Translate this page into:

Assessment of the Knowledge of Risk Factors of Congenital Hydrocephalus among Mothers Attending Antenatal Clinics in a Rural Tertiary Hospital Irrua, Edo State

Chibuikem A. Ikwuegbuenyi, MBBS Luth Hostel College of Medicine University of Lagos Nigeria Ishaga Rd, Idi-Araba, Lagos, Nigeria ikwuegbuenyichibuikem@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Background One of the congenital central nervous system malformations with great impact on the mental and psychosocial development of children is congenital hydrocephalus and it happens to be one of the most common. A large vacuum exists between knowledge on maternal environmental risk factors associated with congenital hydrocephalus, most especially in our rural community which consists of a large segment of our society. Our study aimed to determine the knowledge and perception of mothers on factors existing in the maternal environment that potentially puts an increased risk of developing congenital hydrocephalus.

Materials and Methods This was a cross-sectional study design spanning a period of 8 months (March 2018–October 2018), in which the knowledge and perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among mothers attending antenatal clinic in Irrua specialist teaching hospital, a rural tertiary hospital in Irrua, Edo state, Nigeria, were assessed using a random sampling technique. Interviewer-administered questionnaires (reviewed and validated) were used. The data collected were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 21.

Results The findings showed varying levels of knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus. Less than half (44.0%) of the respondents had poor knowledge, 34.5% had fair knowledge, and 21.6% had good knowledge. There was a statistically significant relationship between knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and respondents’ knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus. Most (52.6%) had good perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus, while 23.3% had poor perception.

Conclusion This study revealed a fairly good knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and its risk factors among mothers, most especially those with a good level of education.

Keywords

assessment

knowledge

perception

risk factor

congenital hydrocephalus

antenatal

Introduction

Hydrocephalus is a clinical disease that develops as a result of increase in the size of the cerebral ventricles, this increase which is usually progressive, is due to the disruptive movement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the choroid plexus (the site of CSF production) to its sites of absorption into the systemic circulation.1

There exists a vacuum of knowledge on risk factors in the maternal environment that is associated with congenital hydrocephalus, albeit that several studies have previously evaluated the child-related risk factors associated with congenital hydrocephalus development.1

Maternal febrile illness in the first trimester, maternal age > 35 years, use of herbal medications, exposure to drugs, and lack of use of periconceptional folic acid supplementation were the possible risk factors for various central nervous system anomalies especially neural tube defects, a closely related condition to hydrocephalus and these factors may impact the incidence of at least the congenital variety of hydrocephalus in any geographic area.2

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

Approval for the research was granted by the ethical committee of Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua. Before administering the questionnaire, informed consent was obtained from each participant after indicating the purpose of the research and reassuring confidentiality of any information to be obtained.

Study Area

Edo State lies between longitudes 5°and 6°45' East, and latitudes 6°1' and 7°30' North with a total land area of 19,281.93 km2.3 According to the 2006 Population and Housing Census, Edo State has a total count of 1,633,946 males and 1,599,420 females (a total of 3,233,366), the 2016 projection with a population growth rate of 2.7% per annum is approximately 4 million population.4 Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua is a rural Federal Teaching Hospital and the only functional tertiary healthcare facility in the entire Edo central senatorial district.3

Study Design

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study involving 116 subjects who met the inclusion criteria and this study spanning a period of 8 months (March 2018–October 2018), at Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, a rural tertiary hospital in Irrua, Edo state, Nigeria were assessed using a random sampling technique.

Study Participants

Mothers attending the antenatal clinic in the hospital were admitted in the study by successively approaching each potential participant and those who gave their consent to participate in the study were given a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire, to obtain data from them, focusing on the knowledge and perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus.

Study Tool

Structured interviewer-administered questionnaires were used in this study.

The questionnaire was adapted from a review of available literature.

The questionnaire consists of four parts which are; the socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus among pregnant women, risk factors present in pregnant women that may predispose them to having children with congenital hydrocephalus, and perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among pregnant women.

