Translate this page into:

Impact of Stroke on Quality of Life of Stroke Survivors and Their Caregivers: A Qualitative Study from India

Parmeshwar Satpathy, MBBS, MD, DNB Department of Community Medicine, Veer Surendra Sai Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Ayurvihar, Burla, Odisha 768017 India drparamsatpathy@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

Objectives Stroke is a significant global public health challenge attributable to an array of disabilities it causes alongside an impairment in cognition. The monetary impact of stroke care includes acute treatment expenses as well as outrageous expenses of postdischarge chronic hospital care and rehabilitation services. The current study aimed to study the perceptions along with experiences of stroke survivors and caregivers.

Materials and Methods In-depth interviews (IDIs) of stroke survivors and their primary caregivers were conducted at their home 2 months after their discharge from the hospital in Bhopal, India. These IDIs were later analyzed.

Results The following eight themes emerged: pervasive and irreversible, multifunction loss and dependency, holistic impact on the health of person and family, money and matter, nonaccommodative cost and baffled belief, professional paralysis, social crisis, and slow and obscured progress. The added obligation of taking care of a disabled stroke survivor along with adjusting their own lifestyle with financial apprehensions, worry about future, prolonged hours of care, and stress are major factors that increase the burden of the caregivers.

Conclusion Caregivers should be sensitized with proper counseling and training through health care institutions to ensure appropriate care and management of stroke survivors at home, as it will also help in addressing their psychosocial needs, and minimizing the knowledge gap, doubts and uncertainties about the disease and its aftereffects.

Keywords

stroke

quality of life

qualitative

caregivers

framework analysis

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).1 Low- and middle-income countries account for approximately 75% of global stroke deaths and 81 percent of stroke-related disability.2 India accounts for nearly 14% of global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost due to stroke.3 Stroke is one of India's leading causes of morbidity and mortality, with an estimated adjusted prevalence rate of stroke ranging from 84 to 262 per lac in rural areas to 334 to 424 per lac in urban areas.4 According to recent population-based research, the incidence rate of stroke in India is 119 to 145 per lac.5

Stroke is a significant global public health challenge attributable to the array of disabilities it causes alongside an impairment in cognition. Stroke survivors face a huge burden due to the chronic disability that ensues.6 Disability caused by stroke has a massive impact on the patient, as it not only leaves them with physical disabilities but also hampers their social lives massively.7 Poststroke depression not only affects the survivors themselves but also affects family and friends significantly.8 9 10 11 Previous research has shown that there is deterioration in the quality of life (QOL) among stroke survivors.12 13 14 15 16 17 18

A caregiver is someone who resides with the patient and is concerned with their care and nursing the most. Caregivers' not only help the stroke survivors in dealing with their limitations such as physical (walking), nursing (cleaning, feeding, using toilet), communication, psychological and emotional variations but also have to make several adjustments in their daily schedule. If the caregiver is the earning member of the family, then on most occasions, they have to compromise from their job to provide care to the Stroke survivor leading to significant economic burden on the family. This, in turn, develops anxiety and uncertainty among both.19

The monetary impact of stroke care includes acute treatment expenses as well as outrageous expenses of postdischarge chronic hospital care and rehabilitation services. Stroke survivors' mortality rates and hospital discharge rates do not accurately reflect their level of disability, which is borne mostly by the patients and their caregivers.20

The unbiased assessment of physical impairments is not adequate for assessing stroke outcomes; besides, measuring the QOL is essential to present a more reliable and fuller picture of the poststroke level of disabilities.21 Qualitative methods are more appropriate if patients' and caregivers' experiences are to be more fully understood.

While stroke is a disease that can significantly impact QOL, there is scant evidence available about the stroke survivors' and caregivers' feelings and QOL following stroke. Hence, this research was conducted to assess the impact of stroke on QOL of stroke survivors and their caregivers.

Materials and Methods

The current study was cross-sectional, using a qualitative method. The current study aimed to study the perceptions along with experiences of stroke survivors and caregivers, with a purposeful sampling design. Patients who experienced their first ever episode of stroke and were admitted to a tertiary care hospital in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India, were recognized and enlisted. Stroke survivors alongside their caregivers were visited following 2 months of discharge from the hospital. The study was conducted from October 1, 2014, to March 31, 2015. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical committee Gandhi Medical College Bhopal, and informed consent was taken from all participants.

