Translate this page into:

Atypical Presentation of Severe Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: An Important Diagnosis in Neurocritical Care

Hansen Deng, MD Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center 200 Lothrop St., Suite B-400, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 United States hdneurosurg@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

First described by Hinchey et al in 1996,1 posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) remains a diagnostic challenge, particularly among the underserved patient population due to inadequate medical access and because risk factors in these individuals are far greater. Symptomology includes headache, seizures, encephalopathy, and visual disturbances.2 Precipitating etiologies include preeclampsia or eclampsia, acute hypertension, renal failure, autoimmune disorder, sepsis, and the use of cytotoxic drugs. MRI patterns of PRES classically show edema in the parietal-occipital lobe,3 but that is not always the case. Herein, the authors present a patient who experienced acute neurological deterioration and a constellation of findings, which were ultimately concerning for severe, atypical PRES.

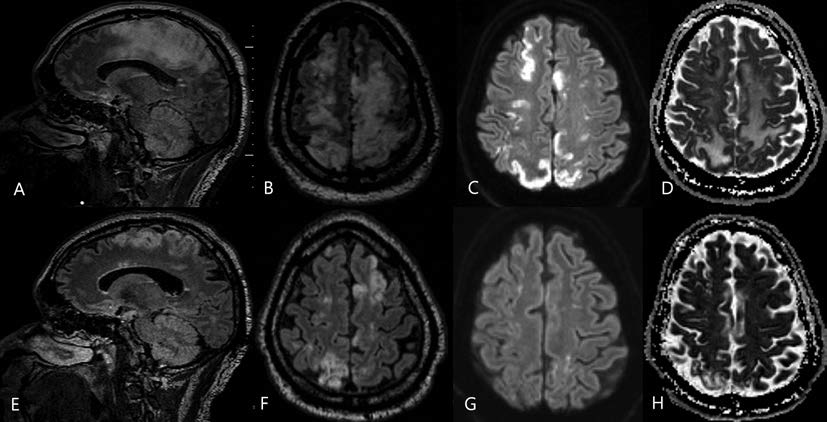

The patient is a 51-year-old man with Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus (MSSA) bacteremia and necrotizing fasciitis from a transmetatarsal amputation (TMA) stump wound. Emergent guillotine below-knee amputation was performed, as well as surgical washout for septic arthritis. The initial postoperative course was unremarkable, but on day 7, the patient became unresponsive from encephalopathy comprising confusion, aphasia, and complete loss of motor strength in the left upper and right lower extremities. MRI showed profound bihemispheric subcortical vasogenic edema and multifocal cortical diffusion restriction (Fig. 1A D). The initial diagnosis was embolic strokes of watershed regions of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA)-middle cerebral artery (MCA) and ACA-posterior cerebral artery (PCA). However, with a complete negative infectious workup and no clear etiology for the encephalopathy, the clinical and radiographic features of the patient pointed toward an atypical and severe manifestation of PRES. Interval MRI at 1 month showed resolution and expected evolution of multifocal infarcts (Fig. 1E H). While his cognition and speech improved, the patient remained bedbound due to impaired mobility.

-

Fig. 1 Reversal of diffusion abnormalities in a 51-year old man with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) due to infection. The MRI sections (A-D) illustrate findings shortly after the onset of encephalopathy, and the bottom panel (e-h) demonstrates findings from reimaging 1 month later. (A) Sagittal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) shows increased T2-weighted intensity in the gray matter and subcortical white matter. (B) Axial FLAIR shows increased bihemispheric signal intensity. (C) Axial diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates increased restricted diffusion in the same distribution as the T2-weighted abnormality. (D) Axial apparent diffusion coefficient. (E) Sagittal FLAIR and (F) axial FLAIR show decreased T2-weighted signal abnormality. (G) Axial diffusion-weighted and (H) apparent diffusion coefficient sections show that previously noted restricted diffusion to have resolved.

Fig. 1 Reversal of diffusion abnormalities in a 51-year old man with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) due to infection. The MRI sections (A-D) illustrate findings shortly after the onset of encephalopathy, and the bottom panel (e-h) demonstrates findings from reimaging 1 month later. (A) Sagittal fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) shows increased T2-weighted intensity in the gray matter and subcortical white matter. (B) Axial FLAIR shows increased bihemispheric signal intensity. (C) Axial diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates increased restricted diffusion in the same distribution as the T2-weighted abnormality. (D) Axial apparent diffusion coefficient. (E) Sagittal FLAIR and (F) axial FLAIR show decreased T2-weighted signal abnormality. (G) Axial diffusion-weighted and (H) apparent diffusion coefficient sections show that previously noted restricted diffusion to have resolved.

MRI is more sensitive and the preferred diagnostic tool to evaluate PRES and should not be overlooked in the rural critical care setting.4 Bartynski et al described three major imaging patterns: holohemispheric watershed, superior frontal sulcal, and parietal-occipital.4 There is notable heterogeneity, and the findings in this patient are nonposterior and irreversible.5 6 T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences can reveal bilateral, asymmetric brain edema of the subcortical white matter and less commonly the cortex. The presence of extensive cortical restricted diffusion is uncommon in patients with PRES; 7 however, it can be associated with irreversible injury and incomplete recovery.

In conclusion, this patient had several medical comorbidities that contributed to the onset of severe neurotoxicity. The clinician should obtain complete diagnostic workup to localize the etiology of the neurologic deficit. The prognosis of PRES is usually favorable with complete recovery within a week of resolution of the precipitating cause. However, clinical improvement may also take weeks to months with persistent neurological deficits.

Authors’ Contributions

H.D. and J.K.Y. interpreted the data, drafted, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. P.M. interpreted the data, reviewed, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content.

Ethical Approval

Informed consent was obtained, and patient information was deidentified in the data reporting. Institutional review board approval was not required as the study did not contain investigation utilizing human or animal participants.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(8):494-500.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome: evaluation with diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology. 2001;219(3):756-765.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: associated clinical and radiologic findings. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(5):427-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distinct imaging patterns and lesion distribution in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(7):1320-1327.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, part 1: fundamental imaging and clinical features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(6):1036-1042.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: incidence of atypical regions of involvement and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(4):904-912.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(9):914-925.

- [Google Scholar]