Translate this page into:

Paradoxical Brain Herniation after Cranioplasty: Secondary Sunken Flap Syndrome

Archit Latawa, MCh Department of Neurosurgery, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research Chandigarh 160012, Chandigarh India dr.archit@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Decompressive craniectomy is a life-saving procedure done for innumerable etiologies. Though, not a technically demanding procedure, it has its own complications. Among many, sinking flap syndrome or syndrome of the trephined or paradoxical herniation of brain is frequently underestimated. It results from the pressure difference between the atmospheric pressure and the intracranial pressure causing the brain to shift inward at the craniectomy site. This can present with either nonspecific symptoms leading to delay in diagnosis or acute neurological deterioration, memory disturbances, weakness, confusion, lethargy, and sometimes death if not treated. Cranioplasty is a time validated procedure used to treat paradoxical brain herniation with good and early neurological recovery. We, here in, are going to describe a case report in which the paradoxical herniation occurred after cranioplasty which has not been described in literature.

Keywords

central nervous system

headache

paradoxical

brain herniation

secondary sunken flap syndrome

Introduction

Grant and Norcross in 1939 first described the syndrome of trephined or paradoxical herniation of brain.1 It is one of the rarest complications of decompressive craniectomy and is generally underreported.2 The word “paradoxical” denotes two paradoxical phenomena. First, herniation of the decompressed side of the brain and, second, the treatment is also paradoxical, as it is exactly the opposite of what we do in herniations.3 Its clinical presentation has a variable spectrum starting from nonspecific symptoms at one end and motor weakness, memory disturbances, confusion, lethargy, and death at the other end.4 Its pathophysiology is poorly understood and is mainly relied on the pressure differences between the atmosphere and the brain and the changes in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow dynamics.5 Diagnosis is made both clinically and radiologically with the most important factor being the shape of the craniectomy site which gets curved inside.4 Cranioplasty is a documented procedure that helps in early recovery with complete reversal of neurological deficits.6 We want to discuss our case as the sinking flap syndrome (SFS) occurred after cranioplasty which is probably the first case ever described.

Case Report

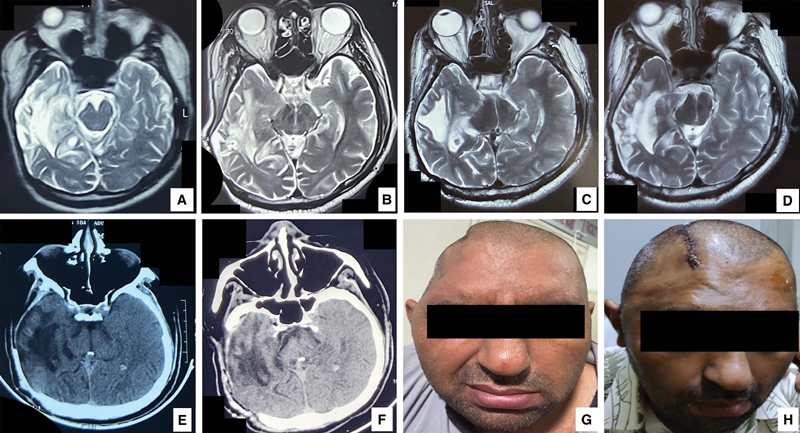

A 38-year-old male with history of road traffic accident presented to our trauma center with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of E2V2M5. After initial resuscitation, his noncontrast computed tomography (NCCT) head showed right frontotemporo-parietal acute subdural hematoma (SDH) with underlying contusion with mass effect and midline shift. Patient underwent right decompressive craniectomy with evacuation of acute SDH and the bone flap was not placed back due to underlying edema. Patient was discharged in satisfactory condition with GCS of E4V5M6 after 10 days. Patient underwent autologous bone flap cranioplasty after 3 months which was again uneventful. After 3 years, patients started complaining of weakness on left side of the body, decreased verbal output, memory loss, and confusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done and it was compared with older MRI done 2 years back. Serial MRI showed progressive uncal herniation suggestive of sunken flap syndrome (Fig. 1 A–D). Patient underwent bone flap removal surgery with lax duraplasty in the emergency setting. Immediate NCCT head showed decreased uncal herniation and the weakness on left side was also improved. He was discharged after 5 days with GCS E4V5M6. Further plan is do mesh cranioplasty with an aim for complete coverage of the defect.

-

Fig. 1 (A–D) Showing progressive uncal herniation on right side. (E and F) Showing relief of mass effect and opening of basal cisterns after decompressive craniectomy and lax duraplasty. (G) Clinical photograph showing sunken flap preoperatively. (H) Clinical photograph showing normal contour of the scalp after decompressive craniectomy and lax duraplasty.

