Translate this page into:

Innovation in Community Psychiatry for the Delivery of Mental Health Services: The Sawangi Model

Prakash B. Behere, MBBS, MD (Psychiatry), FAMS, FIIOPM Department of Psychiatry, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Sawangi (Meghe) Wardha 442107, Maharashtra India pbbehere@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Objectives Can undergraduate medical students (UGs) adopt a village model to identify mentally ill persons in an adopted village successfully?

Materials and Methods UGs during their first year adopt a village, and each student adopts seven families in the villages. During the visit, they look after immunization, tobacco and alcohol abuse, nutrition, hygiene, and sanitation. They help in identifying the health needs (including mental health) of the adopted family. The Indian Psychiatric Survey Schedule containing 15 questions covering most of the psychiatric illnesses were used by UGs to identify mental illness in the community. Persons identified as suffering from mental illness were referred to a consultant psychiatrist for confirmation of diagnosis and further management.

Statistical Analysis Calculated by percentage of expected mentally ill persons based on prevalence of mental illness in the rural community and is compared with actual number of patients with mental illness identified by the UGs. True-positive, false-positive, and true predictive values were derived.

Results In Umri village, UGs were able to identify 269 persons as true positives and 25 as false positives, whereas in Kurzadi village, UGs were able to identify 221 persons as true positives and 35 as false positives. It suggests UGs were able to identify mental illnesses with a good positive predictive value. In Umri village, out of 294 mentally ill patients, it gave a true positive value of 91.49% and a false positive value of 8.5%, whereas in Kurzadi village, out of the 256 mentally ill patients, it gave a true positive value of 86.3% and a false positive value of 13.67%.

Conclusion The ratio of psychiatrists in India is approximately 0.30 per 100,000 population due to which psychiatrists alone cannot cover the mental health problems of India. Therefore, we need a different model to cover mental illness in India, which is discussed in this article.

Keywords

mental illness

rural mental health

undergraduates

village adoption

Introduction

Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College (JNMC) was established in 1990 under Nagpur University, later Maharashtra University of Health Sciences, Nashik, and, finally, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences and was granted the status of a Deemed to be University by the University Grants Commission in 2005. It was accredited with an “A+” grade by the National Assessment and Accreditation Council, which is an autonomous body set up by the University Grants Commission. The intake capacity of undergraduate is 250 students from 2019. The college is based in the central part of India and caters predominantly to the rural population. The vision of the university is to emerge as a global center of excellence in the best evidence-based higher education encompassing a quality centric, innovative, and interdisciplinary approach, generating refutative research and offering effective and affordable health care for the benefit of the mankind.

As the institute is in a rural area, its policy and planning are more community-oriented and community care based. When it comes to the planning of mental health, there are many approaches to the delivery of mental health care services in India.1 One of the models is the 1982 National Mental Health Programme (NMHP).2 The formulation of the Mental Health Program was an important event in the history of mental health care. The principle aim of the NMHP is “to ensure availability of minimum mental health care for all in the foreseeable future, particularly to the most vulnerable and underprivileged sections of the population.” While working in a rural area in the central part of India, an innovative approach was adopted to assess its success and failure.

Even late Prime Minister Mrs Indira Gandhi rightly pointed out the following while addressing the World Health Assembly in 1981: “In India we would like health to go to homes instead of large number gravitating towards centralize hospitals. Services must begin where people are and where problem arrives.” This statement was path-breaking in community health.

In view of the preceding statement, various approaches were tried for community care of mentally ill patients. One method of extension of mental health care in the rural community is the camp approach. This holds good for the problems associated with drug dependence, particularly of substances that have enjoyed a historically wide sociocultural sanction (e.g., alcohol) and require nonclinical and noninstitutional approaches. An important innovation is to alter the pattern of care from the hospital to the community and to change the de-addiction procedure into a community activity. This method has been demonstrated to be quite successful in problematic use of both opium and alcohol.1 3 4 5 6 The second approach is outreach and extensive programs. The third one is this innovative model, which we are going to discuss.

Materials and Methods

Village Adoption

Undergraduate medical students (UGs) during their first year adopt a village, and one student adopts seven families in the villages.

-

First-year UGs: All first-year students, the batch of 2019, adopted Nachangaon village in county Wardha, Maharashtra, India. Every student identifies the families. Each student adopts six to seven families. They visit the village every Saturday.

-

Second-year MBBS: The batch of 2018 also adopted Nachangaon village, and every student adopts six to seven families each. They visit the village every third and fourth Saturday of the month.

-

Third-year MBBS: The batch of 2017 was divided into two groups. One group adopted Umri (Meghe) village, whereas the other group adopted Kurzadi village. Every student adopts five to six families each. They visit the families every first and second Saturday of the month.

They are given a semi-structured notebook (journal) to complete while they are undergraduates. During the visit, they look after immunization, tobacco and alcohol abuse, nutrition, hygiene, and sanitation. They help in identifying the health needs (including mental health) of the adopted family.

