Translate this page into:

Quality of life and health of opioid-dependent subjects in India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Mona Srivastava, 36/2 HIG, Kabir Nagar Colony, Durgakund, Varanasi - 221 005, India. E-mail: drmonasrivastava@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The quality of life (QoL) of substance abusers is known to be severely impaired. This study was carried out to assess the impact of opioid dependence on the QoL of subjects and compared it with the normal subjects.

Materials and Methods:

Based on specified inclusion criteria a total of 47 subjects were recruited from a tertiary care center from India. The WHOQoL-BREF scale domain scores obtained at baseline were compared to that of normal subjects. An assessment of dysfunction and reasons for continuing and other parameters were assessed.

Results:

WHOQoL-BREF domains (Physical, Psychological, Social relationships and Environment) showed significantly lower scores and the difference was statistically significant.

Interpretation and Conclusions:

The results showed that QoL is an important parameter in assessment of substance abusers and can be used for long-term prognosis of these individuals.

Keywords

India

opioid users

quality of life-controls

Introduction

Heroin is the most widely consumed illicit opiate in the world. Heroin, cocaine and other drugs kill around 0.2 million people each year (UNODC).[1] Illicit drugs undermine economic and social development and contribute to crime, instability, insecurity and the spread of HIV.[2] Opioids (largely heroin) continue to be the dominant drug type accounting for treatment demand in Asia.[1] Opioid dependence is a cluster of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive phenomena in which the use of opioid takes on a much higher priority for a given individual than other behaviors that once had greater value. A central descriptive characteristic of the dependence syndrome is a strong desire, sometimes overpowering, to take opioid which may or may not have been medically prescribed.[3] It is recognized that the concept of quality of life (QoL) should be applied to the studies on drug dependence in terms of social functioning, physical, and psychological well-being and environment and life satisfaction. QoL evaluation should represent an assessment of the impact of treatment on patient functioning and well-being. The QoL has also been acknowledged as an important tool in the evaluation of drug programs.[45]

Patient-perceived health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has become an important outcome in health care as an indicator of treatment effectiveness. Moreover, studies in opioid-dependent subjects seeking treatment show that very poor HRQoL[678] improves when subjects participate in substitution treatment.[89] The rates of dissatisfaction with life are higher among opioid-dependent persons as compared to the general population.[8] The QOL is severely impaired among substance users[1011] and opioid-dependent subjects.[12] Studies on QoL have recently started to involve the field of drug addiction to go beyond the presence and severity of addiction symptoms and the side effects of treatments by examining how drug-addicted patients perceive and experience the repercussions on their daily life.[13] The nature of heroin dependence makes consideration of QoL, particularly overall QoL, highly relevant. First, addiction to illicit drugs is a cluster of physiological, behavioral, and cognitive phenomena,[14] which can damage individuals’ physical and mental health, role performance, and social adaptation.[1516] In addition, various studies show that heroin use also led to poor QoL in the social domain.[1718] Various factors, such as socio-economic status, localities, gender, educational level, HIV status, dual diagnosis, and personality disorder, were associated with poor QoL among heroin users.[8121718] QoL can be measured by a variety of generic and disease-specific instruments.[16] The World Health Organization Quality of Life scale (WHOQoL and its shorter version WHOQoL-BREF) was developed as cross-cultural tool for intervention studies in health care settings and a Hindi version is available.[19] WHOQoL-BREF is a 26-item shorter version of the WHOQoL-100 which correlates at 0.9 with the WHOQoL-100 with good discriminant validity, content validity and test-retest reliability.[2021]