Data Analysis

The data gathered was inputted into and analyzed using SPSS version 21. Variables were measured as continuous and were expressed as mean and standard deviation while qualitative variables were expressed in frequencies and proportions. In scoring/grading of the knowledge, a total of seven questions were asked and a score of two was allotted to each question answered correctly while a score of 0 (zero) was given to each question answered wrongly; a total score of 14. Those who scored below five (score of < 40%) were assessed as having poor knowledge, while those that scored above nine (> 70%) were assessed as having good knowledge. All tests of significance using Fischer’s exact method were done with a level of significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Respondents were mostly in the age range of 30 to 39 years (46.6%). All (100%) of the participants were females in their first pregnancy or mothers who had up to three children (31.9%). Most (55.2%) of the respondents were Esan, followed by Etsako (25.9%), and Bini (10.3%). Most were Christians (68.1%) and most of them were married (85.3%). Most (64.7%) had attained a tertiary level of education and 41.4 and 31.0% of them were civil servants and traders respectively (Table 1).

|

Variable |

Frequency (n = 116) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

aOthers: Urhobo 3 (2.6%); Yoruba 2 (1.7%); Owan 4 (3.4%). |

||

|

Age group (years) |

||

|

20–29 |

47 |

40.5 |

|

30–39 |

54 |

46.6 |

|

40–49 |

15 |

12.9 |

|

Mean ± standard deviation |

31.92 ± 5.38 |

|

|

Sex |

||

|

Female |

116 |

100 |

|

Ethnicity |

||

|

Bini |

12 |

10.3 |

|

Esan |

54 |

55.2 |

|

Etsako |

30 |

25.9 |

|

aOthers |

10 |

8.6 |

|

Religion |

||

|

Christianity |

79 |

68.1 |

|

Islam |

36 |

31.0 |

|

African traditional |

1 |

9 |

|

Marital status |

||

|

Divorced |

5 |

4.3 |

|

Married |

99 |

85.3 |

|

Single |

11 |

9.5 |

|

Widow/widower |

1 |

9 |

|

Level of Education |

||

|

No formal education |

7 |

6.0 |

|

Primary |

7 |

6.0 |

|

Secondary |

27 |

23.3 |

|

Tertiary |

75 |

64.7 |

|

Occupation |

||

|

Civil servant |

48 |

41.4 |

|

Doctor |

1 |

9 |

|

Farmer |

6 |

5.2 |

