Translate this page into:

When Mount Fuji Can Erupt after Seven Days: A Case Report of Delayed Posttraumatic Tension Pneumocephalus with Literature Review

G. Krrithvi Dharini III, MBBS Saveetha University, Saveetha Medical College and Hospital Thandalam, Chennai-600124, Tamil Nadu India krrithvidharini@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Tension pneumocephalus (TPC) is a neurosurgical emergency that occurs when there is an expansion of trapped intracranial gas causing raised intracranial pressure. Rarely, posttraumatic TPC can occur even after 72 hours although the initial scans are normal. There are less than 20 cases of delayed TPC in the reported literature. Here, we report a case of delayed TPC that occurred 7 days after the initial injury and presented as sudden neurological deterioration. It was promptly diagnosed with a computed tomography brain and appropriate surgical intervention was performed and the outcome was good. We also did a literature review of reported cases of delayed TPC and looked out for factors that may predict its occurrence. The occurrence of an episode of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, followed by worsening of headache and sensorium in a patient with anterior cranial fossa fracture should alert a neurosurgeon to the possibility of delayed TPC.

Keywords

traumatic tension pneumocephalus

delayed tension pneumocephalus

Introduction

Pneumocephalus (PC) is the presence of air or gas trapped within cranial cavity. It complicates approximately 3.9 to 9.7% cases of head injury.1 2 Most of it remaining asymptomatic, it is uncommon for PC to morph into tension pneumocephalus (TPC). TPC is a neurosurgical emergency that occurs as a result of increased intracranial pressure due to presence of intracranial air. TPC can be acute (<72 hours) or delayed (>72 hours), with delayed being even rarer.3 Although head injury is commonly attributed to the development of TPC, postoperative status, following chronic subdural hematoma accounts for 2.5 to 16% of cases.4 5 Other etiological factors include infections and postventriculoperitoneal shunt, or theco-peritoneal shunt.3 6 We describe a case of head injury following road traffic accident, where the patient developed TPC after 7 days of head injury. This case emphasized the importance of serial radiological evaluation and neurological assessment even in mild-to-moderate head injuries.