However, very few studies have evaluated the correlates of QoL in heroin user's and social support. Understanding these correlates may provide a basis to develop intervention strategies to improve the QoL. Thus, the aims of this study were to compare the QoL between subjects with and without heroin use and to examine the association of QoL with socio-demographic characteristics, characteristics of heroin use and social support among heroin users.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The sample comprised two groups of 47 subjects having heroin dependence (HD) and 80 subjects forming normal controls (NC), aged 18-55 years. The patient groups (HD) were recruited from the De-addiction clinic, Department of Psychiatry of Sir Sunder Lal Hospital, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. They were diagnosed according to ICD-10[22] criteria by the consultant psychiatrist. Subjects in active withdrawal state, or having co-morbid psychiatric illnesses and other substance abuse were excluded. Normal control comprised of subjects taken from staff and students of BHU and distant relatives of subjects, included persons whose current psychiatric status was ‘normal’ as indicated by a score of < 3 on the Hindi version of General Health Questionnaire-12.[2324] The study was approved by the ethical committee of the university.

Assessment

Data was collected on the basis of a single cross-sectional assessment interview of the subjects who fulfilled the required inclusion and exclusion criteria and provided written informed consent. All the subjects were administered the socio-demographic proforma, clinical profile sheet, WHOQoL-Brief Hindi version and social support questionnaire (SSQ).[25]

The QoL assessment was made with World Health Organization (WHO)-QoL BREF, Hindi version (WHOQoL-BREF).[19] The questionnaire includes two items on overall QoL and general health, while the remaining 24 items measure four domains of QoL: (i) Physical (7 items); (ii) psychological (6 items); (iii) social relationships (3 items); and (iv) environment (8 items). It enquires about QoL in the ‘last 2 weeks’, and is easily administered. Each item is rated on a 5-point (0-5) scale and the domain scores (within a 0-100 range) are calculated with 100 denoting the highest achievable score. The scale has been reported to be useful for clinics with high patient load as it takes only 5-8 min to complete.[22] A Likert type 5-point scale was used for each question. The fifth choice indicates the best status and the first choice indicate the worst status. A higher score indicates better QoL. The 26-item ‘BREF’ version and the 100-item full version (WHOQoL-100) have a correlation of > 0.89. Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ),[2526] it is an Indian adaptation, in Hindi language, of the Pollack and Harris scale[27] to measure perceived social support. It has 18 items; a higher score indicates more perceived social support. The items in the scale refer to help, concern, support, reinforcement and criticism that a person gets from one's family, friends, social acquaintances and working colleagues. It is a robust instrument in terms of both consistency and stability of scores. It can be used in a variety of situations where the perceived social support is required as an independent, dependent or intervening variable. It has a test-retest reliability of 0.59 and correlation with clinician's assessment at 0.80 and with items of social support from Family Interactions Pattern Scale[28] at 0.65.

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12),[2324] the GHQ-12 is a 12-item self-administered questionnaire used extensively in clinical practice to measure changes in non-psychotic psychiatric status over the past month. There are four possible responses to each question, which were scored 0-0-1-1. A score of ≤3 is the cut-off point for “psychiatric distress”.

