Translate this page into:

Does education plays a role in meeting the human rights needs of Indian women with mental illness?

Address for correspondence: Mrs. Vijayalakshmi Poreddi, College of Nursing, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Institute of National Importance, Bangalore - 560 029, Karnataka, India. E-mail: pvijayalakshmireddy@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Globally women are one of the vulnerable populations and women without education and with mental illness are doubly disadvantaged.

Aim:

To find out the role of education in meeting the human rights needs of women with mental illness at family and community levels.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive design was carried out among randomly selected recovered women (N = 100) with mental illness at a tertiary care center. Data was collected through face-to-face interview using a structured questionnaire.

Results:

Our findings revealed that human rights needs in physical needs dimension, i.e. access to safe drinking water (χ2 = 7.447, P < 0.059) and serving in the same utensils (χ2 = 10.866, P < 0.012), were rated higher in women with illiteracy. The human rights needs in emotional dimension, i.e. afraid of family members (χ2 = 13.266, P < 0.004), not involved in making decisions regarding family matters (χ2 = 21.133, P < 0.00) and called with filthy nicknames (χ2 = 8.334, P < 0.040), were rated higher in literate women. The human rights needs in religious needs dimension, i.e. allowed to go to temple, church, mosque etc. (χ2 = 9.459, P < 0.024), were not satisfied by the illiterate women. Similarly, literate women felt that they were discriminated by community members due to their illness (χ2 = 9.823, P < 0.044).

Conclusion:

The findings of the present study suggested that women without education were more deprived of human rights needs than literate women. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve literacy of women and to strengthen the legal framework to protect the rights of the women with mental illness.

Keywords

Human rights

illiteracy

literacy

mental illness

needs assessment

women

Introduction

Human rights provide a very important means of protection for people living with mental health problems.[1] Globally, people with mental illness frequently encounter stigma, prejudice, and discrimination from every corner of the community. The situation can be much worse in case of woman.[2] Furthermore, many obstacles to the realization of women's human rights in India are social, cultural in nature and deeply rooted in the traditions of its communities. Issues of female infanticide, rape, dowry harassment, discrimination, and denial of their basic rights continue to be grave issues in Indian society, and all of these carry immense implications for the mental health of women.[3]

Women's rights are grounded first in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and India is one among the countries those are signatory. India also ratified other international conventions specifically banning discriminations against women, such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women[4] and the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.[5] In addition, at national level, India also has a Mental Health Act and the Persons with Disability (PWD) Act, which provide for treatment, protection against human rights abuses, and equal opportunities for the mentally ill. On the other hand, people with mental disorders around the world are exposed to a wide range of human rights violations in the areas of employment, health, education and housing. Many are denied basic human rights such as the right to vote, to marry and to have children.[6] The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare estimates that 6-7% of India's population suffers from mental disorders and about 25% of people with mental illness are homeless.[7] Another area of concern is in India, there is no reliable data on the number of women suffering from mental ailments. Community surveys, from the 1970s to the 1990s, have recorded a greater female morbidity.[8]

Education has been recognized not only as a right in itself but also as a mechanism for the pursuit of other human rights. Literacy enables a person to think rationally, to be understanding, to be more responsible, demand for protection and to make own decisions. On the contrary, illiteracy is the mother of all issues as it gives birth to many other issues like poverty, unemployment and delay in help-seeking behavior. While the constitution of India provides free and compulsory primary education, actual delivery remains patchy. India has 35% of the world's total illiterates and has been ranked 105th in the Global Monitoring Report (GMR), 2008.[9] People with mental illness experience a lot of stigma and discrimination and those with illiteracy and mental illness are double discriminated.[10] Mental illness and illiteracy can contribute toward staggering economic and social costs. In developing countries, up to 90% of people with psychiatric disabilities live with their families.[11] The extent of family support for people with psychiatric disabilities has often been cited as a major factor in the rehabilitation process[1213] and family environment serves as a protective factor in recovery of people with mental illness.