Fig. 1 (A–D) Showing progressive uncal herniation on right side. (E and F) Showing relief of mass effect and opening of basal cisterns after decompressive craniectomy and lax duraplasty. (G) Clinical photograph showing sunken flap preoperatively. (H) Clinical photograph showing normal contour of the scalp after decompressive craniectomy and lax duraplasty.

Discussion

Decompressive craniectomy is done to relieve the mass effect, so that intracranial pressure (ICP) can be lowered.7 One of the first surgeries, which a neurosurgery resident learns, is still associated with many complications. SFS is one of the most interesting complication of decompressive craniectomy.8 It can occur any time after the surgery but is generally associated with some CSF drainage procedures (lumbar puncture and shunt procedure) in the postoperative period as the drainage of the CSF disturbs the equilibrium between the atmospheric (1,033 cm of water) and CSF pressure (15 cm of water), thus causing the increased atmospheric pressure to cause inward indentation of the craniectomy flap and results in SFS.9

The pathophysiology is explained by two mechanisms. First, after the decompressive craniectomy, the bony interface between the atmosphere and the intracranial contents is lost. Now the atmospheric pressure can directly act on the cranium. Normally the ICP is negative, once the bone is removed, the ICP tends to equalize with atmospheric pressure, and thus there is increase in ICP which has been documented with CT perfusion studies in literature.10 Due to the pressure difference between the atmospheric pressure and the ICP, the craniectomy site curves inward causing a mass effect. This is a paradoxical phenomenon because the already decompressed side of the brain starts herniating and causes mass effect. Second, the altered CSF flow dynamics (low flow) after the initial brain injury and decompressive craniectomy leads to trans ependymal egress of CSF leading to lowering of ICP and thus resulting in SFS.11 12

Clinically, the patients present either with sudden onset motor weakness, decreased verbal output, memory disturbances, confusion, and even death if left untreated, or they may just present as a plateau in an otherwise improving patient or the symptoms can altogether be nonspecific leading to diagnostic delay. So clinical suspicion is of utmost important to diagnose this entity.4

Diagnosis is generally made clinically by looking at the concave skin flap at the craniectomy site and the MRI/CT scan showing mass effect. The second paradoxical thing about SFS lies in its treatment part which is exactly the opposite of what we do normally in other herniations. In patients presenting acutely, the head end is kept down to buy time before cranioplasty which is opposite to other scenarios where head end is kept up to lower ICP.3 Cranioplasty is the time validated method to correct the abnormalities caused by the SFS.6

In our case, SFS occurred after cranioplasty which is not the usual scenario. One possible explanation is incomplete coverage of the brain with the autologous bone used. The remaining exposed portion of brain was under direct atmospheric pressure, thus leading to delayed SFS. But, had this being the reason alone, then the patient should not have improved after removing the bone flap. Another plausible explanation for the same could be the dural thickening and scarring as a result of first surgery, resulting in shrinkage of dura and associated dense adhesions to underlying brain causing the mass effect and being augmented by atmospheric pressure at the site of craniectomy defect. So, in the emergency setting, the bone flap was removed and dura was opened and lax duraplasty was done to relieve the mass effect and patient was further planned for mesh cranioplasty for better coverage of the craniectomy defect.

Conclusion

SFS can be primary (after the craniectomy) and secondary (after cranioplasty). Secondary SFS is due to the inadequate coverage by cranioplasty and dural thickening and scarring being the contributory factors. Both are the result of pressure differences between the atmosphere and the ICP, though similar in presentation but the treatment is different. Cranioplasty for primary SFS and bone flap removal with lax duraplasty followed by definitive cranioplasty for secondary SFS appears to be a viable option.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Sinking skin flap syndrome in the multi-trauma patient: a paradoxical management to TBI post craniectomy. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020(6):a172.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sinking flap syndrome revisited: the who, when and why. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43(1):323-335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of early cranioplasty in reversing the “syndrome of the trephine/motor trephine syndrome/sinking skin flap syndrome”. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(3):666-673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decompressive craniectomy in acute brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol. 2017;140:299-318.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of possible complications in patients after decompressive craniectomy. Rozhl Chir. 2020;99(1):5-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sinking skin flaps, paradoxical herniation, and external brain tamponade: a review of decompressive craniectomy management. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9(2):269-276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological improvement after cranioplasty. Analysis by dynamic CT scan. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;122:49-53. (1,2):

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-cranioplasty cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamic changes: magnetic resonance imaging quantitative analysis. Neurol Res. 1997;19(3):311-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible monoparesis following decompressive hemicraniectomy for traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(2):245-254.

- [Google Scholar]