Translate this page into:

Improvement of gaze palsy and dizziness caused by vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia by conservative approach: A case report

*Corresponding author: Hanik Badriyah Hidayati, Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. hanikhidayati@fk.unair.ac.id

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Nuryanto H, Hidayati HB. Improvement of gaze palsy and dizziness caused by vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia by conservative approach: A case report. J Neurosci Rural Pract. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_436_2024

Abstract

Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (VBD) is a rare case with incidence <0.05–0.06%. With prevalence ranges from 0.2% to 4.4%, its etiology is still unclear. We reported a case of a 62-year-old male brought to the hospital with complaints of sudden dizziness in the past 4 days before admission. Complaints were accompanied by binocular diplopia and a thick sensation on the tongue. There was no significant history of previous illness. The patient was prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy (100 mg of aspirin daily and 75 mg of clopidogrel daily) for 90 days, followed by continued single-antiplatelet therapy (100 mg of aspirin daily). After 5 days of treatment, the patient was discharged due to improved dizziness complaints. This case shows a conservative approach, blood pressure management, and stroke prevention, which could be considered as an initial treatment for VBD.

Keywords

Antiplatelet

Dolichoectasia

Gaze palsy

Vertebrobasilar

INTRODUCTION

Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (VBD) is a rare condition with an incidence <0.05–0.06%. With prevalence ranging from 0.2% to 4.4%, the etiology of VBD remains uncertain. Risk factors of VBD include older age, male sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, smoking, and a history of myocardial infarction.[1-7] The clinical manifestations of VBD are diverse, ranging from cranial nerve involvement symptoms [e.g., hemifacial spasm (HFS), tinnitus, trigeminal neuralgia, ophthalmoplegia, and nystagmus] to headache, hemiparesis, parenthesis, dementia, ataxia, and even seizure.[1-4] Surgical intervention of microvascular decompression has been identified as a potential treatment to relieve the symptoms. Recent studies have demonstrated improvements in patient’s symptoms. The following case report adds more evidence of an improvement in a VBD case with clear symptoms of dizziness accompanied by gaze palsy in VBD, managed noninvasively.

CASE REPORT

Male, 62-year-old, was brought to the hospital with complaints of sudden dizziness [dizziness assessment rating scale (DARS) = 6; Amer Dizziness Diagnostic Scale = 7] in the past 4 days before admission. Complaints were accompanied by binocular diplopia and a thick sensation on the tongue. There was no significant history of previous illness. The patient was an active smoker for approximately 10 years with a consumption of 1 pack/day.