In-depth interviews (IDIs) of stroke survivors and their primary caregivers were conducted at their home 2 months after their discharge from the hospital. An interview guide was prepared beforehand, which is shown in Table 1. The stroke survivors were encouraged and prompted to talk in-depth about the different problems they came across after developing the chronic debilitating condition and how they were coping with the same. Caregivers were enquired about various problems that they have come across while taking care of the stroke survivors, and how it is affecting them. We also tried to understand how caregivers cope with the various problems they face while caregiving.

|

For stroke survivors |

|

1) In terms of recovery, has the stroke left you with any problems? (Probe—mobility, language, vision and other routine activities) |

|

2) How do you take care of yourself? (Probe—Do you need anyone's help? For which activities do you require help?) |

|

3) How is the family support that you are receiving? (Probe—personal care, financial and emotional support) |

|

4) What do you do in your daily routine, as compared with before the event? |

|

5) Do you move out of your home? (Probe—social role) |

|

6) What all treatments are you currently on? (Probe—adherence to treatment, rehabilitation, physiotherapy and follow-up visits) |

|

7) How has this (stroke) affected your job? Are you often on leave now? |

|

For caregivers |

|

1) What do you know about the patient's disease? (Probe—bed sore, home based physiotherapy, feeding, any neurological symptoms and signs, drug administration?) |

|

2) What problems are you facing in taking care of the patient? (Probe—sense of burden, social life, family issues) |

|

3) What is your occupation, and while taking care of the patient, how is your job getting affected? |

|

4) Do you see any change in the patient's health? If there is no change, what could be the reasons? |

Data Collection Process

The first author conducted the IDIs with the stroke survivors and their caregivers at their homes, as it was comfortable for the respondents. After interviewing 12 patients (and their respective 12 caregivers), it was observed that no additional information was likely to be gained (data saturation was observed). Few preliminary questions were asked at the beginning of IDIs to serve as an ice breaker between the researcher and the participant. IDIs of caregivers were conducted in case of stroke survivors who had communication deficits. In such cases, caregivers were interviewed twice. Interviews were conducted on the same day for both stroke survivors and caregivers. The influence of one interview over the other was managed by having different interview guides for them, and conducting their interview in different rooms.

All the IDIs were conducted in Hindi, as the study participants were well versed in the same. Each interview lasted for 30 to 45 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded using a mobile phone, following which they were transcribed verbatim by the researcher. Various social cues of the participants such as voice and body language were noted, as they provided valuable information that was used to strengthen the verbal answer provided by the participant.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were reviewed independently by two authors. Transcripts were assessed twice to identify the emerging codes. The codes were analyzed and assembled into patterned categories that were derived either from the data or could likewise be identified as deduced from the literature in framework analysis. Subsequently, a theme was derived from the data, using the thematic analysis framework. In this manner, data analysis was repeated until no new themes emerged, and all the relevant text was coded.

Framework analysis was given preference above grounded theory in the current study, and an interview guide with a probe for patients and their caregivers was prepared beforehand. Utilizing the framework approach, few of the themes arising from the data were the identified issues included in the interview guide. Our data affirmed their importance, in this situation, and enabled to explore them further. With accumulation of data, many themes and categories emerged, which required refining and development. Utilizing framework analysis, indexing was followed by mapping and charting. Further, a framework analysis of the selected data was done, which followed five key stages: familiarization, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation.22

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the stroke survivors and caregivers are shown in Table 2, where we found majority of stroke survivors (ten) were male, while majority of caregivers were female (nine). The average age of the stroke survivors was 62.08 years, while that of caregivers was 32.5 years. All the females among the stroke survivors were homemakers, while the males were government employees, private employees, businessmen, farmers, or retired. Most of the female caregivers were homemakers, whereas all the males were daily laborers. Many stroke survivors were illiterate (five), while the others had attended school. One of the caregivers was illiterate, while most of them had attended school.