Currently, research that examined human rights violations among illiterate women with mental illness is limited from India. Thus, the present study was aimed to investigate the role of education in meeting the human rights needs of women with mental illness at family and community level. The present study defines illiteracy as the inability to identify, understand, interpret, and communicate and we define human rights violations as abuse to right to life, liberty, freedom, education, health and so forth.

Materials and Methods

Design and setting

This was a descriptive study carried out from August to November 2010 among recovered women with mental illness at a tertiary care center.

Study participants were selected through a random sampling method of the database of patients attending the outpatient department of a psychiatric hospital. All these patients had already been seen in detail by a junior resident, senior resident, and consultant. They also had a detailed medical chart of their history, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome on each follow-up. Those who met the inclusion criteria were interviewed. The study criteria were recovered women with mental illness with a diagnosis of either schizophrenic or mood disorders in the past, based on the criteria of the ICD-10. In the present study, recovered patients meant a score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved) on the Clinical Global Impression—Improvement scale. The study sample comprised 100 recovered women with mental illness and covered an age span of 18–60 years. We excluded symptomatic and cognitively impaired patients. Hence, recovered women with mental illness, those who are symptom free, may be the true representative of the target population because in the absence of mental illness, they can ascertain and defend their rights.

Measurement tools

Clinical global impression-improvement scale

This was a standardized assessment tool used to rate the severity of illness, change over time, and efficacy of medication, taking into account the patient's clinical condition and the severity of side effects. The CGI-I is rated on a seven-point scale, with the severity of illness scale using a range of responses from 1 (normal) to 7 (among the most severely ill patients).[14]

Socio-demographic schedule

The socio-demographic details taken were age, gender, educational status, marital status, employment, residence, religion, monthly income, type of family, diagnosis and duration of illness (in months).

Needs assessment questionnaire

This questionnaire comprises two sections. Section A was developed by the researchers, based on the UDHR[15] and a review of the literature, to assess the human right needs in the family domain. This tool has 58 items under five dimensions: Physical, emotional, religious, social, and ethical needs. This is a four-point (ordinal) scale, rated 0 (never) to 3 (always). There is no right or wrong answers.

The items in the physical needs dimension (18 items) focus mainly on article 25 in the UDHR to assess the right to a decent life, including adequate food, clothing, housing and medical care services (e.g, availability of light, electricity, safe drinking water, food common for family members, etc.).

The items in the emotional needs dimension (18 items) were based on article 5 (no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment) and article 12 (no one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation) of the UDHR to evaluate emotional needs (e.g. family environment helps to maintain dignity, commenting on physical appearance, privacy in terms of opening mails, monitoring phone calls, etc).

The items in the religious needs dimension (four items) assess the religious rights of the participants based on article 18 (everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion) of the UDHR (e.g. forcing to practice other religious and witchcraft/black magic activities, etc).

The items in the social needs dimension (eight items) were based on article 13 (everyone has the right to freedom of movement) and article 20 (everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association) of the UDHR to measure social and economic rights (e.g. allowing the participants to go out of the home, keeping them from going to a job/school by their family members, allowing them to handle money, etc).

The items of the ethical needs dimension (10 items) were based on articles 1, 2, 3, 16, 17 and 26 of the UDHR to assess the right to equality in dignity, right to live in freedom and safety, right to marry, right to own property and right to education.

In section B, the researchers used a modified version of Taking the Human Rights Temperature of your Community developed by World Health Organization[16] to assess human rights needs of people with mental illness in the community domain. This scale contains 25 items with a five-point scale, rated 0 (don’t know) to 4 (always). The above-mentioned instruments were formulated in the English language and administered in the format of face-to-face interview.

This tool was modified to suit to the Indian context (related to mental illness), without losing the essence of questions. For example, “My community is a place where residents are safe and secure” was modified to “My community is a place where mentally ill patients are safe and secure.” Items 12, 17, 18, 21 and 22 were completely changed as suggested by the experts. According to the Indian constitution and international covenants (international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights and international covenant on civil and political rights), right to vote, right to continuing education and right not to be discriminated against are given more importance, and exploring these issues were more relevant to the present study.