They also give due attention to antenatal care, chlorination of water, proper drug compliance, and many more health-related issues. The semistructured notebook contains interview schedule for mental health as well. It deals with adolescent mental health and mental health education. The students revisit the families and participate in their care once a month over the next 4½ years during their undergraduate career. Students make frequent visits to these patients if they are hospitalized and extend all possible help. After discharge, they look after drug compliance and ensure regular follow-up.

During monthly visits, they meet the family members and patients and enquire the about following:

-

Whether the patient is taking medicines regularly as prescribed?

-

How much improvement has he/she made?

-

Has he/she developed any side effects with drug use?

-

Whether the patient has started working again?

-

Whether the patient is keeping up appointments for follow-up and review?

Students become socially closer to these families. Whenever family members encounter health problems, they visit students for help in the hospital. Thus, these students liaise with hospital and their patients.

Apart from professional interaction, there is great social interaction between the student and his/her adopted family. They extend invitation to each other for marriage and so on. We added a few questionnaires for easy identification of mentally ill persons in the community, which is the Indian Psychiatric Survey Schedule.6 This has 15 questions covering most of the psychiatric illnesses.7

Statistical Analysis

Calculated by percentage of expected mentally ill persons based on prevalence of mental illness in the rural community and is compared with actual number of patients with mental illness identified by the UGs. True positive, false negative, and true predictive values were derived.

Interventions and Initiatives

Specifically, the following activities are taken up by the students for adopted families to meet needs such as humanizing institutions, early recognition and treatment, support to families of mentally ill persons, rehabilitation, public awareness, drug dependence care, and suicide prevention.

-

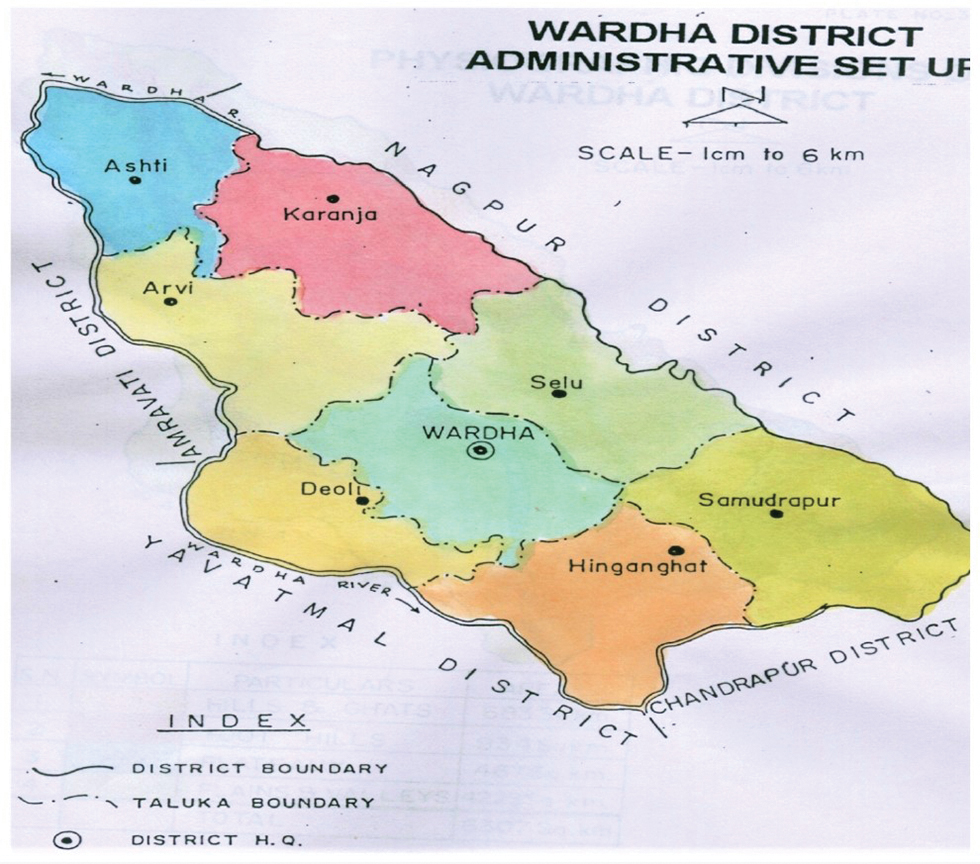

Fig. 1 Map of Wardha District.7

Fig. 1 Map of Wardha District.7

Results

Table 1 shows population, number of families, age distribution in the villages Umri and Kurzadi.

|

Details |

Umri |

Kurzadi |

|---|---|---|

|

Total families |

385 |

320 |

|

Total population |

1640 |

1416 |

|

Adult population |

1471 |

1281 |

|

Age < 1 y |

36 |

22 |

|

Age 1–4 y |

58 |

46 |

|

Age 5–15 y |

75 |

67 |

Table 2 shows the expected population suffering from mental illness, taking 20% as the prevalence rate in India.

