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who requires immediate surgery.

Question 11

What is the best protocol to manage a patient who requires immediate surgery in a medical center that has neurosurgery but no ICU?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended to perform surgery for a patient with TBI that meets the criteria for immediate surgery (Table 6) in the context of a hospital that has a neurosurgery service and anesthesiologist but does not have an ICU. During the immediate postoperative period, a referral to a medical center with an ICU should be requested. If such a center is available, the patient should be transported immediately. If not, the patient should be maintained with mechanical ventilation and sedation (Table 8). See the algorithm shown in Fig. 7.

|

Target RASS |

RASS description |

|---|---|

|

+4 |

Combative, violent, danger to staff |

|

+3 |

Pulls or removes tube(s) or catheters; aggressive |

|

+2 |

Frequent non purposeful movement, fights ventilator |

|

+1 |

Anxious, apprehensive, but not aggressive |

|

0 |

Alert and calm |

|

−1 |

Awakens to voice (eye opening/contact) > 10 s |

|

−2 |

Light sedation, briefly awakens to voice (eye opening/contact) < 10 s |

|

−3 |

Moderate sedation, movement, or eye opening. No eye contact |

|

−4 |

Deep sedation, no response to voice, but movement or eye opening to physical stimulation |

|

−5 |

Unarousable, no response to voice, or physical stimulation |

Question 12

What is the best protocol to manage a patient with moderate to severe TBI in service of intermediate care (no ICU) in a health care center of medium complexity?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended that the management of adult patients with moderate to severe TBI takes place in a medium complexity care center that has intermediate care if it does not meet ICU criteria (see Table 9). The criteria to determine a center of medium complexity are shown in Table 10.

-

All patients who are hospitalized in intermediate care in medium complexity centers should be monitored for evaluation and management with an emphasis on the prevention of secondary injury and the progress of the primary lesion. For this purpose, target maintenance of parameters is shown in ►Tables 10 and 11.

|

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; GCS, Glasgow coma scale. |

|

GCS: ≤ 12 with or spinal cord injury |

|

ICU support for any other system |

|

Planned trauma surgery urgent (24 h) |

|

Comorbidities: (anticoagulated patients, liver failure, chronic kidney disease in dialysis, heart failure, epilepsy, or who are being treated with ASA/clopidogrel) |

|

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; INR, international normalized ratio. |

|

Maintain oxygenation with saturation more than 90%, PaO2 more than 60 |

|

Maintain PaCO2 in normal parameters for age and height above sea level |

|

Keep lactate levels less than 2 mmol/L |

|

Maintain systolic blood pressure ≥ 100 mm Hg in patients between 50 and 60 years of age, or 110 or more for patients aged 15 to 49 or older than 70 y |

|

Keep heart rate at normal levels (60–90 bpm) |

|

Monitor the appearance of seizures without prophylactic treatment |

|

Evaluate the neurological condition of the patient, if there is a Glasgow coma scale change of more than 2 points, it is recommended to perform an image evaluation |

|

Maintain glucose levels between 110 and 170 mg/dL to avoid hypoglycemia |

|

Keep temperature between 36 and 37.5°C is suggested to not perform prophylactic or therapeutic hypothermia, if there is spontaneous hypothermia do not perform active rewarming. Ensure that the patient is in regulated normothermia |

|

Keep sodium levels between 135 and 155 mmol/L |

|

Maintain normal levels of other electrolytes |

|

Maintain normal levels of coagulation tests: INR less than 1.5, platelets more than 100,000/UL and fibrinogen more than 150 mg |

|

Maintain hemoglobin above 9 g/dL |

|

Initiate orally intake early according to tolerance and check for contraindications |

|

Initiate mechanical thromboprophylaxis in the first 24 h and pharmacological prophylaxis after 24 h if there are no hemorrhagic lesions and after 48 h if the hemorrhagic lesions are stable in the CT scan |

|

Evaluation and rehabilitation according to the patient condition in the first 48 h |

It is recommended to follow the algorithm shown in Fig. 8.