|

S. no. |

Age |

Gender |

Marital status |

Occupation |

Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

50 |

Male |

Married |

Government employee |

Intermediate |

|

2 |

80 |

Male |

Married |

Business |

Illiterate |

|

3 |

65 |

Male |

Widower |

Business |

Middle school |

|

4 |

75 |

Male |

Widower |

Retired |

Intermediate |

|

5 |

70 |

Male |

Married |

Retired |

Illiterate |

|

6 |

65 |

Female |

Married |

Homemaker |

Illiterate |

|

7 |

50 |

Male |

Married |

Private employee |

Primary school |

|

8 |

56 |

Male |

Married |

Farmer |

Middle school |

|

9 |

50 |

Female |

Married |

Homemaker |

Illiterate |

|

10 |

74 |

Male |

Married |

Private employee |

Intermediate |

|

11 |

70 |

Male |

Widower |

Private employee |

Illiterate |

|

12 |

40 |

Male |

Married |

Business |

Primary school |

|

Sociodemographic characteristics of the caregivers |

|||||

|

S. no. |

Age |

Gender |

Relation with patient |

Occupation |

Education |

|

1 |

46 |

Female |

Wife |

Homemaker |

Primary school |

|

2 |

28 |

Female |

Daughter-in-law |

Homemaker |

Primary school |

|

3 |

24 |

Female |

Daughter-in-law |

Homemaker |

Intermediate |

|

4 |

34 |

Female |

Daughter-in-law |

Homemaker |

Graduate |

|

5 |

34 |

Male |

Son |

Daily laborer |

High school |

|

6 |

27 |

Male |

Son |

Daily laborer |

Primary school |

|

7 |

37 |

Female |

Daughter |

Homemaker |

Graduate |

|

8 |

42 |

Female |

Wife |

Homemaker |

High school |

|

9 |

29 |

Female |

Daughter-in-law |

Homemaker |

Graduate |

|

10 |

24 |

Male |

Son |

Daily laborer |

Illiterate |

|

11 |

28 |

Female |

Daughter-in-law |

Homemaker |

Graduate |

|

12 |

37 |

Female |

Wife |

Homemaker |

Graduate |

Although almost all the members of the family, directly or indirectly, played a pivotal role in taking care of the patient, we have considered the family member who was actively involved in taking care of the patient as the primary caregiver of the patient. In our study, we found that majority of primary caregivers were women. Twenty-four such stroke survivors along with their primary caregivers were identified, and their IDIs were conducted to analyze the impact of stroke on the QOL of patients and their caregivers. These IDIs were later analyzed, where the following themes emerged.

Pervasive and Irreversible

Chronic debilitating diseases such as stroke create an unwelcome influence on stroke survivors' and caregivers' practices, and its perceived aftereffects on patients have multidimensional impacts, ranging from mental fragility, physical disability to financial concerns, and discouragement about future which, in turn, affects the whole family.

Hopelessness was evident in the response by a 65-year-old male patient, who expressed, “I feel the tension of the fact that if my hands and legs do not work, what will I do.” Echoing similar feelings another patient responded, “I don't see any hope now.”

Tension and concern were evident from responses of the stroke survivors, one of whom said, “now one hand is as good as broken and one leg is broken, what is left in my life?” Similarly, concerns about the irreversibility of the condition were raised by another 70-year-old male stroke survivor who reiterated, “not expecting that my condition will improve.”

Multifunction Loss and Dependency

Stroke disturbs the functioning of the body at optimum capacity. The main concern of survivors was the impairment of motor functions: being disabled, losing strength, encountering trouble in performing one's own task, and requiring assistance. This anxiety, in turn, generates a feeling of worthlessness, helplessness and dehumanization.

Stroke has left people with multiple motor disabilities; one of the patients stated, “there is a problem with my right hand and leg, and I am not able to walk due to the same.”

Another 74-year-old male patient experiencing a sense of dependency reiterated the same fact by narrating, “earlier I used to eat by myself, now I have to ask these people to help me in the same.”

Poststroke disability influences activities of daily living (ADLs), as the requirements of a stroke survivor fluctuate from physical (strolling, movement from bed to seat, seat to the toilet) to nursing (feeding, changing garments), etc. This creates a big challenge, on a daily basis, for caregivers, emanating from prolonged caring hours that cause inconvenience to the caregiver.