|

Self employed |

17 |

14.7 |

|

Student |

8 |

6.9 |

|

Trader |

36 |

31.0 |

|

Number of Children |

||

|

Nulliparous |

15 |

12.9 |

|

1-4 |

96 |

82.8 |

|

>5 |

5 |

4.3 |

|

Antenatal visit in last pregnancy |

||

|

Yes |

93 |

80.2 |

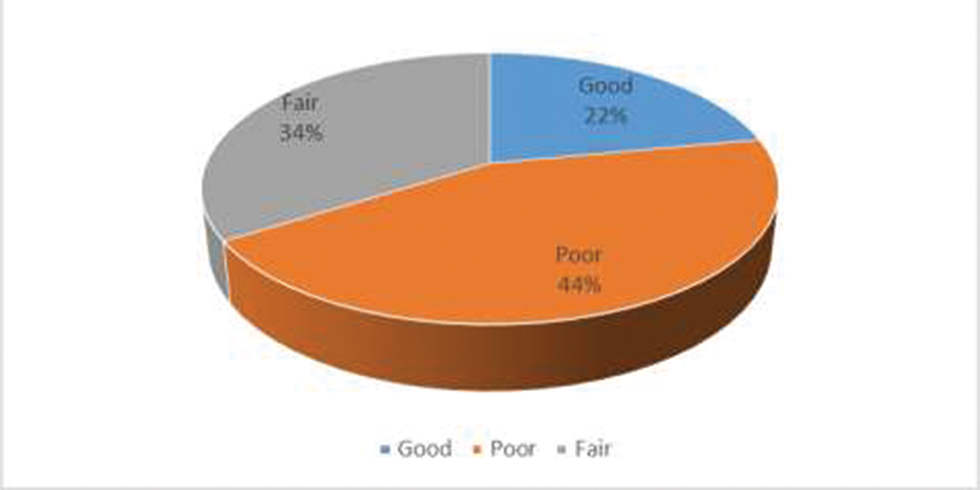

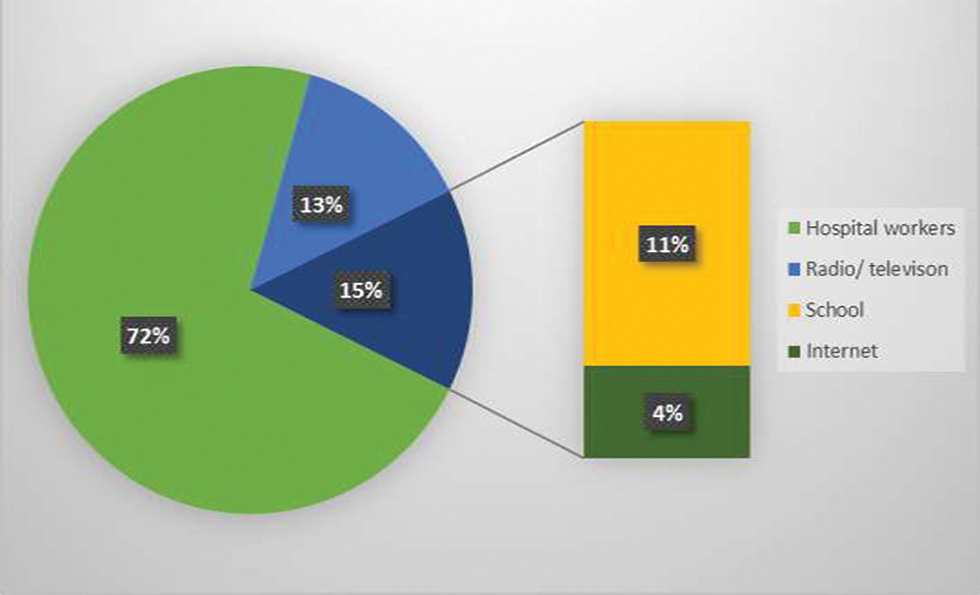

Of the 116 respondents, 64.7% had heard about congenital hydrocephalus. 12.1% defined hydrocephalus correctly and only 10.3% had correct knowledge of the clinical presentation of congenital hydrocephalus. Most (62.9%) knew it could be detected during pregnancy, while most (59.5%) knew about the ways it could be detected during pregnancy. 51.7% had seen a child with congenital hydrocephalus. Out of the 116 respondents, majority (70.7%) did not think congenital hydrocephalus was associated with any other disease, while of the 33 respondents who thought it was, 22.4% answered correctly (Table 2). Most (44%) had poor knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus, while 22% had good knowledge (Fig. 1). Majority of the respondents (70%) had hospital workers as their source of information on congenital hydrocephalus, while the least common source of information (4%) was the internet (Fig. 2).

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Heard about congenital hydrocephalus |

n = 116 75 |

64.7 |

|

Knows what congenital hydrocephalus is |

n = 115 14 |

12.1 |

|

Knows its presentation |

n = 115 12 |

10.3 |

|

Knows congenital hydrocephalus can be detected in pregnancy |

n = 116 73 |

62.9 |

|

Knows ways of detection during pregnancy |

n =75 69 |

59.5 |

|

Has seen a child with congenital hydrocephalus |

n =116 60 |

51.7 |

|

Can itemize problems or complications observed in the child |

n =59 28 |

24.1 |

|

Thinks congenital hydrocephalus is associated with other diseases |

n =116 34 |

29.3 |

|

Knows the diseases associated with congenital hydrocephalus |

n =33 26 |

22.4 |

-

Fig. 1 Knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

Fig. 1 Knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

-

Fig. 2 Respondents source of information on congenital hydrocephalus.

Fig. 2 Respondents source of information on congenital hydrocephalus.