Results

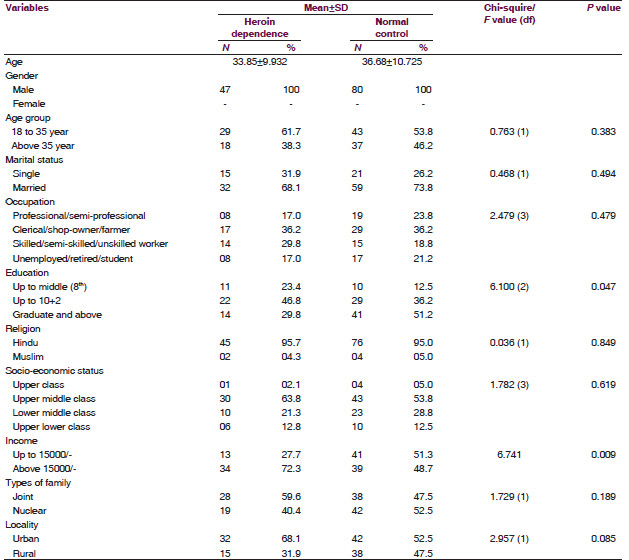

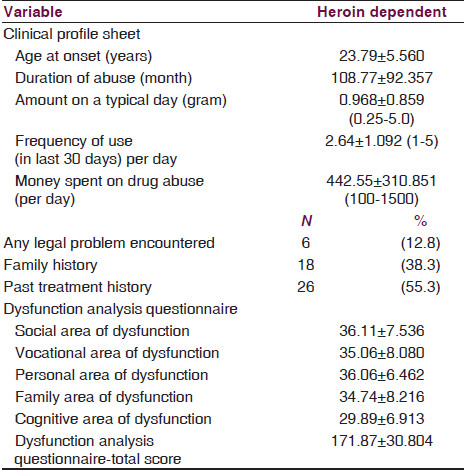

There were two study groups consisting of 47 heroin-dependent (HD) patients and 80 people comprising the normal control group (NC). All subjects were males. The mean ± SD age of heroin-dependent patients was 33.85 ± 9.932 years and 36.68 ± 10.725 for the NC group. A majority (61.7%) of heroin-dependent patients were below 35 years of age and 68.1% were married. Clerical/shop-owner/farmer and skilled/semi-skilled/unskilled worker comprised the main occupation group 36.2% and 29.8%, respectively. Most were educated above matriculation, earned above Rs. 15000 per month. 95.7% belonged to Hindu religion, were from upper middle class (63.8%), joint families (59.6%) urban background (68.1%). The mean ± SD age at onset for heroin-dependent patients was 23.79 ± 5.560 years, duration of abuse 108.77 ± 92.357 months, intake on a day 0.968 ± 0.859 (range 0.25-5.00) grams of heroin, frequency of use 2.64 ± 1.092 (range 1-5) times and money spent on drug Rs. 442.55 ± 310.85 (range 100-1500) in a day. 55.3% had sought treatment in the past and 12.5% had encountered a legal problem. 38.3% of the subjects in the experimental group had a positive family history [Tables 1 and 2].

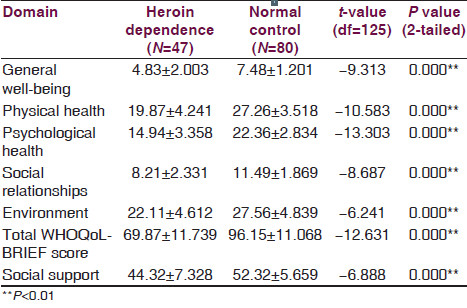

There were significant differences in the WHOQoL-BREF domain scores between the heroin-dependent group and the normal control group in all the four domain, wherein the scores were lower in the heroin-dependent subjects than normal control (i.e. the QoL of heroin-dependent groups was significantly lower than the normal controls). T-test carried out across the two groups yielded the following value: ‘physical health’ (t = -10.583, df = 125, P < 0.001); ‘psychological health’ (t = -13.303, P < 0.001); ‘environment’ (P = -6.241, P < 0.001); ‘social relationships’ (t = -8.687, P < 0.001) and total score (t = -12.631, P < 0.001) [Table 3].