Case Report

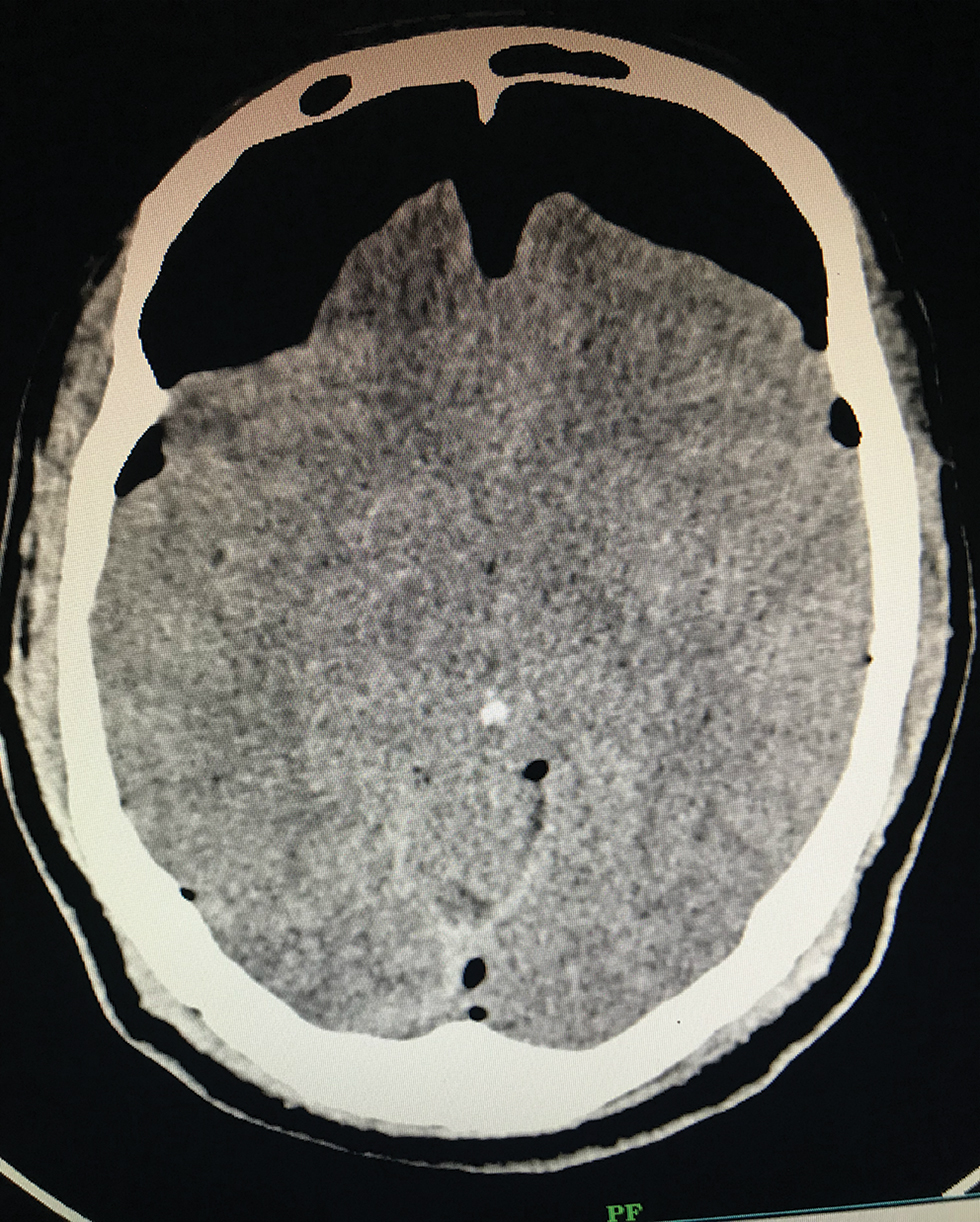

A 45-year-old male patient, with alleged history of road traffic accident under the influence of alcohol, was presented to the emergency department. Patient had a history of epistaxis and loss of consciousness for 10 minutes after which he recovered and had persistent mild headache. On examination, his Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15/15, decreased vision in the right eye with relative afferent pupillary defect of the right pupil. He was tested negative for other cranial nerves, sensory, or motor deficits. At the time of presentation, patient did not have cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea. Computed tomography (CT) brain and facial bones (Fig. 1) revealed multiple facial bone fractures involving inner table of frontal sinus, right zygomatic, and lateral wall of optic foramen. There was no evidence of brain parenchymal injury or PC. A postinjury 24-hour follow-up scan showed a small speck of PC in the frontal region. Magnetic resonance imaging brain with orbit revealed signal changes in the right optic nerve. Visual evoked potential suggested for right optic neuropathy, for which the patient was started on methylprednisolone.

-

Fig. 1 Computed tomography brain done on the day of admission.

Fig. 1 Computed tomography brain done on the day of admission.