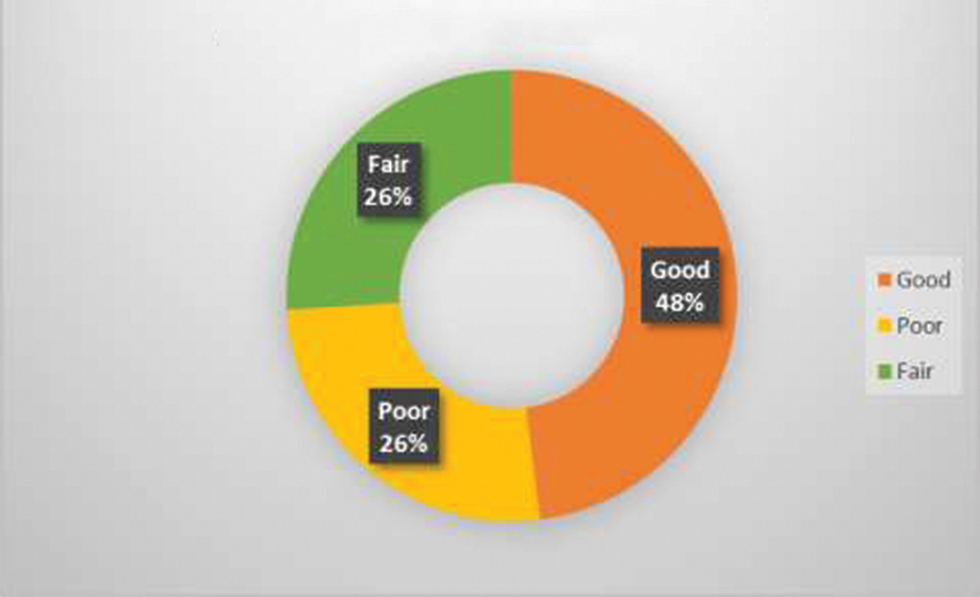

Of the 116 respondents, 59.5% knew that the age of a woman at first pregnancy predisposes her to having a child with congenital hydrocephalus, 51.7% knew that low socioeconomic status was a risk factor. Most (78.4%) knew that lack of prenatal and antenatal care was a risk factor. Only 39.7% knew that cultural factors were risk factors, while 62.9% knew that having a family history was a risk factor. Majority (70.7%) knew about smoking during the period of pregnancy, 50.9% knew about hypertension, 68.1% knew about maternal infections, 56.0% knew about maternal diabetes, 57.8% knew about maternal obesity, 52.6% knew about trauma to the mother, 74.1% knew about maternal drug abuse during the period of the pregnancy, while 73.3% knew about maternal alcohol use during the period of pregnancy as risk factors to congenital hydrocephalus (Table 3). Most (48%) had good knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus, while 26% had poor knowledge (Fig. 3).

|

Risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus |

Frequency (n = 116) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age at primigravida |