-

Fig. 8 Management algorithm of patient with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in service of intermediate care.

Fig. 8 Management algorithm of patient with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in service of intermediate care.

Question 13

What is the best protocol to manage a patient with moderate to severe TBI in an ICU within a center of medium–high complexity?

Recommendation

-

It is recommended that the management of adult patients with moderate to severe TBI in a medium–high complexity health care center be performed in the ICU if it meets the established criteria shown inTable 7 (see Supplementary Material S1, Algorithm 10 [online only]).

-

Specialized medical personnel should carry out the management of such a patient with the availability of face-to-face neurosurgeon consultation.

-

When the patient arrives in the ICU, they should evaluate: complete medical record with emphasis on physical, neurological, and paraclinical exams performed so far; verify oxygenation status, hemodynamic status, and presence of other injured organs, especially cervical spine injury; and additionally to perform identification, prevention, and management of secondary injury (Table 12) (see Supplementary Material S1, Algorithm 10 [online only]).

-

The management of the patient in the ICU should emphasize the prevention of secondary injury and the prevention of the progress of the primary injury, for which the patient should be monitored, with a target to maintain the parameters according to the proposed criteria (Tables 9 10 11) (see Supplementary Material S1 S2 S3, Appendix B [online only]).

|

Abbreviations: GCS, Glasgow coma scale; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; TBI, traumatic brain injury. |

|

Cardioscope, pulse oximeter, MAP |

|

Arterial blood gas |

|

Follow GCS, pupil reactivity, and motor deficit every hour |

|

Follow vital signs every hour |

|

Monitoring the temperature by the axillary route and every hour |

|

Glycemia monitoring every 8 h |

|

Monitoring daily sodium except if it has osmotic therapy or dysnatremias. In this case, it needs to be monitoring more often |

|

Monitoring of K, Mg, Cl daily or at the doctor’s discretion |

|

Monitoring of PT, PTT, fibrinogen, platelets should be repeated if they are altered according to medical criteria |

|

Monitoring hemoglobin levels every day |

|

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; ICP, intracranial pressure; INR, INR, international normalized ratio; RASS, Richmond agitation–sedation scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury. |

|

Cardioscope |

|

Pulse oximeter |

|

Capnography |

|

Invasive blood pressure |

|

Central venous catheter |

|

Jugular bulb catheter |

|

Urinary catheter |

|

Watch the sedation state according to the RASS scale |

|

Watch the neurological status with the GCS and the four scale |

|

Monitor the clinical status of the patient with an emphasis on pupillary reactivity, and motor deficit |

|

It is recommended to use continuous EEG if available, especially in patients with unexplained altered consciousness, or patients with GCS of 8 or less with cortical injury, depressed fracture, or penetrating injury |

|

Following vital signs every hour |

|

Monitoring the temperature: It is recommended to measure the central temperature if available, otherwise perform the axillary temperature measurement |

|

Glucose monitoring every 4 h |

|

Monitoring daily sodium except if the patient has osmotic therapy or if the patient does not have dysnatremia |

|

Monitoring of K, Mg, Cl daily or at doctor’s discretion |

|

Monitoring of coagulation is suggested: thromboelastogram measurement, TP, PTT, fibrinogen, and platelets, which should be repeated if they are altered or medical criteria |

|

Monitoring Hb levels every day |

|

Monitoring of ICP in patients with GCS less than 8 and abnormal CT |

|

Doppler monitoring is recommended for all patients in the sites where this resource is available, measuring the pulsatility index and vascular reactivity with reserve |

|

PTiO2 monitoring: Measurement is recommended for all patients in the places where this resource is available |

|

Maintain oxygenation with saturation more than 90%, PaO2 more than 60 mm Hg |

|

Keep PaCO2 in normal parameters for age and height above sea level |

|

SBP ≥ 100 mm Hg in patients between 50 and 60 y of age, or 110 mmHg or more for patients aged 15 to 49 or older than 70 y |