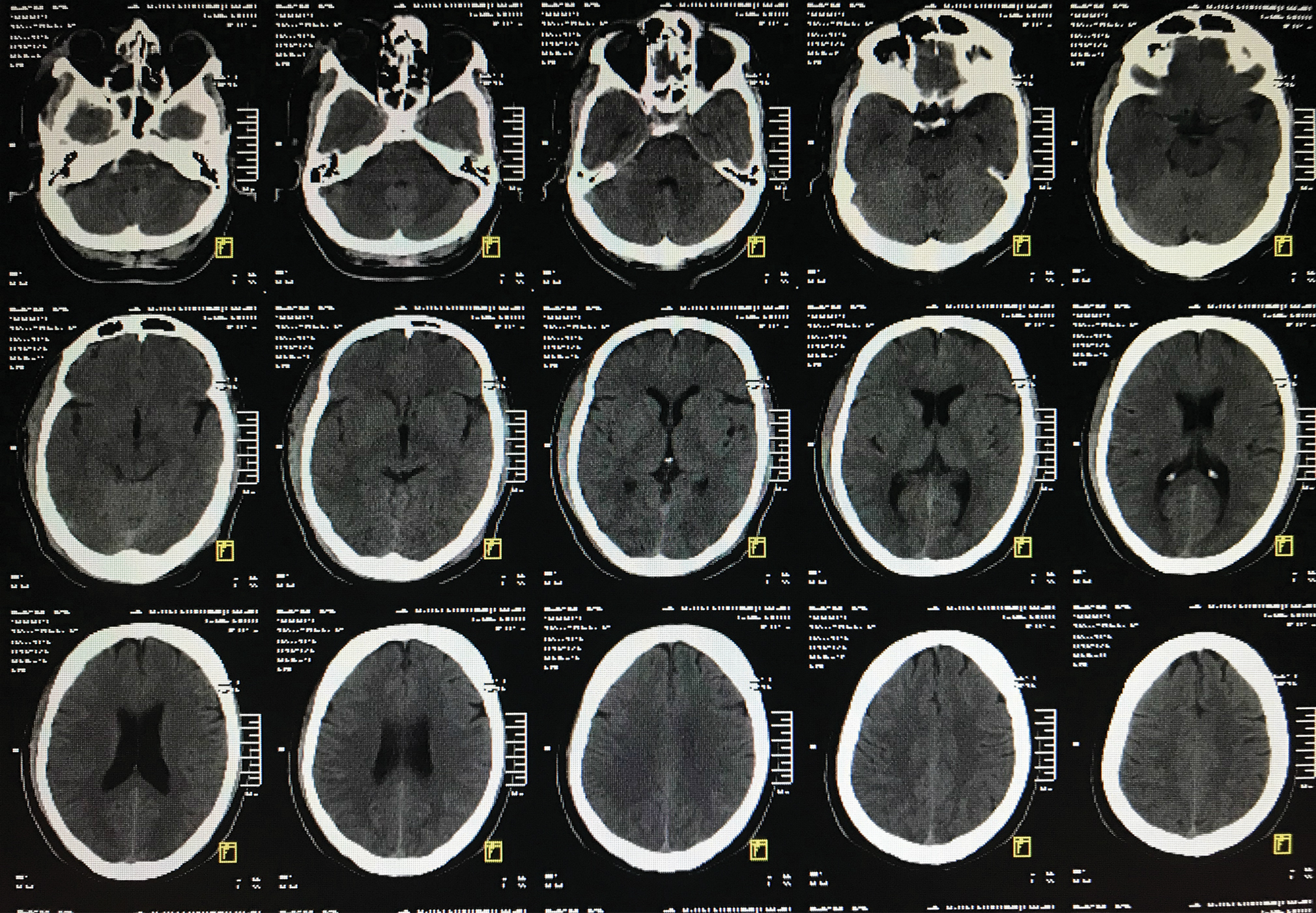

On postadmission day 6, he developed an episode of CSF rhinorrhea. On postadmission day 7, patient had worsening of headache with a drop in GCS of two points (13/15). Repeat CT brain (Fig. 2) revealed bifrontal TPC with classical Mount Fuji sign. Hence, the patient was subjected to emergency burr-hole and tapping and release of TPC. During the postoperative period, patient’s headache was relieved, GCS improved to 15/15, and he did not have further CSF rhinorrhea. Postsurgery scan showed resolution of TPC and the mass effect on the frontal lobes and ventricles was relieved. Patient had no further episodes of CSF rhinorrhea at 6 months of follow-up and his vision in the right eye improved significantly after a course of steroids. Currently, the patient is on regular follow-up with no significant complaints.

-

Fig. 2 Computed tomography brain done on seventh postadmission day.

Fig. 2 Computed tomography brain done on seventh postadmission day.

Discussion

Pneumocephalus was first described in 1741 by Lecat.7 In 1962, Ectors, Kessler, and Stern first reported a case of TPC.8 The two theories regarding the etiology of TPC are Dandy theory of ball valve mechanism and Horowitz theory.9 10

Dandy theory states that unidirectional flow of air through a defect and trapping of air within the cavity causes TPC. Horowitz explains that TPC is due to negative pressure within the cavity as a result of excessive loss of CSF (inverted soda bottle effect). In our case, these two theories might be the most probable pathophysiology.

Etiology of PC as reported in literature shows trauma, postsurgery, neoplasms, and infections. In a large prospective study conducted in level one trauma center by Paul tran et al., the incidence of PC was 0.77% (68/8747). Trauma contributed 81% (55/68), postsurgical 13% (9/68), tumor 1.5% (1/68), and presumed IV injection or idiopathic 4% (3/68).7 Hence, trauma is found to be the most common etiology of PC then follows postsurgical sequel.