69 |

59.5 |

|

Low socioeconomic status |

60 |

51.7 |

|

Lack of prenatal and antenatal care |

91 |

78.4 |

|

Cultural factors |

46 |

39.7 |

|

Family history |

73 |

62.9 |

|

Hypertension |

59 |

50.9 |

|

Smoking during the period of pregnancy |

82 |

70.7 |

|

Maternal infections |

79 |

68.1 |

|

Maternal diabetes |

65 |

56.0 |

|

Maternal obesity |

67 |

57.8 |

|

Trauma to the mother |

61 |

52.6 |

|

Maternal drug abuse during the period of pregnancy |

86 |

74.1 |

|

Maternal alcohol use during the period of pregnancy |

85 |

73.3 |

-

Fig. 3 Knowledge of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

Fig. 3 Knowledge of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

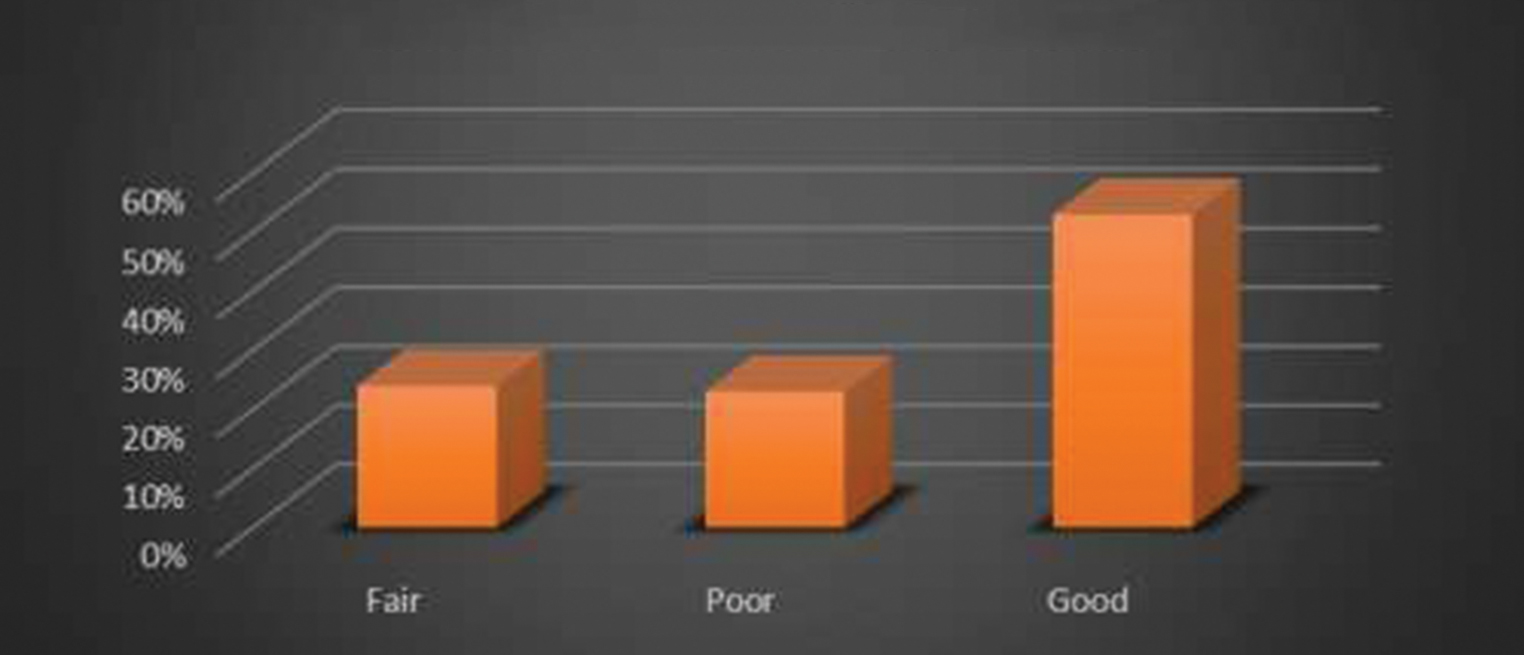

Of the 116 respondents, 75.0% were of the perception that congenital hydrocephalus affected only infants, 58.6% personally thought the age of a woman at first pregnancy predisposed her to having a child with congenital hydrocephalus, only 44.0% thought that low socioeconomic status was a risk factor. Most (78.4%) thought that lack of prenatal and antenatal care was a risk factor. More than half (50.9%) thought that cultural beliefs and having a family history was a risk factor, while only 44.3% thought that hypertension was a risk factor. Majority (79.3%) thought about smoking during the period of pregnancy, maternal infections (76.7%), maternal diabetes (62.9%), maternal obesity (65.5%), trauma to the mother (55.2%), maternal drug abuse, and alcohol use during the period of the pregnancy (82.8%). Only 60.3% thought that eating too much carbohydrates during the pregnancy period was not a risk factor to congenital hydrocephalus (Table 4). Most (52.6%) had good perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus, while 23.3% had poor perception (Fig. 4).

|

Respondents who thought that the following can result in congenital hydrocephalus |