One of the caregivers who was the daughter-in-law of an 80-year-old male patient remarked, “he is not able to move his limbs; we make him bath and brush.” “She is unable to do anything, even not able to speak, we have to take care of her eating, toilet, and bathing,” another caregiver reiterated the same fact.

The problem in communication (verbal and nonverbal) leads to indecipherability and improper interaction with family members and friends. “She has a problem in talking, we do not understand what she is saying,” echoed one of the caregivers, son of a 65-year-old female stroke survivor.

Holistic Impact on the Health of Person and Family

Stroke survivors consider themselves to be a burden to the family. Such a perspective is evident from responses from one 65-year-old stroke survivor who narrated, “fix me so much that I don't have to be a burden on anyone.”

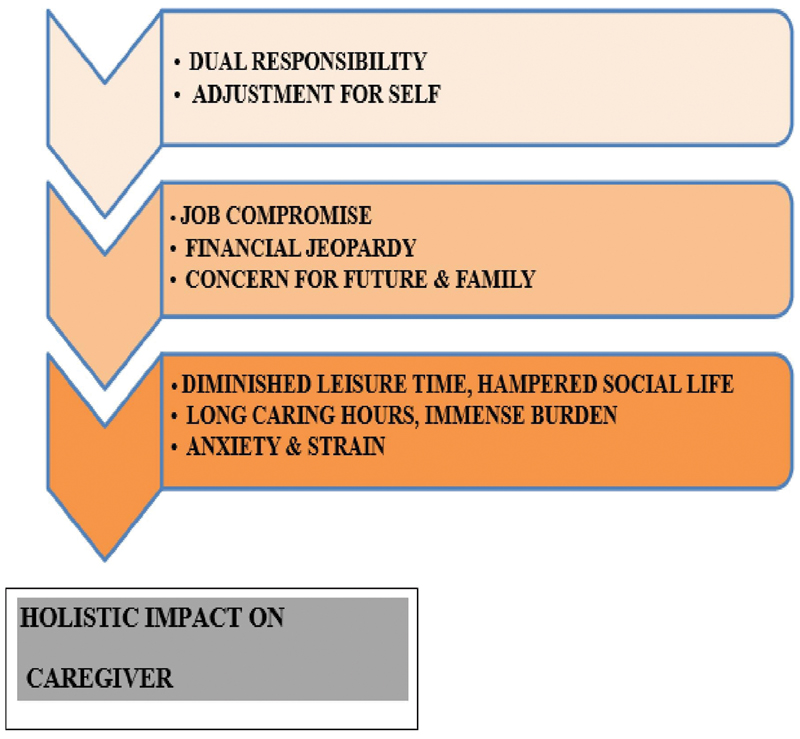

The added obligation of taking care of a disabled stroke survivor along with adjusting their own lifestyle with financial apprehensions, worry about future, prolonged hours of care, and stress are major factors that increase the burden of the caregivers.

“While taking care of him, I have also got irritable, I have also got blood pressure issues, he does not allow me to sleep overnight,” expressed the wife of a 50-year-old male patient, corroborating the same.

Psychosocial impact on family members is evident from the responses of the wife of one of the stroke survivors who narrated, “the children are unable to read; they cannot even sleep due to his problems.”

The deep impact on health can be ascertained from the responses of the caregivers; a 34-year-old caregiver son of a stroke survivor expressed, “I had to sell one goat to get him treated.”

Anxiety and strain was easily noticeable from responses of the caregivers, one of whom narrated, “we are in very bad shape, neither we can eat properly nor sleep properly.”

Money and Matter

Stroke survivors were mostly getting assistance in executing ADLs and financial help from family, but evidence of emotional support was lacking.

Various family members donned the role of caregivers in performing ADLs as is evident from the response of an 80-year-old stroke survivor who expressed, “my daughter-in-law takes care of me.” Financial support from family was unmistakably noticeable from the responses of stroke survivors. “My brothers are supporting me financially,” narrated a 74-year-old male patient.

