Translate this page into:

Acute Thoracolumbar Myelitis Secondary To Intrathecal Chemotherapy

Chen Fei Ng, MRCP Neurology Unit, Department of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre Jalan Yaacob Latif, Bandar Tun Razak, Kuala Lumpur 56000 Malaysia n.chenfei@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Lymphoma is known to cause a wide spectrum of neurological disorders, including local lymphomatous infiltration and paraneoplastic syndrome. More commonly, the neurological complications in patients with lymphoma are due to the use of chemotherapeutic agents. Chemotherapy-induced neurological syndromes encompass encephalopathy, seizures, arachnoiditis, cranial neuropathies, caudal equina syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy.1 We herein describe a young girl with lymphoma who developed acute myelitis following intrathecal chemotherapy.

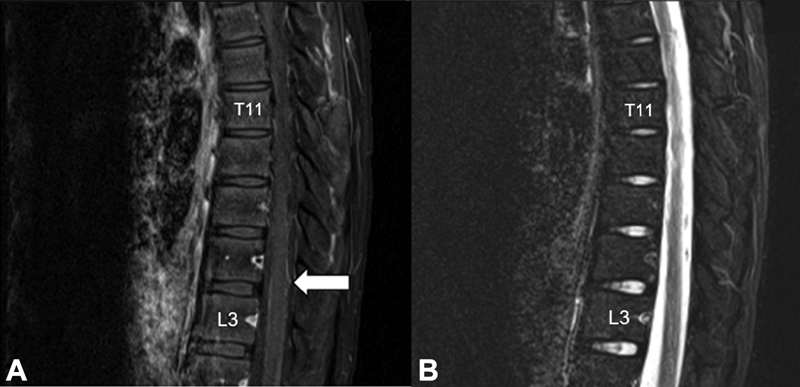

A 15-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of fever and neck swelling. CT scan of the thorax revealed large mediastinal mass, with extensive lymphadenopathies in the mediastinum, axilla and neck regions. Histopathology of mediastinal mass biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma. She was treated with chemotherapy regime containing cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone. Intrathecal methotrexate (MTX) and cytarabine arabinoside (Ara-C) injections were also given for central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis. Pretreatment cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable with no evidence of lymphomatous infiltration. Three days following her sixth intrathecal chemotherapy, she developed sudden onset of bilateral lower limbs weakness. Neurological examinations revealed flaccid paraparesis with muscle power of ⅗. There was a stocking distribution sensory loss up to the ankle level, which had been present since the early course of the chemotherapy. There were no upper extremities or cranial nerves' involvement. Onconeuronal antibodies were not detected. Nerve conduction study performed 5 days later showed a length-dependent sensorimotor axonal neuropathy secondary to vincristine use. CT brain and MRI of the lumbosacral spine were normal. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT of whole body showed complete metabolic response with tumor regression. She was treated as Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), with a course of intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin. However, the neurological condition progressed a further 2 weeks later where she developed worsening bilateral lower limbs' weakness and urinary retention. Muscle power of the lower limbs was ⅖ with bilateral extensor plantar reflexes. The repeated spine MRI revealed inflammatory changes in the lower thoracic and upper lumbar region (Fig. 1). She was treated as intrathecal chemotherapy-induced myelitis. A 5-day course of IV methylprednisolone was given, followed by a short course of oral prednisolone. Her condition gradually improved with rehabilitation. At 6-months follow up, she was able to ambulate with assistance and her lower limbs power improved to ⅘.

-

Fig. 1 Sagittal view of thoracolumbar MRI. T1-weighted postgadolinium sequence revealed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement in the lower thoracic and lumbar spinal cord with nodularity in the posterior aspect of the lumbar spinal cord (A). There was no intramedullary lesion seen on the T2-weight sequence (B).

Fig. 1 Sagittal view of thoracolumbar MRI. T1-weighted postgadolinium sequence revealed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement in the lower thoracic and lumbar spinal cord with nodularity in the posterior aspect of the lumbar spinal cord (A). There was no intramedullary lesion seen on the T2-weight sequence (B).

Intrathecal chemotherapy with MTX and Ara-C are routinely use for CNS prophylaxis alongside systemic chemotherapy in the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma. Spinal cord complications following intrathecal chemotherapy, although rare, may sometimes occur. Interestingly, the onset of myelopathy following intrathecal chemotherapy can be from few minutes up to a few months later.2 The clinical presentation can vary from transient paraparesis to permanent tetraplegia, with variable sensory deficit as well as bowel and bladder dysfunction. Intrathecal methotrexate may induce direct toxic effect or interferes with metabolic pathway of folates, potentially leading to spinal cord demyelination.3 However, the pathophysiology of myelopathy remains largely unknown. Higher risk of intrathecal myelopathy had been seen in patients who received high dose intrathecal MTX with repeated injection within short interval period, concurrent use with other intrathecal agents such as Ara-C, systemic chemotherapy or craniospinal irradiation.4 Corticosteroids were often used in chemotherapy-induced myelitis and variable improvement of symptoms have been reported.5

The diagnosis of chemotherapy-induced myelitis can be clinically challenging. The radiological changes of the myelitis may not be evident in mild cases or lag behind the clinical presentation as what was described in our patient. Nerve conduction study and electromyography are often ordered, but they may be misleading in patients with partial myelitis. Many patients showed a certain degree of background neuropathy due to vincristine use, which further clouds the diagnostic process. In this patient, the acute onset of paraplegia, clinical and radiological remission of lymphoma and negative onconeuronal antibodies made the possibility of paraneoplastic syndrome less likely. There were also no demyelinating features in the neurophysiological study to suggest acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy or GBS, although axonal variant could not be excluded. Nevertheless, the subsequent development of incontinence and extensor plantar responses clinched the diagnosis of myelopathy, which was then confirmed by repeated MRI of the spine. Clinical reassessment and lower threshold for neuroimaging are crucial in such cases. Early recognition of this complication is the key, as discontinuation of offending chemotherapeutic agents will prevent irreversible permanent neurological sequelae.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- Acute lumbar polyradiculoneuropathy as early sign of methotrexate intrathecal neurotoxicity: case report and literature review. Clin Case Rep. 2019;7(4):638-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myelopathy following intrathecal chemotherapy in adults: a single institution experience. J Neurooncol. 2015;122(2):391-398.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical and clinical aspects of methotrexate neurotoxicity. Chemotherapy. 2003;49:92-104. (1-2):

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer-treatment-induced neurotoxicity–focus on newer treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(2):92-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myelitis following intrathecal chemotherapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Case Rep Neurol. 2014;82(10):307.

- [Google Scholar]