Frequency (n = 116) |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Who do you think congenital hydrocephalus can affect? |

||

|

Infants |

87 |

75.0 |

|

Adults |

4 |

3.4 |

|

Both |

25 |

21.6 |

|

Age at primigravida |

68 |

58.6 |

|

Low socioeconomic status |

51 |

44.0 |

|

Lack of prenatal and antenatal care |

91 |

78.4 |

|

Cultural beliefs and family history |

59 |

50.9 |

|

Hypertension |

63 |

44.3 |

|

Smoking during the period of pregnancy |

92 |

79.3 |

|

Maternal infections |

89 |

76.7 |

|

Maternal diabetes |

73 |

62.9 |

|

Maternal obesity |

76 |

65.5 |

|

Trauma to the mother |

64 |

55.2 |

|

Maternal drug abuse and alcohol use during the period of pregnancy |

96 |

82.8 |

|

Eating too much carbohydrate during the pregnancy period |

46 |

39.7 |

-

Fig. 4 Perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

Fig. 4 Perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among respondents.

There is a statistically significant relationship between respondents’ knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and their knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus (Table 5).

|

Variable |

Score of knowledge of respondents |

X2 |

p -Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Does the age of a woman at first pregnancy predispose her to having a child with congenital hydrocephalus? |

Good n (%) |

Fair n (%) |

Poor n (%) |

||

|

aStatistically significant. |

|||||

|

Yes |

22 (88.0) |

30 (75.0) |

17 (33.3) |

26.902 |

0.000a |

|

Low socioeconomic status |

|||||

|

Yes |

19 (76.0) |

20 (50.0) |

21 (41.2) |

8.220 |

0.016a |

|

Lack of prenatal and antenatal care |

|||||

|

Yes |

25 (100.0) |

28 (95.0) |

28 (54.9) |

30.074 |

0.000a |

|

Cultural factors |

|||||

|

Yes |

16 (64.0) |

18 (45.0) |

12 (23.5) |

12.211 |

0.002 a |

|

Family history |

|||||

|

Yes |

20 (80.0) |

33 (82.5) |

20 (39.2) |

21.984 |

0.000 a |

|

Hypertension |

|||||

|

Yes |

21 (84.0) |

21 (52.5) |

17 (33.3) |

17.297 |

0.000 a |

|

Smoking during the period of pregnancy |

|||||

|

Yes |

25 (100.0) |

36 (90.0) |

21 (41.2) |

39.005 |

0.000 a |

|

Maternal infections |

|||||

|

Yes |

25 (100.0) |

36 (90.0) |

18 (35.3) |

45.810 |

0.000 a |

|

Maternal diabetes |

|||||

|

Yes |

23 (92.0) |

26 (65.0) |

16 (31.4) |

27.022 |

0.000 a |

|

Maternal obesity |

|||||

|

Yes |

21 (84.0) |

30 (75.0) |

16 (31.4) |

26.483 |

0.000 a |

|

Trauma to the mother |

|||||

|

Yes |

18 (72.0) |

29 (72.5) |

14 (27.5) |

23.064 |

0.000 a |

|

Maternal drug abuse during the period of pregnancy |

|||||

|

Yes |

24 (96.0) |

36 (90.0) |

26 (51.0) |

25.745 |

0.000 a |

|

Maternal alcohol use during the period of pregnancy |

|||||

|

Yes |

24 (96.0) |

35 (87.5) |

26 (51.0) |

23.671 |

0.000 a |

Discussion

The study aimed to determine the knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus, perception, and knowledge of the risk factors that were connected with congenital hydrocephalus among mothers attending antenatal clinic in a rural tertiary hospital. To achieve this, a total number of 116 women were interviewed for the study. All questionnaires were returned.

In this study, all of the respondents were female (100%) and married (85.3 %). Majority of the participants fell within the age group 30 to 39 years (46.6%) and the least number in the ≥40 years’ category (12.9%). Most had tertiary level of education (64.7%) as shown in Table 1.