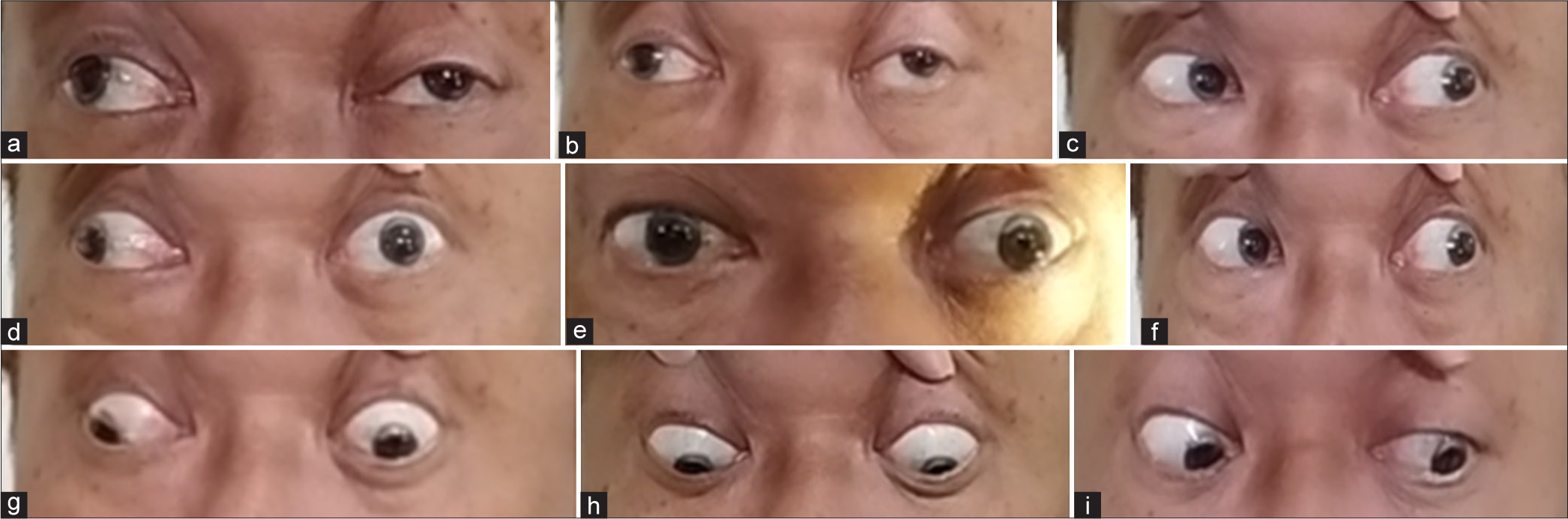

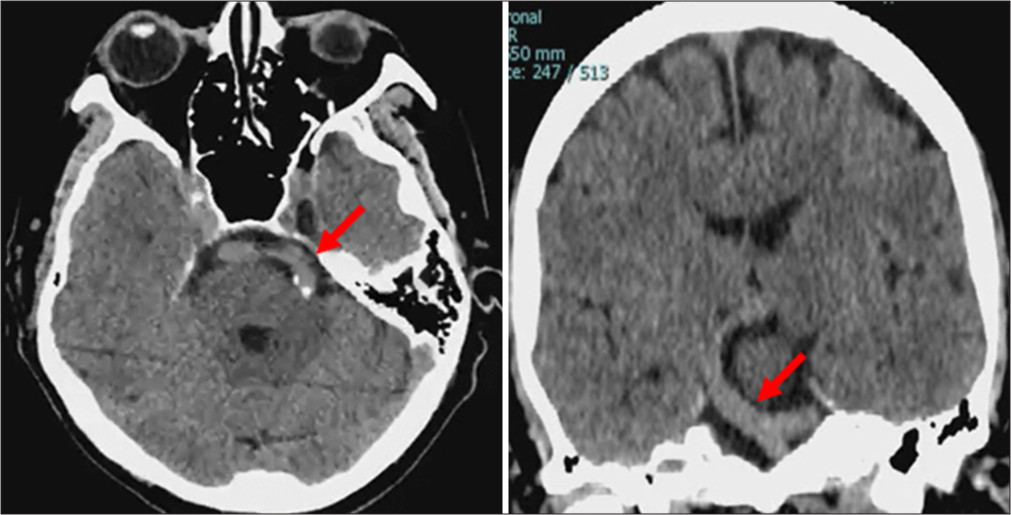

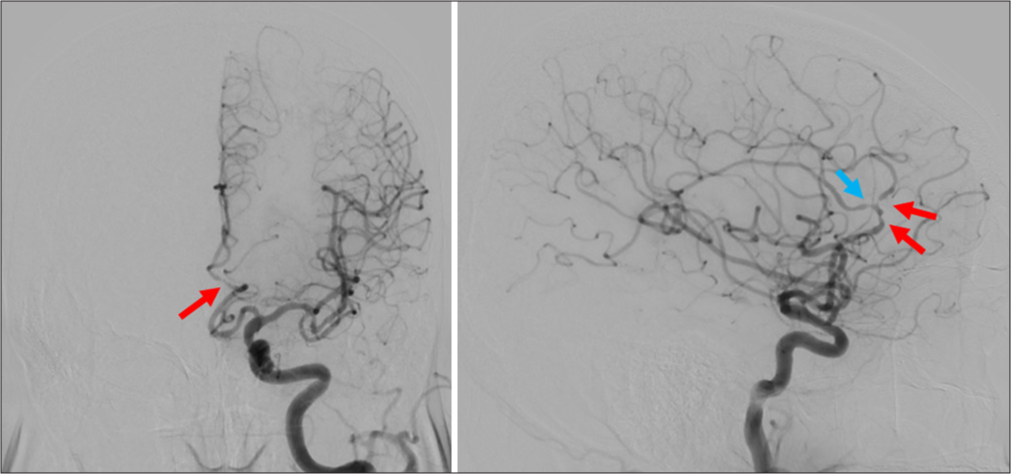

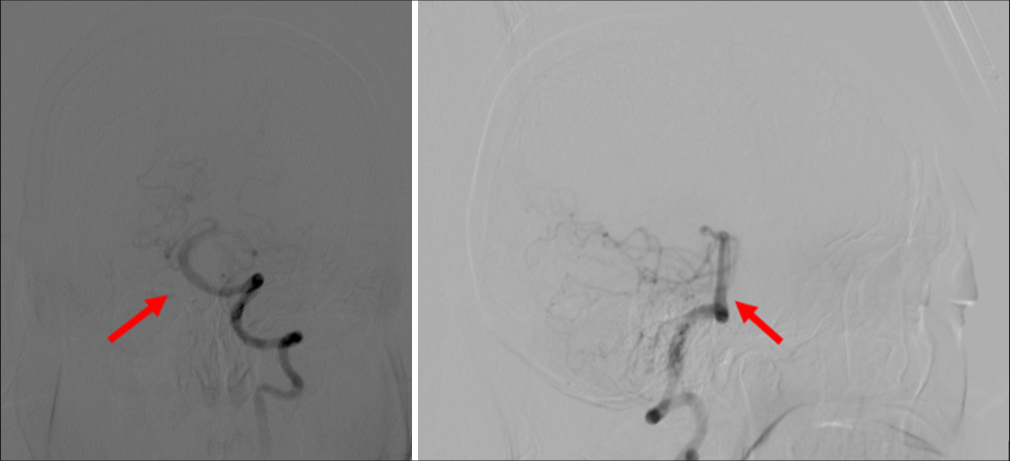

Neurological examination revealed 3rd and 4th cranial nerve palsy of the left eye and right lingual palsy upper motor neuron type [Figure 1]. Basic laboratory results were only significant for hypokalemia (3.1 mmol/L). Head computed tomography (CT) scan imaging examination without contrast found arteriosclerosis with dolichoectasia of the basilar artery [Figure 2]. This finding was confirmed by cerebral angiography, which showed vertebrobasilar artery dolichoectasia, moderate stenosis in the proximal callosomarginal artery and distal left A2, and mild stenosis in the proximal segment of left A3 [Figures 3 and 4].

- Ophthalmoplegia with involvement of left cranial nerve IV and partial cranial nerve III. (a-d,g) Left eye unable to gaze upward, medial, and medio-downward. (e) Frontal gaze showed the left eye slightly pulled to the lateral due to partial paralysis of the left cranial nerve III. (f) Patient still had normal left gaze. (h,i) Still able to gaze downward and latero-downward.

- Non-contrast head computed tomography scan showed atherosclerosis with dolichoectasia of the basilar artery (red arrows).

- Cerebral angiography: Moderate stenosis in proximal callosomarginal artery and distal left A2 (red) and mild stenosis in the proximal segment of left A3 (blue).

- Cerebral angiography: Vertebrobasilar artery dolichoectasia (arrows).

The patient was prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy (100 mg of aspirin daily and 75 mg of clopidogrel daily) for 90 days, followed by continued single-antiplatelet therapy (100 mg of aspirin daily). No interventional management was performed regarding dolichoectasia or stenosis in the patient. After 5 days of treatment, the patient was discharged due to improved dizziness complaints. Follow-up 5 months later, the patient’s complaints of spinning dizziness and double vision were no longer present (DARS = 1). There were no obstacles to eyeball movement [Figure 5].

- Improvement of left ophthalmoplegia after 5 months.

