Translate this page into:

Ears of the lynx: A neuroradiological totemism

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sahib A, Choudhury C. Ears of the lynx: A neuroradiological totemism. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;15:402-3. doi: 10.25259/JNRP_428_2023

Dear Editor,

A 16-year-old girl presented with progressive spastic quadriparesis and mild intellectual disability since childhood without any cranial, sensory, cerebellar or extrapyramidal features. Her family history was negative. The differential diagnoses include abnormalities involving the brain and/or spinal cord including leukodystrophies such as Krabbe disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, adrenomyeloneuropathy, vitamin B12 and vitamin E deficiency, Dopa-responsive dystonia, cerebral palsy, metabolic diseases such as urea cycle defects, biotinidase defects, and hereditary spastic paraplegia, and, rarely, parainfectious causes such as HIV- and HTLV1-associated myelopathy and demyelinating disorders. Her routine workup was unremarkable.

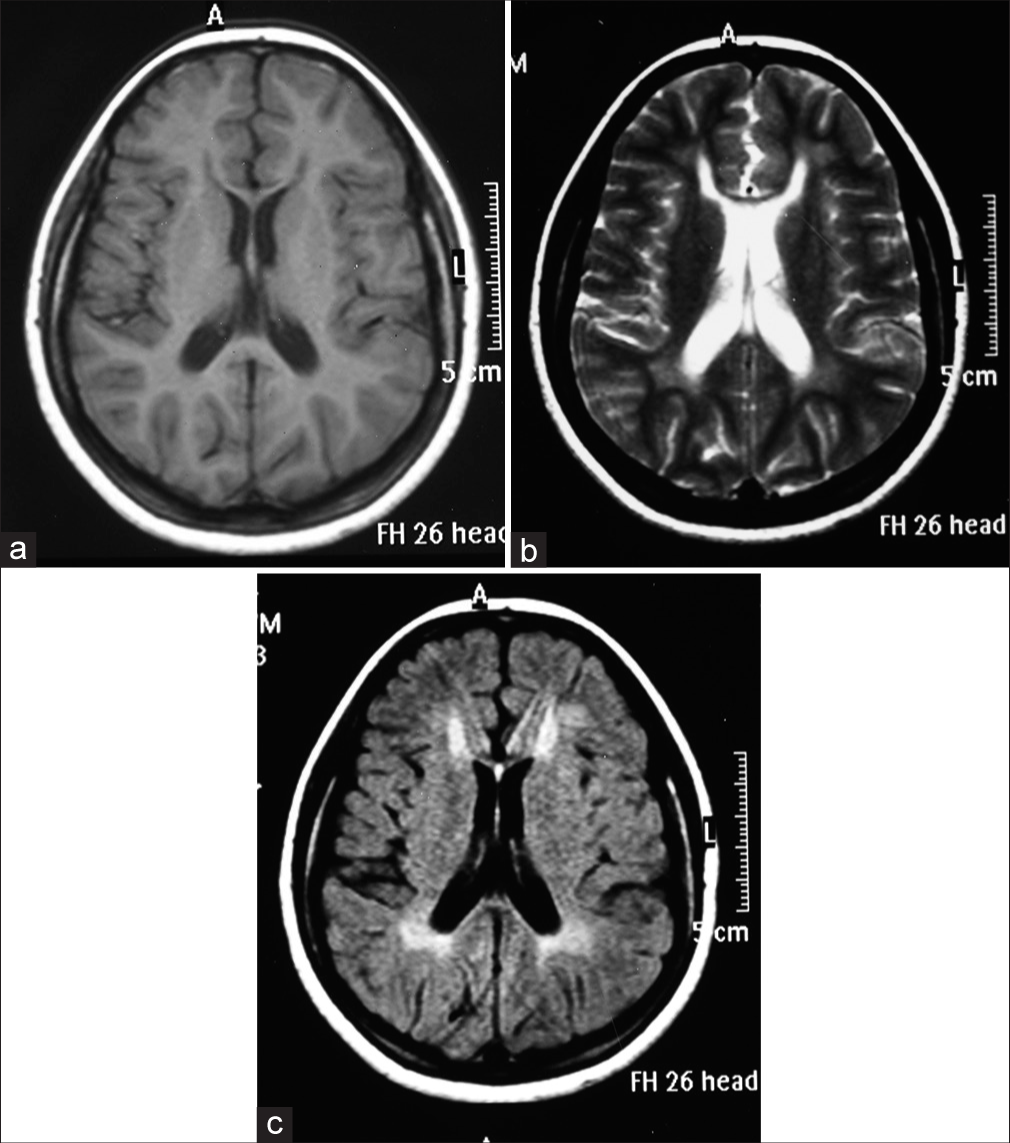

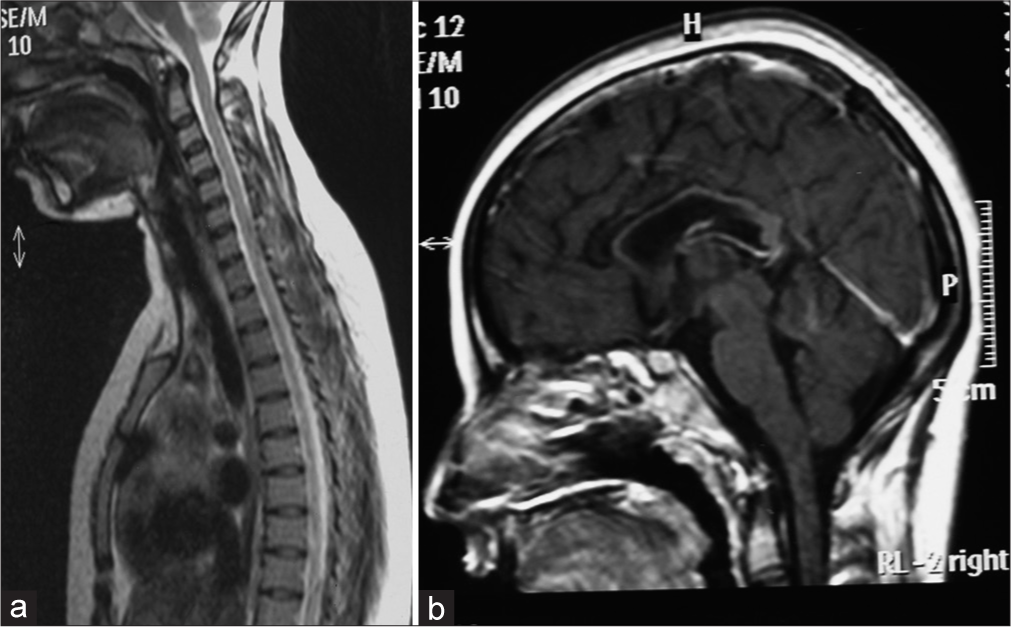

An MRI brain was suggestive of the EARS OF THE LYNX sign [Figures 1a-c]. An MRI spine was suggestive of cervical cord atrophy [Figure 2a]. The MRI brain was also suggestive of corpus callosal thinning [Figure 2b]. A lynx is a wild cat with pointed ears native to North America. This sign is characterized by abnormal T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery conical hyperintensities at the tips of the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles in the region of forceps minor of corpus callosum resembling the tufts of hair over the ears of this wild cat.[1] This finding is usually seen in a subtype of hereditary spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum designated as SPG11 and less commonly in SPG15.[1-3] The SPG11 gene present on chromosome 5 encodes Spatacsin and SPG15 encodes Spastizin, respectively.[1,4] Very rarely, this sign may also be found in patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Marchiafa va-Bignami Syndrome. The presence of this classical MRI finding in a sporadic case could be very useful for targeted genetic testing.

- (a) T1 axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showing hypointensity at the tips of bilateral frontal horn of lateral ventricles in the region of forceps minor, (b) T2 axial MRI brain with hyperintensity at the tip of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricles in the region of forceps minor, and (c) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial MRI brain with hyperintensity at the tip of the frontal horn of the lateral ventricles in the region of forceps minor.