Respondents showed varying levels of knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus. Most (44.0%) of respondents had poor knowledge, 34.5% had fair knowledge, and 21.6% had good knowledge as shown in Fig. 1. Most (51.7%) had fair knowledge of the clinical presentation of congenital hydrocephalus. Most (62.9%) knew it could be detected during pregnancy, while 59.5% knew about the ways it could be detected during pregnancy as seen in Table 2. However, of this, only few, could talk about congenital hydrocephalus without any help. From the fore going, it can therefore be concluded that of the respondents who knew about congenital hydrocephalus, most had not heard about the term congenital hydrocephalus; however, knew what it referred to, but awareness was poor generally. These findings were in keeping with previous studies, especially a study performed in Ibadan on 714 mothers, in which few of the respondents (25.6%) were observed to have good knowledge of birth defects including congenital hydrocephalus, and 13.3% reported that certain tests could be used to assist in prenatal diagnosis of these defects.5 The reason for this poor knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus was mostly due to illiteracy and lack of proper health education, there was a statistically significant link between level of education and knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus (p = 0.000).

Regarding the risk factors associated with congenital hydrocephalus such as the age of a woman at first pregnancy, low socioeconomic status, lack of prenatal and antenatal care, cultural factors, family history, hypertension, smoking during the period of pregnancy, maternal infections, maternal diabetes, maternal obesity, trauma to the mother, maternal drug abuse during the period of pregnancy, and maternal alcohol use during the period of pregnancy as shown in Table 4, 59.5% knew that the age of a woman at first pregnancy predisposed her to having a child with congenital hydrocephalus, 51.7% knew that low socioeconomic status was a risk factor. Most (78.4%) knew that lack of prenatal and antenatal care was a risk factor. Only 39.7% knew that cultural factors were a risk factor, while 62.9% knew that having a family history was a risk factor. Majority (70.7%) knew about smoking during the period of pregnancy, 50.9% knew about hypertension, 68.1% knew about maternal infections, 56.0% knew about maternal diabetes, 57.8% knew about maternal obesity, 52.6% knew about trauma to the mother, 74.1% knew about maternal drug abuse during the period of the pregnancy, while 73.3% knew about maternal alcohol use during the period of pregnancy as risk factors to congenital hydrocephalus. This was in keeping with other findings done on the risk factors that were connected with congenital hydrocephalus, especially a huge cohort study on timing of prenatal care initiation and risk of congenital malformations which showed that an absence of early prenatal care is remarkably associated with congenital hydrocephalus. This is also similar to a cross-sectional retrospective study performed in Enugu, Nigeria which revealed increased incidence of central nervous system anomalies in mothers >35 years of age.6 There was a statistically significant relationship between knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and respondents’ knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus. The reason for the relatively good knowledge about the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus was due to attendance of antenatal clinics by the women and health education by the doctors, nurses, and other health workers (80.2%), also most of the respondents who had good knowledge had tertiary level of education (64.7%).

Regarding the perception of risk factors associated with congenital hydrocephalus obtained in this study as shown in Table 4, majority (75.0%) were of the perception that congenital hydrocephalus affected only infants, 58.6% personally thought age of a woman at first pregnancy predisposed her to having a child with congenital hydrocephalus especially 35 and above and only 44.0% thought that low socioeconomic status was a risk factor. Most (78.4%) thought that lack of prenatal and antenatal care were risk factors, only 44.3% thought that hypertension was a risk factor. Majority (79.3%) thought about smoking during the period of pregnancy and few were of the perception that women should not smoke while pregnant. Majority were of the perception that maternal infections (76.7%), maternal diabetes (62.9%), maternal obesity (65.5%), trauma to the mother (55.2%), and maternal drug abuse and alcohol use during the period of the pregnancy (82.8%) were risk factors implicated in congenital hydrocephalus. Only 60.3% thought that eating too much carbohydrate during the pregnancy period was not a risk factor to congenital hydrocephalus. Fig. 3 showed that most (52.6%) had good perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus, while 23.3% had poor perception, and this was not in keeping with the findings of other researchers, especially a study by Esposito et al7 on 513 women selected from five hospitals in Naples, Italy and another study performed on 100 mothers in Abeokuta South Local Government Area of Ogun State.8 The reason for this relatively good perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus was due to the age and level of education of respondents, perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus was found to be best among respondents aged between 30 to 39 (34%) and a statistically significant association was found between age and perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus (p = 0.054) as shown in Table 6. Perception was found to be best among respondents with tertiary level of education (29.3%), and a statistically significant association was found between level of education and perception of risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus (p = 0.001).