|

CPP between 60 and 70 and varies according to metabolic needs |

|

Keep heart rate at normal levels (60–90) |

|

Urinary output between 0.5 and 3 mL/kg/h |

|

Monitor the onset of seizures, and if it has EEG indications |

|

Preserve the clinical neurological condition of the patient and before a change of GCS more than 2 points perform evaluation by images |

|

Keep glucose levels between 110 and 170 mg/dL to avoid hypoglycemia |

|

Maintain temperature between 36 and 37.5°C. It is suggested not to perform prophylactic or therapeutic hypothermia and if there is spontaneous hypothermia, do not do active rewarming, and maintain regulated normothermia |

|

Keep sodium levels between 135 and 155 mmol/L |

|

Keep normal levels of other electrolytes |

|

Keep normal levels of coagulation tests: INR less than 1.5, platelets more than 100,000/UL and fibrinogen more than 150 mg |

|

Keep lactate levels less than 2 mmol/L |

|

Maintain hemoglobin above 9 g/dL |

|

Initiate enteral nutrition early. Evaluate tolerance and without contraindications |

|

Initiate mechanical prophylaxis in the first 24 h. And then, pharmacological thrombus prophylaxis after 24 h if there are no hemorrhagic lesions and after 72 h if the hemorrhagic lesions are stable in the CT scan |

|

Keep ICP at levels lower than 18–20 mm/Hg in the first 24 h and 22 mm/Hg after 24 h |

|

Brain tissue oxygen tissue (PtiO2) must be more than 25 mm/ Hg and less than 55 mm Hg |

|

Maintain venous jugular oxygen saturation (SjO2) more than 55% |

|

Evaluation and rehabilitation, according to the patient’s condition in the first 48 h |

Discussion

Current evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of TBI were generated from studies conducted in developed countries.15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 39 It is estimated that 80% of the global population live in developing economies40 in which access to resources required for optimum treatment is limited. There are few guidelines focused on the management of TBI in low and middle income countries with organized international methodology.8 34 Most of these guidelines, developed in high and low–middle income countries do not fill the gaps of different scenarios in real-life situations due to the methodology itself, attached to the evidence-based methodological science.40 41 42 43 44 In real circumstances, not all the resources are always available on time, especially in LMICs.45 The present effort is focused on filling these gaps with a mixed methods approach combining evidence-based recommendations and expert opinion where there is no evidence-based medicine to develop helpful recommendations for real-life situations in different context with resources level variation. The BOOTStraP is two dimensional. The first dimension is the treatment phase (prehospital care, ED, surgery, and ICU). The second dimension is the level of resources. Resource availability in LMICs is ever-changing. Even a high-resource center can find itself without enough medications, or with a sudden loss of personnel. Furthermore, one system may have enough resources in one treatment phase (e.g., ED) but insufficient resources in another (e.g., emergency transport). While the two-dimensional categorization in Fig. 1 is over-simplified, it illustrates the territory, and we attempted to cover with the stratified treatment options of BOOTStraP (Supplementary Material S1, available online only).

The strength of this project includes the participation of experts from different specialties since they contribute to connecting the guidelines between the different dimensions. On the contrary, the color teaching material makes it easier for interested people to apply the recommendations according to the context in which they are.

Limitations of this project are the noninclusion of patients younger than 15 years, therapies or tools undergoing experimentation, and the direct nonadvocacy of primary prevention and the rehabilitation process since they were outside the scope of this consensus.