Validity and reliability of the tools

The needs assessment questionnaire was validated by eleven experts from various fields such as nursing, psychiatry, psychiatric social work, psychology, human rights and statistics. The final questionnaire was modified according to the experts’ suggestions. The scale's reliability assessment was done by using the test–retest method. The researchers administered the tool on 10 recovered psychiatric patients at the follow-up outpatient department over a two-week period and found that the study was feasible. Any modifications deemed necessary were made. The reliability coefficient for the structured questionnaire was 0.96.

Data were collected by the primary author through face-to-face interview, in a private room at the treatment facilities where the participants were recruited. It took approximately 45 minutes to complete the structured questionnaire. The researchers educated the family members in groups regarding the rights of persons with mental illness.

Ethical consideration

Permission was obtained by the concerned hospital authorities. The study protocol was approved by review committee. Written consent was obtained from the participants and they were given freedom to quit the study. Participants’ confidentiality was respected.

Statistical analysis

Responses of the negatively worded items were reversed before data analysis. The data were analyzed using appropriate statistics and the results were presented in narratives and tables. Descriptive (frequency and percentage) statistics were used to interpret the data.

Results

The sample comprised of women (N = 100) recovered from mental illness, of whom 58% were illiterates. The mean age for the illiterate woman was 36.13 ± 9.79 years (M ± SD) and that of literate participants was 33.33 ± 1.02 years (M ± SD). Similarly, majority were married, homemakers and Hindus (86.2% and 88.1%). More number of illiterate women (56.9%) belonged to below poverty line group (monthly income Rs/- 1700) compared to 31% of literate women ((χ2 = 6.601, P < 0.010). However, majority of them from both groups were diagnosed having mood disorders (53.4% and 61.9%) [Table 1].