Lack of emotional support can be exemplified from the following quotes of caregivers: “We take care of him else who will do it.” “We are facing problems but still we have to do it.”

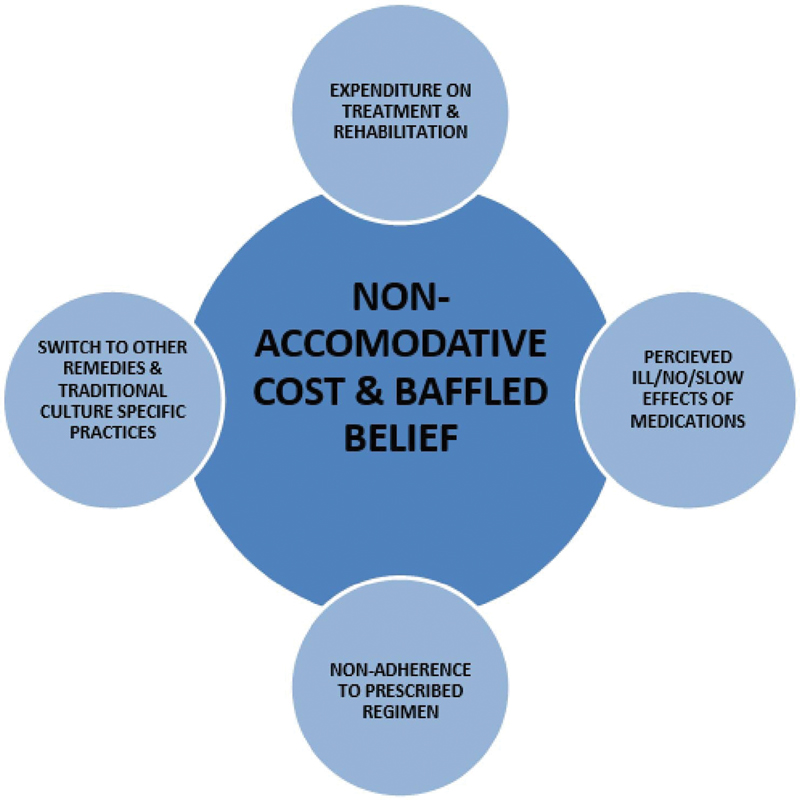

Nonaccommodative Cost and Baffled Belief

The uncertainty associated in the long run and chronicity of poststroke events lead patients and families to switch to other treatment remedies. Also, demanding costs of drugs, physical rehabilitation, and perceived ineffective medications cause loss of patients' and caregivers' hope in care and cure.

Many patients and caregivers perceived that the medications prescribed to them had side effects. This is clear from the response of a 74-year-old male patient who remarked, “it was getting hot due to medicines; sleep was also not possible.”

The economic burden on the family affected the physical rehabilitation of the patients. The same fact was exemplified from the following quotes of caregivers:

“Had to stop physiotherapy due to money problems.”

“As the physiotherapist asked for 200 to 300 rupees per day, then we could not do it due to lack of money.”

Belief in alternative therapies was evident from the responses of the caregivers. One of them narrated, “after discharge, we took him for treatment from traditional healers.”

Professional Paralysis

Restricted mobility and cognition affect vocation in terms of reduced interest and ability in pursuing the job. A feeling of worthlessness was visible from the remarks of a 75-year-old male patient who expressed, “no chances of getting any job, what else will happen when a person is bedridden.”

Chronic disability due to stroke leads to vocational impairment. “My business is ruined,” reiterated a 40-year-old male patient.

Stroke also has a major impact on the profession of caregivers. One of the caregivers expressed, “it has been 20 to 22 days I could not go to work.”

Social Crisis

Physical limitations meddle with the social life of stroke survivors and caregivers, as this leads toward compromised leisure time which adds to the emotional and moral catastrophes. Lack of mobility affects social life in a significant way. A 56-year-old male patient remarked, “cannot go out anywhere, how can I go?”

Cognitive impairment acts as a major hurdle in the social interaction of the patients. One of the caretakers who is the daughter-in-law of a 50-year-old female patient narrated, “when people come to meet her, she does not recognize anyone, also does not talk to anyone.”