Future steps for this project will include (1) to disseminate BOOTStraP globally, performing an external validation of the exercise by an international group of experts, with the support of international collaborators such as the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies, the WHO, and the Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma from the United Kingdom and (2) to conduct a study to measure its influence on outcomes for patients with TBI in low-resource environments.46 47 51

BOOTStraP is intended to be a practical handbook for care providers to use to treat patients with TBI whatever resources are available. BOOTStraP is an attempt to provide treatment options to 80% of the world’s population, in regions of LMICs economies, where disparities in health care resources and workforce exist daily, challenging the application of guidelines and protocols developed for HICs.51

Conclusion

Current evidence-based recommendations of the guidelines for the treatment of TBI are generated with significant flaws in aspects where evidence does not exist or is limited. Knowledge transferability of these recommendations to practice generates critical disconnection from real scenarios were training, or resources are limited. Development of expert consensus-based recommendations, even for areas were training or resources are weak or absent, is possible using validated methodologies. Stratification of recommendations for interventions according to the availability of the resources on different stages of integral care is a proposed method for filling gaps in actual evidence, to organize a better strategy for interventions in different real-life scenarios. We develop 10 algorithms of management for building TBI protocols based on expert consensus to articulate treatment options in prehospital care, EDs, neurological surgery, and intensive care, independent of the level of availability of resources for care.

Note

No human subjects were involved in this work.

Authors’ Contributions

Andrés M. Rubiano, MD, PhD(c): Principal investigator, senior author.

David S. Vera, MD, José N. Carreño, MD, Oscar Gutiérrez, MD, Jorge Mejía, MD, MSc, Juan D. Ciro, MD, Ninel D. Barrios, MD, Alvaro R. Soto, MD, Paola A. Tejada, MD, MSC, PhD, Maria C. Zerpa, MD, Alejandro Gómez, TAPH, MD, Norberto Navarrete, MD, MSc, Oscar Echeverry, TAPH, Mauricio Umaña, MD, Claudia M. Restrepo, MD, José L. Castillo, MD, Oscar A. Sanabria, MD, Maria P. Bravo, MD, Claudia M. Gómez, MD, Daniel A. Godoy, MD, German D. Orjuela, TAPH, Augusto A. Arias, MD, Raul A. Echeverri, MD, Jorge Paraños, MD: Coinvestigators, coauthors.

Jorge H. Montenegro, MD, Nancy Ann Carney, PhD, and Angelica Clavijo MD: Coninvestigators, coauthors also.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma is supporting Dr. Rubiano research work. The group was commissioned by the NIHR using Official Development Assistance funding (project 16/137/105). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, NIHR, or the UK Department of Health.

References

- Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. (9995)

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2018;4:1-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rural risk: geographic disparities in trauma mortality. Surgery. 2016;160(6):1551-1559.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a rural trauma system on traumatic brain injuries. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(7):1189-1197.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical disparity and traumatic brain injury in America: rural areas suffer poorer outcomes. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2019;10(1):10-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Violence and Injury Prevention, Global status report on road safety 2015. Available at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2015/en/. Accessed November 30, 2018

- Colombian Institute of Forensic Sciences and Legal Medicine. Forensic. Data for Life. 2018. Available at: http://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/documents/20143/262076/Forensis+2017+Interactivo.pdf/0a09fedb-f5e8-11f8-71ed-2d3b475e9b82. Accessed November 30, 2018

- Colombia. Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Colciencias, MEDITECH Foundation. Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with severe Traumatic Brain Injury. GSSSH – 2014. Available at: http://gpc.minsalud.gov.co/gpc_sites/Repositorio/Conv_563/GPC_trauma_craneo/CPG_TBI_professionals.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2018

- Colombian Ministry of Health, Resolution 3100 of 2019. Available at: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/resolucion-3100-de-2019.pdf

- Mock C, Lormand JD, Goosen J, Joshipura M, Peden M. Guidelines for essential trauma care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004 Available at: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/services/guidelines_traumacare/en/

- Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ. 2008;337:a744.

- [Google Scholar]

- Building consensus in health care: a guide to using the nominal group technique. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9(3):110-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical practice guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(3):257-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Part 1. Organization of neutrauma-care system and diagnosis. Guidelines for practitioners. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N Burdenko. 2015;79(6):86-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of severe traumatic brain injury. Part 2. Intensive care and neuromonitoring] Vopr Neirokhir. 2016;80(1):98-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- [Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Part 3. Surgical management of severe traumatic brain injury (options)] Vopr Neirokhir. 2016;80(2):93-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury & Persistent Symptoms. (3rd ed.). Ottawa: Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; 2013. 1–163

- [Google Scholar]

- A consensus-based interpretation of the benchmark evidence from South American trials: treatment of intracranial pressure trial. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(22):1722-1724.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurocritical Care Society; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Consensus summary statement of the International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(9):1189-1209.