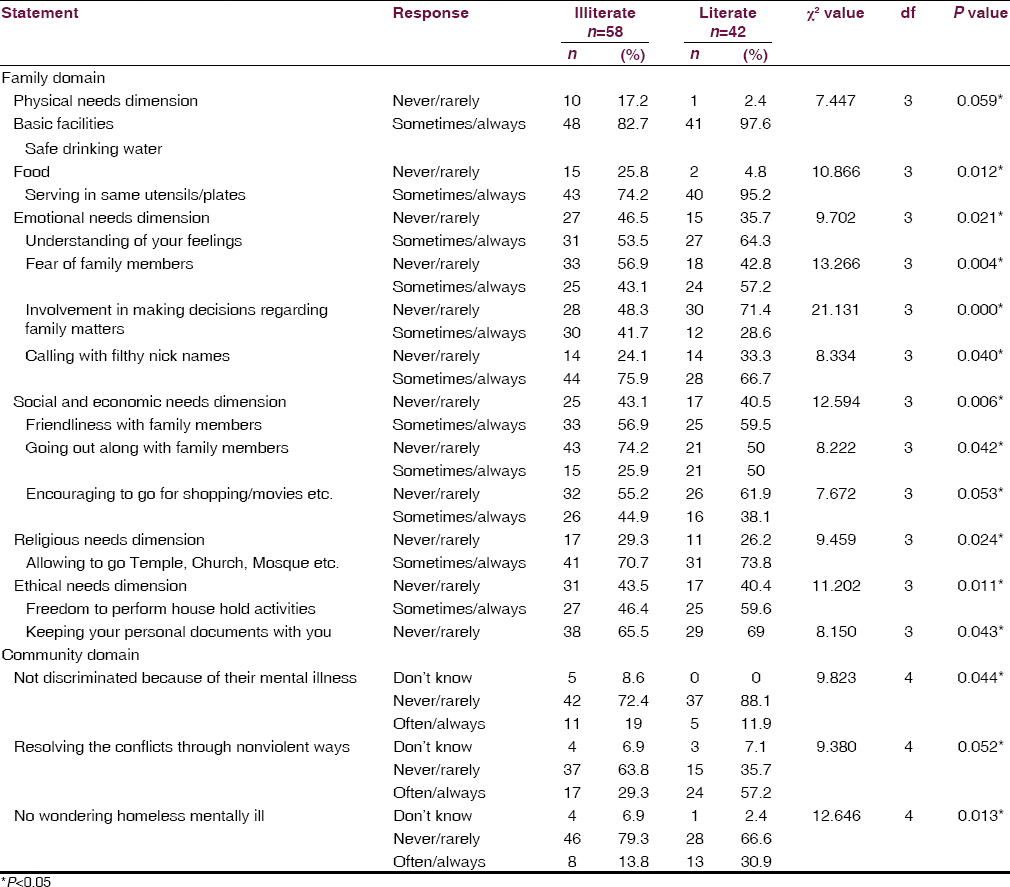

Table 2 represents participants responses related to their satisfaction in meeting human right needs in physical, emotional, religious, social, economic, and ethical needs dimensions at family level. Concerning physical needs, almost all the literate women (97.6%) than illiterates (82.7%) were accessible to “safe drinking water” (χ2 = 7.447, P < 0.05). Similarly, 95.2% of literates compared to 74.2% of the illiterate women were “served food in the same utensils/plates” (χ2 = 10.866, P < 0.01). With regard to emotional needs, nearly half of the illiterate women felt that their “feelings were not acceptable by the family members” (χ2 = 9.702, P < 0.021). Interestingly, majority of literates (57.2%) than illiterate women (43.1%) were “afraid of family members” (χ2 = 13.266, P < 0.004). More number (71.4%) of literate women than illiterates (48.3%) felt that they were “never/rarely” involved in “making decisions regarding family matters” (χ2 = 21.133, P < 0.00). Three fourths of illiterate women expressed that they were “called with filthy nick names” (χ2 = 8.334, P < 0.040). More number of illiterate women (43.1%) than literates agreed that their “family members were not friendly with them” (χ2 = 12.594, P < 0.006). Likewise, 74.2% of illiterate women than 50% of literates stated that they had “not gone out along with their family members” (χ2 = 8.222, P < 0.042). In contrast, majority of literate women (61.9%) opined that they were never “encouraged to go for shopping/movies etc” than illiterate women (χ2 = 7.672, P < 0.053). With related to religious needs, more number of literates (73.8%) than illiterate women were “allowed to go to Temple, Church, Mosque etc” (χ2 = 9.459, P < 0.024). In the ethical need dimension, nearly half of the illiterate women approved that they didn’t have “freedom to perform house hold activities” than literate women (χ2 = 11.202, P < 0.011). Although, statistical association was found, majority of literate (69%) and illiterate women (65.5%) felt that they were never “allowed to keep their personal documents with them” (χ2 = 8.150, P < 0.043). More number of literates (88.1%) than illiterate women (72.4%) accepted that they were “discriminated by the community members because of mental illness” (χ2 = 9.823, P < 0.044). In contrast, more number of illiterate women agreed that “wondering homeless people with mental illness were there in the community” (χ2 = 12.646, P < 0.013).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first innovative study carried out among recovered women with mental illness from India to examine the role of education in meeting human rights needs at family and community levels. Previous studies investigated symptomatic psychiatric patients to assess their views in meeting the basic needs.[17181920] Hence, the responses from the acutely ill psychiatric patients were questionable. Further,[21] the asymptomatic patients’ expectations from others were explored, but it was only in a psychological dimension. The present study was unique in nature as the participants were recovered from mental illness and they were well aware of diagnosis and were able to comprehend the questions asked by the researchers related to the study. Further, we assessed comprehensively about the human right needs in physical, emotional, socioeconomic and ethical needs at family level.

In the present study, the number of literate women (48%) is slightly lower than women with illiteracy (52%). This indicates female literacy rate is 54.28%, which is less compared to male literacy rate (75.96%) in India. Unlike the previous research that described that limited literacy was an added barrier to accessing and using mental health services effectively,[222324] the present study showed effective mental health service utilization among women without education.

According to International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 2002), the human right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity. It is a prerequisite for the realization of other human rights (Article I.1). Further, the right to water was defined as the right of everyone to have sufficient, safe, acceptable and physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.[25] Yet, billions of people throughout the world still do not enjoy these fundamental rights.[26] Studies indicate that people without education usually give more attention to quantity of water than quality of water.[27] The present study also supports this argument, as a more number of literate women were accessible to safe drinking water. Similarly, 95.2% of literates compared to 74.2% of the illiterate women were “served food in the same utensils/plates” (χ2 = 10.866, P < 0.01). These findings could be due to the misconceptions among the family members that mental illness is contagious. Hence, it is crucial for all the mental health professionals to educate the family members about cause and nature of mental illness.