The incidence of TPC is very rare, limited to case reports, and small case series. Delayed TPC is characterized by PC occurring 72 hours after injury. Some cases occur even later as described by Sprague11 and Poulgrain et al.12

The common manifestations noticed are headache, vomiting, CSF rhinorrhea, decreased vision, lethargy, and stupor progressing to coma leading to death. Diagnosis in most case was definitive with plain CT and by the characteristic Mount Fuji sign. This sign is characteristic of TPC. It appears as bilateral frontal subdural air on CT with widened interhemispheric fissure, representing the compression and separation of frontal lobes by subdural air. TPC can also occur without classical Mount Fuji sign and in any compartment of the brain.

Review of literature for previously reported cases of delayed TPC in the past 20 years has been documented in Table 1. Search was done using keywords TPC, posttraumatic and delayed in PubMed and Google Scholar.

|

Author |

Year |

Patient profile |

Clinical presentation |

Management |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviations: RTA, road traffic accident; TPC, tension pneumocephalus. |

|||||

|

Ruge et al |

1985 |

28/Male 7/Male |

Delayed TPC 11 days following shunt surgery Delayed TPC 1 week following shunt surgery |

Surgery Surgery |

Good Good |

|

Kon et al |

2003 |

46/Male |

Delayed TPC after 7 years of craniotomy |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Sankhala et al |

2004 |

19/Male |

Delayed TPC after 6 months of shunt surgery |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Hong et al |

2005 |

64/Male 38/Female |

Delayed TPC after ventriculoperitoneal shunt Delayed TPC after 12 years of trauma |

Surgery Surgery |

Good Good |

|

Kıymaz et al |

2005 |

63/Male |

Delayed TPC 11 days after RTA |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Chandran et al |

2007 |

18/Male |

Delayed spontaneous TPC |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Leong et al |

2008 |

42/Male |

Traumatic delayed TPC |

Conservative |

Good |

|

Lee et al |

2009 |

45/Male |

Delayed TPC caused by spinal tapping in a patient with basal skull fracture and pneumothorax |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Rathore et al |

2011 |

30/Male |

Delayed TPC 2 weeks after fall from vehicle |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Solomiichuk et al |

2013 |

75/Male |

Delayed TPC 5 days after open penetrating wound |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Kankane et al2 |

2016 |

30/Male |

Delayed TPC after 1 month of trauma |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Wang et al10 |

2016 |

25/Male |

Delayed TPC 16 weeks after bifrontal craniotomy for self-inflicted gunshot wound |

Surgery |

Good |

|

Chen et al |

2018 |

27/Female |

Delayed TPC 9 years after craniotomy |

Surgery |

Good |

In this case report, fracture involving the inner table of frontal sinuses, one of the most common associations with the development of PC apart from ethmoid sinus fracture led to unilateral flow of air based one the Dandy theory, producing PC. CSF rhinorrhea further created a negative pressure resulting in PC based on the Horowitz theory.

Tension pneumocephalus always warrants surgical intervention, as in this case, urgent decompression with burr-hole/needle aspiration. If TPC is diagnosed timely with appropriate intervention, the outcome is generally very good. Challenge of delayed TPC lies in the timely diagnosis, which only can be attained by regular clinical monitoring and obtaining a plain CT brain when required.

Conclusion

Regular assessment with standardized scales such as GCS in patient with neurotrauma is essential. CT is diagnostic of TPC. A sudden worsening of headache following CSF rhinorrhea in a posttraumatic patient even with previous normal CT should raise a suspicion of TPC.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- Traumatic tension pneumocephalus: two case reports. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;31:145-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posttraumatic delayed tension pneumocephalus: rare case with review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11(4):343-347.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traumatic tension pneumocephalus - two cases and comprehensive review of literature. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2017;7(1):58-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tension pneumocephalus as complication of burr-hole drainage of chronic subdural hematoma: a case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2010;1:27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-traumatic tension pneumocephalus: series of four patients and review of literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2016;26(2):302-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, radiographical features, and proposed mechanism for pneumocephalus from intravenous injection of air. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11(2):180-185.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ventriculopleural shunt procedure for hydrocephalus. Case report of an unusual complication. J Pediatr. 1962;60:418-420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial pneumatocele: an unusual complication following mastoid surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1964;78:128-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delayed tension pneumocephalus following gunshot wound to the head: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Surg. 2016;2016:7534571.

- [Google Scholar]