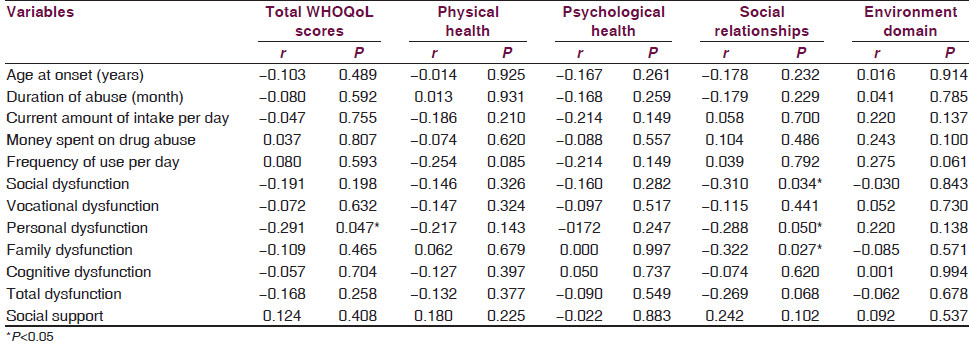

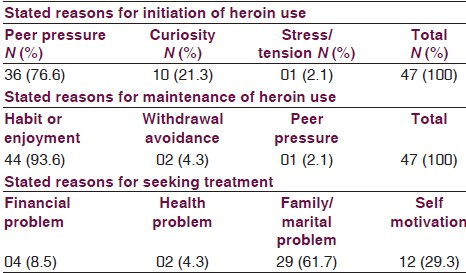

Significant negative correlation were found between the income group and ‘environment domain’ (t = -2.240, df = 45, P = 0.030). A significant positive correlation was found between the type of family and ’social relationship domain’ (t = 2.573, df = 45, P = 0.013) and WHOQoL total scores (t = 2.593, df = 45, P = 0.013). Positive correlation between the religion and WHOQoL total scores (t = 2.088, df = 45, P = 0.042) and environment domain (t = 2.710, df = 45, P = 0.009) and also between localities and ‘social relationship’ domain (t = 2.428, df = 45, P = 0.019). Socio-economic status groups show significant (F = 3.786, df = 3, P = 0.017) correlation with ‘psychological health domain’ of QoL. There was no significant correlation between any of the WHOQoL scores and the following variables: age at onset, duration of drug (heroin) abuse, current amount of intake (per day), money spent on drug abuse, frequency of the use (per day) and social support [Table 4]. The variables associated with the heroin dependence revealed that peer pressure was the most common reason for starting the use of heroin (76%). Most patients perceived heroin use as being continued as a result of force of habit or due to the enjoyment derived from it (93%). The most common reason for seeking treatment was family/marital complications (30%). This was followed by self motivation, financial complications and health-related consequences [Table 5].

Discussion

Our study was carried out to assess the various aspects of QoL in heroin dependent subjects in comparison to the normal controls, and to examine the relationship between the socio-demographic and clinical correlates of QoL of heroin-dependent subjects and their social support. The results showed that heroin-dependent subjects had poorer QoL than normal controls in the general well-being items, physical, psychological, environmental and social relationship domains and total WHOQoL scores. Previous studies have also shown that heroin users had poorer QoL than nonusers in the various domains of WHOQoL-BRIEF.[293] This is consistent with findings of Smith and Larson[30] and Koch.[31] The findings of our study have also been supported by the results of studies done by Bizzarri.[17]

The mean ± SD age of heroin-dependent patients was 33.85 ± 9.932 years that was comparable to the mean age of opioid-dependent patients (35.3 ± 10.0) assessed for QoL by Dhawan and Chopra[32] and Bizzari et al.[17] Majority of the subjects were married (68.1%) comparable with earlier study by Dhawan and Chopra[32] where 53.7% were married. Considering the other socio-demographic variable, we found a higher educational level, better employment rate, higher income group and upper middle socio economic status in heroin-dependent subjects. This finding is contrary to that of previous studies.[172932] This could be because of the study setting, which was clinic based and hence could have contributed to better awareness in the walk in kind of a set up of the present study, in contrast to the community and specialized treatment settings in the other three studies. Studies have shown that the QoL improves with the substitution treatment;[32] we however did not look into the treatment aspect.