In the current study, literate women were afraid of family members (57.2%) and were not involved in making decisions regarding family matters (71.4%). Further three fourths of illiterate women expressed that they were “called with filthy nick names” (χ2 = 8.334, P < 0.040). These findings were similar to a recent survey[28] conducted in Andhra Pradesh to observe human rights of people with disabilities (includes mental illness). The above-mentioned findings indicate that the right to live with dignity violated by the family members could be because of their negative attitudes toward the people with mental illness. Stigma is painful and humiliating and worsens the lives of people with mental illness. In other words, stigma can be highlighted by commenting typical disgusting words like “loony,” “psycho,” or “crazy,” though they may seem harmless but can be spiteful[2129] provided evidence that people with mental illness wanted to be treated in the same way as the other people are, namely with respect, good manners, and kindly. They also longed for empathy and a positive attitude toward them. The present study also support the previous research which highlighted the deficits in emotional support for people with chronic mental illness.[3031]

Evidence from the World Health Organization suggests that nearly half of the world's population were affected by mental illness with an impact on their self-esteem, relationships and ability to function in everyday life.[32] Similarly, in the current study, more number of illiterate women than literates agreed that their “family members were not friendly with them” (χ2 = 12.594, P < 0.006) and “not gone out along with their family members” (χ2 = 8.222, P < 0.042). Further, 73.8% of literates than illiterate women were “allowed to go to Temple, Church, Mosque etc” (χ2 = 9.459, P < 0.024). Usually, it was a general belief that people with mental illness are violent toward others. In fact, people with mental illness are victims of violence, stigma and discrimination. It is frustrating to notice active deprivation of economic and social rights by the family members as illiterate women with mental illness didn’t have “freedom to perform house hold activities” (χ2 = 11.202, P < 0.011) and never “allowed to keep their personal documents with them” (χ2 = 8.150, P < 0.043). The importance of social support for people with mental illness has been emphasized in recent years. This has resulted from studies showing that family and professional support plays an important role in preventing re-hospitalization and to improve quality of life of patients with major psychiatric disorders.[33] Mental health professionals should take active initiation in educating the families regarding the importance of providing an environment that respects and protects basic civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights of the people with mental illness.

The stigma against mental illness is an issue of human rights. The stigma associated with mental illness is the greatest obstacle in facing the mental health community in India. A stigma is the cultural attitude or system of negative beliefs that motivate the public to fear, reject, and discriminate against people with mental illnesses. It hinders people with mental illness from obtaining the simplest human rights, prevents them from living with dignity, and forces them live in darkness, unaware about their own illness.[34] Likewise, in the present study, 88.1% of literate than illiterate women (72.4%) accepted that they were “discriminated by the community members because of mental illness” (χ2 = 9.823, P < 0.044). These findings support previous studies.[35363738] Most importantly, more number of illiterate women agreed that “wondering homeless people with mental illness were there in the community” (χ2 = 12.646, P < 0.013). According to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), there are over 70 million people with some form of mental illness in the country and about a quarter of them are homeless. Homelessness is a crucial issue for women especially for those suffering from mental illness. A study conducted in Delhi found that approximately 2500 women with mental illness were virtually on the street. If it extrapolates for the whole nation, the country will have nearly 150,000 mentally ill destitute women.[2] A homeless woman with mental illness is extremely vulnerable for sexual abuse and needs urgent support and care from both Government and non-government organizations. The misconceptions about mental illness and discrimination of women with mental illness can affect all aspects of their lives, denying their civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights and impact negatively on their access to care and integration into society.