- [Google Scholar]

- NICEM consensus on neurological monitoring in acute neurological disease. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(8):1362-1370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical applications of intracranial pressure monitoring in traumatic brain injury: report of the Milan consensus conference. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156(8):1615-1622.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations on the use of EEG monitoring in critically ill patients: consensus statement from the neurointensive care section of the ESICM. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(8):1337-1351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multimodality monitoring consensus statement: monitoring in emerging economies. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(02):S239-S269.

- [Google Scholar]

- The International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: a list of recommendations and additional conclusions: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(02):S282-S296. 2,

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the surgical management of traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(3):1-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- The management of acute neurotrauma in rural and remote locations: A set of guidelines for the care of head and spinal injuries. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6(1):85-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for prehospital management of traumatic brain injury, 2nd edition. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12(01):S1-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, 4th edition. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(1):6-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurocritical Care Society; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Consensus summary statement of the International Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference on Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care : a statement for healthcare professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(9):1189-1209.

- [Google Scholar]

- American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. ACS TQIP best practices in the management of traumatic brain injury. Chicago: American College of Surgeons. Available at: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/tbi_guidelines.ashxReleased January 2015. Accessed November 30, 2018

- Emergency Neurological Life Support: intracranial hypertension and herniation. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23(02):S76-S82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Neurological Life Support: severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27(01):159-169.

- [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Stake A, Devi BI, et al. Traumatic brain injury—multi organizational consensus recommendations for India. 2017;1(78). Available at: http://ntsi.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Version.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2018

- World Health Organization. The WHO Trauma Care Checklist. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencycare/publications/trauma-care-checklist.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2018

- Rubiano AM, Alcala-Cerra G, Moscote-Salazar LR. Trends in management of traumatic brain injury by emergency physicians in Colombia. Panam J Trauma Crit Care Emerg Surg. 2013;2(3):134-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in neurosurgical management of traumatic brain injury in Colombia. Panam J Trauma Crit Care Emerg Surg. 2014;3(1):23-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advanced trauma life support (ATLS): the ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(5):1363-1366.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury, fourth edition. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(1):6-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adherence to guidelines in adult patients with traumatic brain injury: a living systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles County Trauma Consortium. Compliance with evidence-based guidelines and interhospital variation in mortality for patients with severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):965-972.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adherence to brain trauma foundation guidelines for management of traumatic brain injury patients and its effect on outcomes: systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(13):1407-1418.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brain Trauma Foundation guideline compliance: results of a multidisciplinary, international survey. World Neurosurg. 2018;116:e399-e405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guideline adherence and outcomes in severe adult traumatic brain injury for the CHIRAG (Collaborative Head Injury and Guidelines) study. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:169-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cureus. 2014;6(5):e179.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Population. In: United Nations, Handbook of Statistics 2018, Geneva, 2018. Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/tdstat43_en.pdf

- Traumatic brain injury: global collaboration for a global challenge. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(2):136-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Editorial. Research in global neurosurgery: informing the path to achieving neurosurgical equity. J Neurosurg. 2019;130(4):1053-1054.

- [Google Scholar]

- We would like to thank the following individuals for their dedication and contribution to identifying the global neurosurgical deficit. Collaborators are listed in alphabetical order; Executive Summary of the Global Neurosurgery Initiative at the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. Global neurosurgery: the current capacity and deficit in the provision of essential neurosurgical careJ Neurosurg. 2018;•••:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strengthening health systems to provide emergency care.Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. (3rd ed. Chap 13.). Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. In: eds.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential neurosurgical workforce needed to address neurotrauma in low- and middle-income countries. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:295-299.

- [Google Scholar]