DISCUSSION

VBD is a term derived from the Greek language, where “dolichos” means “elongation” and “ectasia” means “dilatation.” It is a rare progressive arteriopathy primarily affecting intracranial posterior circulation, specifically the vertebrobasilar artery. It is important to differentiate between VBD and basilar dolichoectasia as they can present differently, different radiological features, and potentially result in different complications. The diagnosis of VBD is made radiologically with a basilar artery diameter at the midpons measured >4.5 mm, indicating dolichoectasia.[1] The diameter cutoffs for the vertebral artery ≥4 mm to denote ectasia. With prevalence ranging from 0.2% to 4.4%, the etiology of VBD remains uncertain. Old age, the male sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, smoking, and a history of myocardial infarction have been proposed to be risk factors for VBD.[1-7]

The clinical manifestation of VBD can vary widely, from cranial nerve involvement symptoms (e.g., HFS, tinnitus, trigeminal neuralgia, ophthalmoplegia, and nystagmus) to headache, hemiparesis, paresis, parenthesis, dementia, ataxia, and even seizure. The underlying vascular mechanism leading to alteration in blood flow within the vertebrobasilar system results in decreased cerebral perfusion of posterior circulation territory due to limited space within the posterior fossa.[3] The trigeminal and facial nerves are particularly susceptible to involvement. Abducens nerve palsy resulting from VBD-related compression is rare, and multiple cranial nerve involvement in VBD cases is infrequently reported. For example, Madhugiri et al. described a case where the patient experienced diplopia due to a left abduction deficit, along with ipsilateral facial pain and muscle twitches.[6] These symptoms were attributed to compression of the abducens, trigeminal, and facial nerves by VBD. Pham et al. reported a similar case, where VBD causes both abducens and ipsilateral trigeminal nerve palsies.[7]

The diagnostic criteria for VBD have not been standardized and usually can be diagnosed incidentally during CT scans, cerebral angiography, or even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[2,8] Historically, autopsy findings were the main source of information on this condition. However, advancements in multimodal diagnostic imaging (such as CT/CT angiography, MRI/magnetic resonance angiography, and catheter-based angiography) have greatly improved our ability to diagnose VBD in living patients. The pathophysiology is typically attributed to the compression or indentation of nerve roots as they traverse the basal cisterns near their entry zone.

The mortality rate associated with VBD is 63% with a range of 1 month to 17 years. Common complications include ischemic stroke (17.6%), brain stem compression (10.3%), and transient ischemic attack (10.1%).[9,10] In some cases, surgical intervention involving microvascular decompression can be a solution to relieve the symptoms, though the evidence base remains constrained.[5] However, most reported cases have been managed conservatively with an emphasis on blood pressure control due to perceived risks associated with surgery. Supit et al. have documented the efficacy of blood pressure management in patients with clinical symptoms of HFS with VBD.[5] Furthermore, Sari et al. reported a significant improvement in stroke patients with VBD treated with IV thrombolysis. These results were also backed up with previous studies that reported no recurrence of ischemic stroke in VBD patients treated with antiplatelet.[4] Noted a pursuit in the controlled vascular risk factors must be optimized, as the use of antiplatelets or anticoagulants was associated with a 3 times greater chance of hemorrhagic stroke.[3]

CONCLUSION

Patients with dizziness and gaze palsy symptoms on VBD should be considered for neurovascular contact on the cranial nerve. The diagnosis can be incidental when the head CT is performed and should be confirmed by cerebral angiography or even MRI. However, an initial conservative approach is recommended before a surgical approach with comparable outcomes. Blood pressure management and antiplatelets or anticoagulants are the cornerstone in managing patients with VBD. Moreover, a high-resolution head MRI is useful to identify the neurovascular contact.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia as a rare cause of simultaneous abducens and vestibulocochlear nerve symptoms: A case report and literature review. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:523-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertebrobasilar and basilar dolichoectasia causing audio-vestibular manifestations: A case series with a brief literature review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1750.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: Case report and management review in an underappreciated cause of bulbar palsy, weakness, and ataxia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2024;51:458-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intravenous thrombolysis in patient with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia and antiplatelet medication. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:3355-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conservative treatment in hemifacial spasm due to vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:390-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranial polyneuropathy associated with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:1059-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sixth cranial nerve palsy and ipsilateral trigeminal neuralgia caused by vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2018;10:229-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia with typical radiological features. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e239866.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemifacial spasm due to vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;10:65-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute bilateral ophthalmoplegia due to vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia: A report of two cases. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:1302-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]