The social support in heroin-dependent subjects in comparison to normal controls was significantly low. Different studies[3334] suggest the poor social support can effect QoL. It is important to note that the perceived social support from family, friends and other recovering drug users can play a vital role in preventing/delaying relapse[3334] and abstinence from drug, in other words, improved QoL. Our findings also echo the same as the opioid-dependent subjects had a poor social support along with a poor QoL. Hence, enhancement of social support is an important strategy for improving the QoL in heroin-dependent subjects. The assessment of the various factors related to heroin abuse shows that the primary reason for initiation of the abuser is peer pressure (76%), and maintenance is because of the enjoyment aspect and withdrawal effects (93%). The main reason for seeking treatment is because of the family pressure (30%). These findings have been found to be similar to the other studies;[512] these parameters can be made use of in spreading awareness and involving the community in the prevention issues. Family and peer group can be positively used toward fostering a positive living and forming a good social support basis so as to maintain the abstinent state.[35]

The results of the present study need to be interpreted keeping its limitations in mind. First, the small sample size, purposive sampling could yield type II errors. Intake of subjects from a single treatment center could cause bias and difficulty in generalizing the results. Secondly, the results of this clinic-based study cannot be extrapolated to the community. Furthermore, we would like to suggest that future studies with a larger and diverse sample along with a pre post intervention program are needed to make robust conclusions. Our study indicates that heroin-dependent subjects experience a lower QoL and a poor social support when compared with the normal controls.

Acknowledgment

All the subjects and their families who participated in the study.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Associations of clinical parameters with health-related quality of life in hospitalized persons with HIV disease. AIDS Care. 1999;11:71-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- ITINERE Investigators. Gender differences in health related quality of life of young heroin users. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:145.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life among opiate-dependent individuals: A review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:364-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical correlates of health-related quality of life among opioid-dependent patients. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1205-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- The addiction severity index medical and psychiatric composite scores measure similar domains as the SF-36 in substance-dependent veterans: Concurrent and discriminant validity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:165-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-perceived health among Canadian opiate users: A comparison to the general population and to other chronic disease populations. Can J Public Health. 2004;95:99-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of heroin addicts entering methadone maintenance treatment: Quality of life and gender. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:1353-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance treatment in an ambulant setting: A health-related quality of life assessment. Addiction. 2003;98:693-702.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health care technology assessment and health related quality of life. In: Banta HD, Luce BR, eds. Health Care Technology and Its Assessment: An International Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. p. :114-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- A sociological perspective on health related quality of life research. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, eds. Advances in Medical Sociology, Quality of Life in Health Care. London, UK: Jai Press; 1994. p. :1-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and personality disorders in heroin abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:73-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations on health-related quality of life research to support labelling and promotional claims in the United States. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:887-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outpatient methadone maintenance treatment program. Quality of life and health of opioid-dependent persons in Lithuania. Medicina (Kaunas). 2007;43:235-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Earlier marijuana use and later problem behavior in Colombian youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:485-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- The consequences in young adulthood of adolescent drug involvement. An overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:746-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dual diagnosis and quality of life in patients in treatment for opioid dependence. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:1765-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life activities and life quality of heroin addicts in and out of methadone treatment. Int J Addict. 1993;28:211-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL-Hindi: A questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care setting in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India. 1998;11:160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL-Brief, Field Trial Version. In: Programme on mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ICD-10 classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders. In: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1972.

- [Google Scholar]

- A user's guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson; 1988.

- Standardisation of hindi version of goldbergs general health questionnaire. Indian J Psychiatry. 1987;29:63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a scale for assessment of social support: Initial tryout in Indian setting. Indian J Social Psychiatry. 1987;4:353-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manual for PGI social support questionnaire. Varanasi: India Rupa Psychological Centre; 1998.

- Validation of family interaction patterns scale. Indian J Psychiatry. 1986;28:211-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and its correlates among heroin users in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:177-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life assessments by adult substance abusers receiving publicly funded treatment in Massachusetts. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:323-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life quality vs the ‘quality of life’: Assumptions underlying prospective quality of life instruments in health care planning. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:419-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does buprenorphine maintenance improve the quality of life of opioid users? Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:130-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social and cognitive approach in relapse prevention. Bengal J Psychiatry. 2001;10:79-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Personality, stress, and social support in cocaine relapse prediction. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:77-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social support in treatment-seeking heroin-dependent and alcohol dependent patients. Indian J Med Sci. 2002;56:602-6.

- [Google Scholar]