Limitations

The study was restricted to women psychiatric patients at outpatient department and smaller sample size made difficult to generalize the findings. Therefore, further research should focus on larger sample size and qualitative approach including family members, and exploratory studies may be helpful for in-depth understanding of human rights issues among these disadvantaged populations.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study clearly illustrated human rights violations exist irrespective of educational status among women with mental illness in meeting the basic needs at family and community levels. Women with education were satisfied to a certain extent in meeting their physical needs than illiterate women with mental illness. Literate women were more dissatisfied than those without education in the emotional needs domain. On the contrary, women without education were deprived of physical, emotional, religious, and ethical needs dimensions. Therefore, it is crucial to improve literacy of women and there is an urgent need to strengthen the legal framework to protect the rights of the women with mental illness.

Acknowledgements

Researchers thank all the participants for their valuable contribution.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Integrating women's human rights into global health research: An action framework. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:2091-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Seminar. Mentally ill Women. Is Destitution the only Answer? 2007. Avaialable from: http://www.ncw.nic.in/./Mental_health_is_destitution_the_only_answer.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Women's Issues in India. Available from: http://www.indianchild.com/womens_issues_in_india.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- CEDAW. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/

- [Google Scholar]

- DEVAW. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights. 1993. http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/48/a48r104.htm/

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Promoting and Protecting the Rights of People with Mental Disorders: Information Sheet No. 1. 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; http://www.who.int/mental_health/./1_PromotingHRofPWMD_Infosheet.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health of Indian Women: A Feminist Agenda. New Delhi: Sage Publications; 1999. p. :281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Literacy in India: Despite Tall Claims, Literacy in India is Still Low! Merinews -Power to People 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental health in the new millennium: Research strategies for India. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trans-cultural issues in psychosocial rehabilitation. In: Kalyanasundaram S, Varghese M, Krahl W, eds. Innovations in Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Bangalore India: The Richmond Fellowship Society; 2000. p. :30-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO and mental health--a view from developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:502-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Culture, control, and family involvement: A comparison of psychosocial rehabilitation in India and the United States. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25:273-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976.

- [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Paris: General Assembly of the United Nations; Available from: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/

- [Google Scholar]

- The Human Rights Education Handbook: Effective Practices for Learning, Action and Change. 2000. Minneapolis, MN:: Human Rights Resource Center, The Stanley Foundation; Available from: http://www.crin.org/docs/resources/publications/hrbap/Human_rights_education_handbook.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Needs assessed by patients and staff in a Swedish sample of severely mentally ill subjects. Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55:311-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patients’ and staff members’ attitudes about the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Servs. 2002;53:87-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of relatives in discharge planning from psychiatric hospitals: The perspective of patients and their relatives. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76:297-315.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health outcomes for people with serious mental illness: A case study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2003;39:23-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- The mentally ill: The way they perceive their own illness and their expectations from the society. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57(Suppl 4):191-8. 2006

- [Google Scholar]

- Patients who can’t read: Implications for the health care system. JAMA. 1995;274:1719-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shame and health literacy: The unspoken connection. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:33-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of low literacy in an indigent psychiatric population. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:262-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). General Comment No. 15, UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: The Right to Water. 2002. World Health Organization; http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/gencomm/econ.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Special Rapporteur on the Human Right to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation. 2014. http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/human_right_to_water.shtml

- [Google Scholar]

- Swadhikaar Center for Disabilities Information. Monitoring the Human Rights of People with Disabilities in India. Country Report: Andhra Pradesh, India. 2009. Canada: Disability Rights Promotion International (DRPI); http://www.yorku.ca/drpi/files/IndiaCountryReport.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Society Affix Stigma with Mental Illness. Available from: http://www.thisismyindia.com

- [Google Scholar]

- Social support of chronically mentally ill patients. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2008;2:13-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceived social support and community adaptation in schizophrenia. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:955-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review: Students with mental health problems--a growing problem. Int J Nurs Pract. 2010;16:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of social support on the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Pol. 2004;38:443-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- The stigma of schizophrenia from patients’ and relatives’ view: A pilot study in an Italian rehabilitation residential care unit. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2007;3:23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public attitudes towards people with mental illness in England and Scotland, 1994-2003. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:278-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Community attitudes towards discriminatory practice against people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:159-74.

- [Google Scholar]