|

Details |

Umri |

Kurzadi |

|---|---|---|

|

Abbreviation: UG, undergraduate medical student. Note: Taking 20% as the prevalence rate for psychiatric illness, the total number of villagers suffering from psychiatric illness in Umri village is 294 and in Kurzadi village it is 256. This shows that they could identify only 91.49% cases in the community (true positive); therefore, the remaining 25 cases they have taken as normal were missed (false negative: 8.50%). |

||

|

Total number of persons with psychiatric illness |

294 |

256 |

|

UGs could identify mentally ill persons |

269 |

221 |

|

True positive |

269 (91.49%) |

221 (86.32%) |

|

false negative |

25 (8.50%) |

35 (13.67%) |

In Umri village, UGs were able to identify 269 persons as true positives and 25 as false negatives, whereas in Kurzadi village, they were able to identify 221 as true positives and 35 as false negatives. It suggests that UGs were able to identify mental illnesses with a good positive predictive value. In Umri village, out of 294 mentally ill patients, it gives a true positive value of 91.49% and a false negative value of 8.5%, whereas in Kurzadi village, out of the 256 mentally ill, it gives a true positive value of 86.3% and a false negative value of 13.67%.

Table 3 shows the diagnostic breakdown of psychiatric illness that the UGs were able to identify in both villages. In both villages, somatoform disorders followed by depression were the most common psychiatric illnesses identified by UGs. Both villages had an almost similar prevalence of all mental illness with the exception of seizure disorder, whose prevalence was sevenfold higher in Umri village as compared with Kurzadi village.

|

Diagnosis |

Umri |

Kurzadi |

|---|---|---|

|

Somatoform disorder |

109 |

87 |

|

Depression |

71 |

62 |

|

Alcohol dependence |

60 |

55 |

|

Seizure disorder |

15 |

2 |

|

Psychoses |

12 |

14 |

|

Mental retardation |

2 |

1 |

Discussion

The ratio of psychiatrists in India is approximately 0.30 per 100,000 population.8 This suggests that only psychiatrists alone cannot cover the mental health problems of India. Due to the limited numbers of psychiatric manpower, this approach will be very useful. This model can be replicated all over the world in developing countries with limited psychiatrists.

We have this innovation of community psychiatry for the delivery of mental health services. JNMC trains doctors and nurses with rural exposure and innovations in the field of medical education and rural health care.

As far as the adoption of village model is concerned, there is no literature available. In Holland, the medical students adopt one chronic schizophrenia patients for 4½ years and regularly follow up and look after drug compliance.9 Another medical college that has been adopting a similar type of model since many years is Mahatma Gandhi Medical College, Sewagram, Maharashtra, India.

The effectiveness of this model will be known in a few years’ time, and we have a long way to go.

Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

There are some limitations of this study. Most importantly, we could not compare our study with similar studies, as they are not available. UGs have not adopted a village except in Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sewagram where a similar model was used for other health issues such as vaccination, hygiene, nutrition, and diet. Further long-term follow-up is needed for a clear picture and utility of such type of model in the future.

Conclusion

The District Mental Health Program (DMHP) was launched in the year 1996 (in the ninth 5-year plan) in four districts under the NMHP.10 Now, it has developed to include 123 districts under the 12th 5-year plan. DMHP has been highly successful in providing mental health care to the community at least on the district level. However, providing mental health care beyond the district level has been very difficult. In this program, either a trained psychiatrist or a general duty medical officer is provided training for early identification of mental illness and its management.

The Rural Unit for Health and Social Affairs (RUHSA)–A Rural Community Health Care Program is run by Christian Medical College, Vellore, India, since 1977 to develop a model rural health care center primarily focused on rural health (maternal, child health, infectious diseases, and dental problems), poverty alleviation, and so on. It also covers community-based rehabilitation program for mentally and physically challenged individuals.11

In our Sawangi model, as a part of training, UGs of medical school are able to identify and screen out successfully mental illness in villagers. In villages, no psychiatrists are available in India currently.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to all undergraduate students of JNMC who took a keen interest in this study with special reference to rural mental health for the identification of cases.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Murthy RS ,Rural and Community Psychiatry, Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry. Available at: http://www.indjsp.org. Accessed July 22, 2020

- National Health Mission. National Mental Health Programme (NMHP). Available at: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=2&sublinkid=1043&lid=359. Accessed July 22, 2020

- Khurana H, Kumar P, Vohra AK. Evaluation of psychiatric referral in multidisciplinary camp. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society, January 9–12, 2001, Pune, India

- https://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/maharashtra/districts/wardha.htm. Accessed July 22, 2020

- Number of psychiatrists in India: baby steps forward, but a long way to go. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(1):104-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- Havnaar JM. (2000). Adoption of one schizophrenic patient each by medical students in Holland (personal Communication)

- District Mental Health Program - Need to look into strategies in the era of Mental Health Care Act, 2017 and moving beyond Bellary Model. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(2):163-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandy S. Available at: https://www.cmchvellore.edu/WeeklyNews/othernews/LT2014/awards/pdf/ruhsa.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2020