The stroke survivors undergo emotional turmoil, leading to sudden outbursts of emotions. “When someone comes to meet him, he starts crying,” expressed one of the caregivers.

Slow and Obscured Progress

Slow and little progress in due course is perceived as intolerable and irreversible. This further aggravates hopelessness, helplessness, and worthlessness among stroke survivors as is evident from the following quotes of stroke survivors:

“Age is also on the higher side; health doesn't get any better at this age.”

“I do not feel any improvement in my condition, I do not think I will get cured with medicines.”

Caregivers also expressed similar opinions. “I do not think he will get any better, as he does not have the will power,” suggested a 37-year-old daughter of a stroke survivor.

The findings of this qualitative study on assessing the impact of stroke on QOL of stroke survivors and their caregivers are further illustrated by discourse analysis in the form of figures (Figs. 1 2 3).

-

Fig. 1 Discourse analysis on multidimensional impact of illness on stroke survivors.

Fig. 1 Discourse analysis on multidimensional impact of illness on stroke survivors.

-

Fig. 2 Effects on quality of life of caregiver.

Fig. 2 Effects on quality of life of caregiver.

-

Fig. 3 Discourse analysis on factors affecting course of treatment and rehabilitation.

Fig. 3 Discourse analysis on factors affecting course of treatment and rehabilitation.

Discussion

In the present study, the inductive approach was mostly followed, using qualitative methods, basically working from the bottom-up, utilizing participants perspectives to develop broad themes, and generating a theory which interconnected the themes. Point of view based on experience, perception, or observation is best expressed inductively. The researcher himself was a tool for collection of data, interpretations of which depends on researcher's lens. Words of the participants were analyzed by looking for common themes and paying attention to persuasive language.

Various quantitative parameters show the severity and effects of stroke in terms of physical dimensions; however, subjective feelings like emotional trauma and impairment in QOL may not be very well-addressed by the quantitative scales which are being revealed here by qualitative methodology. This study has provided insights into patients' and caregivers' experiences about the effects of stroke on QOL. Multifunctional loss and dependency create a sense of dehumanization for the stroke survivors.

Problem in communication (verbal and nonverbal) leads to indecipherability and improper interaction of stroke survivors with family members and friends. Failure to maintain or reestablish social ties seems to be an important determinant of poor QOL in survivors' life events and self-care necessities. Angeleri et al, through their research work on stroke, provided emphasis to the role of social and family support in good functional outcome.9 Consistent to the findings in the current study, a research from south India revealed that the functional disability of stroke patients led to a decrease in their social capacity as well.7

Restricted mobility and cognition affect vocation in terms of reduced interest and ability in pursuing the job, and if the diseased is the only earning member of the family, the challenge to adhere to medications and rehabilitation increases manifold, with growing financial concerns for family's welfare. King et al in their work on QOL after stroke suggested that coping responses and outcomes are influenced by cognitive appraisals of the importance of illness and the ability to cope with stressful events.23 In another study by Dewilde et al, it was found that patients' QOL after a stroke is dictated by their disability, level of dependence on caregivers, and coping strategy.24

The added obligation of taking care of a disabled stroke survivor along with adjusting their own lifestyle with financial apprehensions, worry about future, prolonged hours of care, and stress are major factors that increase the burden of the caregivers. Several other studies have published similar results.19 23 25 26 The current study findings also argue the need for proper counseling and training for caregivers in skills necessary for the daily care of the stroke patients in their homes. Similar findings have been echoed by few other studies.20 27 Cheng et al, in their study, have observed that the training given to caregivers on problem-solving skills and stress-coping techniques had a positive impact on their results.28 In another study by Nunes et al, it was observed that timely and personalized discharge planning of the stroke survivors from the hospital has an impact on the QOL of the patients and their caregivers.29

The joint family arrangement ensures that each family member contributes to caregiving, but in case of nuclear family, stroke survivor had to suffer careless hours alone because of job concern of caregiver, particularly if patient's spouse is no more. Although having enough evidence of financial support and assistance in daily living, this study failed to generate evidence in relation to emotional support. Numerous studies have emphasized the importance of social support in achieving a high QOL. The first theme mentioned by the patients in a qualitative study conducted by Lynch et al was social support.30 King et al, through their study about QOL after stroke in 86 stroke survivors, reported that the only variable that was a predictor of overall QOL and QOL for each domain was social support.23

