Translate this page into:

Frontonasal dysplasia (Median cleft face syndrome)

Address for correspondence: Dr. Seema Sharma, Department of Paediatrics, H. No. 23, Type 5, Block B, Dr. Rajendra Prasad Govt. Medical College and Hospital, Kangra (Tanda), Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: seema406@rediffmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

This is a report of a rare case of frontonasal dysplasia (FND) in a full-term girl with birth weight of 2.750 kg. The baby had the classical features of FND. There were no other associated anomalies. There was no history of consanguinity and no family history of similar conditions. So inheritance of this case could be considered sporadic. Maxillofacial surgery should be considered for all patients for whom improvement is possible. However, in developing countries where there are considerable limitations in provision of social services, with economic and educational constraints, correction of such major defects remains a challenging task.

Keywords

Facial cleft

frontonasal dysplasia

hypertelorism

Introduction

Frontonasal dysplasia (FND) is also known as Burian's syndrome or median cleft face syndrome.[1] First recognized in the mid-nineteenth century,[1] it is a rare condition and only about 100 cases have been reported worldwide till 1996.[1–3] This condition is usually sporadic, but a few familial cases have been reported.[4–7]

Case Report

A female neonate second in order of two, born out of non-consanguineous marriage with no family history of FND was born by LSCS. Antenatal period was uneventful. On examination she was found to have widow's peak, anterior cranium bifidum occultum; true ocular hypertelorism; broadening of the nasal root; median cleft nose; and a median facial cleft affecting the upper lip and palate. There was left-sided microphthalmia [Figure 1]. Head radiographs showed macrocephaly and brachycephaly with dysmorphic face. Rest infantogram was normal. Ultrasound examination of the brain revealed absence of corpus callosum. No other congenital anomaly was seen on gross examination. Owing to inability to do postmortem we were unable to look for detailed structural anomalies of central nervous system. Baby required resuscitation after birth and shifted to nursery. Genetic counseling, appropriate treatment and prognosis were explained in detail to the parents but they decided to give consent for do not resuscitate (DNR). Baby died at 36 hours of life.

- Anterior cranium bifidum occultum

Discussion

In 1967, De Meyer first described the malformation complex ‘median cleft face syndrome’ to emphasize the key mid-face defects. Since then several terms have been introduced: Frontonasal dysplasia, frontonasal syndrome, frontonasal dysostosis, and craniofrontonasal dysplasia.

FND is a rare developmental defect of craniofacial region where midface does not develop normally. The exact cause of FND is not known. Several genes have been identified which exert effects early in embryogenesis resulting in malformation of a specific structure. In midline craniofacial development, most important involved genes are the SHH, TGIF, GLI2, TBX22, ZIC2, SIX3, TDGF1. TGIF mutations affect brain development resulting in different patterns of cerebral and facial manifestations. However, molecular studies are required to prove this hypothesis.[8]

The exclusively sporadic occurrence of FND is indicative of unlikely hereditary pathomechanism. However, in families with an affected child, generally malformations tend to occur a little more frequently.[7] This dysmorphic syndrome is polygenetic, because it is sometimes inherited as a dominant and sometimes as a recessive trait.[1] The parents of an affected child can expect the risk to be 25% for the next child.[179]