|

Variable |

Score of perception of respondents |

X2 |

p-Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

aStatistically significant. |

|||||

|

Age group (years) |

Good (%) |

Fair (%) |

Poor (%) |

||

|

20–29 |

24 |

13 |

10 |

9.288 |

0.054a |

|

30–39 |

34 |

9 |

11 |

||

|

40–49 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

||

|

Sex |

|||||

|

Female |

61 |

28 |

27 |

||

|

Marital status |

|||||

|

Divorced |

1 |

2 |

2 |

7.298 |

0.296 |

|

Married |

56 |

21 |

22 |

||

|

Single |

4 |

4 |

3 |

||

|

Widow |

0 |

1 |

0 |

||

|

Level of education |

|||||

|

No formal education |

0 |

3 |

4 |

22.276 |

0.001a |

|

Primary |

2 |

0 |

5 |

||

|

Secondary |

12 |

9 |

6 |

||

|

Tertiary |

47 |

16 |

12 |

||

|

Occupation |

|||||

|

Civil servant |

30 |

11 |

7 |

14.695 |

0.144 |

|

Doctor |

1 |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Farmer |

1 |

2 |

3 |

||

|

Self-employed |

10 |

6 |

1 |

||

|

Student |

4 |

1 |

3 |

||

|

Trader |

15 |

8 |

13 |

||

|

Number of children |

|||||

|

0 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

10.714 |

0.554 |

|

1 |

9 |

3 |

7 |

||

|

2 |

11 |

8 |

5 |

||

|

3 |

23 |

5 |

9 |

||

|

4 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

||

|

5 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

||

|

6 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

||

|

Antenatal visit during the last pregnancy |

|||||

|

Yes |

9 |

7 |

7 |

2.091 |

0.352 |

|

No |

52 |

21 |

20 |

||

In this study, the respondents’ knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and their perception of the risk factors as shown in Table 5 were statistically significant (p = 0.000). Also, most (52.6%) had good perception of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus while 48.3% had good knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus. The commonest reason of their knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus was good level of education (tertiary level). Other reasons were health education by health care workers, antenatal visits, and a knowledgeable occupation (doctors and civil servants).

Conclusion

This study has provided an insight into the knowledge of the risk factors of congenital hydrocephalus among mothers attending antenatal clinic in a rural tertiary hospital in Irrua, Edo state. It revealed that their knowledge is fairly good, and most of the mothers knowledgeable about the risk factors that could predispose to hydrocephalus were those with a good level of education or a learned occupation, although none of the respondents had a child with congenital hydrocephalus. This study is similar to previous studies about the knowledge of congenital hydrocephalus and other birth defects among mothers, as the knowledge remains higher among the learned and those with a higher socioeconomic status, and poorer among the illiterates and those with low socioeconomic status.

The findings of this study show that more public enlightenment campaigns should be embarked on to increase the public awareness on congenital hydrocephalus and its associated risk factors. More emphasis should be made about congenital hydrocephalus and other birth defects during health talks in antenatal and prenatal clinics, especially avoidable factors in the maternal environment that potentially confer an increased risk of congenital hydrocephalus development. This would be a critical step in preventing some of these cases.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

FundingNone.

References

- Maternal environmental risk factors for congenital hydrocephalus: a systemic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41(5):E3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital hydrocephalus- an epidemiological study of maternal characteristics in a tertiary care center. . 2017;6(75):5393-5396. JEMDS

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of birth defects amongst nursing mothers in a developing country. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(1):180-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge of birth defects among nursing mothers in a developing country. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(1):180-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of congenital anomalies of the central nervous system in children in Enugu, Nigeria: a retrospective study. Ann Afr Med. 2016;15(3):126-132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Women’s knowledge, attitude and behavior about maternal risk factors in pregnancy. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145873.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of mothers on risk factors influencing pregnancy outcomes in Abeokuta South Local Government Area, Ogun State. Eur Sci J. 2015;11(11):313-324.

- [Google Scholar]