India's health care model does not have any arrangement for follow-up of stroke survivors postdischarge at the community level. Hence, there is an urgent need to track the stroke survivors in the community to offer them appropriate rehabilitative services. Primary care physicians can assume a significant role by not only looking after tracking of stroke survivors along with providing rehabilitative services but also creating awareness at the community level about stroke and its associated risk factors by carrying out various information, education, and communication (IEC) activities in the community.

Provision of education, training of caregivers in necessary skills, self-management programs, and active participation of caregivers are interventions which are paramount to improve the QOL of stroke survivors as well as caregivers. Periodic meetings between survivors, caregivers, and primary care physicians would help the stroke survivors and caregivers to communicate and share their feelings and issues, and discover amicable solutions to their day-to-day issues.31

The therapeutic outcome in stroke, to date, is considered by mortality aversion and survival during immediate poststroke period at border level. The QOL enjoyed by poststroke survivors and reversion extent of functionality is still a rather gray zone while formulating policies in National Program for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS). Our study reveals a hidden yet essential requirement to pay attention to poststroke survivor life quality, as the poststroke disabilities are lifelong and have the potential to adversely affect not only at individual plane but also at family and community echelon.

Conclusion

Stroke has a considerably negative impact on the QOL of patients and their caregivers. This calls for interventions targeted at both stroke survivors and caregivers to improve their QOL. Caregivers should be sensitized with proper counseling and training through health care institutions to ensure appropriate care and management of stroke survivors at home, as it will also help in addressing their psychosocial needs, and minimizing the knowledge gap, doubts and uncertainties about the disease and its aftereffects.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding None.

References

- Update on the global burden of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke in 1990–2013: The GBD 2013 Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;45(3):161-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- The changing patterns of cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors in the states of India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2016. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(12):e1339-e1351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke epidemiology and stroke care services in India. J Stroke. 2013;15(3):128-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Employment status, social function decline and caregiver burden among stroke survivors. A South Indian study. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:97-101. (1-2):

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden Faced by Caregivers of Stroke Patients Who Attend Rural-based Medical Teaching Hospital in Western India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2020;23(1):38-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of depression, social activity, and family stress on functional outcome after stroke. Stroke. 1993;24(10):1478-1483.

- [Google Scholar]

- Problems and benefits reported by stroke family caregivers: results from a prospective epidemiological study. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2129-2133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the efficacy of different upper limb hemiparesis interventions on improving health-related quality of life in stroke patients: a systematic review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013;20(2):171-188.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and functional status after carotid revascularisation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(6):634-645.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life after surgical decompression for a space-occupying middle cerebral artery infarct: A cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2015;15:156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life after stroke: impact of clinical and sociodemographic factors. Clinics (São Paulo). 2018;73:e418.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of life satisfaction within couples one year after a partner's stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(3):219-224.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life of post-stroke patients and their caregivers. J Med Life. 2010;3(3):216-220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting burden on caregivers of stroke survivors: population-based study in Mumbai (India) Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15(2):113-119.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative study exploring patients' and carers' experiences of Early Supported Discharge services after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(8):750-757.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measurement of quality of life in stroke patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2006;42(9):709-716.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114-116. (7227):

- [Google Scholar]

- The combined impact of dependency on caregivers, disability, and coping strategy on quality of life after ischemic stroke. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Valued activities and informal caregiving in stroke: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(18):2223-2234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and psychological distress of caregivers' of stroke people. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2017;26(4):154-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke family caregivers' support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(4):315-324.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for stroke family caregivers and stroke survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):30-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient with stroke: hospital discharge planning, functionality and quality of life. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017;70(2):415-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative study of quality of life after stroke: the importance of social relationships. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(7):518-523.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trialog-an exercise in communication between consumers, carers and professional mental health workers beyond role stereotypes. Int J Integr Care. 2010;10:e014. (Suppl):

- [Google Scholar]