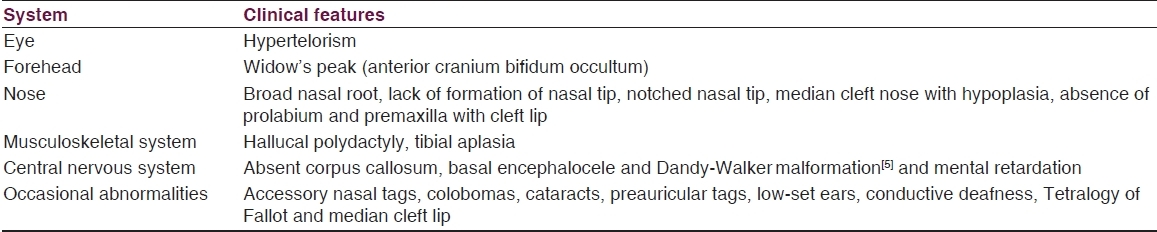

The embryological origin of this syndrome is in the period prior to the 28-mm crown-rump length stage. During the third week of gestation two areas of thickened ectoderm, the olfactory areas, appear immediately under the forebrain in the anterior wall of the stomodeum, one on either side of a region termed the frontonasal prominence. By the up-growth of the surrounding parts these areas are converted into pits, the olfactory pits, which indent the frontonasal prominence and divide it into a medial and two lateral nasal processes. FND is due to deficient remodelling of the nasal capsule, which causes the future fronto-naso-ethmoidal complex to freeze in the fetal form. Experiments show that a reduction in the number of migrating neural crest cells results in these multiple defects. The depth and width of the vertical groove may vary greatly.[10] Clinical features are variable according to severity of expression [Table 1]. The important differential diagnosis of FND includes frontofacionasal dysplasia (FFND), which has ocular defects and midface hypoplasia in addition to the midline facial cleft.[11–14] Acro-frontofacionasal dysostosis is another disorder, which is distinguished from FND by the presence of campto-brachy-polysyndactyly and limb hypoplasia[6]. Craniofrontonasal dysplasia is characterized by the presence of coronal synostosis,[7] as opposed to a bifid cranium in FND.[7] Morning glory syndrome is primarily an uncommon isolated optic disc anomaly, but some cranial facial and neurologic associations have been reported.[15]

Prenatal diagnosis is important with ultrasound observation of craniofacial anomalies (holoprosencephaly). At birth presence of two or more of the following symptoms is considered positive for FND: A skin-covered gap in the bones of the forehead (anterior cranium bifidum occultum); hypertelorism; median cleft lip; median cleft nose; and/or any abnormal development of the center (median cleft) of the face. Diagnostic evaluation ranges from a simple x-ray of the skull to genetic characterization. Computed tomography is the standard study for the evaluation of these patients.[16]

Owing to occurrence of high risk (25%) of a similar craniofacial anomaly in the next sibling[1] genetic counseling of the parents is an important part of the management strategies. Cosmetic surgery to correct the facial defects is recommended. In severe cases, additional facial surgeries may be required. These include reformation of the eyelids (canthoplasty), reformation of the orbits (orbitoplasty), surgical positioning of the eyebrows, and rhinoplasty. In FND, early and continuing intervention programs are necessary to assist the affected individual.

In conclusion, individuals diagnosed with frontonasal dysplasia usually are of average intelligence and can expect a normal life span. The affected individual may die shortly after birth if corrective surgery is not performed as soon as possible. Natural history and lifespan depend on severity and complications. Religious factors and social customs prevent detailed postmortem examination to study the various internal malformations. This is a severe handicap in learning and understanding the entire spectrum of embryological and structural defects.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Frontonasal dysplasia with alar clefts in two sisters. Genetic considerations and surgical correction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;57:553-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysplasia and lipoma of the corpus callosum. Eur J Pediatr. 1985;144:66-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysplasia: Analysis of 21 cases and literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:91-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysplasia: Analysis of 21 cases and literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:91-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysostosis in two successive generations. Am J Med Genet. 1999;87:251-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysplasia: Case report and review of the literature. Kinderarztl Prax. 1990;58:415-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The syndrome of frontonasal dysplasia, callosal agenesis, basal encephalocele, and eye anomalies-phenotypic and aetiological considerations. Int J Med Sci. 2009;1:34-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frontonasal dysplasia (FND) with bilateral anophthalmia: A case report with review of literature. Pak J Med Sci. 2005;21:82-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The malformed infant and child-An illustrative guide. Oxford, England: Oxford University; 1983. p. :262.

- Frontofacio nasal dysplasia: Evidence for autosomal recessive inheritence. Am J Med Genet. 1984;19:301-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fronto-facio- nasal dysostosis - A new autosomal syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1981;10:409-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiology of syndromes and metabolic disorders. In: Pediatric Surgery (2nd ed). Chicago, IL: Year Book Medical; 1983. p. :235.

- [Google Scholar]