- (a) T2 sagittal section showing cervical cord atrophy and (b) T1 sagittal section showing thin corpus callosum.

Hereditary spastic paraplegia is one of the important differentials for chronic progressive spastic paraparesis or quadriparesis. It could be early or late onset, uncomplicated or complicated with multi-axial involvement in the form of ataxia, seizures, intellectual disability, peripheral neuropathy or extrapyramidal features. There are more than 80 genetic variants detected till now.[5] The mode of inheritance can be autosomal dominant, recessive or X-linked. The list is progressively increasing. The MRI signatures of specific subtypes might help in delineating the subvariant of hereditary spastic paraplegia.[4] This sign has shown to have a high sensitivity ranging from 78.8% to 97% and specificity from 90.9% to 100%.[1] A trial of L-dopa was also given to our patient, but no benefit was noted. The patient was treated with physiotherapy, baclofen with dose optimization along with Botox therapy for spasticity. After reviewing the MRI findings, genetic counseling was offered to the family. On genetic testing, the patient was detected with a compound heterozygous pathogenic variant of SPG11 at exon 15 and 36, respectively, with frameshift mutation.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent is not required as the patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- “Ears of the Lynx” MRI sign is associated with SPG11 and SPG15 hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Neuroradiol. 2019;40:199-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective neuroimaging study in hereditary spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1556-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forceps minor region signal abnormality “ears of the lynx”: An early MRI finding in spastic paraparesis with thin corpus callosum and mutations in the spatacsin gene (SPG11) on chromosome 15. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:52-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging findings in autosomal recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:936-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hereditary spastic paraplegia overview In: GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 2021.

- [Google Scholar]